For 85 days, the Azov steel facility in Mariupol was a shelter for several thousand local residents, a headquarters for the military, a hospital for the wounded, and a fortress that resisted the occupation of the city until the last. The factory was actively bombarded by infantry, fighter jets, and ship rocket launchers. At the end of April, it was possible to evacuate the first civilians from the territory of Azov Steel, and on May 20, the last defenders of the city left. Most of them are still in captivity in the Russian Federation. But Oleh Klochkivskyi was lucky to return. The 53-year-old marksman of the Territorial Defense of Mariupol was one of the last to leave Azov Steel and went through captivity and several exchange attempts. Journalist Polina Vernyhor spoke with the soldier for two days about his military experience. Zaborona publishes an abridged version of his monologue.

War

I was born in Irpin and moved with my parents to Mariupol as a child. All my life I worked at the Mariupol Illich Iron & Steel Works. I spent the last year before the full-scale invasion in retirement. I have a wife, an 11-year-old son, an adult daughter, and my own house. We built it for a very long time, all the money was invested in it. For about 15 years, my wife and I did not go anywhere for vacation, because we were constantly improving something in the house. We lived on the left bank of the city, in the Novoberezhny district. The neighboring Skhidnyi district was shelled by the Russians back in 2015.

I don’t really remember how exactly I found out about the beginning of the war. Probably one of my relatives told me. On the morning of February 24, I turned on the news and saw that almost all of Ukraine was being bombed.

I believed that something would happen. Everything went to that. When, on February 23, the Russians started moving equipment to Donbas, I already understood: this is where it begins. But I was sure that the war would take place only in Donbas, around Mariupol, Volnovakha — all this former ATO line. I could not imagine that they would go to Kyiv, to Kherson from Crimea, to Odesa.

At that time, I did not think about taking my family out, because, again, I did not expect that there would be fighting in our city. All these years we have been assured that this line is protected, that there is anti-aircraft defense. Around noon I began to realize the scale of what was happening. I decided to go to the Territorial Defense.

I called my brother Andrii — he is two years younger than me. We agreed to go to the Territorial Defense headquarters. There were few people at the entrance — some came on their own, and some were drafted. We were enrolled in the 107th battalion of the 109th separate brigade of Mariupol Territorial Defense.

-

Burnt cars after Russian shelling near a church in the city of Mariupol, February 25, 2015. Photo: GENYA SAVILOV / AFP via Getty Images

Get ready to battle. With no combat experience

The next day we took the oath. I counted — there were about 300 of us, although there should have been almost 500. I knew that there were a lot of Russian supporters in the city, but I still thought that among the 400,000 population, enough people would gather to defend Mariupol.

On the same day, we were given weapons, put on buses, and taken to Mariupol State University — we spent the night there. In the morning, the place from where we were taken was shelled — one of the locals reported that he saw military men there.

It turned out that the command of the company were civilians. Some of them never took up arms. They were appointed only because they had a military faculty at the university. We were not instructed, we were not explained what to do, or how to fight. I approached the guys from the intelligence unit — it turned out that some of them had already been in the ATO. I asked how to behave in battle. They started telling me. The other guys also leaned in to listen.

On the morning of February 26, we were quickly gathered, loaded into cars, and taken to different points. Our platoon was taken to school No. 63 in the Western microdistrict. We stayed there for two days and were transferred further along the Volodar highway — this is already the exit from the city. We were the third echelon of defense, the National Guard and the Armed Forces were before us.

We were ordered to dig trenches near the road. We often sat in those trenches. Mines and shells were exploding nearby — it was my ‘baptism of fire’. On the second day of shelling, we came to the commander and quite aggressively explained that we did not want to sit in the trenches — this is illogical, we can be seen from the sky, we have to hide in a nearby building. He agreed.

Once I asked a colleague who fought in the ATO how to stop being afraid. He said, “Don’t worry. When you get into battle, you won’t even be afraid. Everything happens automatically. The fear will come when the fight is over. Then it will be scary.” So it happened later.

