Your Grandmother’s Past: How to Find Information in the KGB Archives

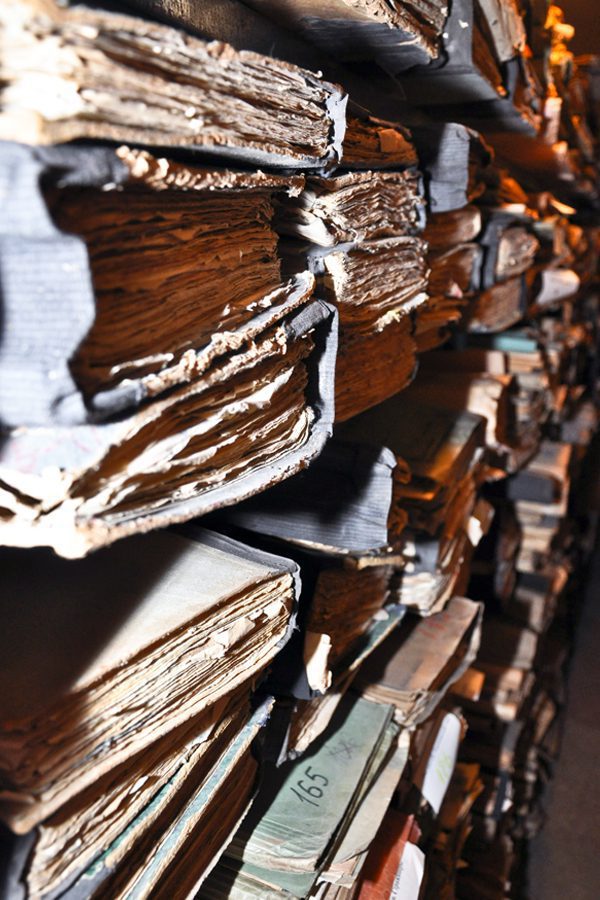

The archive volume of the Soviet Special Services in Ukraine is a conventional nine-story building densely filled with documents that have turned yellow from time to time. If you try to line up the KGB files stored in the Kyiv SBU archives, such a “bookcase” will be 7 kilometers long. After Euromaidan, the archives of the Soviet special services were released. Not only Ukrainians, but also foreigners can work with them. Zaborona journalist Samuil Proskuryakov tells how you can learn about your personal and family past, how you can see the world through the eyes of a special agencies worker and why the KGB archives have no place in the SBU.

The policy of access to the KGB archives in Ukraine is the most liberal among the countries of the former Soviet Union. Ukrainians and foreigners can easily examine documents and find out whether their relatives have been followed by agents of the Soviet special services. At the same time, the lion’s share of the KGB archives in Russia are still classified, and information about the oppressed can often not be obtained by ordinary citizens or historians.

According to the director of the Institute for National Memory, Anton Drobovych, the totalitarian regime with its political repression and persecution must be analyzed and examined so that it does not repeat itself. “The best prevention is to tell the truth about all the crimes of the totalitarian system that are vividly proven in the KGB cases,” said Drobovych.

Where are the KGB archives kept?

