“Full-Scale War Has No Location, It Affects Everyone.” Lysychanska Gallery Published an Art Book About War Experiences. That’s What It’s About

In January 2023, the team of the Lysychansk “Gareleya Neotodresh” published the book “View from two thousand yards,” which collected the stories of Ukrainian artists and their experience of the first six months of the war. The book presents 62 visual stories from 64 artists about bomb shelters, escape from enemy missiles, occupation, death, and forced emigration. Zaborona tells the story of the creation of Gareleya and whether it is possible to see the future at the end of the two-thousand-yard gaze.

Vitaly Matukhno was 24 years old before the beginning of the full-scale invasion, and he did not think of leaving his native Lysychansk — a not very culturally developed industrial mono-city. From the age of 18, he tried to change the city’s cultural environment: he volunteered at art festivals, engaged in cultural activism, organized exhibitions, and invited artists and musicians from the Luhansk and Donetsk regions.

“The idea that I can change something in the city touched me. I understood even then that I would not leave the city, and if I do stay, I will try to add something from myself,” says Matukhno. With his friends, Vitaly began holding exhibitions in abandoned factory buildings in Lysychansk or in his apartment, which had been renovated, and no one lived in it anyway. It all started as a non-conformist project that opposed itself to the mass culture of the city and the paradigm of events sanctioned by industrial enterprises, such as “Miner’s Day.” Subsequently, “Gareleya Neotodresh” became a fairly prominent representative of the formation of young artists in Eastern Ukraine.

Vitaly Matukhno. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

“At first, I thought it would be a local punk anarchist project that I would do for nothing — with my funds, at the expense of my friends, whom I can find or ask. I didn’t borrow money; I just asked for a donation. The first exhibition cost us 500-600 hryvnias, the second — 1,000 hryvnias.”

The curator calls the disparity and separation of the cultural community from city to city one of the most critical problems that arose during the work. The “Aura of the City” residence from Starobilsk and the “Lugansk Contemporary Diaspora” — according to Matukhno — did not cooperate. Each cultural organization occupied its niche and worked according to its priorities. Attempts to combine artists in one cultural project were almost always ineffective. Summarizing, Vitaly says there were quite different contexts and vectors of development everywhere. It is impossible to compare Lysychansk with Starobilsk, and the isolation of communities is present throughout Ukraine.

