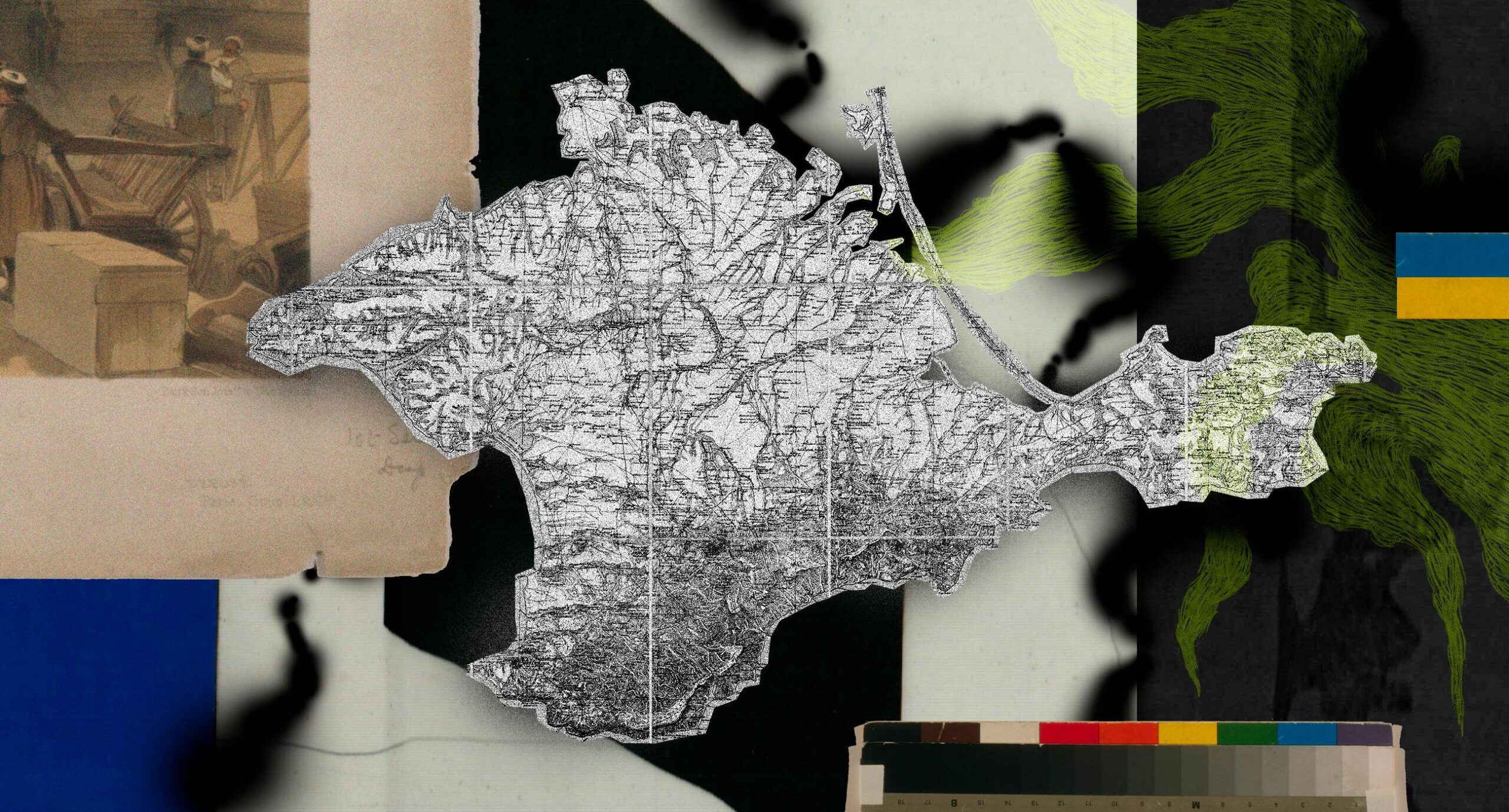

Zaborona continues a series of materials devoted to the occupation of Crimea and (de)colonial policy regarding the peninsula. In the first text of the special project, we talked about the most common Russian myths about Crimea: from the civilization Russia supposedly brought to the region several centuries ago to the bloodless ‘joining’ of the peninsula in 2014. In this text, we explain whether it is theoretically correct to say that Crimea, which was occupied nine years ago, is a colony of Russia. We found four justifications for this.

