On April 13, 2020, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy introduced a bill to Parliament that would dissolve the Kyiv District Administrative Court. The Court, run by head judge Pavlo Vovk, has long become a byword for judicial corruption in the country, and Pavlo Vovk is one of Ukraine’s foremost corruptioneers in the post-Maidan era. However, he’s largely been untouchable, despite the scandals and evidence against him. Zaborona’s Romeo Kokriatski takes a look at Vovk’s history, his scandals, and how he’s managed to avoid prison this long – and if that may change.

Pavlo Vovk, nee Zontov, has had a spectacular career in Ukraine. He’s blocked decommunization initiatives, defended fraud, and interfered with the country’s health system. He’s grown quite wealthy – not to mention influential – in the process, and he’s managed to dodge every single corruption allegation and attack against the court he heads for decades. Now, however, he, and his court, may finally be running out of time: Zelenskyy, long seen as weak on corruption issues due to his politicized pick for Prosecutor-General, Irina Venediktova, has finally moved forward with a bill to liquidate a court often called the most corrupt in Ukraine – among heavy competition.

Born in Kramatorsk, in northern Ukraine, Vovk attended law school in Kharkiv. It was there he met his wife and took her surname, an uncommon practice in Ukraine, with that rationale being that his original surname wasn’t Ukrainian enough. He graduated with honors in 2000, before moving to Kyiv to work in the Kyiv regional prosecutor’s office. He quickly rose through the ranks, first as an investigator, then as the senior assistant to the prosecutor in the statistics department.

Meeting Kivalov

His tale of corruption began thus, four years later. This was when he met Serhii Kivalov, the man who would shape Vovk’s life, and his predilections, for years to come. Kivalov, himself a notorious figure in Ukrainian politics, was a close associate of runaway Ukrainian ex-president Viktor Yanukovych, and Vovk would do much to ensure Yanukovych’s rule. When Kivalov and Vovk met, Kivalov was the the head of the High Council of Justice and the head of Ukraine’s Central Election Commission, and was likely influential in moving Vovk from then, a mid-level prosecutor in Kyiv, to the head of Kyiv’s territorial election commission – during the infamous 2004 election that would later lead to Ukraine’s Orange Revolution. Kivalov, widely known across the country as one of the central actors in the plot to falsify the election in favor of Yanukovych, would soon reward Vovk for his participation in the scheme.

Serhii Kivalov. Photo: Volodymyr Gontar / UNIAN

Post-election, Vovk quit his job at the territorial electoral commission, and instead went into private practice with a company called RADA – with the hefty title of Deputy General Director. That role can be seen as Vovk’s reward – RADA’s general director at the time was a woman known as Iryna Orekhova, who had previously been one of Kivalov’s assistants, and her husband – the head prosecutor at Kyiv’s Shevchenko district prosecutor’s office.

Vovk didn’t stay at Rada long – the following year, in 2006, Vovk joined Kivalov’s team in parliament as an MP’s assistant, and a year after that, made yet another job change – this time to judge. Allegedly, his upgrade – from erstwhile prosecutor, electoral commission head, and private lawyer, to judge – was done with the help of Lydia Izovitova, the head of the High Council of Justice at the time, and is said to be close to pro-Russian oligarch and media mogul Viktor Medvechuk.

Joining OASK

It wasn’t until 2009 that Vovk really found his footing, however, at the position that would center himself as the spider in Ukraine’s web of corruption – head judge of the Kyiv District Administrative Court (OASK, as commonly abbreviated after the Ukrainian name). The vote to appoint him as head judge, by the way, was initiated by none other than Serhii Kivalov. Vovk, importantly, also became a member of the High Qualification Commission of Judges – a body that, as its name suggestions, weighs judicial qualification – at the same time.

This wasn’t the end of Vovk’s career growth, however – he had one more upwards move to make. In 2010, Vovk was granted a lifetime posting as head judge of OASK. Vovk no longer had anything to worry about, and he was swift in making use of the freedom that lifetime tenure afforded him. Corrupt rulings began raining down from OASK, cementing its reputation as the court to file in if you had some corrupt dealings you wanted legalized. For example, that same year in 2010, Vovk unilaterally cancelled broadcast spectrum grants awarded to two channels, TV-i and 5-Kanal – based on a lawsuit filed by the Inter TV channel, which was seen to hold a stringently pro-Russian position.

His cooperation with Viktor Yanukovych developed closely in the years ahead, with Vovk’s court issuing a number of at best ‘questionable’ rulings – first in favor of a complaint filed by MPs from the then-legal Communist Party of Ukraine about removing protestors from under Parliament, then cancelling millions of hryvnia owed in taxes by the shell corporation that owned Yanukovych’s residence, Mezhyhirya, in addition to many other such rulings – always in favor of the interests of Kivalov or Yanukovych, or simply in the interests of the monied.

