Today there are approximately one million cancer patients in Ukraine, and every year more than 140 new cases are recorded. Social activists are convinced that the Ministry of Health simply ignores people with cancer, and medical institutions that deal with treatment are involved in corruption scandals and deal with complaints about low-quality care. The National Cancer Institute, the main oncological treatment facility, has become a kind of symbol of indifference to oncological patients, despite the fact that the country’s best specialists work there. The Institute was overlooked for money for a necessary laboratory for cancer diagnostics this year, necessary treatment equipment has not been introduced into the facilities for years, and the senior officials change one year after the other following internal investigations. Zaborona explains why the situation today looks like this and how it can be changed.

Everyone is Mistaken

In 2009, the 36-year-old Kiev native Lyudmila Pukhlyak discovered a lump in her chest. She went to her mammologist with the complaint, however, in response, she heard that there was not anything wrong with her chest: it’s sufficient to undergo preventative exams once a year. A year later in the Kiev oncological clinic they said to her, “Why did you come to us so late? Here’s your chart. Go back over there where you’ve been sitting all this time.” The chart read, “Breast Cancer. Stage-III B.” That is, one step away from stage IV, the last stage.

After that, the quest for alternative opinions began. Two histologists said it was cancer; two more said that it wasn’t. They got to the bottom of it at the National Cancer Institute. Two pathologists confirmed the diagnosis, and a chemotherapist prescribed treatment.

“It was easier to tell me where they had done everything correctly than where they had been mistaken. Because everyone had made mistakes, from the regional clinic to the German lab where the postoperative histology had been performed. I underwent treatment at the National Cancer Institute. They operated on me without an exact diagnosis. Once, during chemotherapy, my drugs were diluted in the wrong proportions. The only thing that saved me then was the nurse who, when hooking up the IV, looked at the doctor’s orders and noticed her mistake,” the woman remembers.

Despite the difficulties, Lyudmila still beat cancer, however in 2012, she had a relapse and had to go through everything again. In total, throughout two courses of treatment the woman endured eight operations, radiation therapy, and 18 rounds of chemotherapy. In 2013, she finally heard the word “remission.” But three years later she found out that her mother had cancer. The diagnosis was first made in that very same Kiev regional cancer clinic.

“She was diagnosed with ovarian cancer based on an ultrasound and an examination of fluid from her abdominal cavity. The gynecologic oncologist didn’t look at it even once. No one did an x-ray or a CT scan. They just immediately declared they were starting chemotherapy. But you can’t do that—there are different types of cancer and gene mutations, which determine what the treatment should be. To clarify all of that, you need a number of tests,” explains Lyudmila Pukhlyak.

In order to confirm the diagnosis, Lyudmila went to the National Cancer Institute with her mom. After all, everyone, according to her, goes there “as a last resort.” There was a completely different approach there: an oncologist handled the treatment, and in a week, they were able to go through all the tests to check for metastases, and then to start treatment. Lyudmila Pukhlyak became a kind of “medical manager” for her mom because she had gone through that herself.

Since her first visit to the cancer facility, this woman has regarded “hospital errors as something quite common” and has tried to control the treatment process whenever possible. Also, since then, she has become a social activist. Today Lyudmila Pukhlyak is the co-founder of the charitable foundation “The ‘Lavender’ Aid Center” and the founder of the Internet community “Oncodays” (Onkobudni). She works as a patient advocate.

Far from Ideal and Exemplary

Ideally, the system for detecting cancer and prescribing treatment should look like the following: A person arrives at their appointment with a family physician. He notices a particular problem and sends you either for additional examinations or immediately to a specialized cancer hospital—nowadays a patient can go to any clinic, regardless of their place of residence. In the clinic, the cancer patient gets a chart and is assigned one doctor who also prescribes a set of diagnostic procedures to determine whether there is cancer and, if so, what kind of cancer and so on. When all of the diagnostic results are ready, a council of doctors meets and selects a treatment plan.

Since cancer clinics have signed contracts with Ukraine’s National Health Service, patients are entitled to free care. For example, the packet “Diagnostics and Chemotherapeutic Treatment of Oncological Diseases in Adults and Children” covers consultation, diagnosis, chemotherapy, hormone therapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy (a method of treatment in which drugs only target the tumor cells, not the entire body), pain relief and patient care, and medical rehabilitations in acute conditions.

