Canadian photographer Donald Weber consistently works with the themes of human macro-histories woven into the large canvas of historical catastrophes and investigates how they remain in historical and cultural memory. He was one of the first to go to film the accident at Fukushima, visited Chernobyl, and spent weeks walking the beaches of Normandy, looking for the sand on which his grandfather may have walked, who participated in the battle during the famous amphibious operation of the Second World War on this coast. Ivan Chernichkin spoke with Weber about how a motorcycle accident in Africa influenced his desire to take photographs, whether sand has a memory, why he is interested in nuclear disasters, and whether there are deadlines when you can start working with tragic subjects (such as the war in Ukraine).

Donald, tell us how you got into photography.

To understand why I got into photography, you have to understand that I have always been interested in history. I was born in 1973 — I was 12 years old during the Cold War. I have always been fascinated by the imagery of the Cold War and how it was portrayed in the news, newspapers, and movies. “Look, these are the people who are going to nuke you.” My peers in the Soviet Union perceived the Western world in the same way — “the Americans will come for us.”

There was one moment that I remembered very well. I was driving in a car with my dad, it was January or February, and it was very cold. We were driving past a hockey arena, and it said something like, “Welcome the players of the Soviet Union hockey team.” Father leaned over to me, pointed to the sign, and whispered in my ear very quietly — I don’t know why, there were only two of us in the car: “Don, these people don’t even have butter.” After that incident, I started watching photos and news from the Soviet Union.

I turned into a detective looking for evidence that they did have that oil. Then came the fall of the Berlin Wall, Romania, Ceausescu, and finally, the year of 1991 and the collapse of the Soviet Union. These historical events shaped my perception of photography.

-

Donald Weber. Photo: Donald Weber

You graduated from an art academy and then worked as an architect in the Netherlands and Toronto.

When I was about to apply to various art colleges in high school, I went to the school’s photography teacher for advice and asked which college I should apply to, this one or that one. He looked at me and said: “Neither. You suck as a photographer.” I remember that, word for word. It was like a knife to the heart. I put my camera down almost that same day and thought, “Okay, I’m a lousy photographer. I’m just going to apply to art school in Toronto kind of randomly.” I enrolled as an architect, but architecture lacked what I always loved about photography. Photography was a way to try to understand or learn about a thing or event — to explore it. In this sense, the architecture was very dry.

I got my first camera when I was 12-13 years old, and at 18, I was told I was a lousy photographer. But eventually, I returned to photography when I was already in my 20s. After graduating from the academy, I worked in Rotterdam in the studio of Rem Koolhaas [a famous Dutch architect]. A few years later, I returned to Toronto and worked for the firm for three years.

-

From the book Bastard Eden, Our Chernobyl. Photo: Donald Weber -

From the book Bastard Eden, Our Chernobyl. Photo: Donald Weber

-

From the book Bastard Eden, Our Chernobyl. Photo: Donald Weber -

From the book Bastard Eden, Our Chernobyl. Photo: Donald Weber

In the last year of working for this company, I thought I would take a motorcycle and travel around Africa on it. I did so, but I got into an accident — I was hit by a car. And so I fly off the motorcycle, slide down the road, look at the bike, which is smoking and steaming, and say to myself: “Okay! Now is the time. You will be a photographer.” It was a kind of turning point. I enrolled in a one-year photojournalism program at a small college when I returned to Canada. Since then, I have been working as a photographer — it turns out, for 21 years. Wow!

-

From the project Zholtye Vody. Photo: Donald Weber

Can you compare architecture and photography? When studying photojournalism, did you try to forget everything you were taught in art school and build everything from scratch?

For a long time, I tried to eliminate architecture from my life. I din’t like city. I associated it with a very static space. Part of my problem with architecture was that I had to be an architect and not do architectural art. In photography, I’ve always felt the immediacy, the mobility in which you see things develop and change, even when you’re working on one task, let alone an essay or a project. All these layers are like a snowball or a rose, and as it [the project] grows, it becomes clearer.

But architecture has greatly shaped my practice, and I am grateful. These are my constant thoughts about the connection between space and a human and how social this connection is. But I didn’t know that before — it took me over ten years to figure it out. I think my interest in how I maneuver in space is also shaped by architecture.

What prompted you to come and shoot in Ukraine? Can we say that your childhood memories of the Soviet hockey team and your father’s words about butter pushed you to some extent?

I have never been interested in propaganda, but I would say that I am a victim of propaganda. I realize it now, but as a child, I was entirely seduced by it. I think the era I grew up in, the 1980s, with reggae and Star Wars on one side, and rockets, Chernobyl, watching parades on Red Square on the other, all of that shaped the interest: “Let’s… Let’s go [to the USSR] and see where it all happened with your own eyes.” I don’t know if the photography was the exuse to go there or was the reason that I went there was because of photography.

