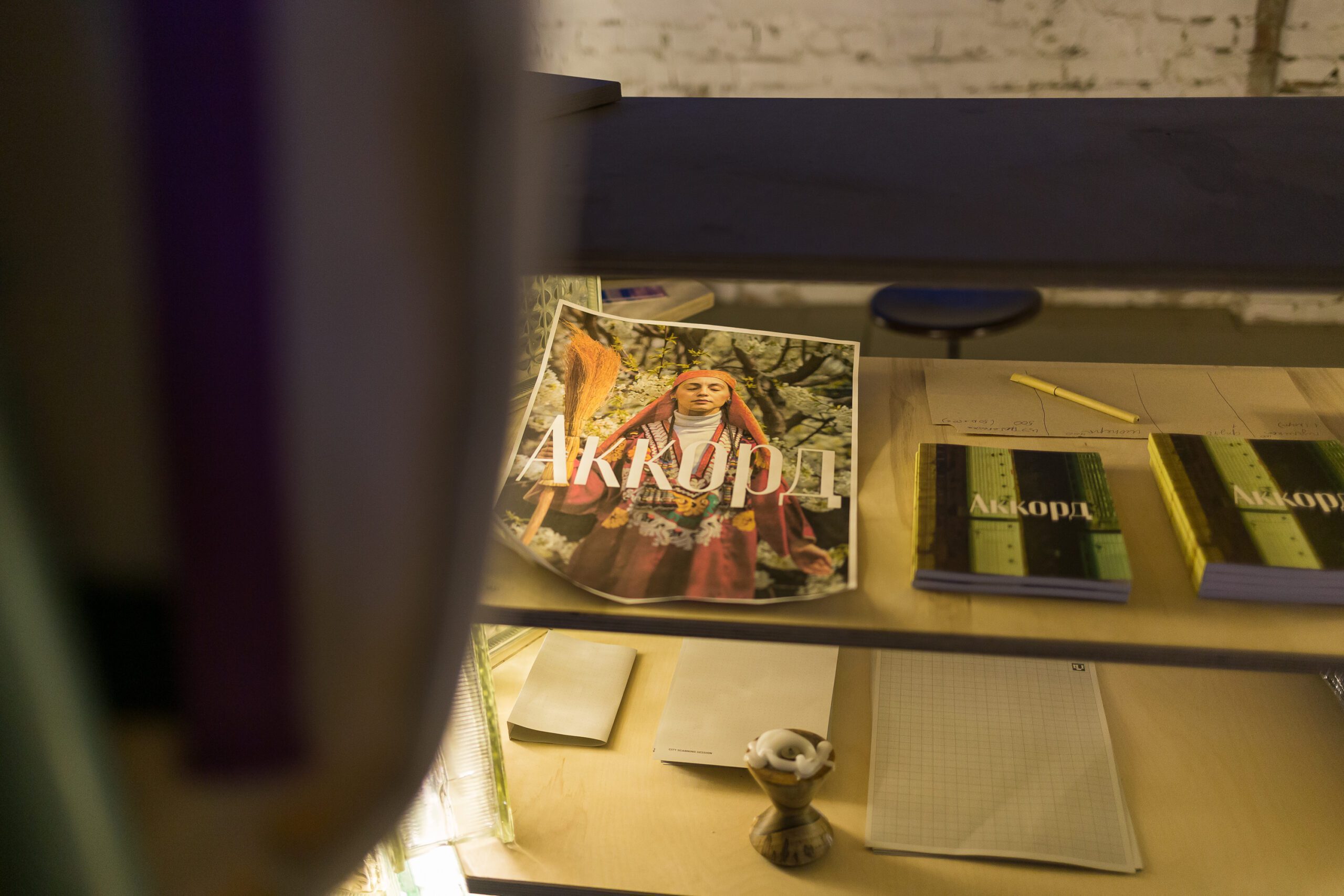

The Kuduk Cultural Center arrived in Ukraine with a tour from Kyrgyzstan in the autumn of 2021. Its experimental performance “Accord” (en. “Chord”) is the story of the civil war in Tajikistan, which took lives of at least 100 thousand people in five years. The tour was organized by the Ukrainian youth organization “STAN”, whose founder Yaroslav Minkin was amazed by the way Asian artists reflect complex pages of history through art. Performances were held in a number of cities in Ukraine as part of the Peace Day events. The stage director of “Accord” Diana Rakhmanova has not seen the war with her own eyes, but she has been facing its echoes all of her life. She told the editor of Zaborona Maria Pedorenko about how close the history of Tajikistan turned out to be to the Ukrainian audience and why bread played a big role in it.

