“Lots of Burials near Playgrounds: There Are Swings and a Row of Crosses.” the Story of a Student Who Spent Three Months in Occupied Izyum

Izyum is a small town in the Kharkiv region, which has been under Russian occupation almost since the beginning of the war. Despite this, all this time the town continues to be shelled. On July 25, the mayor of Izyum Valeriy Marchenko stated that the density of shelling in Izyum is greater than it was in Mariupol at the height of hostilities. Zaborona journalist Polina Vernyhor spoke with Illia Puntusov, a graduate student of one of the Kyiv universities, who spent the first months of the war in his native Izyum. Given below is his story about the beginning of the war, Russian roadblocks, looting, and collaborationism.

War

On February 24, around half past five, I got a call from an acquaintance who lived in Kharkiv at the time. She said that the city was being bombed. That’s how I found out that the war had started. The official statements from the authorities appeared and it became clear that everything was serious.

For the first week, almost nothing happened in the town itself. It was strange because I saw on the news that Kharkiv was being destroyed with fantastic dynamics in the first five days, but nothing was happening outside my window: there were no soldiers, it was not clear how to behave, there were no air raid alerts – nothing at all.

The first air raid on Izyum took place at night on March 28. About a week after that, we were regularly bombed. On March 7, the occupiers issued an ultimatum to the local authorities: either you surrender Kupyansk, or we destroy it. The locals immediately came out with a statement that they would not cooperate with the occupiers. Almost immediately, the authorities packed up and left, leaving some 25,000 people behind.

-

Izyum. Photo courtesy of Illia Puntusov

Many people said that they had left – locals saw convoys of private vehicles: cars, trucks, which were taking away property. All this belonged to the current MPs, the mayor’s team.

At that time, it was still quite realistic to evacuate people from Izyum. However, all that the local authorities did was to provide 2-3 buses that ran for several hours through the central streets of the town and offered residents to leave. There was no information campaign, warnings, or anything really organized. And still not. These buses left Izyum 90% empty.

Russian world

Russian equipment entered the outskirts of Izyum on March 8. I saw them under my windows on March 10th. The town is divided into two parts by the river. By the time the Russians entered the town, the bridges across the river had already been blown up. Therefore, it was not so easy to get to the other bank – we had to bypass the river.

Initially, they stood in the area of the Lyceum #2 and the Holy Transfiguration Cathedral. From there they started shelling the center. Throughout March, that part of the town was regularly bombed — it is completely destroyed.

-

Izyum. Photo courtesy of Illia Puntusov

The occupiers settled in all the concrete structures — schools, kindergartens, some more or less protected sites. They dragged there household appliances from stores.

It so happened that Russian checkpoints were located around me. The nearest positions were 800 meters from my house. This was the school that was hit by HIMARS not so long ago. While I was there, it was struck by missiles exactly three times. They didn’t even take out the affected equipment – they just brought in new people. I don’t know what they were hoping for.

When I was home, I didn’t realize how many Russians there were in the town itself. Then, when we were leaving, it turned out that there were four times more than I imagined.