I think I should have probably been a historian and maybe study the cultural history of the Soviet Union. But in a sense, I see photography as a much more subjective history format. And in the end, what I photographed in Russia and Ukraine was a story of a subjective format. History from below, history from the streets. Not being an academic historian or scientist, I simply collect my personal experience of meeting different people and try to turn it into a photograph.

-

From the book Interrogations. Photo: Donald Weber

Your project and book Bastard Eden are devoted to the Chernobyl zone — is this also from childhood memories?

Perhaps part of this comes from the childhood. But I think they [memories] became instigators — like sparks, like a match that ignites a flame. I come from a place full of assumptions, and I’ve always wanted to get rid of any assumptions.

I felt that if I could just move and be mobile through a space and a place, I could get closer to understanding Chernobyl. The other thing that pushed me was that I’ve always felt a little uncomfortable with the way journalism works. It’s all about establishing a narrative — it’s tough to break away from it once a narrative is established, especially in the American media. I am very sensitive to this and have come to feel it because I have been a part of creating these narratives through my work. And, of course, the giant narrative about Chernobyl is that it’s a ghost town where no one lives.

I was in Kyiv — my first trip to Ukraine — and I just decided to go there and see, I’m so close. I visited Ivankiv and a few other small villages nearby and was surprised that everywhere was full of people. The fact that many small towns with an active population around the Zone really surprised me. Because I was more than sure that it was a dead zone, then the Mayor of Ivankov told me about the Chernobyl Riviera. I thought: such a strange clash of terms, and asked him: “What is this?” He replied: “Expensive houses, yachts, rich people.” It’s stuck in my head forever.

The essence of my work in Chernobyl is to understand how the past appears in the present. I can look at historical systems and structures, but I’m more interested in how they manifest themselves today. And if this is a story about older people living in the Zone, I want to know about the young people outside it. So that’s what guided my work process in Chernobyl at the time.

-

From the book Bastard Eden, Our Chernobyl. Photo: Donald Weber

You were one of the first to visit Fukushima after the tsunami. Can you somehow compare what you saw there with what you saw in Chernobyl?

Thanks to my work in Chernobyl, I became interested — this may sound pretentious — in invisible things. In Chernobyl, I was very concerned about the weird paradoxes in which I found myself: the very nature of radiation, the fact that it is invisible, but its material traces are everywhere: the mortality rate, the Red Forest, the economic consequences. So I became interested in how invisible things manifest materially. What I love about photography is that you get to make the image. You take a picture, and wow: whatever is there, it comes out on the surface, on the paper, on the sensor. Therefore, Chernobyl and Fukushima have a lot in common.

-

From the Fukushima project. Photo: Donald Weber

Japanese authorities very quickly closed the area within hours of the accident. I wondered what Chernobyl would look like immediately, within a few days after Pripyat was abandoned. And this was also part of the interest in Fukushima. I remember seeing oranges on the tables and food in Fukushima, clothes from the dry cleaners hanging on the door, and things like that. I also saw something similar in Pripyat but, of course, in an exhausted state.

In Canada, we have nuclear power, and we love nuclear power — oh, it’s so clean, wow! On the one hand, it is so. But it is not because I have seen the facts that it is a terrible thing. And, again, there’s a paradox in that, isn’t there? I still consider Chernobyl one of the most profound and beautiful places I have ever been, and I feel a real affection for it. It’s as if any sense of modern life has been eradicated there — it’s almost frozen, even when people live their daily lives. The same is true in Fukushima. It is a paradox: tenacious and deadly, visible but invisible. I think it’s the same paradox, and I could try to compare Fukushima with Chernobyl.

-

From the Fukushima project. Photo: Donald Weber -

From the Fukushima project. Photo: Donald Weber

-

From the Fukushima project. Photo: Donald Weber -

From the Fukushima project. Photo: Donald Weber

Continuing the theme of the visible and the invisible, the book War Sand is a story about the sandy beaches of Normandy, where one of the most famous operations of World War II took place. Are the photographs of this sand through a microscopic lens work like a study of the events of the war on the same “atomic” level?

Oh! You compare an atom, which is invisible, to a grain of sand. I don’t think I meant such a direct connection, but it’s an interesting observation.

In Ukraine, I was intrigued by the relationship between what can be seen and what cannot be seen. After all, if we can’t see something, it’s still always there. We are looking at a large grain of sand, I can see it, but I cannot see what it holds inside. And if a regular camera can’t document it, like in Fukushima or Chernobyl, we’ll have to find another type of technology. That’s one aspect of this project started, and another is my grandfather’s stories.