Events for the Peace Day are held by the Youth Organization “STAN” with the support of the US Agency for International Development USAID.

The hall is warm: the heat comes from the stage. There is an oven between two tables in the spotlight. Looking like a barrel all covered with shiny tile patterns, she attracts audience’s attention. Today she is one of the main characters, a guy named Talgat keeps bustling around her.

He wears a checkered apron around the waist, and a white bandage around the short-haired head. He rushes from one table to another: first he kneads a huge lump of soft dough, then divides it into smaller pieces and turns each into small tortillas with thick sides. He covers them with raw egg, then sprinkles with a pinch of black sesame. One by one, the tortillas go into the oven. She is all of white, red and blue mosaic on the outside. On the inside, she is the color of a tanned body, and the patterns are the prints of last baking.

After a few minutes, the smell of fresh bread begins to disperse through the hall along with the warmth from the oven. Very soon there will be a queue for it, as if in times of depression. But for now, a man’s voice echoes against the walls.

“There is no your life, no my life. The destinies are different, but life is only one. It is an endless existence, in which there are stories. Your story, my story,” he says.

This person is not in the hall. His speech is dictated by the speakers. And he is not alone on the record. A woman’s voice sometimes gets wedged into a long, deep monologue. Sometimes with short questions. Sometimes – with reasoning. And in the finale, the whole audience bursts in tears.

“That’s amazing. Thank you for your openness,” he responds to tears.

Talgat bows. The light goes out. People in the hall begin to applaud.

The War behind the High Wall

When the war began, Diana Rakhmanova was three years old.

The USSR collapse brought independence and power struggle to Tajikistan. The struggle so fierce that it quickly turned into an armed conflict. Supporters of the former communist elite went against the opposition — the national democratic Islamic forces. The most violent clashes took place in 1992-1993. At that time, the death toll reached 60 thousand people. And by the end of civil war in 1997, this figure had grown to 100 thousand, according to official data.

Little Diana did not see the war with her own eyes. She spent almost all these five years behind the high walls of a Dushanbe orphanage. The girl’s mother decided to leave her there for a while — the new husband accepted a child born not from him with a cold shoulder, and the woman was afraid she would be left alone with her daughter in the middle of war. The plan was to take Diana home at a safer time. But life turned out differently.

“I’m 31 now and I’m still learning to love, because I, probably, didn’t get enough parental warmth as a child, ” she says.

“Fear, hopelessness and confusion,” she says of her associations now.

In the late 90s, ten-year-old Diana got into a new family. When the future foster parents decided to take the girl, her mother agreed. But she did not disappear from Diana’s life — as an adult Diana continues to communicate with her mother and with her new family.

Although very young Diana did not feel the presence of war in her life, the imprint of the conflict began to manifest itself more and more with age. “Now any problem that exists in the country has some reference to these events,” she explains. She also notes that the topic of war remains taboo for Tajikistan decades later.

Why so? What are people afraid of? Why do they confidently stick to stability, even when it does more harm than good? And how to find support in this hopelessness? All these questions have been bothering Diana Rakhmanova for a long time. The search for answers led the young artist to “Accord” — a non-classical theatrical production, where the history of the civil war is reflected not only in the words of people, but also in the process of baking bread. Literally.

History in Music and Bread

Tandoor — the barrel-shaped oven in the center of the performance — is a very common thing for Asian countries. Such ovens are installed in private homes, in small bakeries or hypermarkets. And the tandoor bread itself is a symbol of the national product for many countries.

In Tajikistan, tandoor appeared just during the civil war: “People ground practically black flour, the remains of some wheat and baked bread from it,” says Diana. The shops were empty. There were long queues for bread, the most basic product, as it seems. According to Rakhmanova, in Tajikistan bread was used instead of money to pay salaries to artists. There was nothing else to pay with.

“For me, it [baking tandoor bread on stage] was an opportunity to show something ordinary that passes by every day, which we do not pay attention to. Although baking tandoor bread for me is an art as well, ” says Diana.