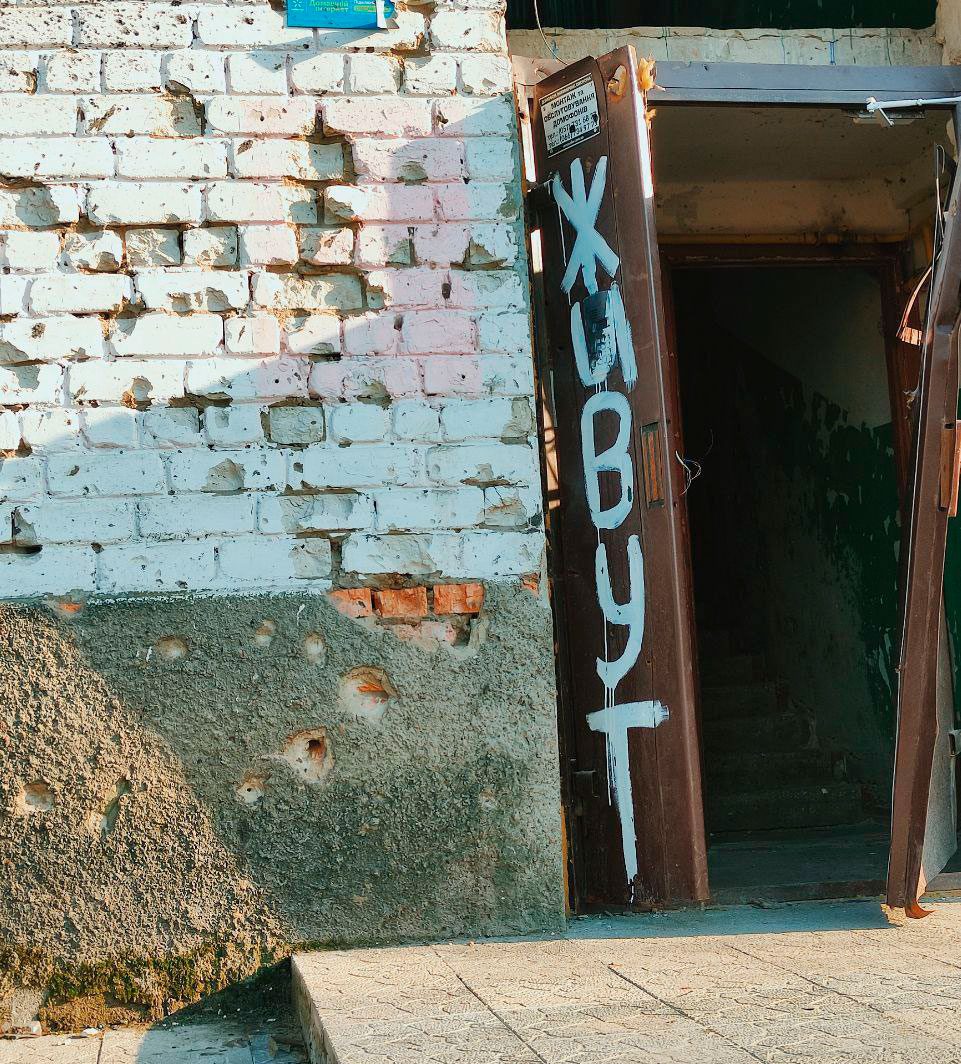

The town under occupation

For the first month, the town was not cleaned at all. They shot some cars, ran them over with armored vehicles — all this remained on the roads. In the central part of the town, I saw many burials right in the courtyards, near the playgrounds: there were swings and a row of crosses. I don’t know how many people died in the fighting while I was there. But this is a significant percentage, it was felt. These are not isolated cases.

-

Izyum. Photo courtesy of Illia Puntusov

The first time I saw a dead person was in the liquor warehouse – it was a guard who was pierced in the head by local marauders. This warehouse was about one and a half kilometers from my house, I went out to scout and saw a murdered man.

Since the beginning of March, there has been no communication or internet in the town. By the third week, we no longer understood what day it was, whether the state of Ukraine even existed, how to behave, and whether it was worth doing anything at all.

I lived with my parents and grandmother in a private house. We had decentralized heating with both gas and solid fuel. Therefore, the lack of electricity, water, gas, and communication was critical for everyone, but in our case, it was a little easier, because we could at least somehow heat the house and cook our food not outside, but inside.

There are no shelters in our area at all. People hid in churches that could accommodate a maximum of 400 people. But 1,300 residents lived in our district.

-

Izyum. Photo courtesy of Illia Puntusov

We didn’t have a basement, because the water table is high in this area, and in principle, no one deepened the buildings there. Therefore, we hid in the corridors from shelling. But in the beginning, they did not hit our district, because the occupiers stood in our area and fired at others.