So, I started working on War Sand with two completely different methods. One of them is quantitative, a kind of scientific; gathering of evidence. Seeing is knowing. And on the other hand — qualitative, mythical. Stories are supposedly present in us, and that is how we are in these stories.

Don, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Tell us more about the book and how you worked on each part.

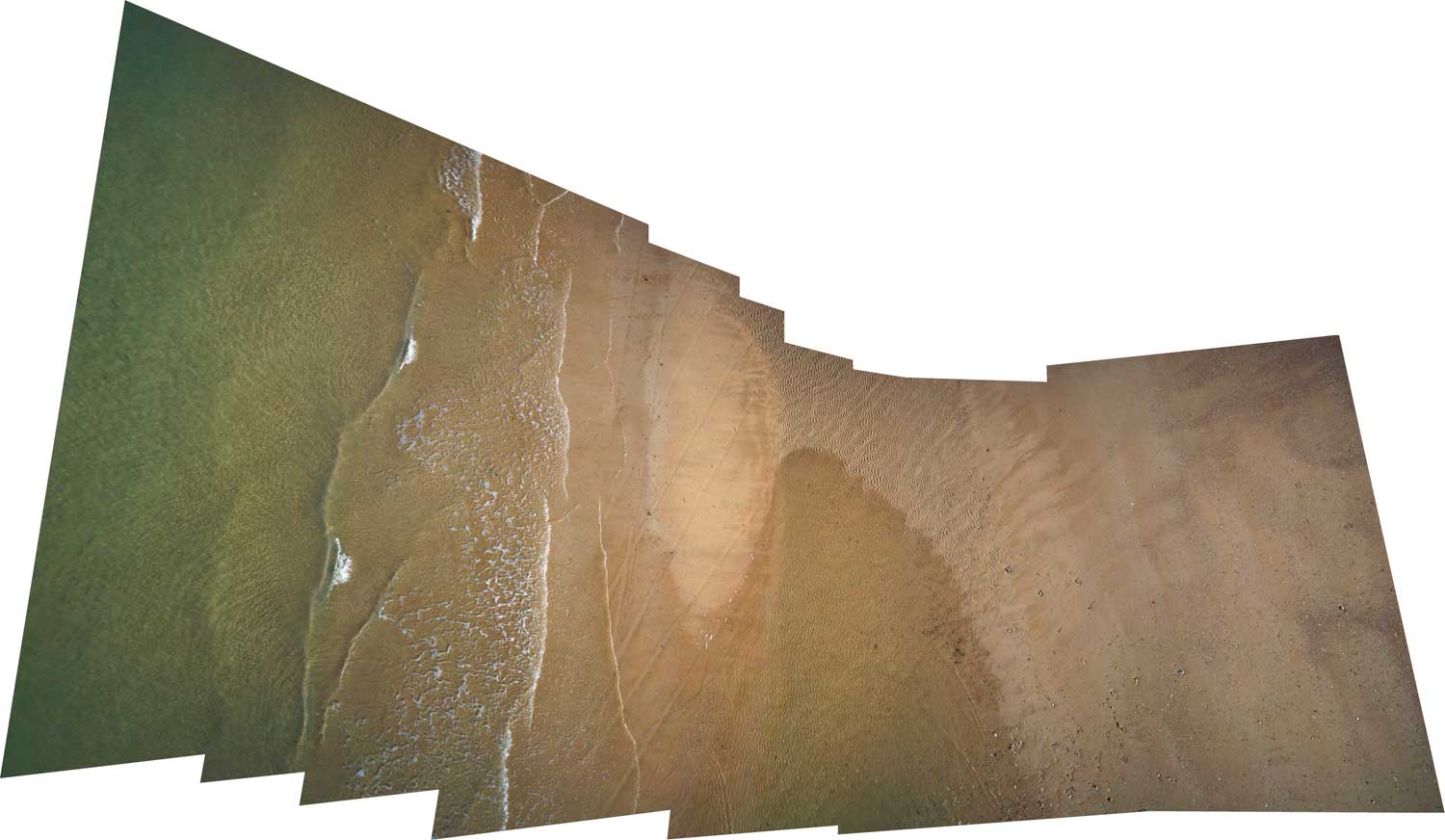

The book is difficult to explain. It is divided in half, and one part is the evidence. Evidence that day [the Allied invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944] took place on the beaches of northern France. The second part is devoted to the stories and cultural experiences of the battle. The first part is a reverse scale. Therefore, the book begins with a photograph of a cloud looking up. It speaks of space, of infinite space, of ultimate expansion. Then you look down, look at the landscape and see the sea. The sea is where this battle took place, but when I thought about it, I felt that the sea is prehistory; it’s like going back to the pre-dinosaur period.