In practice, everything doesn’t work so smoothly. In the Odessa, Chernihiv, Mykolaiv, and Kirovohrad cancer clinics, money is still required for tests and diagnostics. The material and technical capacities of the clinics do not meet the demands of time: there is not enough equipment or reagents, so conducting all the examinations and going through treatments is often just impossible, explains Lyudmila Pukhlyak. For example, in all of Ukraine the number of linear particle accelerators, which are necessary for radiation therapy, is only 17. Yet, according to the recommendations of the World Health Organization, there should be 170 of them, given the population size. And the amount of PET-CT devices, which are the “gold standard” of cancer diagnosis throughout the world, numbers only four, all of which are in Kiev. Experts say that at least one PET center is needed for every million people.

“Doctors on the ground sometimes ignore medical protocols, like what happened in my mom’s case. Subsequently, (if the patient does not go to check the information) the wrong treatment is prescribed. This entails both a threat to the patient’s life and unnecessary expenses from the budget,” explains Pukhlyak.

Additionally, cancer facilities are regularly involved in corruption scandals. This year, the National Police began criminal proceedings for fraud at the Rivne antitumor center. Journalists found out that employees of the center had been sending patients to purchase films for x-rays from the entrepreneur Yakov Parkhomenko who also works as a radiologist at this medical institution. Parkhomenko was selling more expensive films, and, thanks to that, in 2019 alone he was able to “earn” one and half million hryvnias. By the way, these were not the first criminal proceedings against Parkhomenko. The preliminary investigation had been opened last year—he was suspected of illegally profiting for tens of millions of hryvnias by allegedly taking money from patients for ultrasounds, which were supposed to have been performed for free. However, in that same year, the case was dropped because they had failed to establish that significant damage had been caused. The radiologist is now still working at the antitumor center.

Why Everyone Goes to the Cancer Institute

Almost half of all cancer patients in Ukraine get treated at the National Cancer Institute. Patients from various regions come here either to receive an alternative point of view or for a consultation, or they even come for treatment if they have lost faith in their local doctors. The best specialists of Ukraine work here—candidates and doctors of medical sciences, says the cofounder of “Athena. Women against Cancer” Victoria Romanyuk.

“Going to the National Cancer Institute is not necessary. But historically, it came to be that this is the best cancer institution in Ukraine. And it goes with the stereotypical opinion that they know best in Kiev,” explains Lyudmila Pukhlyak.

According to the medical reform, medical institutions should have become non-profit entities and entered a contract with Ukraine’s NHS, in order to receive money for each patient to provide them with free services. But the institute did not enter into a contract with NHS and, to this day, is subject to Ukraine’s Ministry of Health. Hence, we aren’t talking about any kind of packages of free service for patients here.

Lyudmila Pukhlyak and Victoria Romanyuk claim the Institute functions “as before”—through “charitable” contributions to the cash register or directly into the pockets of the medical personnel. However, the patients’ stories differ. For example, the patient Elena (her name has been changed) in a comment to Zaborona said that she paid for almost everything at the Cancer Institute: for her chart because they did not want to accept one from another city; for radiation therapy; for a place in the Radiosurgery Department. But then there’s Pivonia Tabakar from Rivne who said, on the contrary, that at the Institute, she was able to undergo radiation for free and she didn’t pay for medications or examinations.

Systemic Corruption

Despite its unique and important role for cancer patients in Ukraine, the Cancer Institute is constantly getting into scandals, primarily corruption scandals. In 2015, the publication The Guardian even reported on corruption at the Cancer Institute.

In 2014, the then head of the Ministry of Health Oleg Musiy declared that an investigation at the Cancer Institute had revealed 43 occasions of violations of the law. In particular, patients had to purchase expensive medications even though the state had already paid for them. It was also revealed that a third of the specialists in mammography did not also specialize in oncology, and the specialist who was supposed to be responsible for quality control of medical services was a baker by training. Consequently, the then director of the Institute, Igor Shchepotin, was removed from office. Elena Kolesnik was appointed in his place.