We started discussing evacuation immediately after the town was bombed. A shell fell a kilometer from our house, it did not explode – it was some kind of luck, probably. Then it was still possible to leave in the direction of Kramatorsk, there were still some bridges. We did not take advantage of this opportunity in time, because we had a big dog and cats. In addition, we did not know whether we would be able to evacuate by train, because men are not a priority there.

In a few days, the bridges in the direction of Kramatorsk were blown up, and we could no longer leave our part of the town on our own. On the northern side, in the direction of Kharkiv, there were already Russian troops – we could not go there either. At that time, there were rumors that civilian cars and buses with people were being shot on the roads. Therefore, our evacuation was delayed.

Roadblocks

Around the twentieth of March, my father and I tried to go outside the district for the first time to familiarize ourselves with the destruction in the town. We came across a roadblock. These were not ordinary soldiers, but some special forces. Their equipment was different, and they behaved differently.

They stopped us about 30 meters before the checkpoint. My father and I approached one at a time. They first checked the documents, then asked the age, whether there is military experience, and whether there are tattoos. They could pay attention to piercing, length or color of hair, clothes, place of registration, the profession you are studying for – all this happened at every checkpoint.

I have large tattoos with Scandinavian motifs on my right arm – a DNR soldier associated it with far-right activities. I have a piercing in my eyebrow – he said that “the Vikings didn’t pierce their eyebrows, only their ears.” This was supplemented by the question “Do you want to go to Valhalla?”. Some occupiers explained the tattoos as Old Slavic mythology, others asked to decipher what was depicted there.

-

Izyum. Photo courtesy of Illia Puntusov

I immediately understood on some intuitive level that if you answer them in one word and your answer does not prompt a further question, then they exhaust themselves very quickly and cannot continue the conversation in the way they would like. For everyone who tried to flirt with them in some way, to play the game they offer, the questioning dragged on for a long time. The consequences are different: I know an example when men with inscriptions on their bodies in Ukrainian were taken to the basement. If anyone had any kind of patriotic tattoo, those people were never seen again. I will not say that there were many such people. But I know about such cases.