-

From the book War Sand. Photo: Donald Weber

In many of the landscape photographs, I’ve always tried to leave little markers of the present — lines painted on the road, flagpoles, streetlights, fences, and things like banality in this sacred part for people from North America. Next, we go directly to the beach and look at the sand itself from the beach. We consider it at the microscopic level. And the sand idea was the first question I had when I started this project: does sand have memory? What stories are contained in grains of sand? Here everything began to open up.

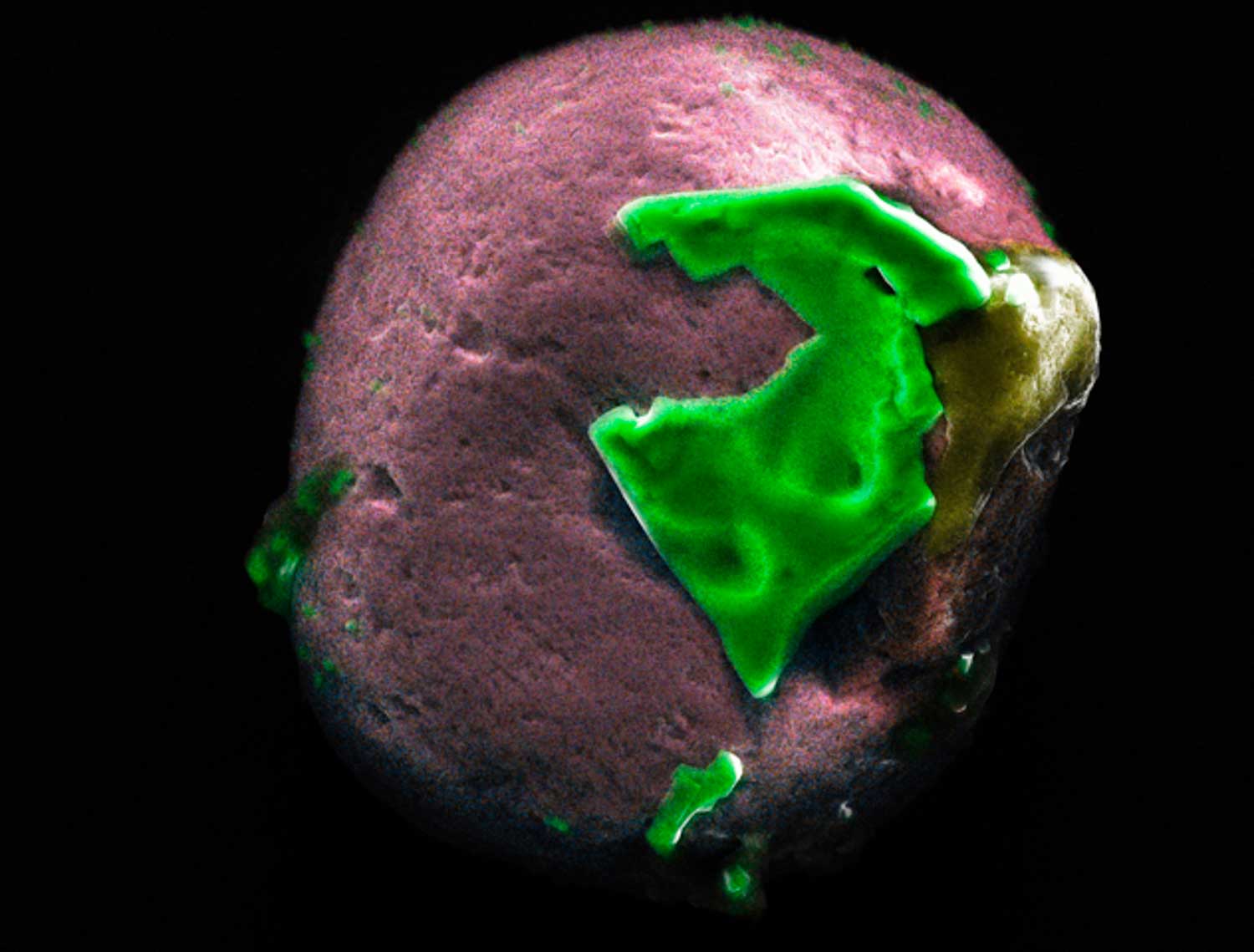

I worked with a scientist to create these images. And it was fascinating because we are looking at the sub-microscopic level, at something that you will never be able to see. And one thing I realized is that not only is the universe infinite, but these grains of sand are also infinite. So it’s like you’re going up into space, but you’re also going down. And it was like, “Oh my God, my brain will melt right now. It’s endless.”

-

From the book War Sand. Photo: Donald Weber

-

From the book War Sand. Photo: Donald Weber

While working on this part, we made a small discovery. It wasn’t my intention, but we found that many of these pieces on the beach were shrapnel from June 6, 1944, mixed in with the normal, natural grains of sand. These microscopic images are not only evidence, forensics, and notions of truth but also a million stories, an infinite set of stories contained within all these grains of sand.