1773 — Russian army enters Crimea. After a policy of repression aimed at the indigenous nations, Russia forces the Tatars to sign a treaty. The result of the treaty was the establishment of an independent Crimean Khanate. One of the agreements was the obligation to withdraw troops from the peninsula (which, of course, did not happen). Ten years later, the Russian Empire occupied Crimea.

1777 — Russia makes its first attempts to interfere in the internal politics of the Crimean Khanate, advancing the careers of its candidates. As a result, Shagin Giray becomes an empire’s protégé (two years earlier, the Tatars had ousted another pro-Russian politician, Sahib Giray), thus violating the agreements of the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca regarding non-interference in the affairs of the Khanate.

1782 — Russia suppresses the rebellion of Crimean Tatars who were opposed to Shagin Giray, a pro-Russian figure. Dissatisfaction with his policies was so significant that even his personal guard joined the side of the rebels.

1783 — The first annexation of Crimea to the Russian Empire. This date serves as a cornerstone for pro-government historians, propagandists, and a significant part of Russian society. Having conquered Crimea 240 years ago, the reincarnations of the Russian Empire in the form of the USSR and the Russian Federation continue to assert that they have a special right to it simply because the peninsula was once part of the empire.

1783–1800 — The first waves of migration of Crimean Tatars as a result of annexation, destabilization of the Crimean Khanate, and religious persecution.

1860–1862 — A new wave of migration of Crimean Tatars and Nogais due to systematic oppression.

1901–1903 — The last wave of migration.

1918 — At the beginning of the year, the Bolsheviks seized almost the entire Crimea.

1944 — Deportation of Crimean Tatars by the USSR.

2014 — Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation.

Is the annexation of Crimea colonialism?

The annexation of Crimea in 2014 raised a complex question: can Russia’s unlawful actions be categorized as colonialism? Or is it some new, hybrid form of expansionism?

Before the occupation of Crimea and parts of Donbas, Russia, at least concerning Ukraine, could be described as a neocolonial state: its foreign policy towards neighbors aligned with almost all the characteristics typical of neocolonialist countries.

Here are a few of them:

However, the occupation of Ukrainian territories became a retrogressive act, taking Russia from the category of neocolonialists back to the ranks of old-regime colonizers from the 19th century. In essence, Russia remains the only former empire that continues to pursue a colonial project, unlike all colonizing countries that abandoned territorial claims in the 1950s and 1960s.

According to critics of the Kremlin’s policies, the annexation of Crimea, along with military actions in mainland Ukraine, Chechnya, Moldova, and Georgia, represent contemporary anti-colonial wars, or more precisely, archaic wars aimed at maintaining influence over former colonies. Historian Philip Longworth believes that Russian President Vladimir Putin is attempting to create the fifth reincarnation of the Russian Empire.

However, Russian colonialism has different characteristics from European colonialism. According to some academics, European colonialism had positive outcomes for the colonized country. American-Canadian historian Bruce Gilley and Scottish theologian and ethicist Nigel Biggar argue that, despite racism, violence, and in some cases genocides, British and French colonialism was a positive phenomenon. According to them, after the so-called “evangelical enlightenment,” colonialism transformed into a liberal project aimed at ending regional conflicts between tribes and ethnic groups, suppressing the slave trade, as well as organizing democracy, the legal system, technology, medicine, and education.

However, contemporary Russia is experiencing a crisis of political ideas, economic and technological stagnation — it would be a significant exaggeration to say that Putin’s colonialism is aimed at innovation; it is an archaic, resource-driven, and territorially expansionist campaign.

Here are a few factors explaining why this is the case.