Life under the regime

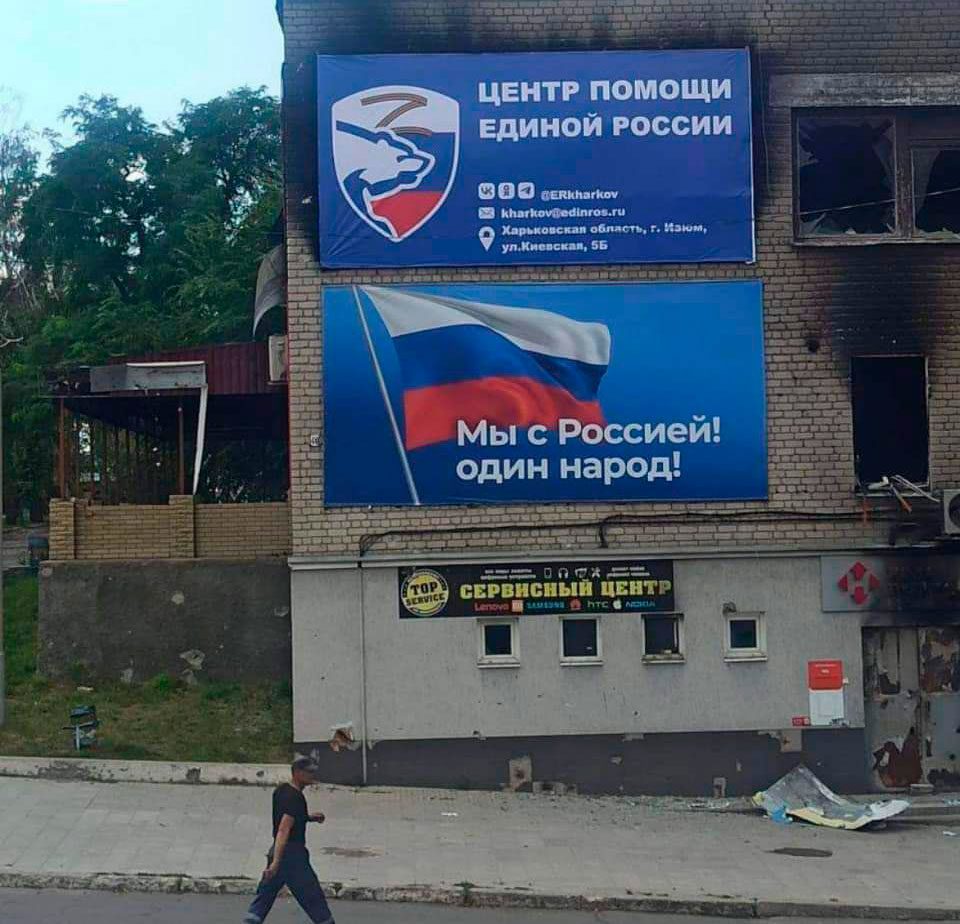

During the first month of the war, not a single humanitarian aid came into the town, not even food for sale. Somewhere in early April, the first aid packages began to appear, unfortunately only from Russia.

-

Izyum. Photo courtesy of Illia Puntusov

We had a large supply of products, which helped a lot. Cold temperatures in the yard helped preserve a lot of food. Most of the population had no supplies, most lived in basements because their houses were shelled. They went and collected food in shops and abandoned apartments. There was no heating, gas, or electricity either.

For the first month, the locals tried not to interact with the occupiers. Then, unfortunately, they started. People began to give them stocks of alcohol in exchange for some rations. The locals looted heavily: they robbed shops and warehouses. At first, the invaders tried to stop and control the looting. But after about five days, they themselves joined this: they began to steal everything.

Moods in the town differed significantly depending on age. All people under the age of 35 categorically did not support the occupation regime. They were pro-Ukrainian, expected de-occupation, and did not communicate or cooperate with the occupiers. In the situation with people 40+, the position was almost radically different. They somehow tried to find a common language with the Russians. I used to stand in line for bread and hear conversations like “Well, finally, our guys have arrived. Now we will get Russian passports and live normally.”

-

Izyum. Photo courtesy of Illia Puntusov

Well, in addition, about 45% of the local authorities are representatives of the “Opposition Platform – For Life” political party, who, unfortunately, were elected to the town council. They really had support. But the percentage of such people is not critical enough to talk about general separatist sentiments.

During the whole time, I did not see a single Ukrainian military man. However, I think I had contact with partisans who are active in the town. Periodic skirmishes took place in various districts, and Russian checkpoints were shot from time to time.

Evacuation

We hoped that the hot phase of the war would not last more than two weeks. Then we thought that it will definitely last no more than three. Then it was postponed for Easter, then for the May holidays. Gradually, this hope was fading: we felt that we simply had to leave under any conditions.

At the beginning of May, rockets were regularly falling around us. One neighboring house was completely torn apart, the other two were torn in half. It seemed that there were no people there at the time.

Around April 28-29, we already started preparing the house for departure. We’ve shut down all communications in case anything happens. We poured water out from the heating system, removed all things that can be removed. All valuables were hidden.

On the morning of May 3, things were already packed. We waited for my girlfriend, got into the car, and drove off. The road to the exit from the occupied territories was about 55 kilometers – we drove through Balakliya. There were five of us in the car: me, my girlfriend, father, mother, and grandmother. They also took cats and dogs.

We drove this section of 55 kilometers for 6 hours, probably – there were a lot of roadblocks there. You go out on each one, they examine you. They undressed me, looked at all my belongings, and asked a lot of questions.