And then, I started talking about my grandfather, who was a direct participant in the battle. He told me about the stories about her as a child, the concept of storytelling, and what it means to tell a story. Is the story true?

So yes, the idea of the book and its simple tagline is to look at war from the micron to the myth. Not just to look at it through the prism of forensic science but also from the point of view of mythological fiction. Then it’s all mixed together.

What prompted you to write this book – the story of your grandfather or still a question of memory, for example, the question of what a grain of sand remembers?

At that time, I had just left Ukraine because my period of stay had expired. It was a very tense period after the Revolution of Dignity. I wanted to rest. I watched some silly WWII movies they used to make in the sixties and remembered my grandfather’s stories. He used to tell me stories about the sand and these beaches. And this was a kind of motivating factor.

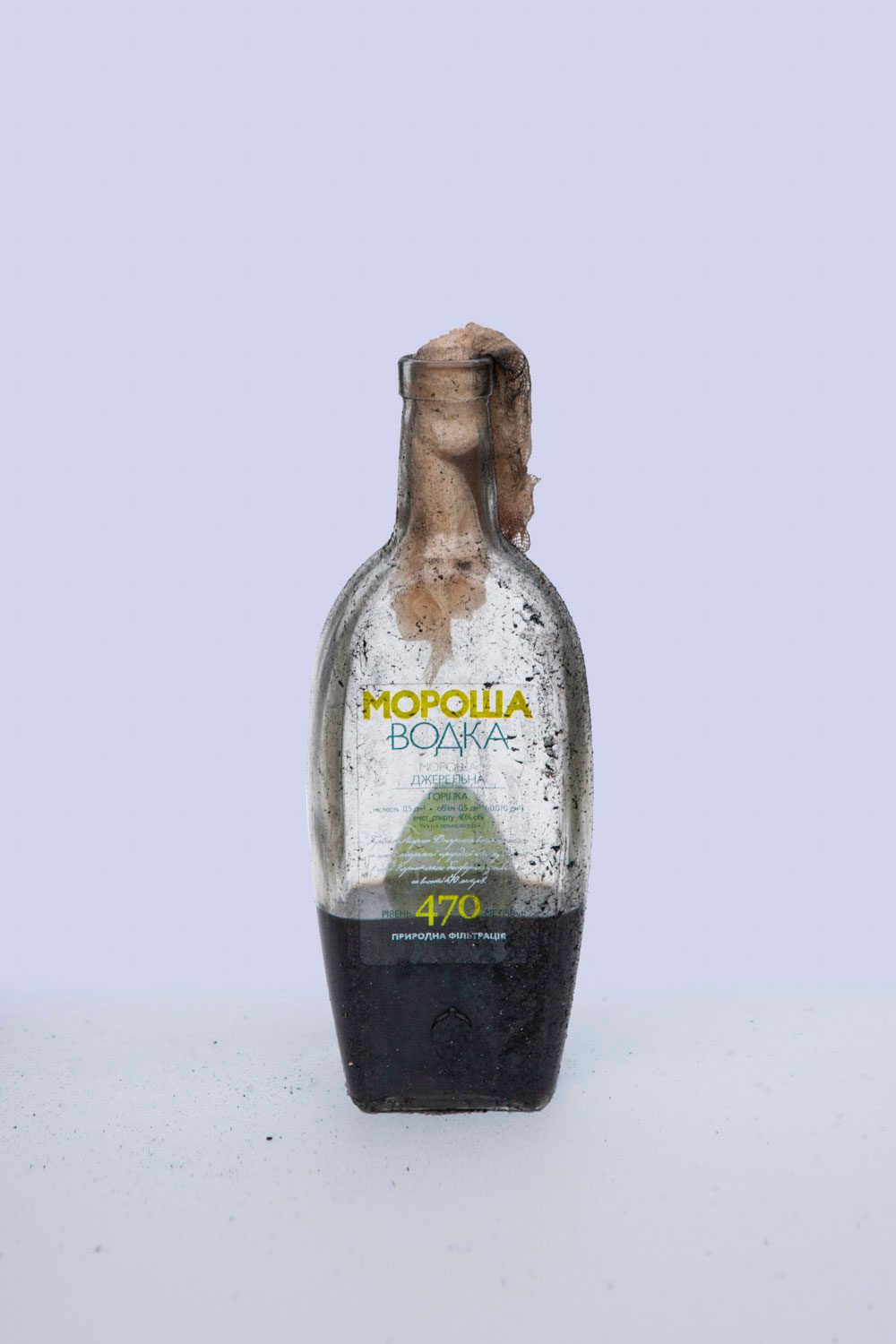

-

From the Molotov Cocktails project. Photo: Donald Weber -

From the Molotov Cocktails project. Photo: Donald Weber

So, the initial idea was this: sand has a memory. What kind of? [When approaching a new project], I didn’t want to use a camera and was thinking about what image processing technology I could use. So a friend of mine introduced me to a research paper that used a scanning electron microscope. It interested me, and I thought: what if I take ten grains of sand from these beaches, scan them and print them in a huge format?