In 2019, the Ministry of Health audited the Cancer Institute and revealed numerous violations. For example, they ascertained that medications had been being purchased haphazardly there. Because of this, there had been delays in delivery. Also, 149 computers, worth 700 thousand hryvnias, had disappeared.

The Director of the Institute, Elena Kolesnik, was removed from her post, and Aleksandr Yatsyna became the acting director in April 2020. Due to the pandemic, he was appointed unrivalled. Yatsyna immediately initiated an internal audit, after which he submitted documents to the prosecutor’s office about filing three criminal proceedings. These included, among other things, forgery of documentation for more than 20 million hryvnias and the signing of unprofitable contracts.

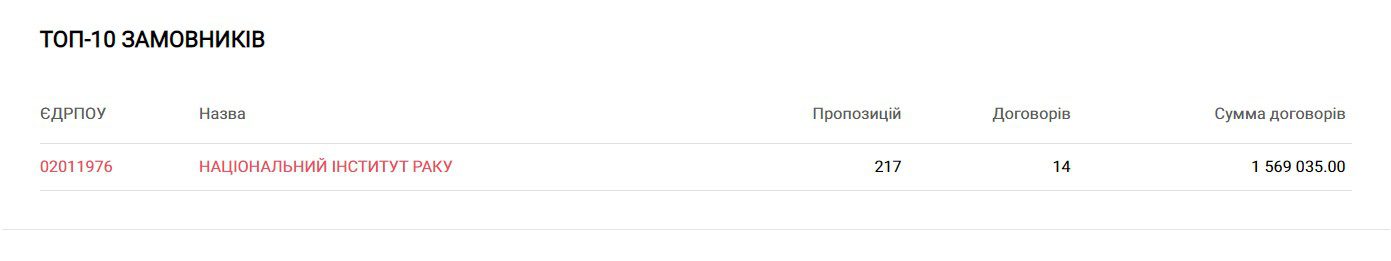

For example, in the winter of 2020, the Institute decided to buy meat to feed the patients. However, in the agreement with the supplier the prices were inflated. The meat supplier was the private entrepreneur Yuri Grigorash. According to Dozorro’s data, he only works with the Cancer Institute and had signed several contracts with the medical institution totaling 1.5 million hryvnias.