Active offensive

We had very few weapons — only machine guns and grenades. The enemy’s armament was much better. So, in the first battle, many of our people died, and many were wounded.

At first, there were mortar attacks — it’s scary in the trench, you can do nothing, you just pray that it doesn’t hit you. And in battle, something depends on you: what position you will take, how you will run over, hide. You can answer, try to kill. There was no fear. The brain seems to be shutting down. When the fight ended, I started shaking. Maybe because I began to turn on my brain and realize what had happened.

Later, we decided to leave, because we were already almost surrounded. We had to restrain the occupiers so that they did not enter the city, and they passed by another road and actually ended up behind us. That’s why we went in the direction of Novoselivka — that is, in the direction of Azov Steel.

The command reported: if someone falls behind the group in battle and has to leave alone, the meeting place is Azov Steel. There was the headquarters of our brigade, the command.

It turned out that when we started to break through there, we were cut off by tanks. There is such a wide road there — Budivelnykiv Avenue. There were two tanks on one side. We tried to pass from the other side, but the locals told us that enemy equipment was stationed there as well.

-

A man with a bicycle in the center of Mariupol, April 12, 2022 NOTE: The photo was taken during a trip organized by the Russian military. Photo: ALEXANDER NEMENOV / AFP via Getty Images

Retreat

We decided to go in small groups. My brother and I were accompanied by six other guys. My mother lives nearby, I know the area well. I suggested a way, and everyone agreed.

A car with men in their thirties drove past us. It seemed to me that it was the Russians who were riding around the district in civilian clothes, spying out on everything. We walked some distance, and the mines began to fly towards where we were supposed to go.

The city was completely destroyed, some neighborhoods were razed to the ground. At first, I thought they were accidentally hitting residential buildings. There are no soldiers there at all. We, soldiers, stand in front, and they hit the back. Then we simply understood that the goal was to hit the city, peaceful residents, houses. It was a strange thing for me — why did they do that? What does it give them? They just had to destroy everything and everyone.

We waited for the shelling to end. We reached the river, bypassed enemy equipment. I went to see my mother on the way — she did not know that I had gone to fight. At first, she didn’t even recognize me, and then she started crying. I had food with me in my backpack, I left everything for her. We said goodbye and I left.

I returned to the guys — my brother was gone. It turned out that he went looking for me. It so happened that he also ran to our mother to say goodbye, but he was going the other way. He was not waited for very long.

We went over the river to Azov Steel. On the way, we saw people dragging drinks and food from warehouses. We hadn’t eaten anything since morning, so we decided to go in and get something for ourselves. There were cookies and non-alcoholic beer. We sat down in the cemetery and ate. Never thought cookies with non-alcoholic beer could taste so good.

On the approach to the facility, someone decided to go right to Azov Steel, and someone, including me, was in favor of going to the left bank, where my family lived. We went in different directions, my brother went to Azov Steel.

-

A view of Mariupol and the Azov Steel metallurgical facility on May 10, 2022. Photo: STRINGER / AFP via Getty Images

The road to the fortress

Soon, mines started flying towards us. Two were wounded, I bandaged them, caught a ride, and sent them to the hospital. I was left alone. Later, I came to the idea that it was not worth going home — there might be already Muscovites there. So I decided to go back to Azov Steel.

Next, I ran a little. Mines began to fly again. Sometimes I fell, sometimes I hid behind trees, behind garages. I ran to Azov Steel. There I met two guys from our battalion. I asked how to get inside because it was already late and the passageway was closed. I was told there was a hole in the fence to climb through. We were afraid that now it would be completely dark, and in the dark, no one would be able to understand who was walking. They can simply open fire without warning. We tried to quickly slip through and get at least to one of our guys, while there was still light. We succeeded.

We were met by the military. They didn’t understand how we got inside. We talked about the hole in the fence. Then we were asked who we are and where we are from. They contacted our headquarters, sent a car for us, and took us to another building. I met my brother there. It turned out that they calmly reached another passageway.

