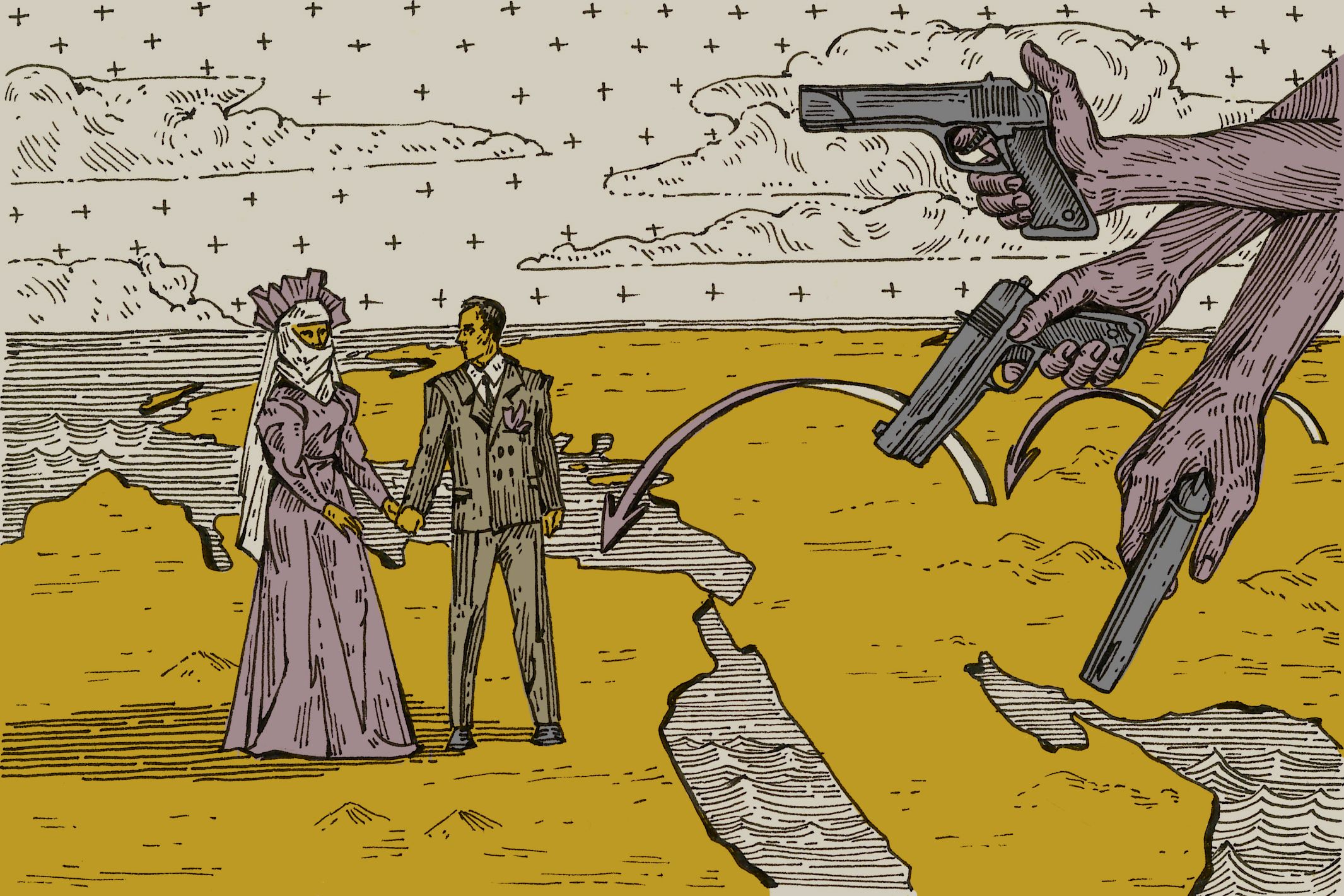

Anna and Yusuf.

How Similar Methods of Fabricating Religious Terrorism Work in Ukraine and Poland – and Why it’s Dangerous.