At first, a professional tandoor baker performed in the play, but over time he was replaced by actor Talgat Berikov. He almost didn’t have to learn for the role.

“What’s so difficult? laughing, says Ilya Karimdzhanov, a member of the “Accord” technical team. – Our actor loves to cook, he bakes bread at home. We called the tandoor baker again, he showed us what and how to do, gave us a recipe and that was it. Nothing new, except for a couple of technical points — how to properly stuff the bread into the tandoor so that it sticks, and how to remove it correctly.”

Outside the performance, the cooking process lasts even faster. On stage, Talgat adjusts baking to the timing of the conversation, which sounds parallel to his work. The disembodied voice of “Accord” belongs to Daler Nazarov, a legend of the Tajikistan stage.

The 60-year-old musician and songwriter appeared closer to the finale of the performance. Diana Rakhmanova was looking for answers to her questions in conversations with people, as well. All of them are directly related to art: artists, actors, musicians, and many more. All that was missing was a person without whom it is impossible to imagine the culture of Tajikistan. Diana managed to reach out to him through acquaintances. When Daler Nazarov called, she was just getting ready for a flight. “If you personally need it, and your soul wants to talk to me, I’m open,” he said, and Rakhmanova immediately went to the meeting.

“He doesn’t communicate with everyone and doesn’t like standard interviews very much — how many CDs did you write, for which films did you make music? Probably, he wants to communicate more on free topics, he always goes into more philosophical concepts,” explains Diana Rakhmanova. — When I came to him, I realized that this is an ordinary person who does not think of himself as a star at all, does not take all the laurels for himself, although he has every right to do so. We talked with him very freely, he turned out to be the simplest person.”

While with other heroes of her conversations the artist touched directly on the events of the civil war, the conversation with Daler Nazarov flowed from war to coronavirus, from death to love, from inconsolability to happiness.

“I live in my Dushanbe. It lives in my heart. But each generation comes and builds it in its own way. Once there were slums, then people with more progressive views came, started building, then others came and built something else. Now there is an opportunity for another generation to express themselves. But the spirit of this city does not depend on buildings. It doesn’t depend on anything,” Nazarov says at one point.

Diana Rakhmanova has not yet managed to show “Accord” in her native city Dushanbe. She lives in Kyrgyzstan since her university days. The premiere of a play about the civil war in Tajikistan was also held at Bishkek cultural center “Kuduk”, where Rakhmanova works. A few days before the first show — on April 28, 2021 – disturbing news began to arrive from the border between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Shots were fired at the disputed section of the border — the servicemen of both countries opened fire after the conflict due to the installation of video cameras on the poles of power lines. In the next four days, 55 people were killed, and more than 33 thousand people were evacuated from the combat area.

Diana’s friends were worried that her play could cause a negative reaction. A former colleague wrote to her in private messages that the performance was too off topic. But the artist did not cancel anything, and began the premiere with a minute of silence in honor of the victims: “This situation showed that the war in fact is very real, it is now and here, and not somewhere far away.”

The border between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan has been closed for the last six months and it is unclear when the situation may change. But Diana Rakhmanova says that she still wants to show her performance to people who have personally seen the war in their country. This is her plan for the future. But for now, “Accord” has found its audience in Ukraine, where the end of the war is yet to be seen.

Fix the “deaf phone”

“It happened accidentally,” says Diana about the tour in Ukraine.

In 2019, at a leadership conference in Kiev, she met Yaroslav Minkin, the founder of the STAN youth organization, which has been gathering people of culture, human rights, education and media for more than 20 years.

“Yaroslav came to us [in Kyrgyzstan] two years ago. He was very interested in the fact that we are rethinking complex events in the country through art. I told him that I was planning to do my research [on the civil war], and, I think, he got very excited about it. And when the premiere took place, he said that it would be very cool if we came, because the topic is very important and complex,” recalls Rakhmanova.

On September 13, 2021, the Accord team arrived in Ukraine. The tour route was made so as to see different parts of the country and at the same time show the performance in those regions where almost no one arrives. So, in addition to Zaporizhzhia and Ivano-Frankivsk, the performance was also shown in Nova Kakhovka (Kherson region), Bilovods’k (Lugansk region), Bat’ovo (Zakarpatye)- six localities in total.