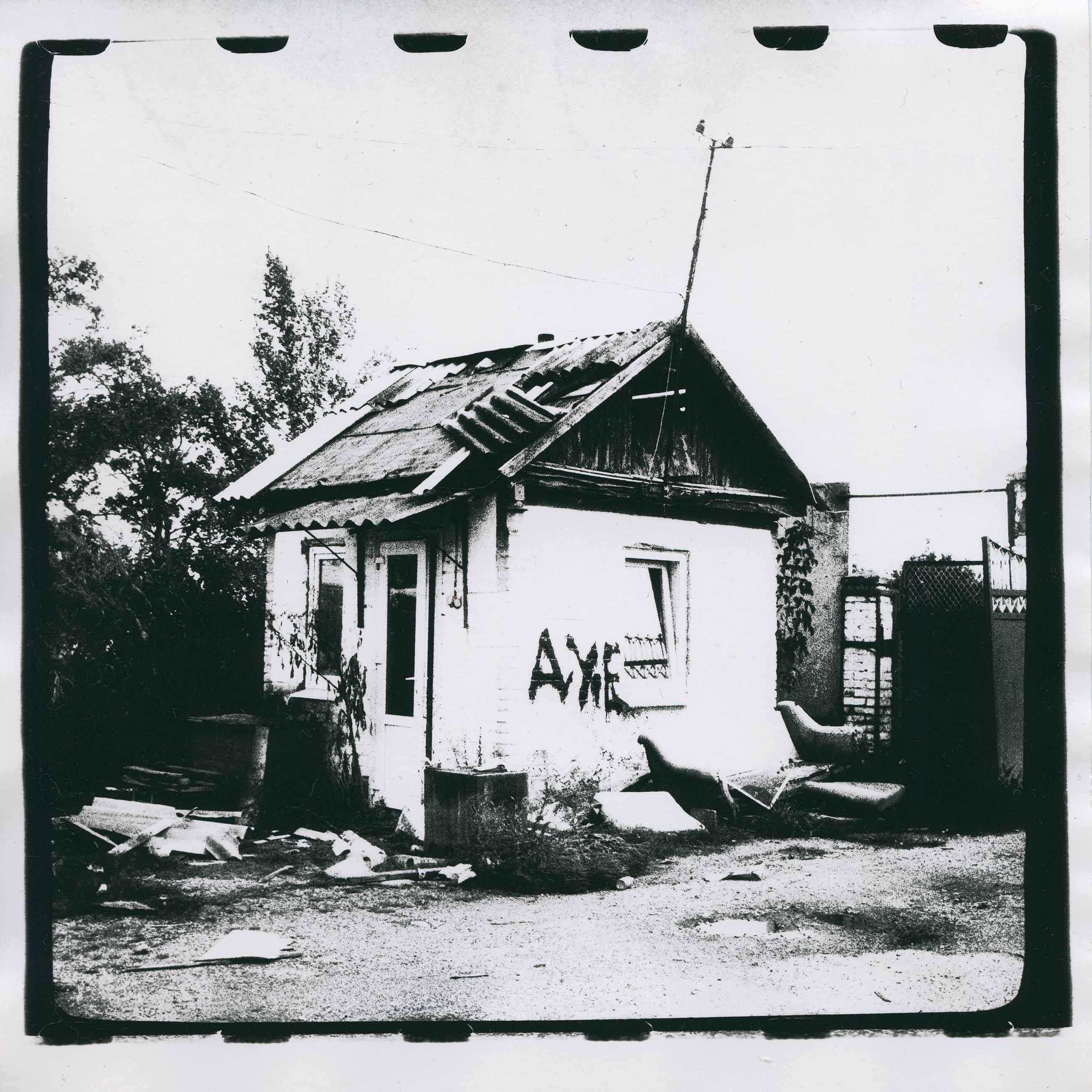

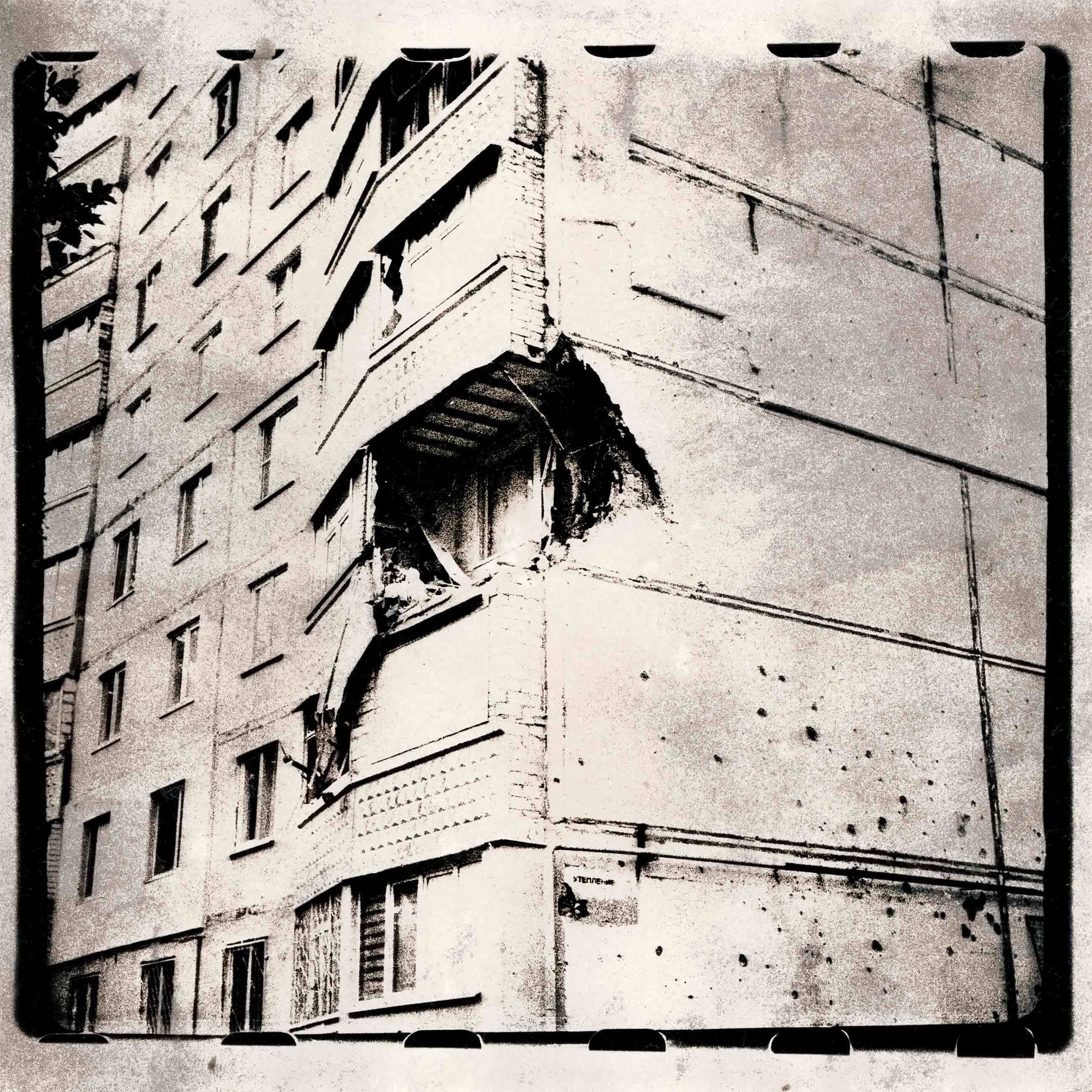

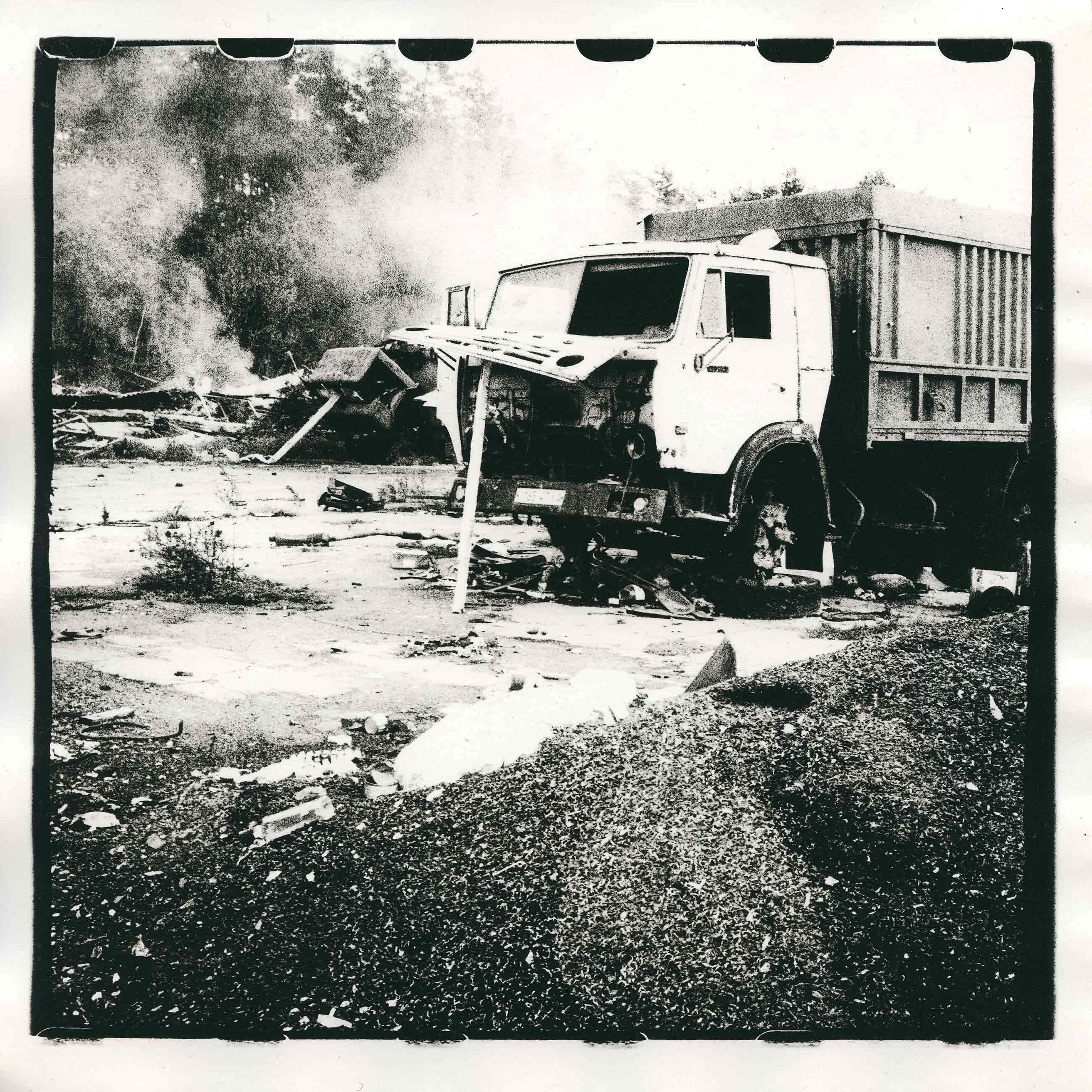

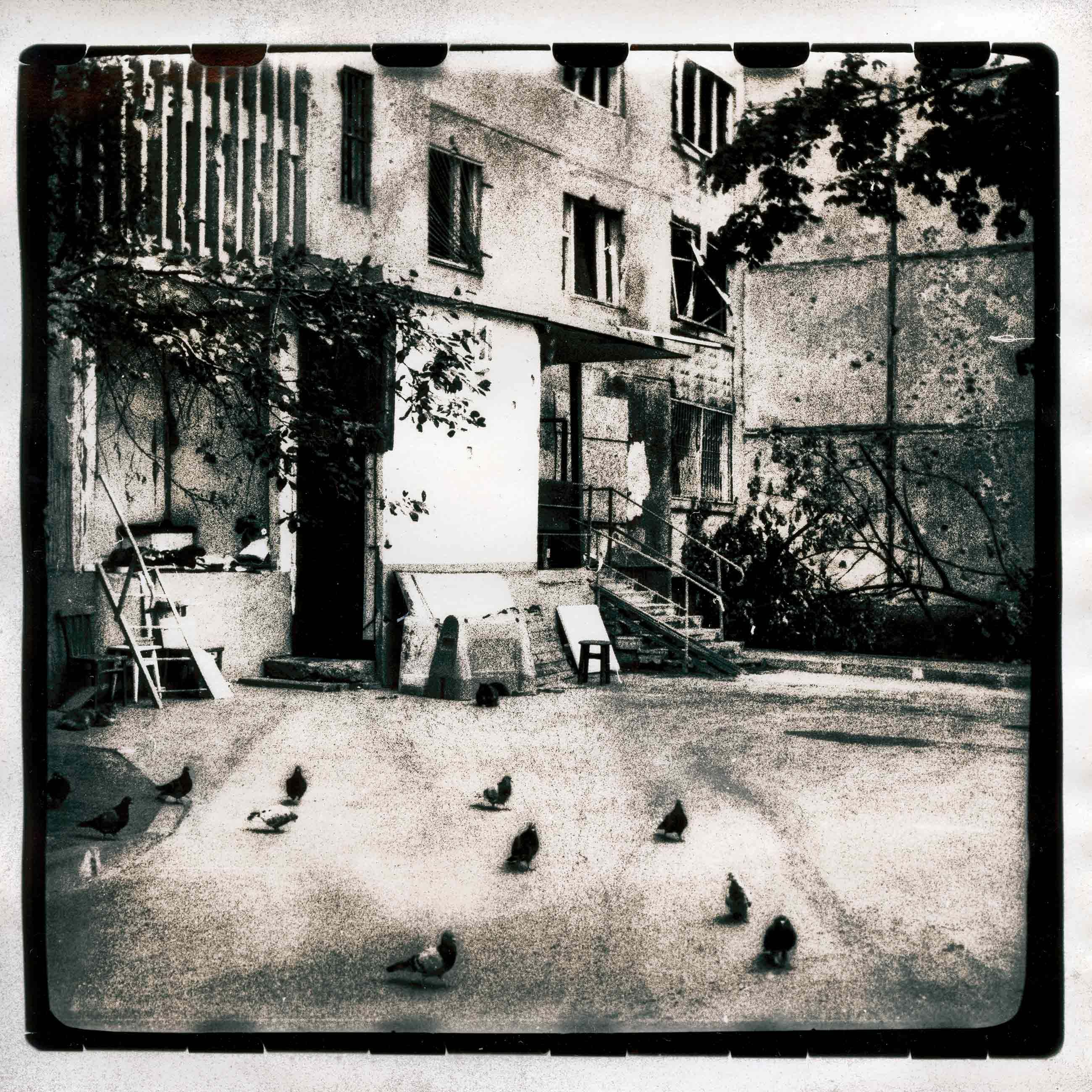

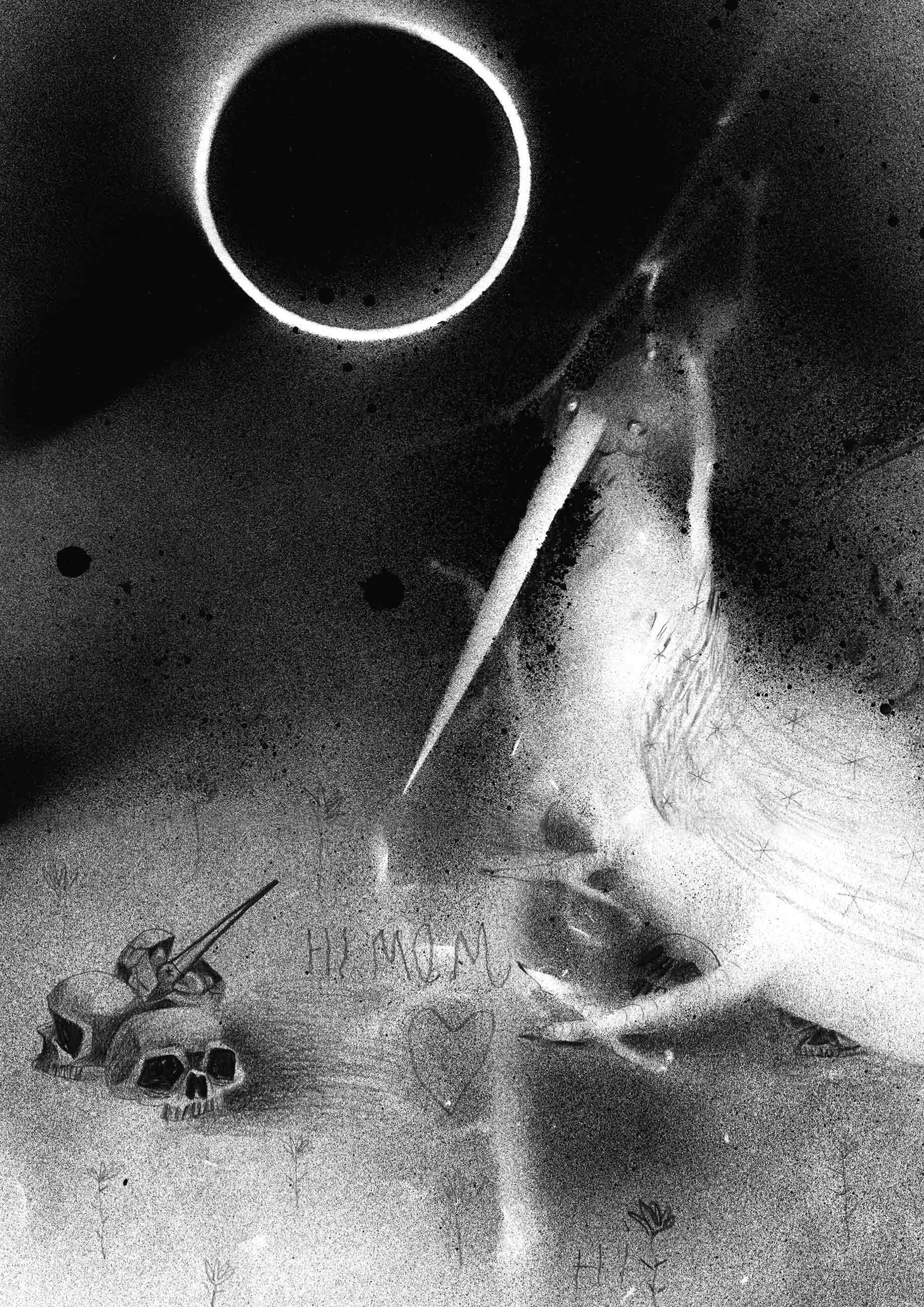

Rodion Prokhorenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Rodion Prokhorenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Rodion Prokhorenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Rodion Prokhorenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Rodion Prokhorenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Rodion Prokhorenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Rodion Prokhorenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Rodion Prokhorenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Rodion Prokhorenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

In 2021, the Neotodresh team created the first zine. If the gallery format and the events created by the project did not have a clear structure or limitations, the zine did. It is a limitation on the number of pages and their orientation. The zine was published in 500 copies and had 240 pages. The art book focused on the creative practices of artists from the Donetsk region and Luhansk region. The book became a printed version of the exhibitions held by the gallery but was completely autonomous and had a wider geography.

The curator never called the activities of “Gareleya” institutional. Not only did she never have her own space, but also because DIY events reached a minimal audience.

“No matter what kind of punks we consider ourselves to be, at the beginning of our activity, we still tried to take an institutional approach: we did a lot of events, and we always tried to expand the geography. Everything was going quite logically for us, and the zine was a logical continuation and a step forward. I have never considered a gallery an institution, but I have always tried to maintain this consistent approach to work. Sustainability is important because the information space is always oversaturated, and various things are always quickly forgotten.”