Checkpoint and torture with songs

There was a bridge near Azov Steel, and at the other end of the bridge there was a checkpoint — we were sent there to be on duty for two days. Once we went on duty through the passageway, and when we returned the next day — it was March 14 — the passageway was completely bombed. I think the Russians had to block these passageways because there were Azov tanks on the territory of the facility, which simply could not leave through the ruins.

At the checkpoint, it was necessary to check the documents of those passing by. At first, we tried to do it, but there was a constant stream of people and cars, and Grads were constantly firing. It was very difficult to guess where exactly they are going to bomb next time. There were situations when we were fired upon at the checkpoint. A car drives up, a short-barreled machine gun sticks out, and they start shooting at us. Then they drive away. By the time we get to that intersection to shoot them in pursuit, they are already disappearing.

At the end of March, our group together with Azov was sent to the left bank of the city, where the fighting was going on. We were divided into smaller groups — my brother and I were accompanied by an Azov military man and a border guard. We were on the second line, but at any moment it could become the first. We were there for about 11 days. At exactly five in the morning, the Russians turned on the song “Do Russians want wars?” on the megaphone, turned it off halfway through, and shouted into the megaphone something like: “Ukrainian soldier, surrender, you are guaranteed warm clothes, hot tea, and life.” I saw the same scene in some Soviet war films, when the Germans, word for word, called on the Soviet soldiers to surrender through a megaphone. We looked at each other and said: “Well, what the fuck, don’t they see the parallels with the fascists during the Second World War?”.

It first song was over, they turned on the song “The Russians are coming” and started the mortar attack. The last five days were the most difficult because we had no more shells left, we almost did not respond to them.

The road where we were was full of holes, the houses were broken. When we started digging trenches in these positions, civilians living in nearby houses tried to protest. They said that our positions put their houses at risk: they say that if the Russians see that we are sitting here in the trenches, they will start bombing and hit the houses. We explained that we are not asking for permission: we need to stop the offensive. We quarreled for about three days. As a result, they seem to have realized that we are not hiding behind their backs but protecting them. Sometimes they even brought us some food.

But later the houses were shelled, and everything burned down. People fled, and they were covered by mortar shelling. They were trying to take a very old woman with them — she was probably 90 years old. She could not walk. At first, she was dragged in a wheelchair, then a walker was brought. We wanted to help, but it was impossible — mines were flying everywhere. A few minutes later, I looked out of the trench to see them — and this woman was already lying dead.