“Diana was worried that at the first performance people would just go away and say they didn’t understand anything. But she calmed down after performance in Ivano-Frankivsk. And I had that thought as well until it all started. – tells Ilya Karimdzhanov. — I was impressed by how this performance is welcomed in Ukraine. Despite the fact that we are from another world – Asia is a slightly different culture, to say the least -, everyone was very interested. It seems to me no one expected everything to turn out that well. ”

In every city and village there were discussions. The audience could discuss with the authors the thoughts and feelings that arose in them after seeing “Accord”. They talked about the war, about the people they lost, about migration and integration. Someone thus found an opportunity to speak out, others did not hide their tears. Diana Rakhmanova says that during the dialogues there was a lot of pain, but there was also a lot of love: “After the show, people came to us to hug, kiss, wanted to say something kind. And for me it was very valuable. I am not so bold to do this, here [in Asia] we have a different region, and different people. But I felt a great desire to hug everyone, too.”

In 2014, Diana already visited Ukraine with a team of journalists from different editorial offices of Kyrgyzstan. They came to Kiev to see with their own eyes what happened here during the Revolution of Dignity and after it. According to Rakhmanova, in Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the TV channels covered events in Ukraine through the prism of Russian politics.

“No matter how sad it is; people here consider Russia as their brotherly people. While watching football, they shout “our team” if Russians play. This is a very strange logic that still exists, especially among the older generation. There is a lot of propaganda coming from Russian state TV channels — and people here watch only them. There is a big information war going on. When you watch television here, there are no alternatives,” she explains.

Journalists from Kyrgyzstan visited both sides of the war in eastern Ukraine at that time. And they encountered stereotypes about Kiev or Donbass everywhere: “Fortunately, we could see what is exaggerated and what is more or less true.”

When Rakhmanova arrived in Ukraine in 2021, she understood how sensitive the topic of reconciliation remains for people. But it was very important for her to explain that this is not about reconciliation with Russia, but about peace within the country – between western and eastern Ukraine.

“It’s like a deaf phone — everyone has their own truth and no one hears each other. In such processes, I do not speak for any of the parties, because everything is much more complicated. If it was obvious who was right and who was to blame, then there would be no problems after all,” says Rakhmanova.

Accord’s tour ended on October 2. According to Diana, the performance showed a new side to her thanks to this journey. It showed how theater can be a great peacemaking tool – for building dialogues between people as well, which are so necessary today. But these were not the only conclusions she made for herself while working on the performance.

Love is the answer

“The people of Kyrgyzstan, where I live, have been nomadic since ancient times. The fact that revolutions happen there very often is also due to the fact that historically Kyrgyzstan does not hold on to one permanent thing. If we don’t like something, we leave and settle in another place,” says Diana Rakhmanova. – Tajiks are, on the contrary, settled people. Stability is important to them; they are completely different in temperament. Maybe that’s why they like to praise everything so much and don’t like to fight so much.”

According to the artist, the history of the people is also connected with the fact that the modern art of Tajikistan is very calm – far from aggression or provocations. For Diana, it was important to make her production experimental, without showing the civil war through the actors’ play: “When we watch classical performances, a lot remains behind the screen. There is only a history, a representation of events. The reflections, which, I think, are also very important, are, unfortunately, left behind the scenes.”

Daler Nazarov’s words: “If you didn’t have love, you wouldn’t have come here. Love for everything. The interest with which you came here is vital for me. We’ll talk to each other, you’ll go there, and I’ll go there. That’s it. The story seems to be over. But this alive, real moment — it is priceless.”

Love is as well Diana’s answer to what helps to find support during an endless war.

“Now I feel like this: if you love, then there is an “Accord” in you — harmony with what is happening, even with the most terrible things – war and its consequences -, and especially with what you cannot change. It is important for me to love and convey these feelings to those around me,” she admits.

“Accord” is about music that characterizes the Tajik people and their lyricism. But at the same time, it’s about bread: “Ak” in Kyrgyz means white, “Cord” in Tajik means flour.

While actor Talgat kneads dough on stage, rolls out bread and removes it hot from the walls of the tandoor, musician Daler Nazarov says that we all live in an endless existence, and difficulties await us until people realize that we are all one: “Bad, good, stupid, smart, beautiful – we all form a single ornament, each element of which cannot be excluded.”