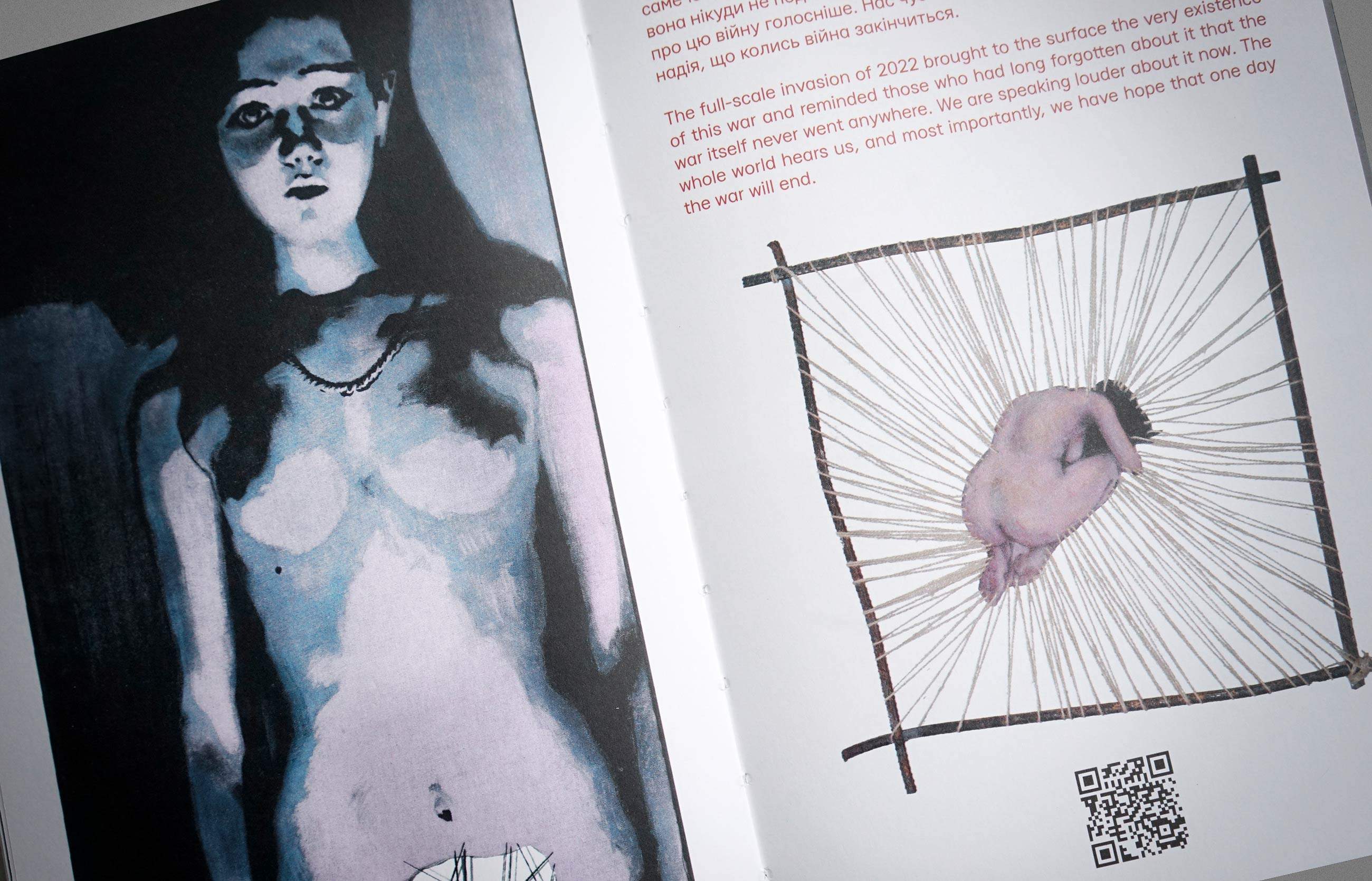

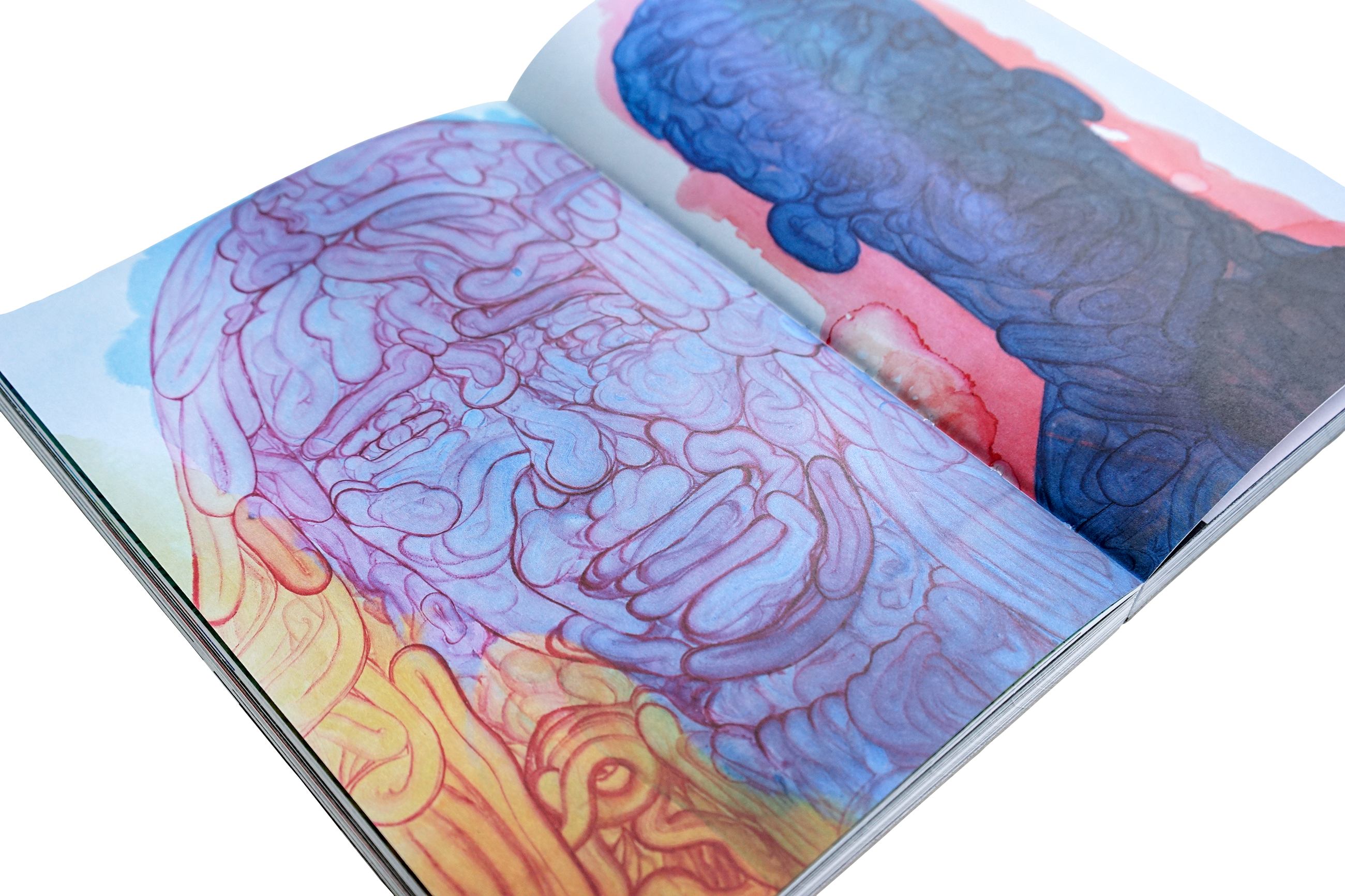

Pages of “A View of Two Thousand Yards” with the works of Yulia Shayakhmetova

Stability has not disappeared since the beginning of the war in Ukraine. Matukhno, like a large number of artists from the East, had to evacuate and move to Lviv. Other members of the team moved around Ukraine and abroad. But they did not stop their activities.

“A full-scale war has no location as such; it affects the whole of Ukraine,” says the curator. Therefore, the second book made by the gallery team does not focus on the art of Donbas but is entirely devoted to reflections on the full-scale invasion of Russia into Ukraine.

“A full-scale war has no location as such; it affects the whole of Ukraine,” says the curator. Therefore, the second book made by the gallery team does not focus on the art of Donbas but is entirely devoted to reflections on the full-scale invasion of Russia into Ukraine.

