Welcome to Coal-Hill. For 8 Years Now, Michał Łuchak Has Been Photographing Coal-Mining Towns in Upper Silesia That Are Gradually Sinking into the Ground. These Are the Photos

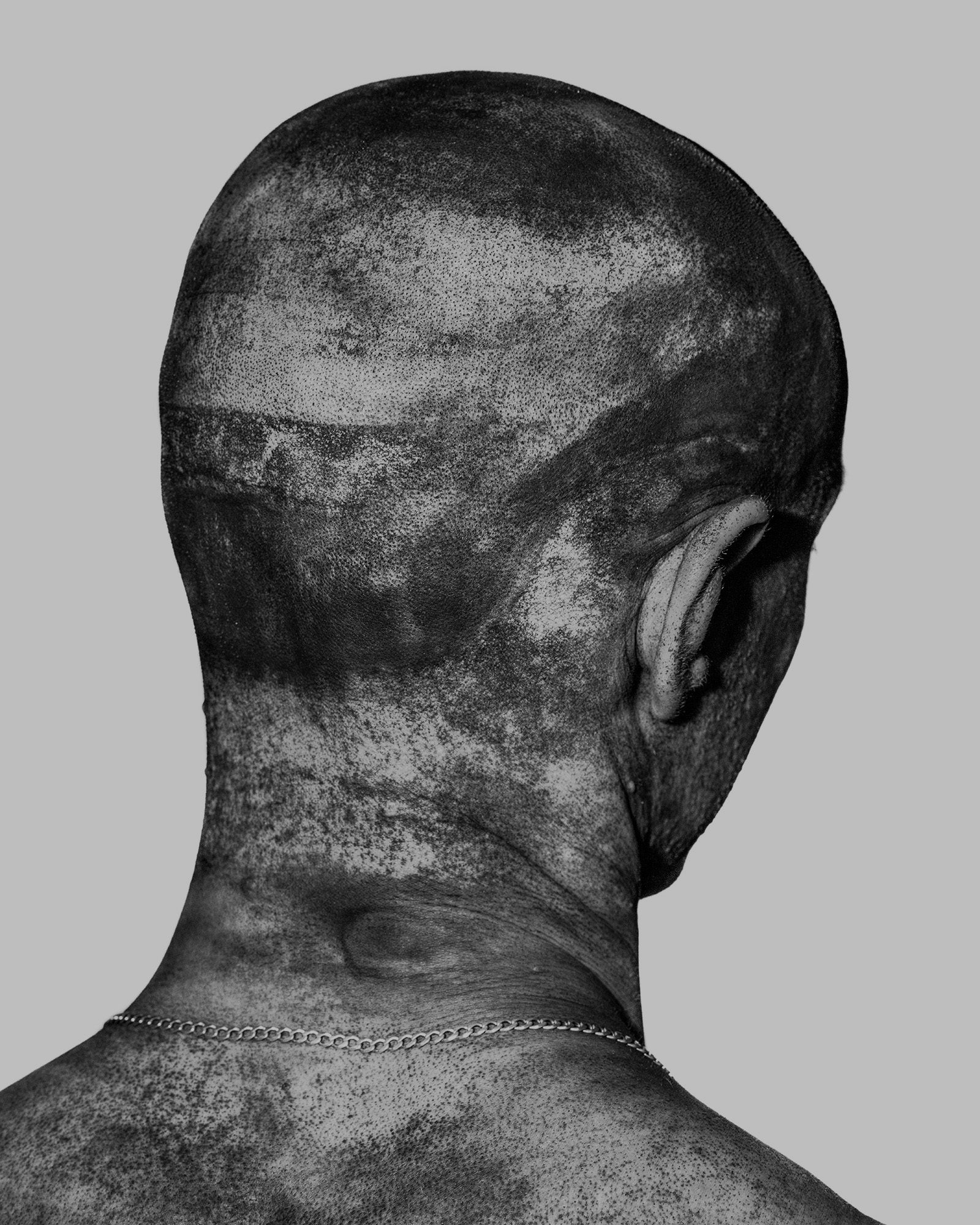

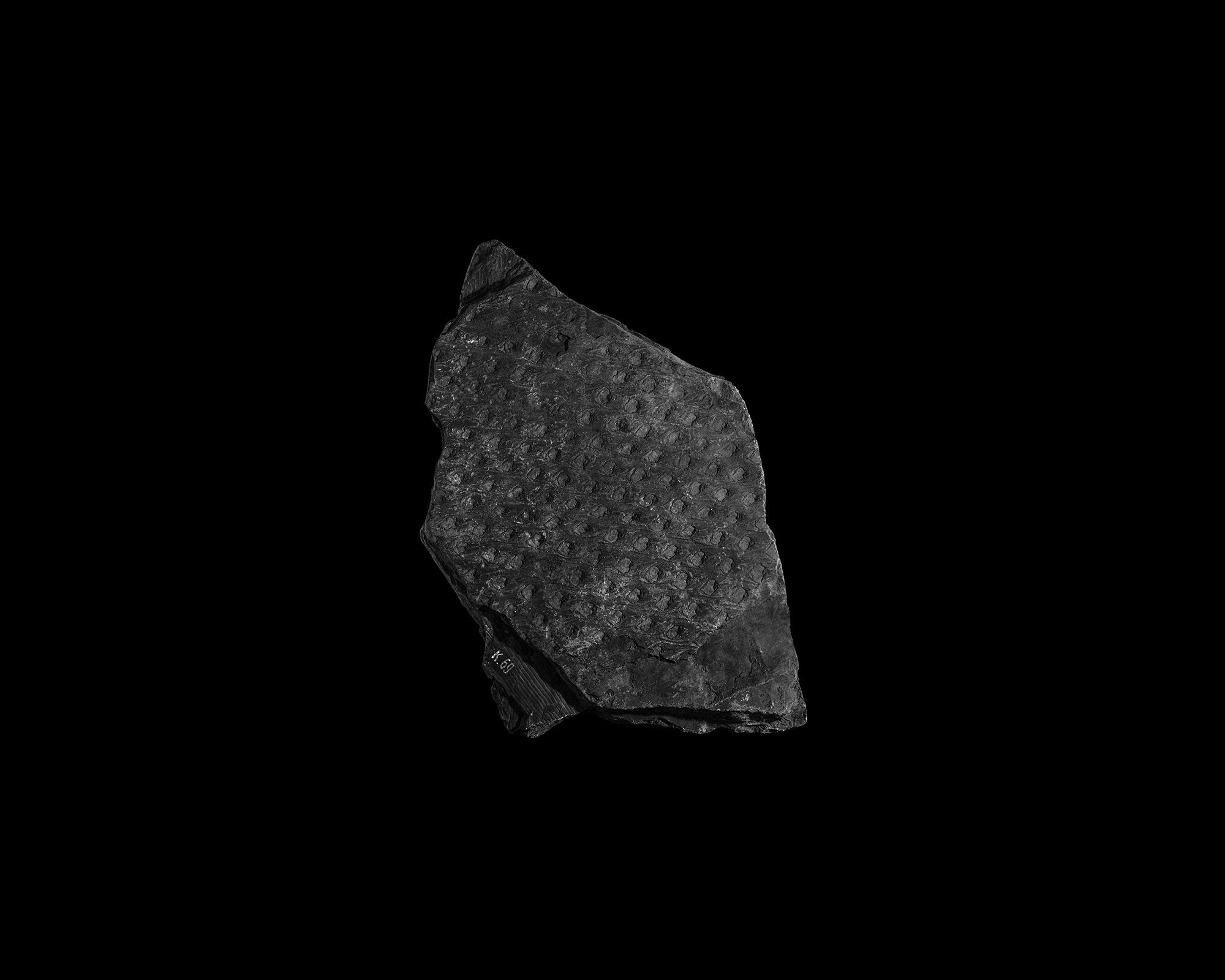

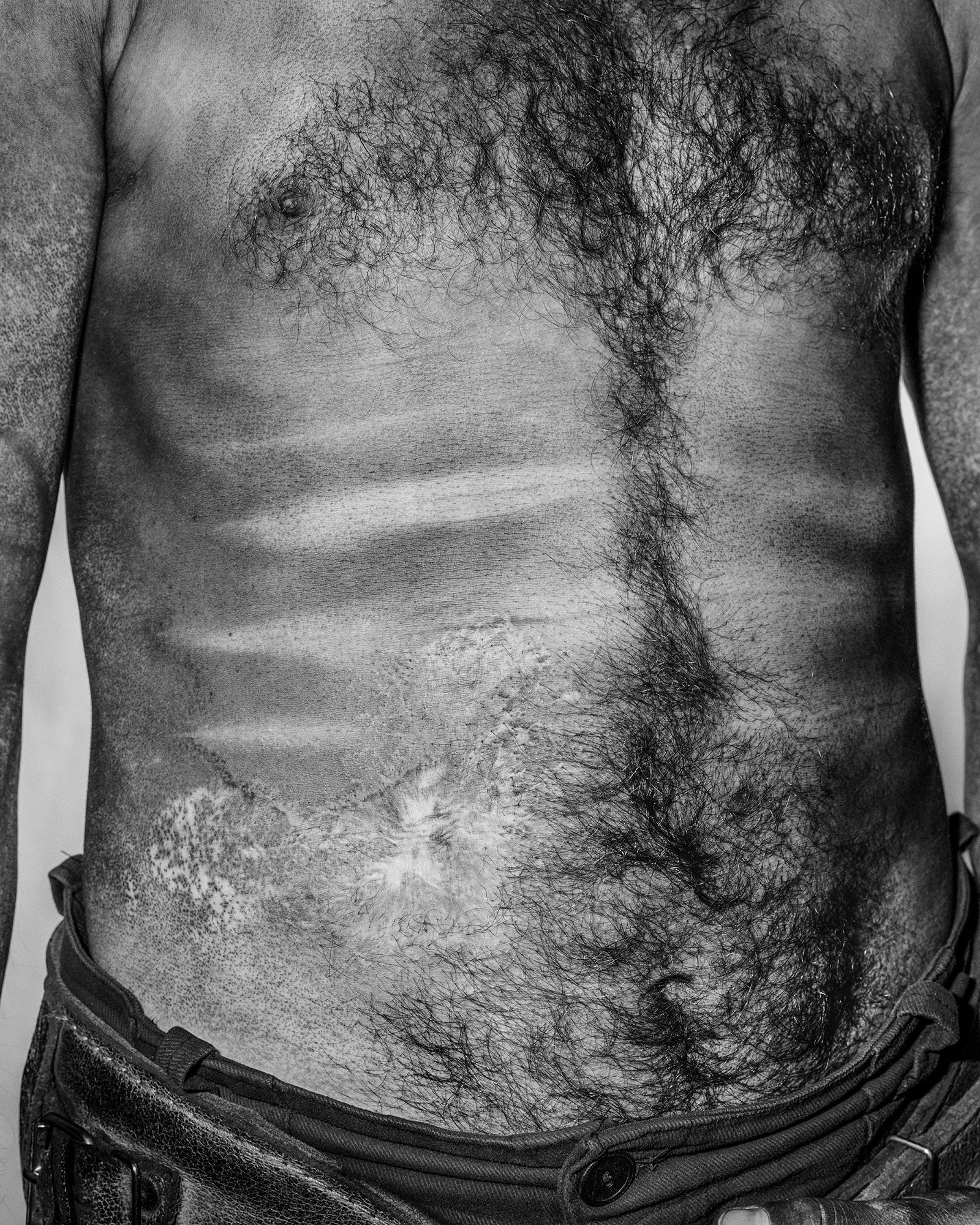

Since 2015, Polish photographer Michał Łuczak has been documenting the effects of coal mining in the industrial region of Upper Silesia in his series of photographs called Extraction. Łuczak explores the effects of industry on the body, the dynamic change of the landscape, architecture, and urbanism that are transformed or disappear — due to mining or air pollution. The photographer is looking for answers to strange questions: why does his house shake, why is it crooked, why does the air stink in winter? Zaborona publishes his visual research and textual notes.

I was born, grew up, and continue to live with my family in Upper Silesia, a region in southern Poland where coal has been mined on an industrial scale for over 200 years.

My photographic documentation of this region is not influenced by any particular event or memory from my childhood, except for one thing: I was born here. This does not mean that I have a special understanding of the region. After living in many places in Western Europe and Poland, I finally returned to Katowice in 2010.