So I went to France, stayed there for ten days, and walked the length and breadth of those beaches. I collected my sand. I really liked it — I liked the light, I liked the climate, I liked the landscapes. Even though I wanted not to take pictures, I couldn’t resist. Then I realized that maybe there was more to this project than ten images of sand.

I began to repeat: “Think about the landscape, think about the landscape…” It is how the project started to unfold. I worked on its creation for five years, and every six months, it expanded.

-

From the book War Sand. Photo: Donald Weber

Five years?

For the first three years, I explored, how should I say, all possible ways. So many different things didn’t even make it into the book. Oh my! Well, so many things! After three or four years, I knew what photos I should take. I have to make such a seascape, such a cloud. At one point, everything crystallized. I’ve had a few trips where I’ve been very specific about what I have to photograph. I started thinking about it as a book somewhere around this point. I love books. I believe this is an excellent authorial form of storytelling. And then, after five years of filming, I spent, I think, six or eight months finalizing the book itself, although I started writing it almost immediately.

You turn most projects into books. Why do you think a book is the best medium for communicating with the audience?

War Sand is, on the one hand, a very exclusive book, but at the same time, in my opinion, it is very inclusive. And one more thing that brings me back to my youth. Everything seems to get me back to my youth. I vividly remember one day being in my high school library and pulling out a book — just a random book — opening it, and a page fell out. It was a card, but a very good card. There was something about this experience of being in a library and accidentally discovering something that hooked me — the surprise, the bewilderment, the beauty. When I started working on War Sand, I envisioned that someone like me would pick up a book off the shelf, hopefully, some 15-year-old kids, and they’d open it and be like, “Oh my God, what are these weird images? What is it?” And they will be confused by what they see.

-

From the book War Sand. Photo: Donald Weber

-

From the book War Sand. Photo: Donald Weber

-

From the book War Sand. Photo: Donald Weber

-

From the book War Sand. Photo: Donald Weber

Imagine a bookstore. A box of new books comes to it, the workers open it, start taking out the books, and come across War Sand. They look at it and think: “What is this? Is it a photo album, is it a book about art, is it a book about history, war, geography, or geology? What the hell is this? What section does it belong to?” I like the book’s spirit, where you can play with expectations because of its content.

I purposely made War Sand as an expensive library book. And so it happened that the primary audience of this book is libraries. It was actively sought out and ordered by various public and academic libraries throughout the United States and Canada. And I hope that someone, I don’t know whether today or twenty years from now, will pick up this book. And this will be a kind of axis of surprise.

I could never figure out how I could convey that story in, let’s say, an exhibition. In addition, the exhibition is a temporary phenomenon. It disappears after a few months, but I’ve also never liked to think digitally, for example. How can I convey this magic of sequence and unexpected connections through a number?

-

The book War Sand. Photo: Donald Weber

So you don’t believe in digital, multimedia storytelling formats?

There are excellent examples in The New York Times or Post and materials from the National Film Council of Canada. There are really incredibly interesting materials created in digital format. But their creation requires infrastructure. I can tell a good story, know how to tell a good story, and do it visually. But the next level of storytelling, in this case, will be a skillful mastery of various digital technologies to convey it. For me, that would mean getting someone else involved.

My stories are just me. I like this intimacy. I like the fact that the paper has a degree of affordability. It seems paradoxical because you think about history distribution in digital format and social media. What I loved about the book business was the magic of surprise.