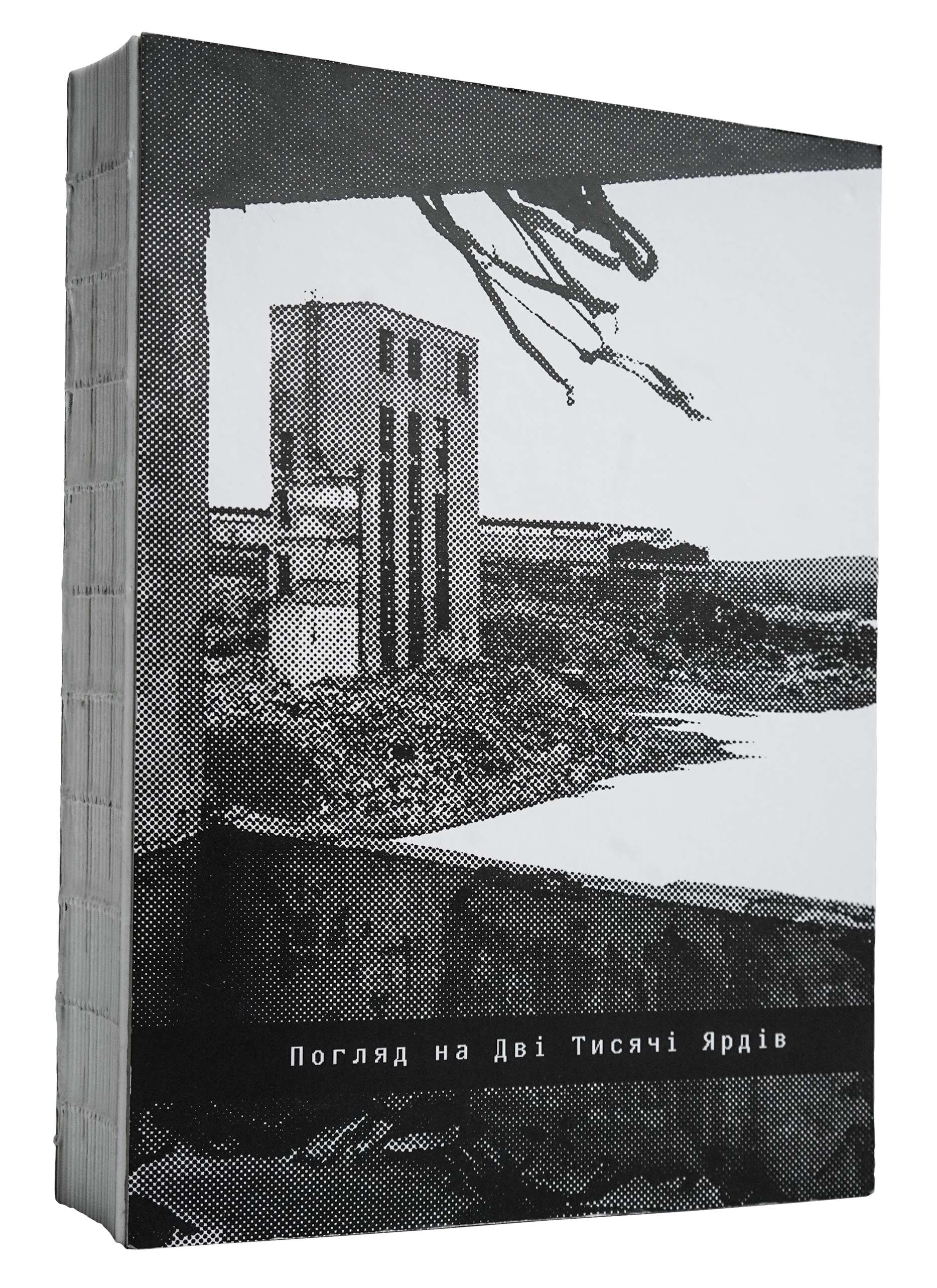

A book cover of “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

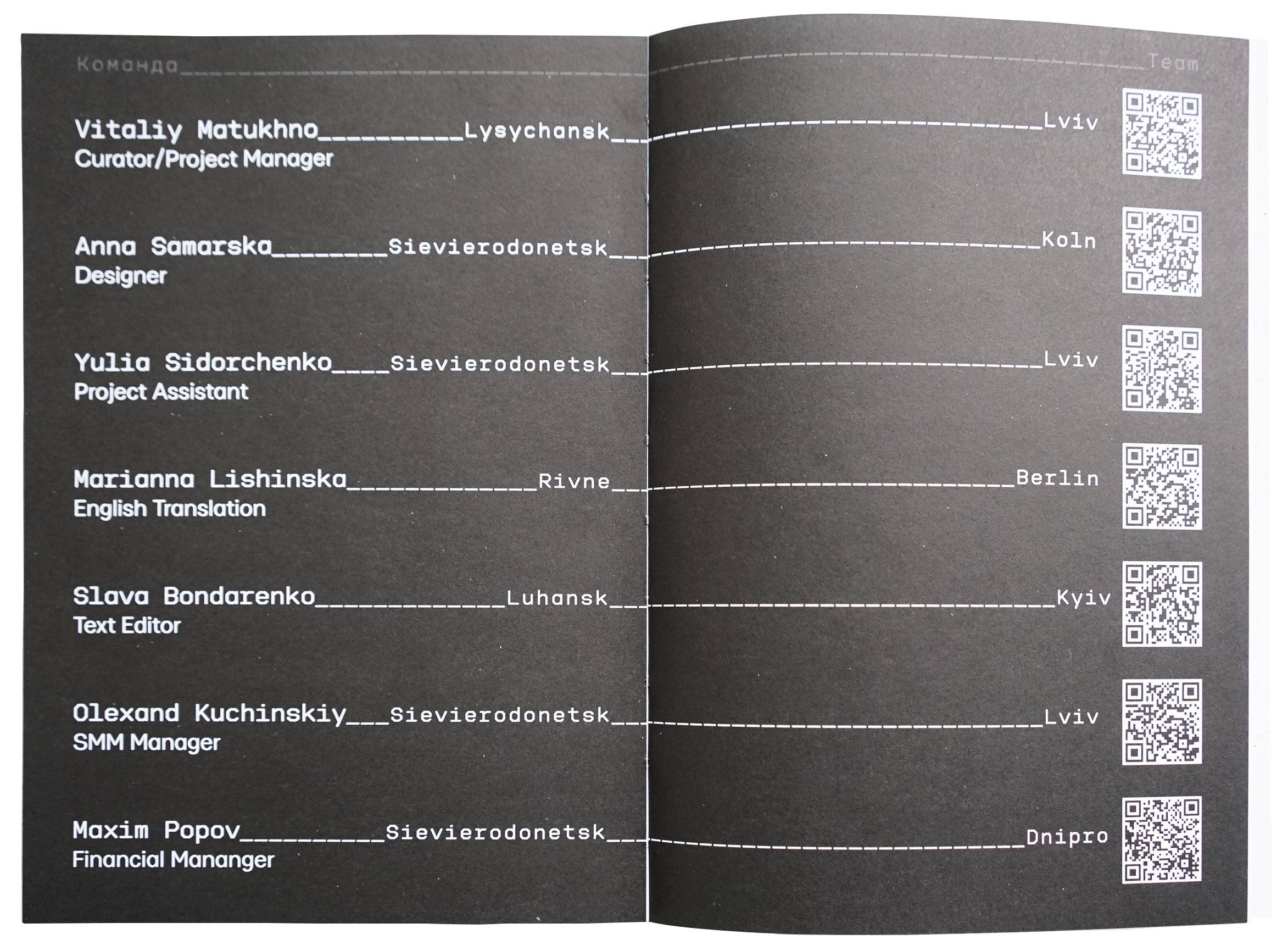

A page listing the members of the Gareleya Neotodresh team, their hometowns, and the cities they had to evacuate to when the full-scale war in Ukraine began.

For Matukhno himself, “View of two thousand yards” is a continuation of the logic of his activity and the gallery activity. The invasion of the Russian Federation in 2014 was a pain and fear exclusively for the eastern regions of Ukraine. The second book tries to give voice to as many people as possible: “View” became a place to visualize the tragedy of war for artists from all over Ukraine.

