More and more people around the world are using artificial intelligence to create images, including for disinformation, distortion of reality, and influence on vulnerable people. The more AI networks develop, the more challenges society faces. Zaborona’s editor-in-chief Kateryna Serhatskova talked to Fred Ritchin, a researcher of the impact of artificial intelligence on visual culture, about whether it is ethical to create an image of a person who is allegedly a victim of a known disaster (but who never actually existed), and how fake photos erode trust in photojournalism.

Fred Ritchin is a writer, teacher, editor, and curator. He has written three books on the future of the image: In Our Own Image (1990), After Photography (2008), and Bending the Frame (2013). He is Dean Emeritus of the International Center of Photography and teaches at various institutions, focusing on image strategies for human rights.

Fred Ritchin. New York, October 2022. Photo taken during a talk about the Ukrainian War Photo Archive. Photo: Kateryna Serhatskova / Zaborona

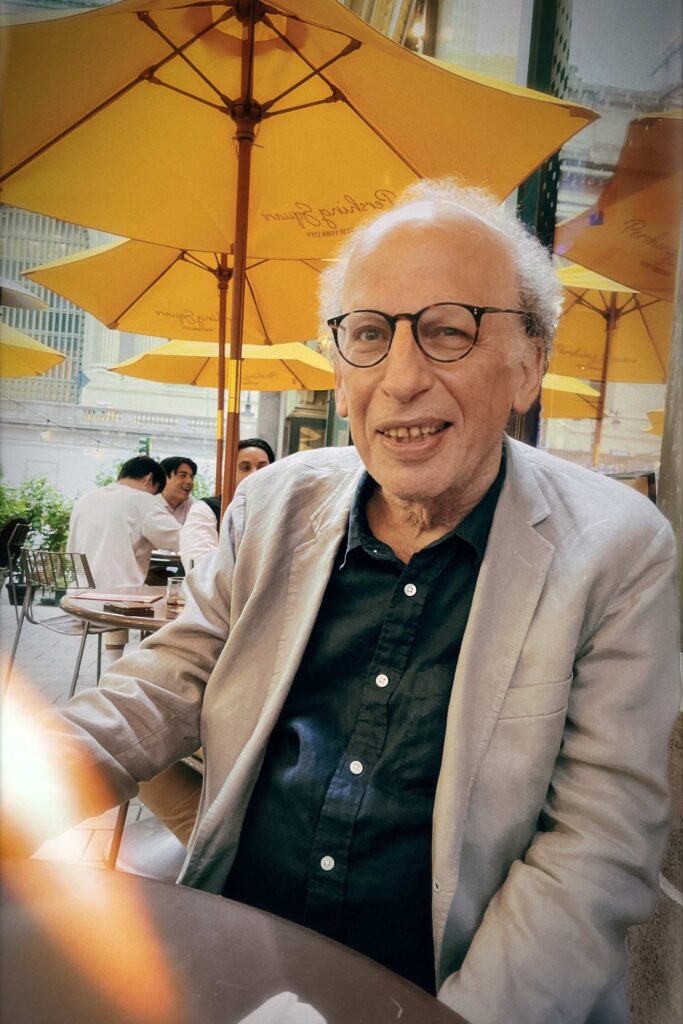

Recently, the Ukrainian parliament tweeted about the tragedy in Dnipro, where Russians shelled a residential building. The information was illustrated with a picture created by artificial intelligence. It showed a crying child and a destroyed building behind it. In 20 minutes, the tweet was deleted, as users began to complain that it was unethical. A lot of similar things have been happening all over the world since artificial intelligence mechanisms started spreading, but this was probably the first case involving official bodies that I’ve seen. What exactly is unethical here, in your opinion?

The problem is that you open the door for anyone who does this [image generation]. You can take happy Ukrainian children or unhappy children, or someone completely different — Russians, for example. I think that when you use AI, you have to be very careful, for example, if you want to say that AI predicts that the war will last for another two years, then that’s something you have to look at and then contextualize. For example, in the case of climate change, we can predict what a city or something will look like in 5 years if we don’t change anything. But as soon as you open up artificial intelligence, anyone can do what they want — it’s very easy, a 12-year-old can do it, and it’s almost free. And they put it on social media.

Screenshot from a tweet by the Verkhovna Rada

I think it’s very dangerous [for officials] to start using AI in this way. If you want to make a memorial and show it to people, you need to look for other ways to do it. There are many examples: a plane crash, when you show the things of the people who died, what they left behind, for example, their shoes. You don’t have to show a person, but the introduction of AI, in my opinion, opens up a war of artificial intelligence, where everyone shows everything until they start to lose track of what is true and what is not, and the war becomes an abstraction.

Do you think we can get to the point where no one will rely on images anymore?

Yes, I am writing a book about this, and I think a lot about what we can do about it. One of the ideas is reliable sources. Any writer can say anything, but when it comes from the Associated Press, the NYTimes, a reliable source, there is an intention to believe. I think we have to be very careful with credible sources, which means that photographers should publish what they are absolutely sure about. Just like any other journalist, they have to understand what they are doing and keep people’s trust. You can’t just believe in a photo because it looks like a photo.