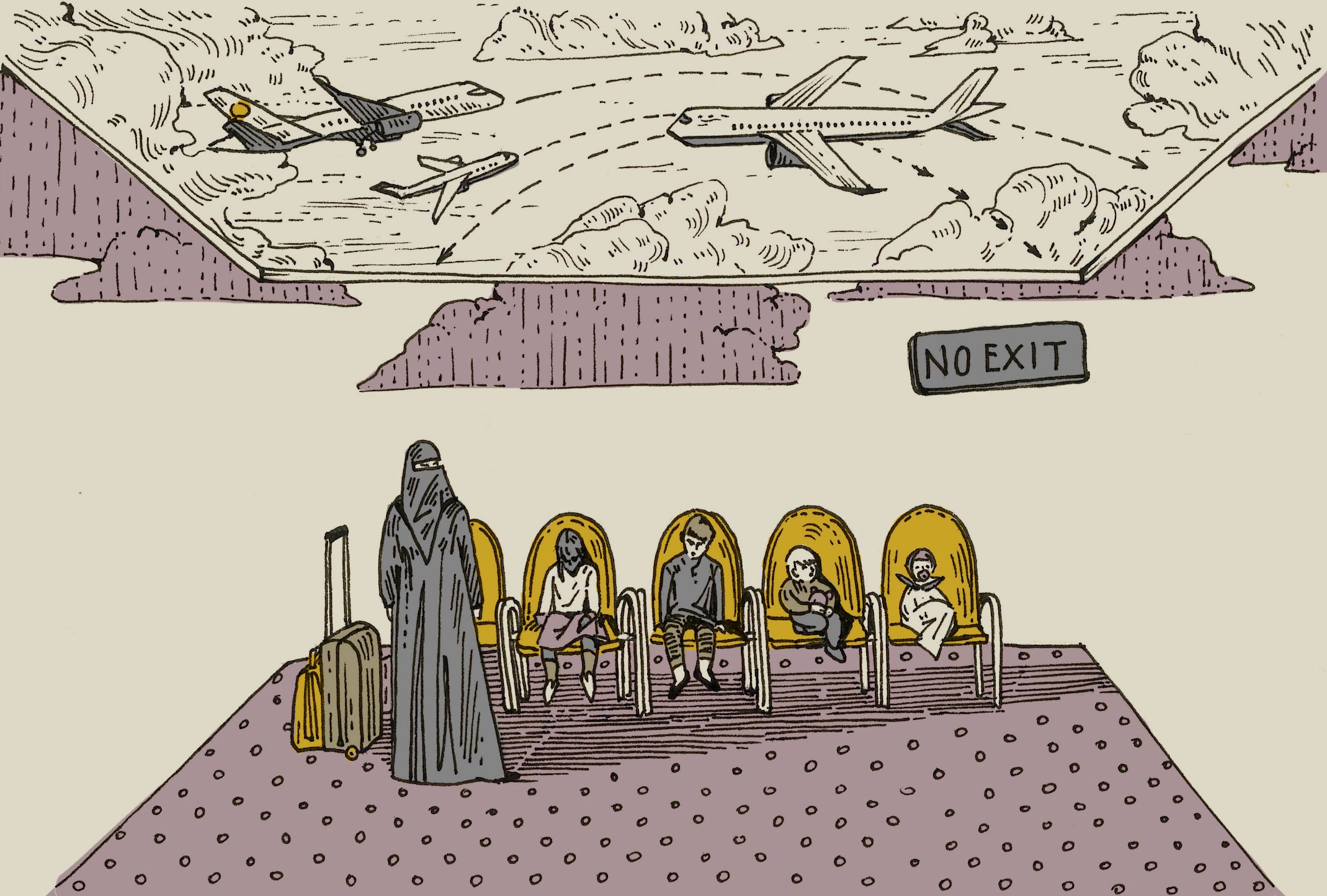

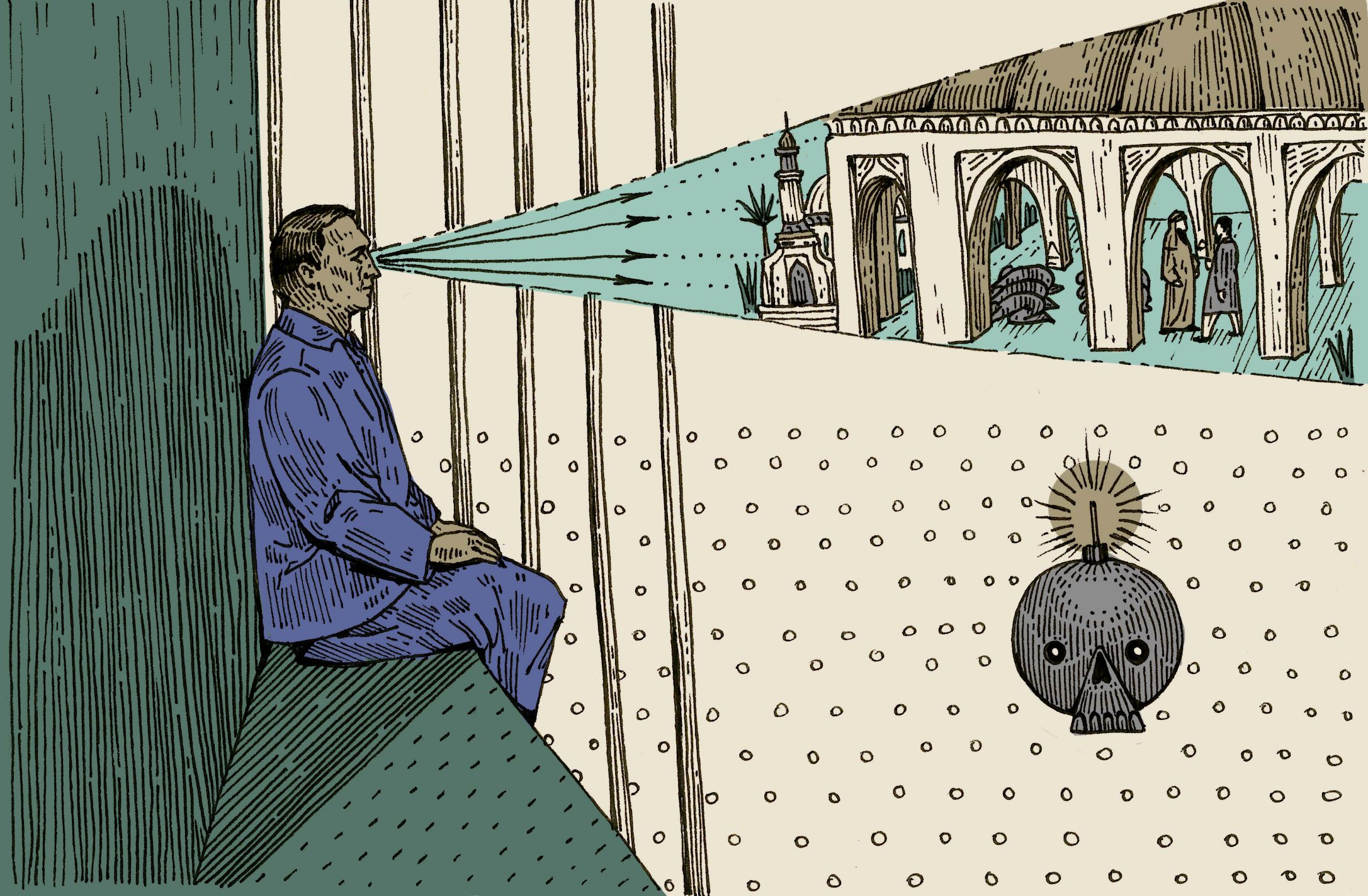

Illustrations: AVE

Accusing Muslim foreigners of religious fanaticism is a state tactic used for internal purposes, like creating the feeling terrorism is under control. Authoritarian regimes use it to send unwanted citizens back to the country of their origin. This tactic is facilitated by the lack of knowledge and interest of special services in countries such as Poland and Ukraine. Polish reporter Pawel Pieniazek and Ukrainian journalist Alyona Savchuk investigated how states unjustifiably accuse foreign Muslims of terrorism and tell parallel stories of the arrest of a Tajik man in Poland and a Russian woman in Ukraine.

Anna Karakotova is a young, slender woman in a black hijab and dress, with a one-year-old baby in her arms. We met her in the yard of a residential complex in Pechersk, an elite area of Kyiv, next to the building of the State Migration Service of Ukraine. Her husband, Mahomed Abdulkarimov, had just gone to the migration service to ask officials to accept his wife’s documents. If Karakotova’s case is denied, she and her five children will be deported to Russia. Only a request for political asylum could stop this process. She herself did not dare to go to the officials, as she was well aware there have been cases before when unknown criminals abducted such people like her on the street near the migration service and took them abroad for transfer to Russian law enforcement agencies.

Karakotova’s status in Ukraine is uncertain. She has been waiting for refugee status for more than three years, trying to prove that Russia has fabricated a criminal case against her for participating in the Islamic State, which many countries consider a terrorist organization. Back in Russia, she faces arrest, trial, and detention in a penal colony. One by one, Ukrainian institutions are consistently sending her away, trying to get rid of the problem. They believe she might have connections with terrorists, but the only source of such information is the Russian Secret Service, which can’t treat her case fairly.

Yusuf is a young man from Tajikistan with dark hair and dark eyes. He was living a quiet life in Poland until one day, when he left home to go to Mokotow, a residential area of Warsaw, for a meeting at the Polish Internal Security Agency. The secret services wanted to meet with him because, as they said, it was a concern of national security. Yusuf had been in contact with them before, so it looked like another regular meeting. However, this time it was not just a conversation. He was handcuffed and put in a car.