-

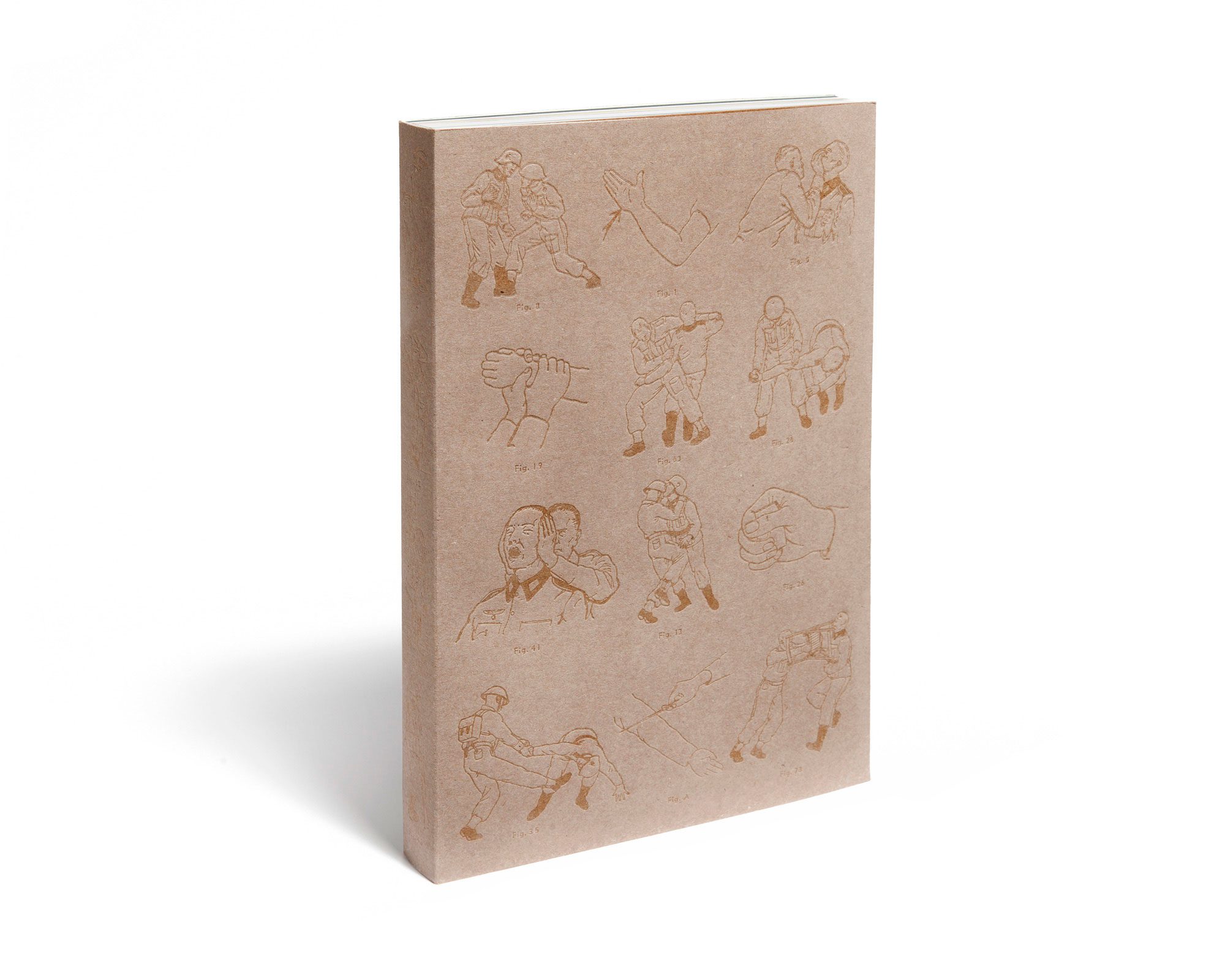

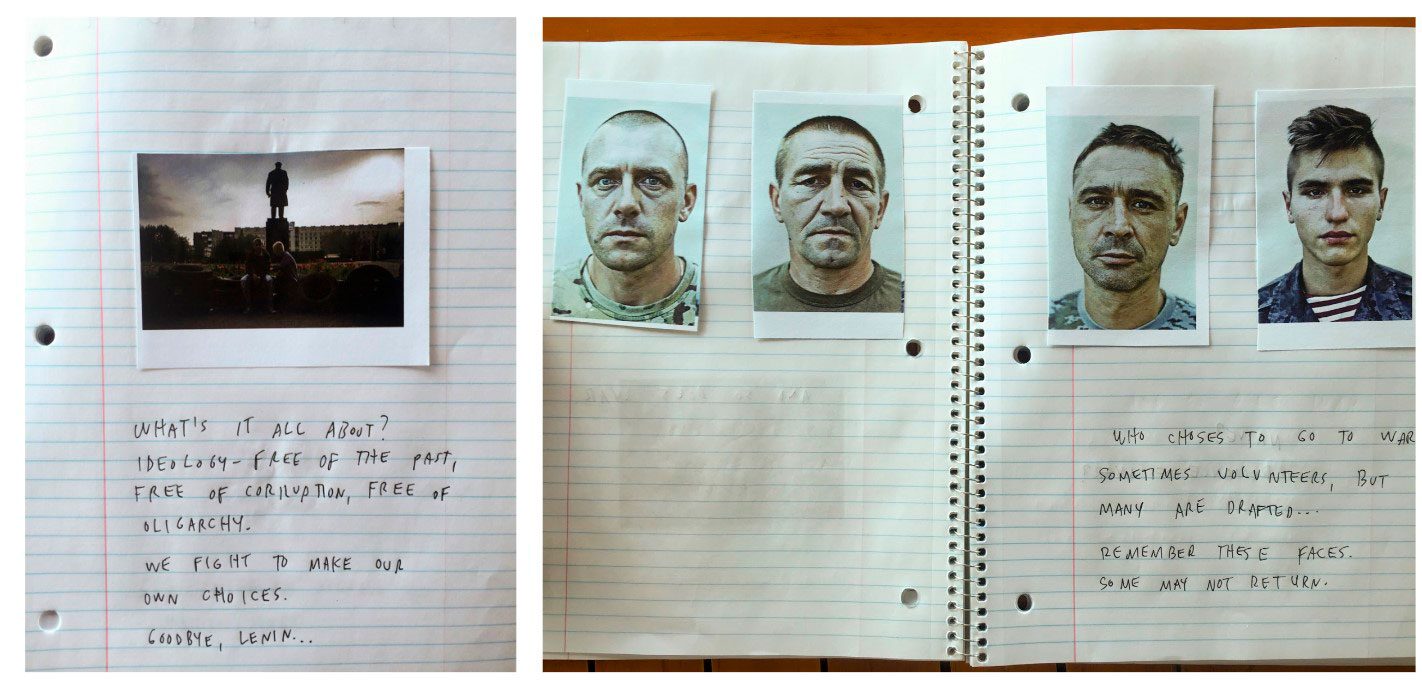

Donald Weber’s sketch for the book RAW, dedicated to Ukrainian military personnel who participated in the conflict in Donbass in 2013-2016.

You often work on historical themes, turning to the past to understand and understand the present. Are there any time limits when we can begin to reflect on tragic historical events?

Good question. I think that at any time. I mean, you can quickly look at the current situation, the war in Ukraine. How could I react to this? When the horrific mass murders are happening, it’s all happening right now. I don’t have an answer to this question, but I think it’s a concept of subjective history. You use it as a kind of lens, pushing and pulling these different, shall we say, historical trajectories that are current. It sounds vague, but it brings us back to the sensitivity issue. To the position — who am I? Where did I come from? What is my relationship to what is unfolding before me? And how can I find a way to understand or perhaps respond to what is happening?

-

From the project Quniqjuk, Qunbuq, Quabaa dedicated to the indigenous population of Canada. Photo: Donald Weber -

From the project Quniqjuk, Qunbuq, Quabaa dedicated to the indigenous population of Canada. Photo: Donald Weber

-

From the project Quniqjuk, Qunbuq, Quabaa dedicated to the indigenous population of Canada. Photo: Donald Weber -

From the project Quniqjuk, Qunbuq, Quabaa dedicated to the indigenous population of Canada. Photo: Donald Weber

Photography is full of strange contradictions and a fantastic vehicle for openness and sensitivity. But at the same time, it impresses and sets certain representations of narratives in their place. And here, I think you have to be careful about why, when, and how you use photography. It is why I return to the notion of a subjective historical position because I am not proclaiming but trying to be inside and react through a specific intuitive lens to what is happening.