-

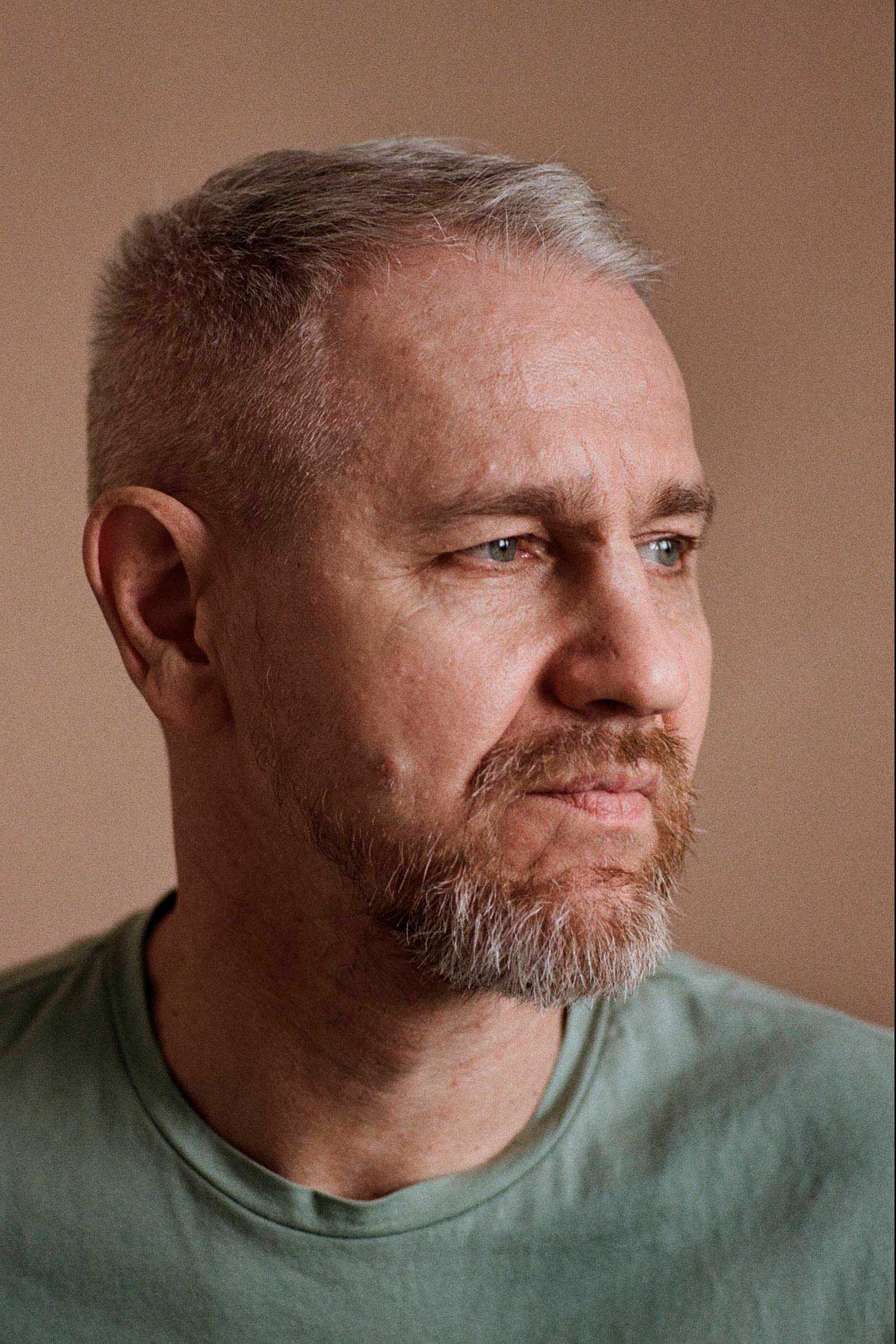

Oleh Klochkivskyi. Photo: Vasylyna Vrublevska / Zaborona -

Oleh Klochkivskyi. Photo: Vasylyna Vrublevska / Zaborona

Death

The 8th of April was the scariest day of my life. The shelling did not stop that day. At any minute, we expected that there might be an attack on our positions. During the shelling, my brother and I constantly talked to each other to make sure we were alive. And when the mine exploded, I shouted: “Andrii, everything is fine!”. The answer was silence.

I climbed out of the trench. I looked at the other side of the road, where my brother was. His head was sticking out of the trench. A fragment was sticking out of his head from both sides, and something white was leaking out.

I shouted to the commander: “Andrii is cargo 200!” I don’t know why I chose this wording. Probably, at that time, we all became emotionless and dry. Now I remember, and a lump is coming to my throat. And then, it was as if I heard myself from outside, and I was horrified that this did not cause the emotions. Like a person who sees a murdered brother usually feels.

I picked up Andrii; he was still alive — snoring and moaning. We pulled him out, called an evacuation vehicle, put him in a car, and returned to the trench. I hardly thought about my brother. I hoped everything was fine, but others said he had no chance.

Hell of a pain

As usual, we had to put a guard on duty in the evening. Four of us, one at a time, stood in for at least some rest. Our friend stepped in — it was about eight in the evening, and it was already dark outside. Later, he came running covered in blood. Some local came up from behind and wanted to thrust a knife into his neck, but was drunk, missed, and hit him in the shoulder.