It’s gone viral: people are systematically using artificial intelligence [to generate images]. Do you know of any opportunities to do something about it?

I think we need to make it so that people can’t retouch photos and can’t use Photoshop on a massive scale. So, a link to the photographer’s website works, because there you can make sure that this particular person is not using AI to create photos. Also, in this case, it is important not to use just one image — it is better to use several or even a video, and maybe use a personal profile to show that this is you and you were there and filmed the war for several months, and this is your diary and a first-person story. Photojournalism is something that comes from the first person. Use words, audio. We live in a multimedia environment.

When I interview a person, I provide the text but put a link where the reader can see the person on video. And then you start to believe in the reality of the conversation. It is important to be separated from artificial intelligence and people who use Photoshop all the time. Why should anyone believe me as a writer? It’s just words. But I have a reputation, and I have to maintain it.

Do you think there should be a new social contract regarding images and their use?

I think we need to start individually. If I’m a photographer, you can click on my name and see my code of photographic ethics [which says that] I don’t set up anything, I don’t impose anything on people, I don’t pretend that something else is happening. I am responsible for my images. It’s easy to do. You can write your own code of photo ethics in two sentences. I’m a photojournalist, and all my photos are interpretations, but they are also documentation of reality, and I’m not playing with it, I’ve been covering it for six months or seven or whatever. The camera is not enough anymore, [you can no longer consider an image authentic] just because it was taken with a camera.

Has this changed the meaning of photo captions?

Yes, it changed everything. I think that captions can be more voluminous, more relevant. For example, you write that on January 14, [the day of the shelling of a residential building in Dnipro], you saw two girls playing in the park, and 30 minutes later, the shelling happened. And you could do more things like that. Besides, it’s a good idea for a photographer to say what he feels. Just like a writer, he can say how staggeringly it was.

In your article for Revue, you wrote that AI images can be used as a weapon to encourage racism and misogyny, as well as to provoke violent conflicts that undermine the democratic process. Could you elaborate on this?

You can take a picture of someone stealing something, even though they never did it, and if you have images of white people stealing things, or foreigners, or Hungarians, or anyone, you can use them as a weapon to show something that never happened. Let’s say there’s a picture of a Russian soldier, and there are a lot of dead people in the background, and you can easily make him smile with artificial intelligence or Photoshop. It’s a weapon, it’s propaganda, and at this point, everything falls apart. Especially on social media, because there are no filters anymore. When I worked at the NYTimes, we had a filter to make sure the photo was authentic, because it’s your reputation. But on social media, people can post anything.

Why would people do that? Do you have an explanation?

There are many reasons: for example, I hate Russians, I hate Ukrainians, Americans, anyone. When [Democrat] John Kerry was running for president, some guy used Photoshop to put him in a photo next to Jane Fonda, an actress who many people hate because she went to North Vietnam and is considered anti-American. But he had never met her. These things are very easy to weaponize.

Social media users have been sharing a photo claiming to show actress Jane Fonda with politician John Kerry at an anti-war rally. This photograph was digitally altered over 19 years ago.

But you can say that you’ve never seen this woman [or that it’s photoshopped].

It was 20 years ago. I’ve met a lot of people — maybe she was standing next to me, and I ask myself if it really happened. And it’s really scary because you don’t know what happened and what didn’t. Millions of artificial intelligence images appear on the Internet every day, and so the best thing a photographer or videographer can do is to put each of their works in context so that they can be trusted.

The main headline in today’s NYTimes is about how universities are changing the way they teach by using artificial intelligence to work with texts, because their students are writing essays with AI, and the same can happen with images. They also don’t know how to work with text. Everything is moving very, very fast.

Image created by artificial intelligence for the query “The most iconic photo of the war in Ukraine”. Kateryna Serhatskova / Zaborona

Do you think that images are more powerful than texts in this sense?

For me, the problem is that photographs can be iconic, they can create a big international discussion, and photographs from Vietnam, I think, had a big impact on the US to stop the war. Photos from the war in Afghanistan, which lasted 20 years, are not iconic. So you cannot use them to oppose the war.

I think that during the war in Ukraine, we see more and more images that people do not respond to. Therefore, the question of what other images could be made to make people react is important. These can be not only images of violence, but also other aspects of what is happening in Ukraine or with refugees. And this is an important question — how to get people and governments to react, because if it’s just destruction, it repeats itself, and people don’t react. I don’t think since 2015, when a three-year-old boy [Alan Kurdi], who was killed with his relatives while trying to leave Syria, or after the video of George Floyd, who was killed by police, there has been any iconic photo on the international level. And this is a problem. But in the case of Ukraine, I would like to ask: what kind of images will help people understand the horror of war and respond to it? It can be something other than destruction. When I was working on a photo book with young people in Ukraine, I showed them not crimes or destruction, but the idea that photographs can be quite simple — even very banal images, such as a farmer and a cow.