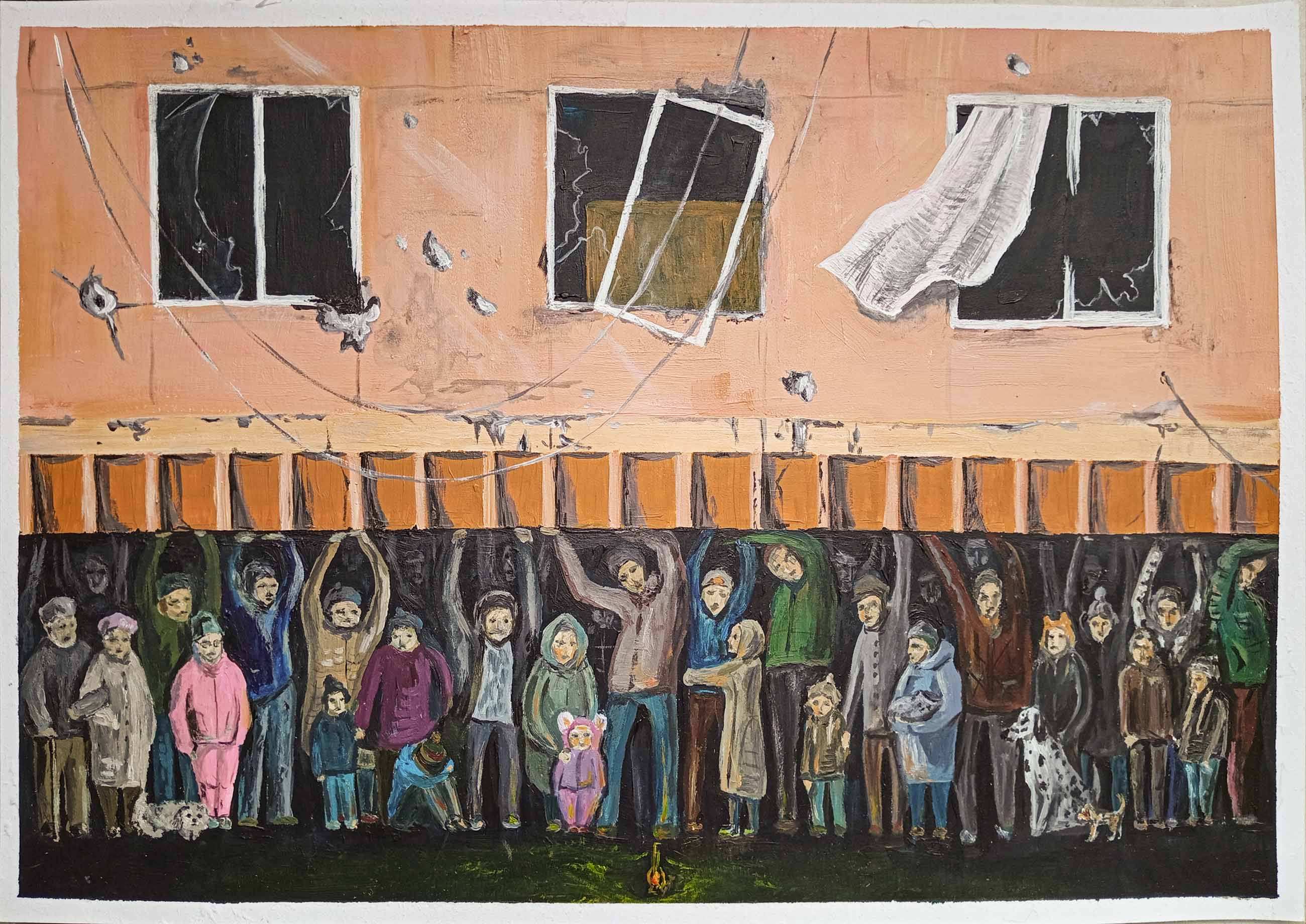

Alina Panasenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Alina Panasenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Alina Panasenko, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Eva Sigachova visualizes her stay in occupied Mariupol, depicting the corpse of her neighbor fireman, uncle Kolya, who extinguished the fire in Eva’s house four times. Eva’s family remained alive thanks to him, but she cannot forget the cold blue corpse in the entrance for a long time, even today.

Volodymyr Prylutskyi and Oleksiy Chistotin document their stay in a refugee shelter in Lviv. As a recently cheerful and noisy student dormitory turns into an anthill filled with people, in which new social connections and meanings of relationships are built.

Volodymyr Prylutskyi and Oleksiy Chistotin, “Temporary Residence”. Works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Volodymyr Prylutskyi and Oleksiy Chistotin, “Temporary Residence”. Works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Volodymyr Prylutskyi and Oleksiy Chistotin, “Temporary Residence”. Works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Volodymyr Prylutskyi and Oleksiy Chistotin, “Temporary Residence”. Works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Volodymyr Prylutskyi and Oleksiy Chistotin, “Temporary Residence”. Works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Volodymyr Prylutskyi and Oleksiy Chistotin, “Temporary Residence”. Works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Volodymyr Prylutskyi and Oleksiy Chistotin, “Temporary Residence”. Works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

In the picture, “Mom, where’s dad?” Olenka Kravchenko shares her experience of staying in occupied Gostomel. People hiding in basements, out of touch with the outside world, scared and hungry, but alive. Alive but officially recognized as missing. The central figure of the picture is three-year-old Zlata Morozova, who constantly asks her mother about her father. On March 17, 2022, the Russian military took the people from the basement to Belarus, the girl’s father, Oleksiy Morozov, is still in captivity in the Russian Federation.

Olenka Kravchenko, “Mom, where’s dad?” Work from the book “The Two Thousand Yard View”

The works included in the almanac were collected using an open call. “It was important for us to collect people’s experiences, which they implement in art. The journey they experienced themselves,” explains the curator.

In less than a month, the project team received 255 applications, of which 64 projects were included in the book. According to Matukhno, the book contained more authors than planned — some were invisible, artists from the occupied territories.

Olga Lisovska, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

Olga Lisovska, works from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”

“We have been working with artists who were under occupation from the first days of the creation of Gareleya. It has always been important to me. There is pro-Ukrainian youth who are engaged in art but live in the occupied territories. No one knows about them, it’s as if they don’t exist. It was important for me to prove their existence. From the first days of creating this project, I understood that our region is already quite divided into two parts, and I do not want to continue this division in my project. I want to unite people,” says Matukhno.

The cover of the book “A View from Two Thousand Yards” with the works of Mykhailo Tarasenko

Svitlana Gavrylenko from Simferopol shares the fears she has experienced in the occupied Crimea for 9 years in her works, made in mixed media with oil and acrylic paints. The war intensified the terror of the occupation authorities, and people were intimidated and driven into a corner — those who tried to say something disappeared.

“Every word of honor is despite fear: what if I will be the next one to disappear?” says Havrylenko. “Every picture, exhibition, and charity auction is a sentence. People in uniform can come anytime. One can only hope and not unpack the alarming suitcase. But I see the only way to remain a person and an artist is not to be silent as loud as possible.”

Svitlana Havrylenko, a work from the book “A View of Two Thousand Yards”