We slept 2-3 hours a day at that time. There was great tension, shelling everywhere. I was on duty, I wanted to sleep. I did not notice how I fell asleep — for a moment, or maybe 10-15 minutes. But I was terrified: if I fell asleep again, they could kill me here, at the post, and the guys won’t even know. That’s why I went to change with someone. There was an unfinished two-story building near the checkpoint, so we rested there. Another military man went to the post instead of me. I sat down, had a snack, and decided to sleep for at least an hour and a half. I fell onto the bed and instantly passed out.

I woke up as suddenly as I had fallen asleep. A hit. And behind it – a hellish pain in the left leg, all the way from the thigh. I don’t remember if I screamed, but I remember that this pain filled me completely. I opened my eyes — everything was in the dust, and I found myself under the rubble. I only heard how the mines continued to fall and burst nearby.

It seemed like I would pass out now, either from the pain or the loss of blood. I was afraid that they wouldn’t find me if I were unconscious. I somehow got out and started screaming. He looked down for a moment — the leg was dangling as if it was hanging on the skin. I understood I would not get out on my own, so I shouted loudly and called for help. The boys heard me, carried me out, put me in an evacuation vehicle, and our commander was already there, also with an injury.

Hospital

They took us to “Azov Steel,” to the passage. Near the central gate was a point where the wounded were treated and taken to the factory, where there was a hospital. There was a separate room where people performed operations, and I was immediately taken to the operating table. I was stitched up and sent to the bunks where the other wounded lay.

In a large room, two rows of overbed tables are next to the wall. There were seriously injured people who could not move. I was put there first. For the first five days, antibiotics were injected to prevent inflammation. In other rows lay those who could hold on for a while, walk on crutches. And even further, there were beds on 2-3 tiers — the wounded who could walk were already lying there.

Once every few days, helicopters flew in, bringing weapons and medicines and taking away the wounded. Doctors decided who to take away. Only military personnel was in this bunker [where the wounded were kept]. One of the civilians was a four-year-old girl, the daughter of a nurse. There was no one to leave her with, so her mother took her to a military bunker. When there was an evacuation [under the watch of occupiers], the two tried to be taken out as civilians, but occupiers found out who her mother was and took this nurse as a prisoner. The girl and civilians were sent by bus to Zaporizhzhya.

When I could speak, I immediately began to find out whether my wounded brother was there. We looked through all the lists, but he was nowhere. There were other hospitals in Azov Steel, but it was the only place where seriously injured people were brought. I hoped he would be sent by helicopter to the territory controlled by Ukraine. But he should still be on the lists of fighters. But he was nowhere.

-

A wounded Ukrainian military man at the Azov Steel metallurgical factory in Mariupol, May 10, 2022. Photo: DMYTRO ‘OREST’ KOZATSKYI / AFP via Getty Images

The last bastion

On April 21, they tried to exchange us for the first time. Even the Red Cross came. But everything was canceled. Some civilians were taken out, but they did not want to let us go. As I understood, the Russians were against it: they demanded to take us as prisoners despite everything.

There were several such attempts to evacuate us from Azov Steel. It lasted until May 16, when the first [military] began to be withdrawn. It became clear that they took us as prisoners, and they would exchange us only after that.

After that, an entirely accurate shelling of Azov Steel began. First, in the kitchen — no one died, but the kitchen was wholly destroyed. We had much less food because most supplies ended up under the rubble. Then our people brought food from other bunkers. We ate once a day: wheat porridge, less than half of a 200-milliliter plastic cup, and a piece of lard.

Then a bomb came from the other side and hit the edge of the building at the same point. Two people were buried alive. A huge hole appeared in that place, where the sky was visible. People in the bunker hung it with blankets — drones were flying above, and they could see that the military was inside.

A few days later, the missile struck again, killing two more. The bodies began to decompose; in the closed space, the stench seeped into every object. It was impossible to breathe — we took masks and wet them with water. That’s how we lived.

The last few days have been tough with the medicine. There were no painkillers. Even operations were performed without anesthesia. In some cases, people died from pain — the heart could not take it. Once, they put a guy next to me, head to head. He moaned in pain but stopped in the middle of the night. I thought he was tired and fell asleep, but he didn’t move. I leaned over to the guy to check his breath, and he smelled like a dead person.