He later found himself in court. From a computer screen, the judge said that he had been charged. Yusuf asked what he was being accused of, but he was told that it was a state secret. The court did not provide any evidence and ruled that Yusuf should be deported to Tajikistan, of which he is a citizen, and that he was now barred from entering the Schengen area for five years. Until deportation, he must be held in a detention center in Przemyśl, a town in south-eastern Poland, where he was immediately sent. At first, he was to spend three months there, but then his arrest was extended for another three. Today, Yusuf is still in custody.

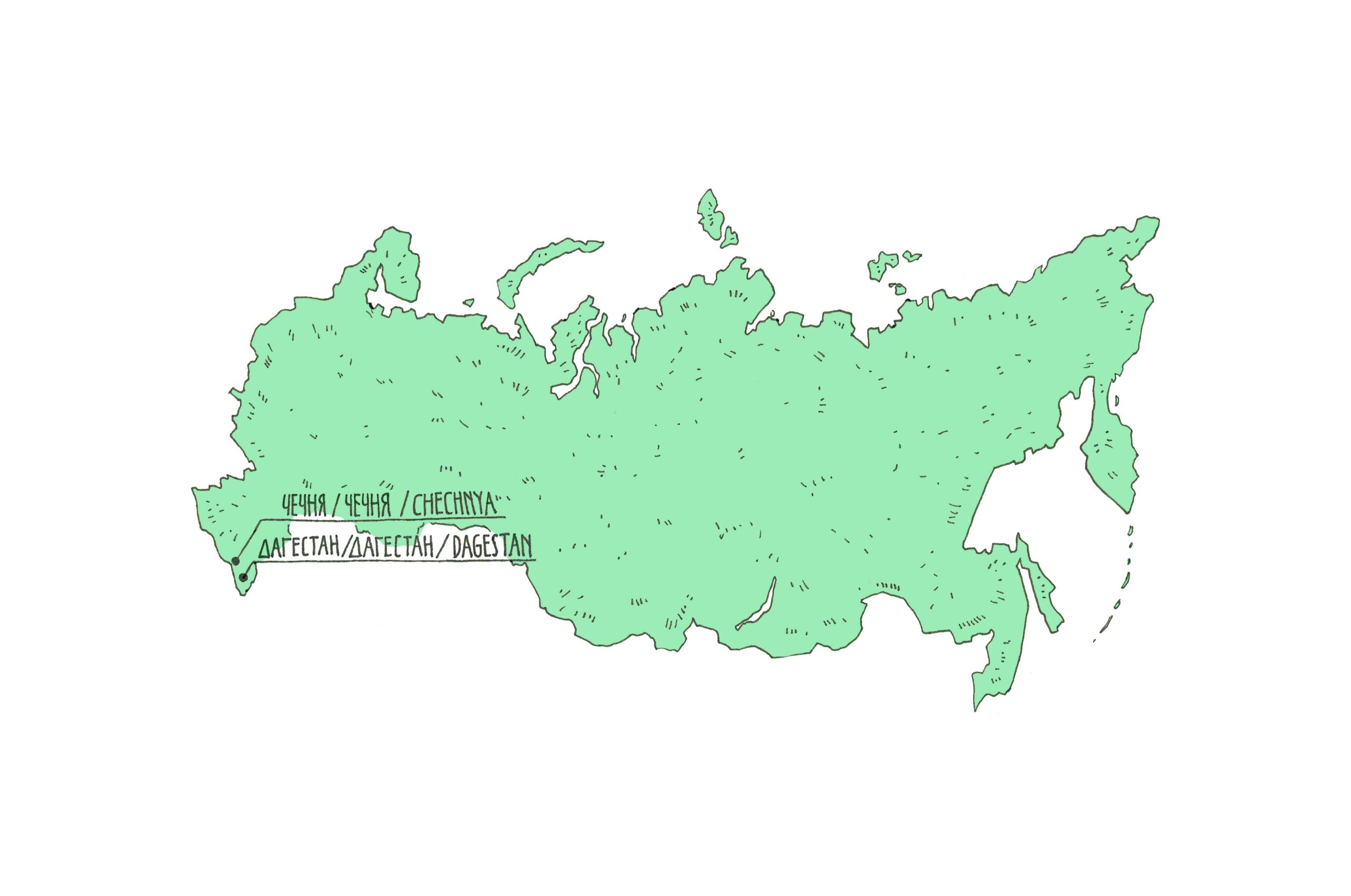

The story of Anna Karakotova started a long time ago in Russia when she was in her early twenties. She was born in the Russian republic of Karachay-Cherkessia, grew up in a Christian family, and converted to Islam at 20. She met and married Kalimulla Sapigulaev, a Muslim from Dagestan. They settled in his homeland, but then one day he disappeared. Earlier he had told her that he was being watched, and they were considering whether they should leave Dagestan for a while. One day he went to work and never returned. After the disappearance of her husband, Anna gave birth to their second child.