You started talking about the war in Ukraine, so my last question will be about the war. Now we see many powerful, tragic, excruciatingly painful photographs of the war taken by photojournalists worldwide. But at the same time, I see many unsuccessful attempts to reflect this conflict. Some of it seems to be just hype and an opportunity to capitalize the suffering, death, and destruction caused by Russia. What do you think about it?

This question is difficult to answer. On the one hand, I feel the impulse and desire of Ukrainian artists, photographers, and cinematographers to respond to the war in some meaningful way. And I think art is a way of finding meaning and making sense of something. Yes, we can look at war purely from a forensic point of view, from a scientific point of view, but that does not necessarily put us in a broader, let’s say, relational position.

I was interested in the work of Vlad Krasnoshchok. He is from Kharkiv, and he reacts to how his native city is being transformed and destroyed before his eyes. The events recorded by him change him as well. In this sense, I was very impressed or intrigued by how he reacts to the immediacy of what is happening around him. And in addition to, let’s say, the photojournalistic impulse — fixation — he uses his visual language. Or, for example, Mykhailo Palinchak. He works as a photojournalist, but the photos I see — I feel through them that all this [the war] is very deep inside him; this is a psychological breakdown that happened to him and his country.

In my opinion, the only thing that is important to understand is that the immediacy of the photographer as an artist, in this case, is more important than the straightforwardness of the photojournalist.

But when it all gets out of hand — and it’s getting out of hand now — it becomes problematic. I’m a big fan of art and culture as a means of making sense, and I understand that people want to go there [to war] and try to make sense of it. But the scale of the trauma and devastation leaves me puzzled about how, why, and when we can work with it artistically.

-

From the Molotov Cocktails project. Photo: Donald Weber