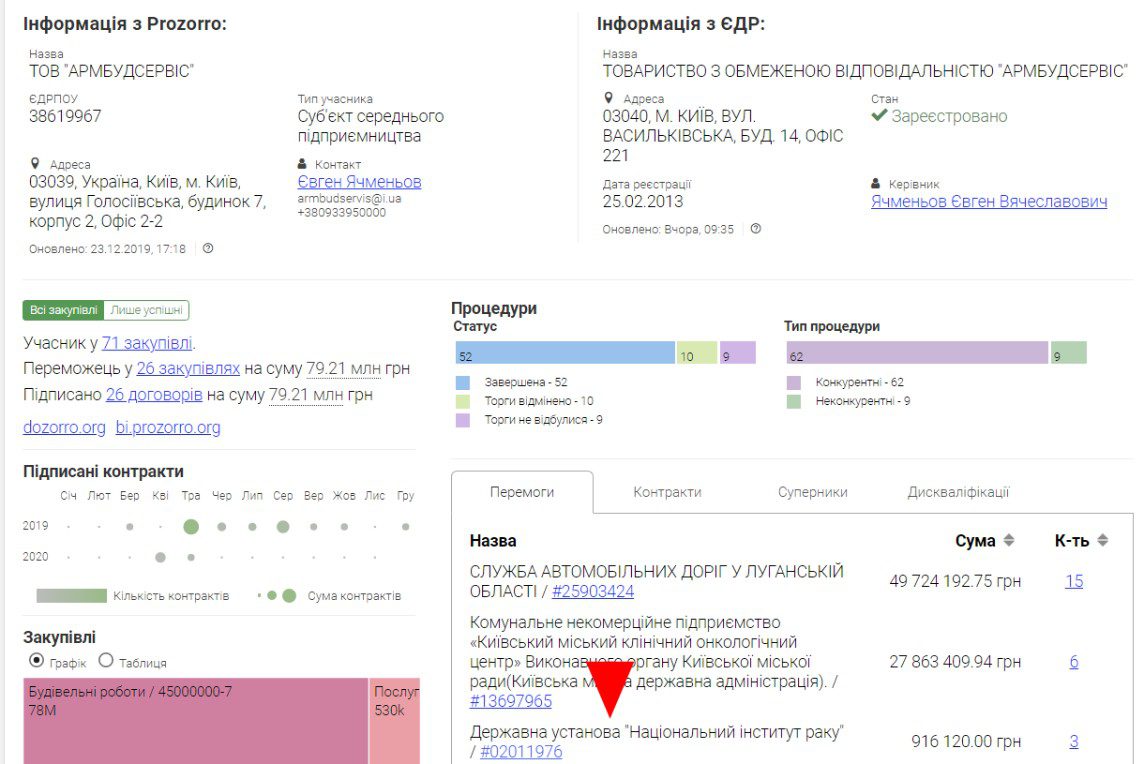

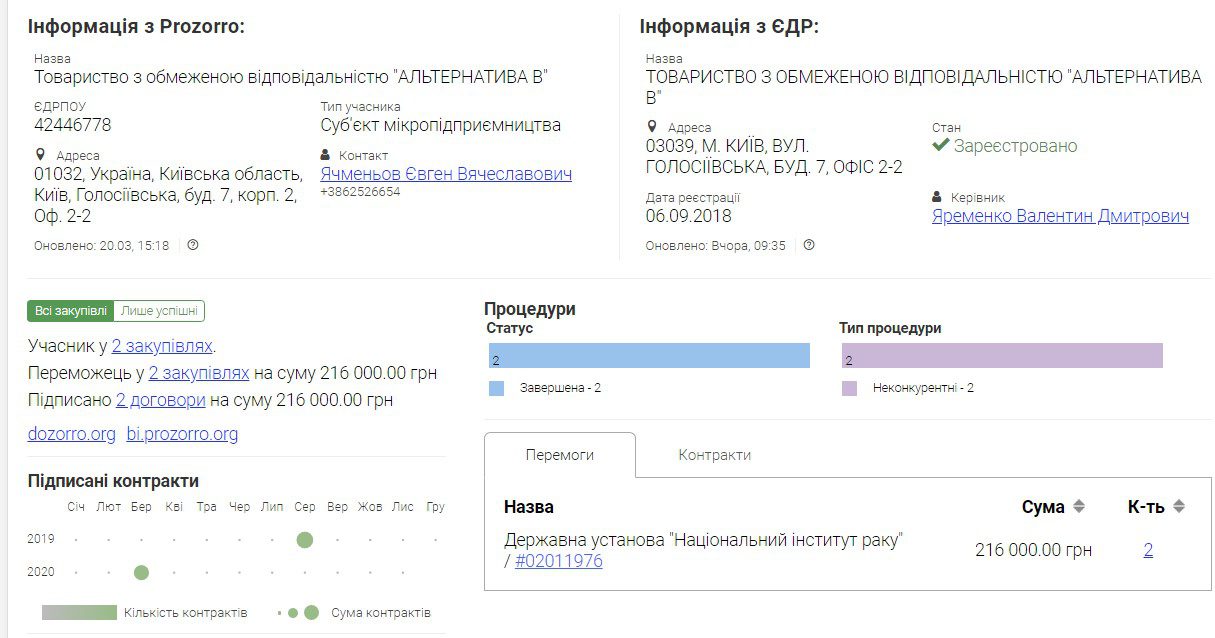

However, already under the directorship of Yatsyna, in October of this year, the Institute purchased nitrile gloves for checkups for almost 2 millions hryvnias, at a price three times higher than the market value. Thus, even the acting director found himself in a corruption scandal. In May, the businessman Evgeny Yachmenev transferred 400 thousand hryvnias to his banking card. He assures that this was a payment for chemotherapy drugs, which were unavailable in Ukraine. But Yatsyna himself says neither Yachmenev nor his relatives have ever been patients at the Cancer Institute. 400 thousand, Yatsyna assures, is the repayment of a loan from the Deputy Director of the Institute, Dmitry Nikitin. Yachmenev is Nikitin’s longtime acquaintance and partner. The firms Yachmenev is associated with have won tenders at the Cancer Institute. And their founder was once listed as Nikitin.