Sapigulaev’s family spent that year trying to learn something about his whereabouts. They followed every possible lead. But on the night of February 16-17, 2013, special services killed three alleged militants in a forest in Dagestan. One of them, according to the FSB, was the missing Sapigulaev.

“They accused him of terrorism, claimed that he was a member of an armed group. We were all shocked,” Karakotova recalls. The FSB didn’t present any evidence.

She is convinced that Sapigulayev was dealt with because of his criticism of the authorities.

“It’s not the first time something like this has happened. They (special services) continue to kidnap young people from villages and then they ‘disappear’. Wives and mothers go with posters in search of their husbands. Many of them are not found, because they are tortured and hidden away somewhere,” says Karakotova.

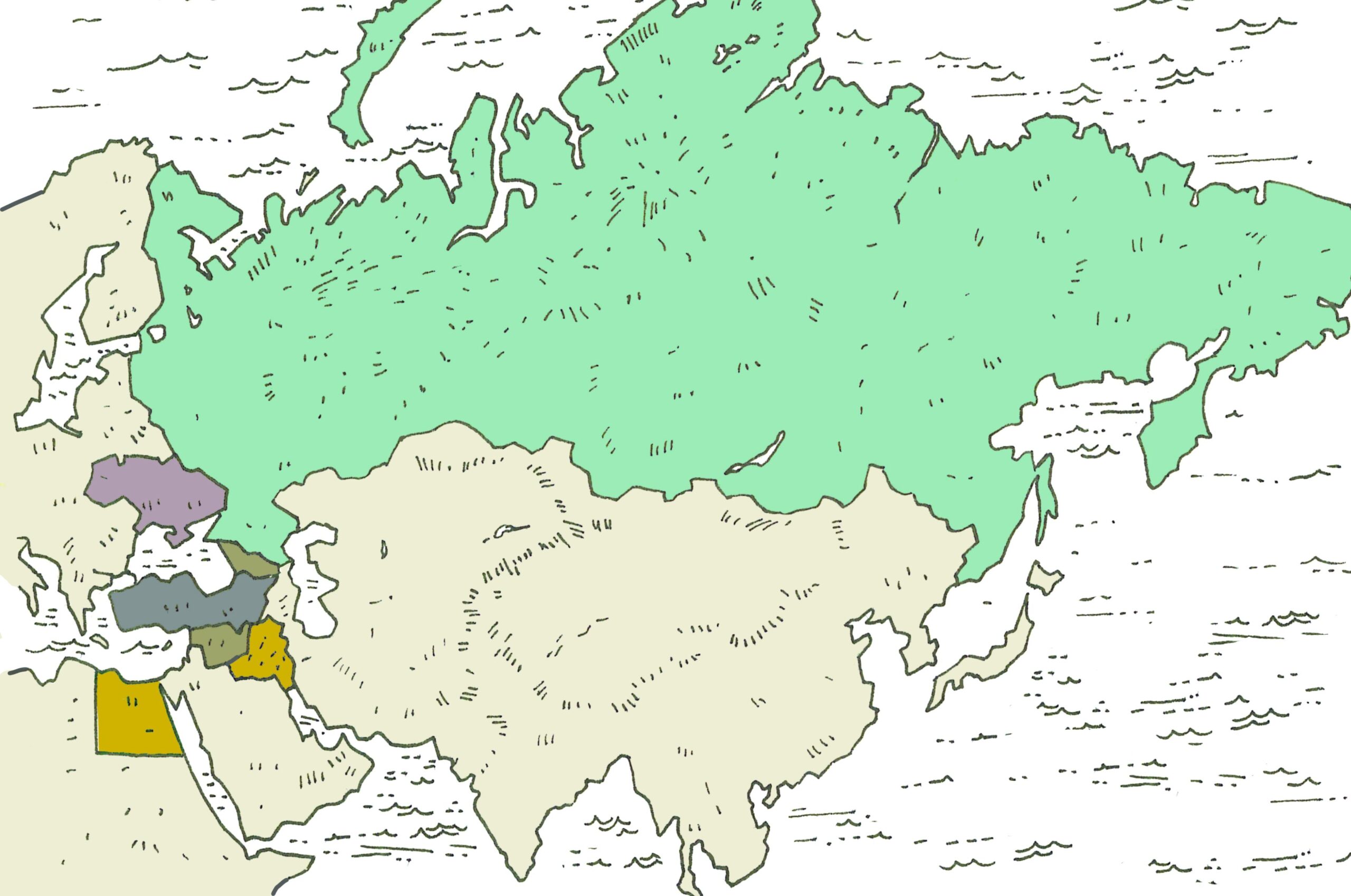

The abduction of Muslims in Dagestan, Ingushetia, and Chechnya is an echo of the wars in the North Caucasus. Since the second Chechen war ended with the destruction of most militants and pro-independence republics, the region has been regularly raided by so-called anti-terrorist operations. Local authorities position these special operations as a fight against religious terrorism, but, as Anna claims, it is usually a crackdown on active young people who disagree with the positions of local officials and intelligence services.

From the moment when the special services announced Sapigulayev’s execution, Karakotova’s life became hell. FSB officers came to her home and called her the “terrorist’s wife.” Later, they made it clear that it would be better if she left Dagestan. She decided to return to her parents in Karachay-Cherkessia. But even there, she had no peace. Almost immediately after her arrival, FSB officers took her in for questioning. In the end, they told her that she had to go. Otherwise, they would not let her live, and sooner or later, they would find “something” to do with her.

Karakatova left for Turkey with her two children, and a month later went to Egypt. She believed that this was a good place because the children would be able to learn Arabic, receive a proper religious upbringing, and life there would not be too expensive. She moved to Alexandria and remarried, this time with Yaksub Omarov, a student from Dagestan.

At first, everything was fine: her husband was studying; the children went to kindergarten. However, from time to time, ominous information came from her house – her bank accounts were blocked; special services went to her parents and asked them about her. They persuaded Karakatova’s mother that her daughter had lived in Syria for a long time, although at the time Karaktova was visiting the Russian consulate in Alexandria to register her newborn.

After some time, Omarov was deported from Egypt.

“As soon as his residence card expired, some people caught him on the street, put him in a car, and took him to the deportation center. He chose Turkey as a transit country and managed to escape there,” Karakatova said.