Exit

In May, we were informed that on the 16th, we would be taken out of Azov Steel. We were skeptical at first because there were many attempts and all failed. But, to our surprise, they began carrying out the most seriously wounded this time. The next day they were taking out the second batch, I had already gotten there. They took me outside; I looked at “Azov Steel” — and there were solid ruins, skeletons of birds killed by explosions. I saw the sun for the first time in a month and a half, and the sky was so blue and beautiful. I sat and just couldn’t look away.

Someone carried me to the emergency room, then to the emergency room. Those who could walk were put on buses. They stood there for several hours while checking. Then they took us to Novoazovsk. And the ones who could walk — immediately to Olenivka. In Novoazovsk, they gave me crutches, and I slowly started walking.

-

Evacuation of the Ukrainian military from the Azov Steel metallurgical facility, May 17, 2022. NOTE: Screenshot from a video released by the Russian Ministry of Defense. Photo: Russian Defense Ministry / Handout / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Novoazovsk

We were searched in the hospital. We left “Azov Steel” with some personal belongings — they told us that we could have phones and some valuables. The only thing was that no weapons, sharp or cutting objects were allowed. I took the phone, cleaned it before, and threw away the sim card. There was still a mug I wanted to keep. I put it in a bag. But everything was taken away in the hospital.

They divided us into wards, and a person with a weapon was on duty near each one. It was forbidden to go out. They searched us again and again. They even took away belts and shoelaces — so we could not do anything with ourselves.

They fed us three times a day. The food is like in a regular hospital. I won’t say that it was very tasty, but [after the “Azov Steel” ration] that food was a feast. If you want to go to the toilet, you must first ask. A man with a machine gun was there, and he forbade closing the door to the booth — he just stood there and watched all the time.

We were interrogated by the citizens of DNR and the Russian investigators. But they were such a mess that I had diarrhea after the detailed interrogation. They asked who I was, where I was born, and whether I fought until February 24. And then, the investigator got distracted and asked me to go away. Then they entered the ward and asked who had not been questioned yet. I didn’t confess.

We were in Novoazovsk for a day and a half. Then we were transferred to Donetsk, to the 15th hospital. Their wounded were also lying there. They also guarded us there. When they took us to some examination as a group, there were as many guards as there were us. But there was much less security on the floors than in Novoazovsk. I understood that they were not so much guarding us so that we wouldn’t run away but from their soldiers who were lying in this hospital. There were many scumbags, and they were outraged that we were being treated; they said soldiers should shoot us.

Interrogation

In Donetsk, they interrogated us again. They asked about the details of the hostilities, in which bunker I was lying. Of course, I had to answer everything honestly — they had a lot of information, and it was scary that they could do something to me if they caught me lying. People from the DPR came in masks, and the Russians just like that, one even came in civilian clothes.

A Russian man from the FSS interrogated me. He began to ask where I was injured. I tell, and he clarifies: “It’s such a gray building over there, right?”. I was surprised he knew such details and asked if he was from Mariupol. He smiled and said no. During the interrogation, I realized that he was there after the battles and knew everything there.

I remembered that a couple of weeks before the full-scale invasion, a bunch of new people had appeared in the city. My wife noticed it too. It was clear from them that these were not local people: their behavior, manner of communicating, their clothes — everything was different. Once, my wife and I were passing by the headquarters of “Azov” on a bus, and three non-locals were sitting next to us. One pointed his finger in the direction of this headquarters, and the other replied: “Wait, wait, they don’t have long left.” Maybe under different circumstances, we would have called the police. But we have quite a lot of people with pro-Russian views in our city, and they don’t arrest them for that.

We naively believed that Mariupol was thickets. There are areas where you can get lost. They thought they could not take Mariupol because they would simply get lost. But, it turned out, they already knew everything. They had already gone around these thickets themselves, checked, looked. They had a detailed plan of the city.