Now criminal proceedings have begun against Aleksandr Yatsyna because of the transfer of 400 thousand hryvnias. 28 organizations require that the Ministry of Health hold an open competition for the post of head of the Institute, but Yatsyna stills remains in this post.

The Institute of Indifference

In October of this year, Aleksandr Yatsyna claimed that in the last ten years “The National Cancer Institute hasn’t received any funding for major construction or the latest equipment from the state.” In fact, funds were allocated, but the equipment itself was never used. It got to the point that the warranty period for some of the equipment expired and now, in order to run it, you need to spend 8 million more hryvnias. In particular this pertains to the linear particle accelerator, which they purchased in 2011. Since they hadn’t started using the device in a timely manner, a line for it formed for a month in advance at the Institute even though cancer patients should receive that kind of treatment within a week. In private clinics the cost of radiation therapy can amount to 100 thousand hryvnias.

In 2019, the then head of the institute, Elena Kolesnik, explained that it was impossible to just run the device like that. The radiation it gave off was dangerous, so special bunkers were built to operate it. In 2011, they purchased this device because they had planned to build a new corpus. However, that didn’t end up happening, so the equipment just lay in a warehouse, Kolesnik claimed.

This year, the Institute did not use 104 million hryvnias, which were meant to be spent on the construction of a modern diagnostic laboratory, on schedule, so these funds were reallocated for renovating roads, a monastery, and a mine. Something similar has happened in previous years—Zaborona has written more on this before.

“This laboratory was important because what form of cancer a person has would be determined in it. Previously, treatment was like shooting sparrows with a cannon: they determined that a person had, for example, breast cancer and then sent them to chemotherapy. They don’t do that anymore. Depending on the type of tumor, one or another treatment protocol is used, which determines the success of the treatment, whether there will be a relapse, and the cost of treatment. Nowadays, patients mostly go to private clinics for similar treatments because there is no state medical institution that would do research at the level at which it’s done in Germany, Turkey, Israel, or even in Russia,” says Lyudmila Pukhlyak.

Just how the Cancer Institute missed out on this money can be explained with the words of the Minister of Health, Maksim Stepanov: “it was out of reach.” As Anna Uzlova, the cofounder of the charitable organization Inspiration Family, mentioned in the comments of Zaborona, we have a situation when there are funds for treating cancer patients, but because of mishandlings they don’t reach those who need them most.

Zaborona tried to clarify with the Cancer Institute how much money the institution had received from the government in the span of ten years for updating equipment and repairing buildings, but we did not receive an answer. Also, there are unanswered questions about reconstruction and construction projects that were started and abandoned, the handling of complaints from patients about the staff, the hiring of employees, and so on.

Unnoticed Problems

Throughout all of the years of independence in Ukraine, cancer patients’ problems have not been noticed, and the funds they needed were constantly stolen or written off for something “more urgent,” says Lyudmila Pukhlyak, an activist of “The ‘Lavender’ Aid Center.” According to her, the reason for the current situation is simple. During the treatment period, cancer patients don’t have time to deal with corruption and write letters to the country’s leadership with their demands. Those who are faced with cancer, says Pukhlyak, think about how to survive and where to get money for another round of treatment. And if they do manage to overcome the disease, they want to forget about it. Those who earn an above-average salary are treated in private clinics and simply do not face what patients of municipal institutions face, adds Lyudmila Pukhlyak. And only a few out of the thousands of patients become activists.

Pukhlyak suggests that doctors themselves could have reported problems. However, it wasn’t necessary for them: people would still come to them for help, and some simply compensated for the low salary with bribes.

The National Strategy for the Fight against Cancer could solve the cancer patients’ problems. Its development is underway right now. However, not one of the patient organizations defending the rights of adults with cancer were included in the working group. It was unofficially reported that activists would be able to join the discussion later, explains Pukhlyak. In her opinion, that’s not right, since only patients who have experienced cancer know what they need.

Translated by Taylor Wilson from Respond Crisis Translation