Russification of the region

Ілюстрація: Марія Петрова / Заборона

Despite statements from the political establishment that the Russian Federation is a multi-ethnic country (which is true), the occupying administrations in Crimea are implementing a nationalist policy, Russifying the annexed region, assimilating or persecuting the ethnic groups present on the peninsula. At the time of the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Empire in 1783, 90% of the population consisted of Crimean Tatars. There is no point in describing the stages of displacement of Crimean Tatars and other indigenous peoples — it is sufficient to add that with the support of the Russian Empire and the USSR, by 2014, ethnic Russians constituted the dominant part of the peninsula’s population, which significantly fueled the propaganda of the Russian Federation today.

But the displacement of indigenous peoples did not begin in 2014. Colonialism always creates subalterns — oppressed social groups deprived of political voice and agency. However, policies of oppression can have several levels. For example, Ukrainians in the occupied territories are positioned as subjugated “Little Russians,” while Crimean Tatars are not only subjugated but also considered as the “other.” The dual level of suppression policies directed at them also entails a policy of exclusion as unfamiliar and culturally distant foreigners.

According to historian Jeffrey Hosking, one of the most illustrative examples of erasing a different identity is the implementation, even during the time of Peter the Great, of the distinction between “russkiy” (ethnic Russian) and “rossiyanin” (imperial Russian) — the ethnic majority and the subjugated and integrated into the empire ethnicity (similar distinctions can be found in other former imperialist countries, such as between English and British or between Turk and Ottoman).

Toponymic aggression

Illustration: Maria Petrova / Zaborona

Crimea was a periphery of the Russian colony during the times of the Russian Empire, the USSR, and the Putin Federation — hence, the Russification of the region and the erosion of Crimean Tatar identity began several centuries ago. According to geographer Boris Radoman, modern Russia continues what he called a policy of toponymic aggression — renaming natural and urban landscapes into Russianized versions.

Vakuf-Kardzhav, Djaga-Chelebi, Sarayli-Kiyat, Aydar-Gazi — these are authentic names that are not only Russified at the administrative and everyday language level but also in literature and on maps, leaving the circulation of these toponyms only within limited social groups.

During the decommunization process in May 2016, the Ukrainian government adopted a resolution through which 70 populated areas had their original Crimean Tatar names restored. This was not only an anti-communist action but also Ukraine’s initial steps in a decolonial movement.

Necropolitics regarding migrants

Illustration: Maria Petrova / Zaborona

Describing the concept of necropolitics, Cameroonian philosopher Achille Mbembe wrote, “to practice sovereignty is to exercise control over mortality.” According to Mbembe, whose works have become an important part of postcolonial studies, colonial states exploit the resources of the occupied country, destabilizing its economy and social mechanisms. Unable to lead a dignified life in the occupied country, its inhabitants seek work in the metropolis, becoming immigrants.

According to Mbembe, necropolitics is not only the politics of deliberate destruction of certain social groups but also the politics of choosing who will die (to let die). When becoming an immigrant, a person finds themselves in a gray zone without access to healthcare, security, and legal protection, becoming what is known as the precariat — an individual whose life is threatened by the conditions of their existence.

In the article by sociologists John Round and Irina Kuznetsova, it is mentioned that Putin’s Russia (especially evident in the policies of Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin) systematically implements necropolitics targeted at migrants from Central Asia and the Caucasus (the article doesn’t specifically refer to Crimeans, but it’s possible that migrants from the peninsula are not an exception). Non-Slavic migrants typically work in poor conditions, forming a group that Mbembe refers to as the “living dead” mobilized for labor and work.

Memoricide

Illustration: Maria Petrova / Zaborona

The Russification of the region and toponymic aggression also serve the goals of memorial politics, a strategic project designed for decades (or centuries), aimed at erasing the memory of a certain history, social group, or language.

Russia, like other neoconservative political forces, can be described as a regressive country that constantly appeals to its (mythologized) history while feeling a deficit in futuristic narratives. In simpler terms, the Putin government cannot offer a worthy model of the future, so it turns to a familiar past.

The past and history are pliable resources, like clay, that can be molded according to political circumstances. In essence, by russifying history and giving Russia a prominent place on the world’s political map, Kremlin strategists deliberately erase collective memory of perpendicular and opposing narratives: for example, the historical connection of Crimean Tatars and other Turkic peoples. The colonizer’s task is to integrate the occupied country into the body of the state, including washing away any mention of its alternative, pre-colonial history from the collective memory.