Hope

We waited a long time for the exchange. The first time, the Russians woke us up on June 13 at four in the morning and told us to [pack] our things for departure. They took us three hundred meters away from this hospital. We stayed there for an hour, and everything was canceled; they took us back. They told us that Ukraine did not want to take us away and that no one needed us. But I understood that the reason, most likely, was that there were no Azovs among us.

In two weeks, they woke us up again in the morning, but this time nothing happened. In a few days, they went around the wards, checked the lists, and made some marks. We understood that a new exchange was being prepared. On June 29, I woke up very early — it wasn’t even four o’clock yet. The guard shouted for everyone to get up and line up in the corridor. I was very happy. We sat in the corridor for an hour, and then we were again put on buses and taken somewhere. We waited again for a long time until suddenly we drove in the direction of the exit from the city. They took us to Berdyansk and then to Vasylivka; there was an exchange near it.

All of ours were on crutches, stretchers – all wounded, and some on their own feet. We were put in the carriages of the “express” and taken to Zaporizhzhya. There they brought it to the distribution point. Volunteers started running between us, handing out cigarettes — Azov Steel had problems with this. I took it and smoked it for the first time since February 24. It was a great pleasure.

Treatment

We were distributed among hospitals, fed with delicious food. Everyone was happy, smiling. Then volunteers came and brought many goodies and clothes. They came almost every day. I was examined in the hospital. It turned out that I had a broken femoral neck and an open fracture. It is necessary to put endoprosthesis. I refused because I thought the operation should be done in Kyiv or to go to Germany, to my family.

Later, I was sent to the Mechnikov hospital in Dnipro. There they stated that some virus got into the wound — it is not surprising, considering the conditions in which I was stitched up at Azov Steel. We must first cure this virus and then do the operation.

I stayed in Mechnikov for three weeks, then was transported to Kyiv on an evacuation train. First, I got into “Feofania.” At that moment, my legs were very swollen, and I had to drill holes in the bone. Dirty blood came out of me for several days, but my leg stopped swelling. In two days, I was transferred to a military hospital — it turned out that one hospital could not keep one patient longer than three weeks, so we were constantly moved.

-

Rehabilitation ward for Ukrainian military personnel in a hospital in Dnipro. Photo: Alex Chan Tsz Yuk / SOPA Images / LightRocket via Getty Images

I can’t do operations until October — the wound needs to heal. The bone has grown incorrectly, so it is difficult for me to step on my leg — I cannot stand without crutches. I think I will do the operation in Ukraine because you have to collect a lot of documents and wait a long time abroad.

Mine

I didn’t know anything about my family for a long time because I lost contact with Mariupol on the 4th of March. Someone at “Azov Steel” suggested where you can catch the Internet. I gave the numbers of my daughter and wife to the boys who were going there and asked them to contact me. They called my family through messenger. My parents were already in Poland at that time, preparing to leave for Germany.

It was as if a stone had been thrown from my soul. Dying was no longer scary because I knew the family was safe. Already when I was exchanged, we managed to talk normally. They left Mariupol on March 18 — until then, they had to starve. When they were leaving, they saw the consequences of the “liberation of Mariupol” the 11-year-old son looked at the murdered townspeople. It hit them all hard, and now psychologists are working with them.

My 75-year-old mother remains in Mariupol. Thank God, they don’t touch her there, they don’t drag her to interrogations. We communicated with her on the messenger. My brother Andrii’s wife and daughter remained in Mariupol. They did not leave because she could not leave her old parents. We also keep in touch with them. They often ask about Andrii, but I only say that he was injured and I am trying to find him now. I don’t say anything to my mother either. I myself still hope that he is alive — we just have to keep looking.

-

Oleh Klochkivskyi. Photo: Vasylyna Vrublevska / Zaborona -

Oleh Klochkivskyi. Photo: Vasylyna Vrublevska / Zaborona

This material is produced within the project «EU Emergency Support 4 Civil Society», implemented by ISAR Ednannia with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of “Zaborona Media” and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.