Viktor Yanukovych and Serhii Kivalov (back). Photo: Andriy Mosienko / Party of Regions Press Office / UNIAN

Justifying Berkut Violence

This predilection of ignoring legal norms in favor of corruption reached its head during the Euromaidan protests, where Vovk’s court was instrumental in the riot police (Berkut) justifications for violent force in dispersing the protestors. In 2013, a judge from Vovk’s court, Viktor Danylyshn, was asked by the Kyiv city authorities about the legality of setting up kiosks, tents, and other typical features of a stationary protest, on the Maidan, Kyiv’s central square. Danylyshn ruled in favor of banning the practice, and the Berkut used this ruling to allow themselves to violently disperse the protestors. For his help in repressing the Maidan, Danylyshn was granted a state-owned apartment – soon privatized and sold for approximately $325,000.

Following the Maidan and Yanukovych’s self-exile to Russia, Vovk and his judges managed to avoid immediate punitive effects. The country became subsumed with discussions of ‘lustration’, the process by which corrupt judges would be removed from power around the country. Unfortunately, lustration proved to be only a good idea. Instead, Vovk’s court managed to grow their influence further, and continue the practice of selling rulings for cash or power. This process began even as the protest camps still remained on the Maidan, with Vovk receiving, in 2014, a ‘ceremonial weapon’ from Ukrainian Interior Minister Arsen Avakov. Vovk’s association with Avakov may have assisted in a favorable ruling for a company said to be owned by Avakov’s son under investigation for money laundering – that won tenders from the Ministry of Internal Affairs despite the charges, in 2017.

Arsen Avakov. Photo: Oleksandr Sinitsya / UNIAN

A Byword for Scandal

Vovk’s name, and his court, were at this point popularly known for their corruption, and it was hard to go a week without seeing yet another scandalous headline involving him or his judges. Far from dampening Vovk’s enthusiasm for bribe-taking, his avoidance of any pushback for his involvement in Yanukovych’s administration or his culpability in the Maidan, he seemed to be emboldened. Some highlights of the next few years included killing then-president Petro Poroshenko’s reform plans for the Supreme Court in 2016 (Vovk applied for a position on the planned reformed court, before outside experts noticed that many of the judges who’d applied were falsifying their scores, and Vovk personally had help from High Qualification Commission member Yuri Titov, the godfather to one of Serhii Kivalov’s children.)

It wasn’t long before the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) set Vovk in their sights – as a core enabler of official corruption for over a decade, he would come to be NABU’s white whale, and the conflict between himself and NABU stretches on to this day. One early battle involved an investigation into Vovk’s personal properties. Surprisingly, it turned out that Vovk had none – unsurprisingly, in a common Ukrainian tactic, the properties actually belonged to Vovk’s ‘ex’-wife, with whom he still lived with.