When we were working on the genocide in Rwanda, the NYT wanted to show the hope of children, not the victims. And it had a greater impact. And that video about George Floyd was made by an amateur, not a professional, and many of the great photos were taken by soldiers, not professionals. People are curious about what it’s like to survive, to try to have fun, to sleep at night during a war, or what you see first thing in the morning, or how you can’t sleep because of the war. Sometimes professionals see big things, but they don’t see the very important little things.

Turkish gendarmerie stand near by the washed up body of a refugee child identified as Alan Kurdi who drowned during a failed attempt to sail to the Greek island of Kos, on the shore in the coastal town of Bodrum, Mugla city, Turkey, September 02, 2015. EPA / DOGAN NEWS AGENCY

So do you think there are no iconic images from the war in Ukraine? Were there any photos that touched you?

Of course, there were strong photos. For example, the photo by Lynsey Addario, in which the whole family was killed in the street [the photo was taken in Irpin in March 2022]. But I’m trying to figure out what kind of images can make people sympathize: for example, a grandparent in an apartment without heat. Everyone understands what it’s like to be old without food — in any country. So there are many ways to do this, to build bridges and connections.

When I was writing about the Vietnam War, I saw photos of the ID cards of 240 young American soldiers who had died. Life magazine thought that this was what was intended to turn people against the war, not the pictures of the destruction. And people said: “Oh, that could be my cousin, brother, or neighbor.” I think we need to use many more strategies.

Heartbreaking photo by @lynseyaddario @nytimes all the world should see. ‘Ukrainian soldiers trying to save the father of a family of four — the only one at that moment who still had a pulse — moments after being hit by a mortar while trying to flee Irpin’ https://t.co/OTpDQjxcqb pic.twitter.com/uhbzg0ZyW5

— cindygallop.eth (@cindygallop) March 6, 2022

Do you remember the photographs from Mariupol taken by Yevhen Maloletka? The invasion had just begun, Russia was shelling the city very intensively, and Maloletka took some photos of women in a maternity hospital. They were everywhere, and people [in Ukraine] believed that these photos could change something. But I think in the end they didn’t change anything.

You’re probably right, but in most countries, there are no more front pages of the news, no more printed newspapers — so we don’t have photographs that stand like icons anymore. Everything is small on the screen, and there is nothing to talk about. On the front page of a newspaper, you talk to people, you create a community. So you can’t use the ideas of images from the 20th century in the 21st, because we don’t have those presentation mechanisms anymore. In addition, we see too many images, and there was only one on the front page. You can’t focus on the Internet. It’s a completely new world. There are so many things that don’t mean anything anymore.

Ukrainian emergency workers and volunteers carry an injured pregnant woman from a maternity hospital damaged by shelling in Mariupol, Ukraine, Wednesday, March 9, 2022. The baby was born dead. Half an hour later, the mother died too. Photo: Evgeniy Maloletka / AP

Do you think that changes can happen in this brand-new world?

It’s not just one change, but many changes: billboards, posters, and multimedia projects. To make children [at war] talk about what you had for dinner, what your favorite sport is, or what your father is doing at war, or that you no longer have a father.

And who should do this? Editors, journalists?

Everyone should be involved in different ways.

I think that many people create a picture of something that never existed in order to attract attention.

Okay, I do, for example, a picture of the first female president in France, which never existed, or another black president in the United States. You can do it in certain ways, but again, AI might be interesting in the future to provoke debate. In English, this is called the liars’ dividend: when so many fake photos appear we stop believing in the true ones. And another problem is that professionals take the same photos over and over again.

Variations of images made by artificial intelligence for the query “The most iconic photo of the war in Ukraine”. Kateryna Serhatskova / Zaborona

Can artificial intelligence change a photo?

Yes, it can. If I ask a Ukrainian child: “What is your dream or nightmare?” and put it into artificial intelligence, show the image to the child, and publish it, it can be really interesting. “This is what a 12-year-old child in Ukraine dreams about.” Or ask the same elderly people. Some are 85 years old. What are you afraid of in Ukraine? They describe it to you, and you show them a photo taken by AI. Does it look like your dream or fear? But this is not what we talked about at the beginning.

Theoretically, could artificial intelligence change photography in a way that would increase the credibility of documentary photography or journalism?

One thing I’ve already learned is that when using artificial intelligence, I’m always surprised. I’m rarely surprised by photos taken by real photographers — it’s always something expected, I know what I’m going to see — but photos taken by artificial intelligence surprise me. I ask what the best mother in the world is, and it shows me a gorilla, not a human, and it’s amazing because I never thought animals could be better mothers than humans. I remember a man who worked with me in Iraq during the war, and he took pictures of what people were eating, their dishes — I had never seen anything like that before. These are everyday things that humanize [the war]. Because the most important thing for me at the end of the day is that people are still people. And soldiers are not cruel people — they are human beings. They’re stuck in this horrible war, they have parents and friends, and you start to feel for them.

I gave a lecture about a girl who goes to the dentist in Iraq during the war, and this was the most important picture because they are people like us — they go to the dentist. They are not killing people all the time. They want a good life, they want to be happy. Like Ukrainians, they should be cruel because of the war, but they are not: they are just people.