For a year and a half, she lived alone in Egypt with four children. Finally, her husband told her that he could support them and asked them to come to Turkey. They immediately packed up and flew away. Karakatova was not yet aware that this decision would radically change the life of her family.

Polish Internal Security agents knocked on the door of Yusuf’s house when he was already in the detention center and did not introduce themselves at first. His Tajiki wife, who takes care of the children at home, opened the door. They had been married for only a relatively short time. Yusuf had been living in Poland for several years, working part-time.

Yusuf’s wife did not know what had happened to him. Agents told her that her husband was at work, which she did not believe because he did not leave the house due to the quarantine. They searched for his passport, searched the entire apartment until they found it. After Yusuf’s arrest, his wife found herself in a difficult situation – without a job, without the ability to pay for an apartment and support herself and their children. She had to ask for help from her family.

In addition to Yusuf, three other Tajik nationals were arrested that day. All of them are under arrest in Przemyśl, awaiting deportation.

Anna Karakatova’s trip to join her husband did not go well. At the Turkish airport, border guards told Karakatova that they would not allow her and her children to enter the country. The translator explained to her that there was a “code” for her, so she could not enter the country, but at that time, she did not know what the “code” was. They took the next flight back to Cairo. To her surprise, she was not allowed to re-enter Egypt.

Where to go next? She did not know and did not have enough money for tickets. She spent about two weeks with her children in the transit zone of the airport. During that time, she raised money for tickets to Georgia. There, according to her, it would be easier for her to find out what was happening and why she wasn’t allowed to see her husband. She was also refused entry to Georgia. She asked and begged but was told that she should immediately leave if she did not want problems.

The woman found herself in the Turkish transit zone again. She said she wanted to apply for asylum, but two border guards persuaded her to board a plane with them and fly to Cairo together so that they could help her stay in the country and get a visa at the Turkish consulate. But the border guards had deceived her. Karakatova and her children found themselves in front of a closed door at Cairo airport again.

This time they spent 20 days at the Cairo airport. Relatives raised money. Karakatova wanted to go anywhere except Russia. One of her acquaintances advised Ukraine, a country in conflict with Russia. It also had relatively good health care. At that time, her children needed medical care.

On April 17, 2017, the family arrived at Kyiv’s Boryspil Airport. During passport control, Karakatova collapsed from fatigue. To her surprise, she was handcuffed. She was told that Interpol had issued her a “red notice”. This is an accusation of a particularly serious crime, for which she was threatened with arrest and extradition to Russia. Despite her pleas, the police took the children away, and she did not see them for three days.