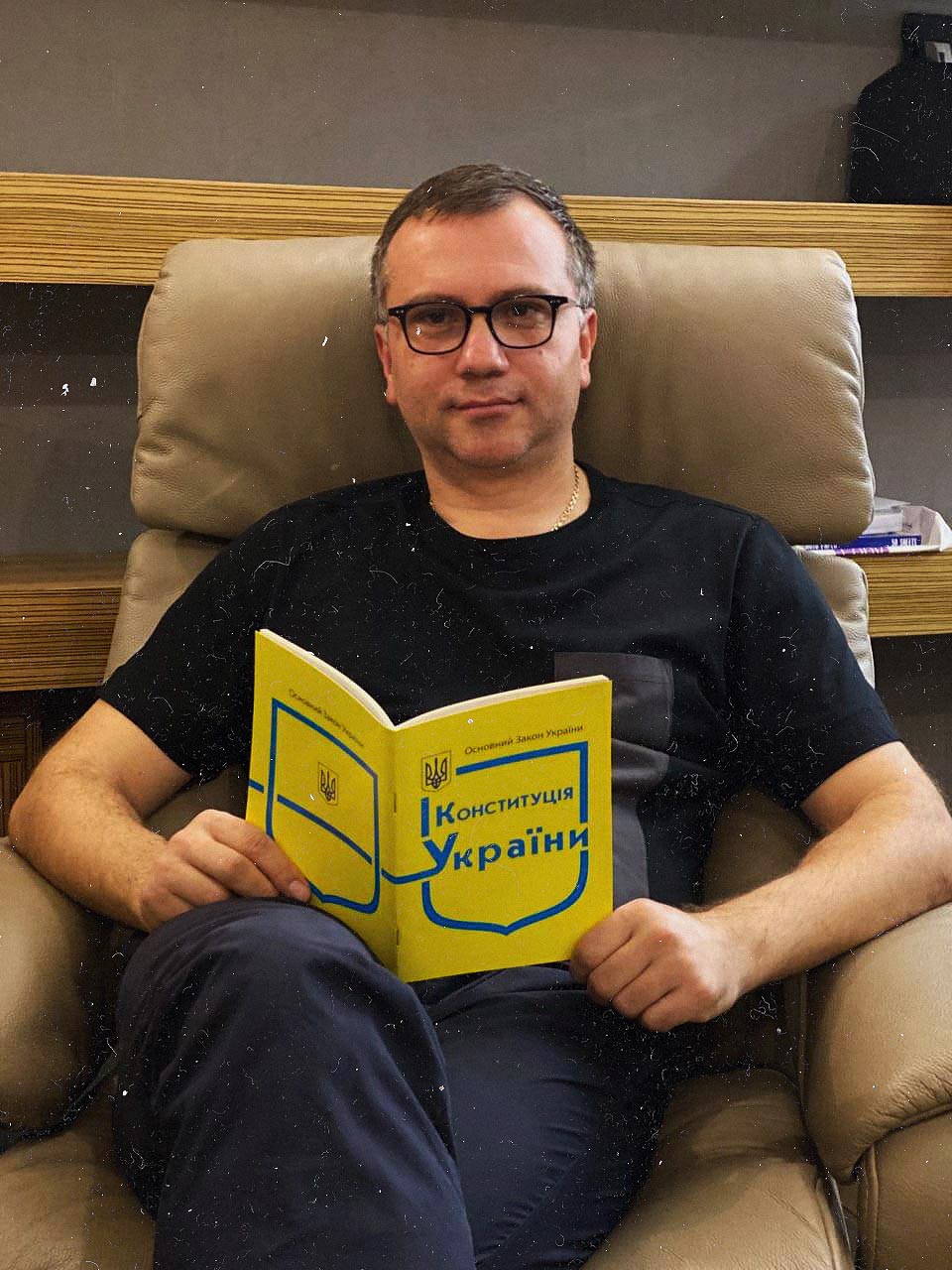

Павло Вовк / Facebook

Dodging yet more bullets, Vovk managed to remove OASK from a list of courts to be liquidated as part of the legal reforms in 2017 after Vovk recused himself from the competitive selections for Supreme Court justices. Yet this relationship with Poroshenko would seemingly splinter a few years later – in 2019, Vovk’s court cancelled the decision to nationalize Privatbank, formerly owned by oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky before a $5.5 billion fraud was discovered at the country’s largest bank. His court also issued a number of disputed ruling preventing Poroshenko from appointing various heads of departments critical for the reform efforts, including the tax service and customs.

Meanwhile, NABU continued with their efforts to implicate Vovk in something – anything – releasing numerous recordings implicating Vovk in schemes such as conspiring to access a journalist’s personal information, agreements with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, banning Poroshenko-era civil servants and officials from travelling outside of the country. Nothing seemed to stick.

That same year, 2019, with Poroshenko’s administration coming to a close, Vovk began his attempts at currying favor with what-would-soon be the incoming Volodymyr Zelenskyy administration, meeting with highly-placed members of Zelenskyy’s campaign team, such as Zelenskyy’s then-chief-of-staff Andriy Bohdan and soon-to-be Prosecutor-General Ruslan Riaboshapka. He continued to be a staple of Ukrainian headlines with controversial and often obviously corrupt rulings, such as the reinstatement of Yanukovych-era official despite their charges or dismissals for corruption based on flimsy pretexts.

Павло Вовк / Facebook

Accountability’s Just a Phrase

Even recently, Vovk’s name, and his court, has cropped up in stories about lawyers being arrested with bribe money intended for OASK (carrying $3.6 million USD in cash, along with 40,000 euros, 20,000 GBP, 230,000 UAH, and 100 Israeli shekels.) And NABU is still doggedly trying to stick Vovk with anything, revealing recently that Yuriy Zontov, Vovk’s brother and an employee of Ukraine’s foreign intelligence service, took a $100,000 bribe to influence a court ruling.

These efforts have culminated President Zelensky, on April 13, introducing a bill to ‘urgently’ liquidate OASK – a move unanimously supported by every one of Ukraine’s international partners, the business community, and likely, most Ukrainians sick of the prevalent corruption that makes Ukraine’s legal system seem less like an arbiter of justice and more a marketplace for business disputes. Yet Vovk has shown over the years an uncanny ability to avoid any accountability for his court or his own actions, and has screamed of ‘political interference in the judicial system’ whenever corruption allegations are brought up.

Law enforcement officers near the Kyiv District Administrative Court. Photo: Viktor Kovalchuk / UNIAN

At the same time, it is clear that dealing with Pavlo Vovk’s proven corruption, based on both recorded decisions and leaks and investigations by NABU, will become a necessity for any reform-minded administration – especially one reliant on Western grants, loans, and aid. As long as OASK and Pavlo Vovk’s positions are secure, Ukraine can never, and will never, be able to truly free itself from its tarnished reputation and the yoke of grand corruption.