There was such a thing that I was asked what I was doing – I answered that I was studying at a graduate school. They don’t know what graduate school is like. They asked why I did not fight. I answered that I was a pacifist. They do not know what pacifism is. They tried to understand how could I even live in the capital if I am from the province. They do not understand that a conditional scholarship in postgraduate studies can be 200 euros. They don’t believe it. When they found out that I was engaged in doing tattoos, they perceived it as a sinful act, saying, “you not only spoil your skin, but also someone else’s.”

-

Izyum. Photo courtesy of Illia Puntusov

At the entrance to Balakliya, cars were not allowed – we were told about this at roadblocks along the entire road. We went there because of the legend that my girlfriend is six months pregnant. Some roadblocks let us through. For some, it was the best excuse — when the military heard that she was pregnant, they gave her a hand and offered her water. Quite an atypical reaction, I did not expect this.

At the entrance to the city itself, we were told “No”. There was no reason for us to enter. The reason can be either your registration in the city or if someone with such registration meets you. My girlfriend lived in the basement with a man who was registered in Balakliya. She knew his details and said we were going to see him. No one knew where this street was, what kind of person this was. No one knew how to get to it either. The occupiers got into the car and took our documents. We drove in our car, they accompanied us behind. We started to stop and ask the locals. Some didn’t know where it was, some answered that it was in one part of the city, and some said that it is in another. So we drove with them until they said it couldn’t last all day.

We returned to the checkpoint. They talked with us for some time, because they realized that everything we said about this man is a lie, and we started to differ in our answers. It seemed to be the end. At best, we will be sent home. But about half an hour later, they simply gave us the documents and allowed us to go without stopping within the city limits.

In the city itself, at the checkpoints, they didn’t even look at what we had in the trunk. Just checked the documents with the passengers and that’s it. The exit was also almost without inspection. Only they said: “You are going in one direction, no one will let you back.”

So we arrived in Pervomaiskyi. We stayed there, spent the night, ate, and took a shower. We were told what was going on, we received fuel. And the next day we reached Kyiv.

-

Izyum. Photo courtesy of Illia Puntusov

Izyum today

Now we periodically call my friends who stayed in Izyum. There is still no connection in the town itself. Therefore, they have to drive 25–30 kilometers from Izyum to call. That is, only they can call.

They said that the situation in the town began to change a little. For a while, there was some lull. And now the Armed Forces of Ukraine began to actively attack Russian positions. There is information that the headquarters of the 20th Combined Arms Army was withdrawn from the town. They say that the number of personnel, morale and spirit have fallen significantly. They look tired and unmotivated. I think this means that they do not actively interact, do not put pressure on the locals.

About 5,000 to 7,000 residents remain in the town. Most left in the first month. Currently, humanitarian aid is given only to socially vulnerable sections of the population. But it is even difficult to call it humanitarian aid: a can of stew, a can of pate or canned fish, a kilogram of cereal. This is per person per week. Those who are not given assistance need to go to work. There is only one job: go and remove the debris. They are paid for it with some kind of food.

-

Izyum. Photo courtesy of Illia Puntusov

People don’t have cash, and you can’t pay with cards. They introduced an exchange rate of 1 hryvnia to 1 ruble. To somehow withdraw cash from ATMs, you have to go to Svatovo [a town in the Luhansk region, which is temporarily under the occupation of the LNR]. There, the withdrawal fee is from 15 to 30% of the amount.

Izyum is almost destroyed. I don’t know how people will live there in winter. A few days ago, I was informed that some people from the nearest village had settled in our house. They no longer have a home, so they were moved into ours.

Dream

I sent my mother, grandmother, and girlfriend abroad. I don’t want them to go through what they had to go through again. Their moral condition is much worse than mine. The first time we went to the supermarket, my girlfriend had a tantrum because she saw bread on the shelves. She is still calming down, putting herself in order.

My father and I are now in Kyiv. There is no strong desire to return to our house, even after de-occupation. I understand that I have many rather unpleasant memories. My biggest dream is for the existence of the Russian Federation as a subject to cease and the borders of Ukraine to return to the state of 1991.