During subsequent meetings with authorities, Yusuf learned there was a threat he might commit terrorist or espionage activities. However, since then, he has not received any further details. Documents to confirm these allegations are classified. Neither Yusuf nor his lawyer has access to them. This is the result of a Polish anti-terrorism law introduced in 2016, which has been heavily criticized by experts. In a situation where a lawyer does not have access to a case, it is extremely difficult to protect a client because it is not even known what they are being accused of. Eva Ostaszewska-Zhuk, a lawyer with the Helsinki Human Rights Union Committee representing one of the detained Tajiks, admits that for this reason, it is not even known whether the Internal Security Agency has taken reasonable steps.

“It may be that there is nothing in these documents, but it can also be just a form of agency pressure on foreigners to cooperate with them,” said the lawyer.

The court was not interested in Yusuf’s explanations that he could face torture and up to thirty years in prison in his country for such charges. This is beyond the fact that Tajikistan is an authoritarian country where human rights are systematically violated. The court also did not take into account family circumstances – Yusuf’s wife, who remains in Poland, has severe health problems and cannot provide adequate financial conditions for their children on her own.

Yusuf was interrogated about Maksym S., admitting that he once saw him in a mosque but had no contact with him. He reported this to the Polish Internal Security agents during preliminary talks before his arrest.

Maksym S. was arrested on December 4, 2019, by the Internal Security Agency. According to TVP Info, sometime between late September and early October 2019, his colleagues noticed that something was happening to him – he had changed rather quickly. The reason was allegedly a breakup with a girl, which he was handling poorly. Then, Maksym seemed to convert to Islam in one of Warsaw’s mosques. There he was to meet with fundamentalists from Tajikistan and Chechnya. It was during one of the ceremonies that Yusuf probably saw him.

Once, writes TVP Info, Maksym began to tell his friends that he wanted to punish the infidels. He began to learn how to design an explosive. Almost immediately after his conversion to Islam, he planned, according to intelligence services, to drive into a shopping center in Pulawy in a Toyota Yaris and blow up the goods previously placed there.

Maksym is a 27-year-old Ukrainian from the Ivano-Frankivsk region. Before he departed for Poland, he served in the Ukrainian army. He lived for three years in Pulawy, Lublin Voivodeship, and often visited Warsaw. He cooked sushi in one of Pulawy’s restaurants. People who used to work with him said that he was very closed, looking for acceptance; he was fond of art, painted. They were rather bleak landscapes. He was alone, and his colleagues said that even though he was weird, he didn’t cause any problems.

Two days after Anna’s arrival, her case was heard in the Boryspil City District Court. The prosecutor requested Karakatova’s temporary arrest pending extradition because the FSB accused her of involvement in the Islamic State, a terrorist organization in Russia. During the next meeting, Karakotova learned that she was supposed to have joined the Islamic State in February 2015. Since then, according to Russian intelligence and Ukrainian law enforcement, she has been near the northern Syrian city of Raqqa, treating the organization’s wounded soldiers and preparing food for them.

Karakatova denied all allegations, explaining that when she lived in Egypt, the children were attending a kindergarten in Alexandria, and she was visiting the Russian consulate to register a child born abroad. She was lucky because she was defended in court by good lawyers who could prove that the documents presented were insufficient for her arrest and contained errors. Judges released Karakatova from custody in the courtroom, and she immediately appealed to the migration service to apply for asylum and thus stop the extradition process.

However, the story did not end there.

The version of Maksym’s sharp radicalization is questionable. Even if the Internal Security Agency did track down the future suicide bomber, the operation would have been a dubious success. Almost a year has passed since the arrest, and as of September, preliminary investigations are still being prepared. Maksym was in a pre-trial detention center. In addition, no other persons were charged during the investigation at that time. There are only persons with the status of victims.

“The services filmed it, made a show, but it was not made public, which was expected,” says Professor Daniel Botkowski from the University of Bialystok, which deals with national security and religious fundamentalism. “They rushed with this. Perhaps, as is always the case, someone gave a political order from above, and the case was ruined.” He said it was likely that Tajik detainees, including Yusuf, had fallen victim to the political order.

The migration service denied Karakotova asylum. She appealed the decision and fought the migration service for three years. Meanwhile, lawyers managed to remove Karakatova from the Interpol database because the organization had doubts about the accuracy of the data provided by Russia.