The house where I live has tilted noticeably, although we, the residents, no longer feel the tilt. A few hundred meters below us, the sidewalks dug decades ago are gradually sinking into the ground, this is the result of mining operations that hollow out the ground beneath us.

Across the street from my house is a spoil heap, a large mountain of waste from mining that is slowly overgrown with pioneer plant species. Eventually, the mountain will be gone when someone uses this waste as a raw material for road construction. In the immediate vicinity of me, there is a mine that extracts coal from a depth of over 1000 meters. Another mine was closed a year ago after 135 years of operation.

In winter, you can see how stinky the air we breathe is. Unfortunately, I am contributing to this myself, because, in my crooked house, there is a coal stove in the basement that burns what someone has rosily called eco-peal coal.

Since 1989, when the communist regime was overthrown in Poland, Upper Silesia has undergone a transformation. Most of the region’s mines have been closed because the deposits are exhausted or the seams are too deep to be profitable. Recently, the Polish government announced that by 2049 there will be no coal mines left in the country. However, some experts argue that this will happen much sooner.

The Upper Silesia region is changing quite dynamically now. The places that I shot before 2020 in Bytom, a city that suffered the most from coal mining in terms of architecture and its decay, were falling into disrepair. However, the city is now repairing buildings. Places, where entry was forbidden due to collapsed ceilings, are now regaining their old appearance.

Often I feel like I appear in places just a minute before fundamental changes. The ‘Extraction’ project is no exception. Some of the photographs in this series have already become archival.

‘Extraction’ is a record of the multilevel experience of living in the shadow of a mine, as well as a visual representation of the impact of the mining industry on the landscape, architecture, air, and people. At the same time, if it were not for coal, the large cities of Upper Silesia would not have had a chance to develop. This is the paradox of place.

About the author:

Michał Łuczak is a photographer, visual artist, and curator. He works mainly with photography and video. He graduated from the Institute of Creative Photography at the University of Silesia in Opava (Czech Republic) and Spanish studies at the University of Silesia in Katowice. Since 2010, Michal has been a member of the Sputnik Photos team. He is also a co-director of the annual Sputnik Photos Mentoring Program, a workshop on documentary photography, and teaches at the Faculty of Arts at the Pedagogical University in Krakow. His recent work focuses on local issues that can also be seen on a global scale: the effects of the coal industry or the economic treatment of forests.