Karakatova decided to divorce her second husband because she could not reunite the family. He was stuck in Turkey, and she was in Ukraine. It was in Ukraine that she met and married her third husband, Mahomed Abdulkarimov, from Dagestan. The whole family lived together in a temporary refugee center in Yahotyn, not far from Kyiv. In October 2019, their daughter Asiya was born there. The couple wanted to register her as a Ukrainian citizen, but the migration service did not accept their documents. The reason was that the mother did not provide a passport, as the migration service had previously confiscated it—a vicious circle. Now Karakatova is fighting in the court system for her daughter to become a Ukrainian citizen, to which she has every right.

On June 23, 2020, the Supreme Court of Ukraine refused to consider the appeal of the decision in the Karakotova case. As a result, the extradition process, which had lasted three years, resumed. The Ukrainian prosecutor’s office has prepared documents for sending her to Russia. With the help of human rights activists, lawyers, and media coverage, Karakatova took one last chance – she managed to re-apply for asylum in the newly discovered circumstances.

On September 8, 2020, the migration service refused to accept her asylum application and did not recognize the woman and her children as refugees. According to officials, there is no reason to believe that Karakotova is being persecuted at home.

Two of the four detained Tajiks were deported. Yusuf and another prisoner appealed to the European Court of Human Rights. In late August, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that extradition should be suspended pending the investigation. This could take anywhere from several years to several decades. Lawyers are trying to release them from a prison in Przemyśl because, according to Ostaszewska-Zhuk, there is no reason to detain them. Are they really a threat? Despite six months behind bars, it is still unknown, and Yusuf does not know what exactly he is being accused of.

Ukrainian human rights activist Damir Minadirov and his colleagues have been involved in similar cases for four years. He felt for himself what it was like to run away from home to fear losing his life or his freedom. Minadirov hails from the Crimea, where shortly after Russia’s annexation in 2014, he was abducted and tortured by FSB officers, forcing him to give false testimony against Crimean Tatars in a fabricated case of alleged terrorism. Minadirov understood that he would either agree to this or be put in prison. So as soon as he was released, he packed his things and quickly left the peninsula. He now lives with his family in Kyiv and, together with his colleagues, tries to help other people who find themselves in similar situations to Karakotova.

“In four years, we have had more than 50 such cases,” Minadirov said, adding that each time the migration service creates problems for immigrants. “However, so far, none of our clients have been extradited from the country.”

According to him, most of the extradition requests concern allegations of extremism and terrorism. Some are charged under two or three articles at once. When asked what forces Ukrainian law enforcement to extradite people to Russia, despite being at war with the country, Damir answers: “sympathy.” He explains that after the collapse of the Soviet Union, contacts between the secret services remained; they have tried to cooperate, understanding that colleagues – investigators, prosecutors, who requested extradition – rise up the career ladder thanks to such cases, so they help them.

Major General of the Security Service of Ukraine Viktor Yagun, former deputy head of this department in 2014-2015, admitted in a conversation with us that even if there is a shadow of suspicion of human cooperation with the Islamic State, law enforcement agencies do not care who provides this evidence. The thinking is that it is better to get rid of such a person than to have problems later.

Daniel Botskowski, a professor at the University of Bialystok, argues that Poland focuses too much on external terrorists rather than internal ones. There is an opinion that foreigners from Arab countries may carry out an attack, so Middle Easterners are looked at with fear. However, such attacks do not occur in Poland or Ukraine. Incidents are more commonly provoked by “lone wolves.”

Daniel Botskowski mentions at least two cases in the town of Staleva Volya in 2017 and 2018. In the latter case, a 20-year-old man drove a tractor into a mall and smashed a shop window with an ax. He was sober, and his motives were unknown. Almost a year earlier, there was a much more tragic incident. A 27-year-old man also attacked passers-by with a bayonet in the mall. As a result, a woman died, and eight people were injured. The malefactor was found insane and sent to a psychiatric institution for treatment. Both men were Poles.

“The stance of politicians in Poland is that there is no internal threat,” says Botskowski. “And since it does not exist, such people are considered crazy. It is difficult to assume that, for example, suicide bombers are emotionally balanced people and do not have any disorders. I bet most of them dare to take this step because they have such disorders, so it does not rule out terrorist acts.”

The professor considers such a policy a mistake that can end in tragedy because while paying attention only to fundamentalist threats, you can miss the real threats. “Someone is going to hurt us by shouting ‘your mother’ rather than ‘Allahu Akbar,'” he said.

Pawel Pieniazek

Alyona Savchuk

This article was created with the support of Journalismfund.eu. This is the result of Zaborona’s cooperation with the Polish “Gazeta Wyborcza”.