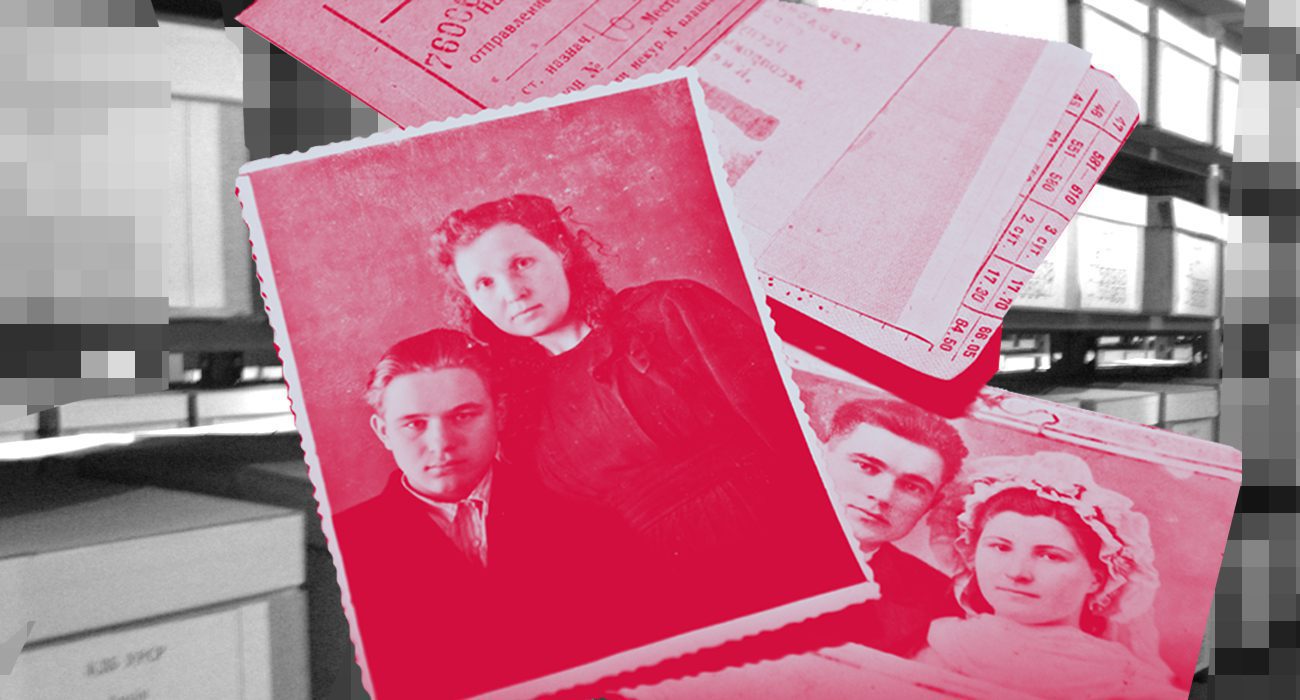

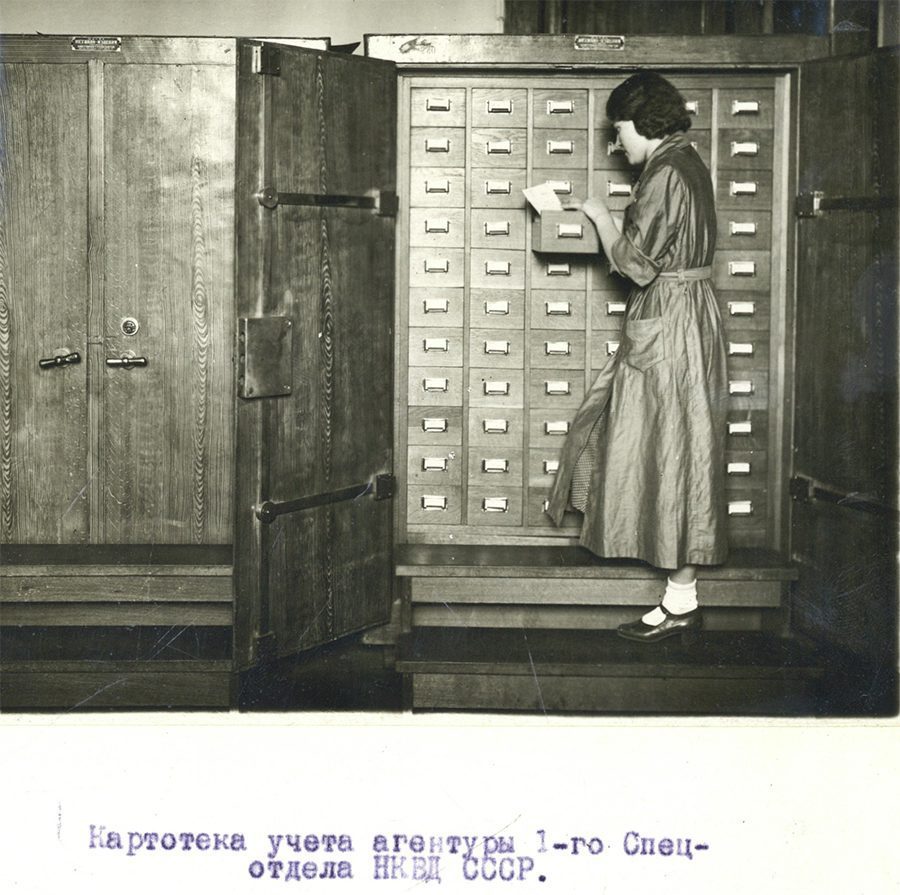

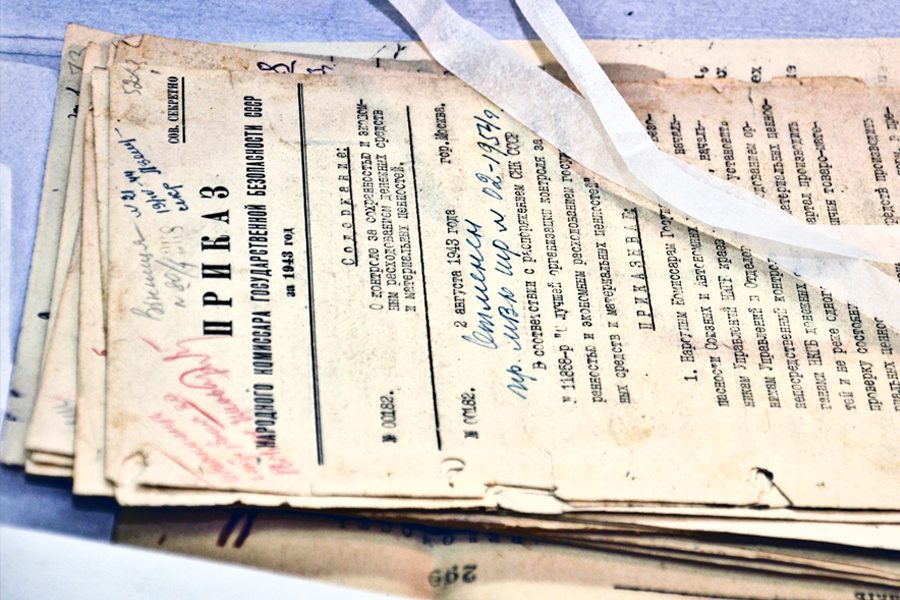

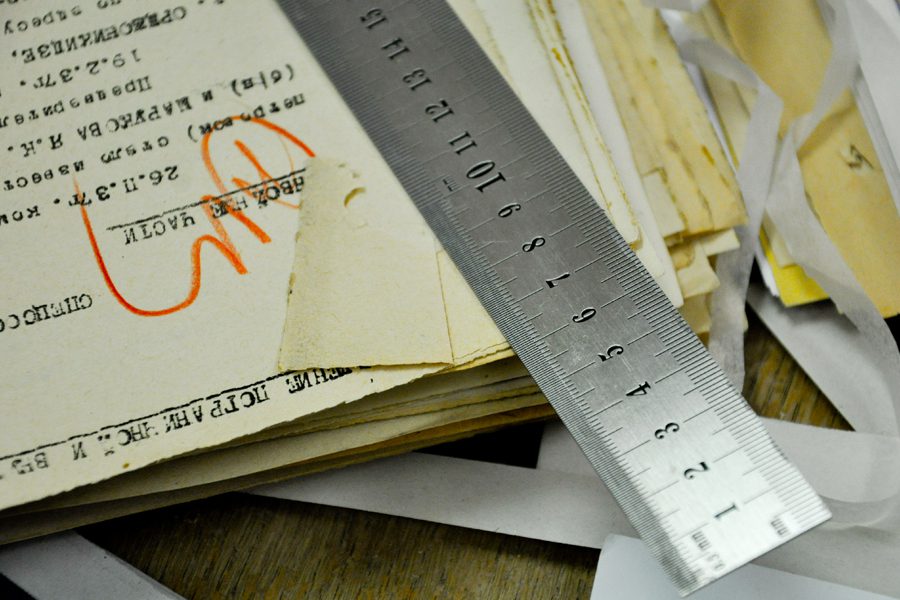

In the sectoral state archive of the Security Service of Ukraine. Archive director Andriy Kogut told Zaborona that there are almost 224,000 volumes in Kyiv alone. These are the regulatory and administrative documents of the Cheka-KGB, documents of secret and unclassified office work, annual work plans, reports and the like. And indeed political cases: arrest warrants and search warrants, questionnaires of the arrested, search logs, fingerprints, photos of the arrested, descriptions of the confiscated property, interrogation records of the defendants and witnesses, indictments, documents relating to stay in forced labor camps, letters, appeals, complaints of the defendant and his relatives, conclusions on the lack of rehabilitation reasons or a resolution on rehabilitation.

Photo: SBU archive

Photo: SBU archive Photo: SBU archive

Photo: SBU archive

Why are the KGB archives kept by the SBU?

On September 9, 1991, a decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet was issued, according to which the materials of the KGB should be transferred to the State Archives. They received almost one and a half million “filtration cases” against people who were forcibly brought to Germany and other countries of the Axis coalition during World War II. However, the transfer of the remaining funds to the KGB was prevented by the lack of space in state archives. Therefore, they remained in the Security Service of Ukraine, which received from Parliament material and technical support of the Soviet Special Service, including the premises where the KGB archives were kept.

According to Andriy Kogut, the KGB archives are toxic to the SBU. After all, “everything that is stored in the department, employees consider ‘their,’ part of their history.” The democratization of secret services and police cannot function properly if they protect documents containing information about massive human rights violations and continue to use methods from the archives of their predecessors. Transferring all Soviet affairs to an institution outside the security forces would break the chain of toxic continuity. This idea is already being implemented in the National Memory Archives.

Anton Drobovych agrees with Andriy Kogut. He says the SBU should only keep the SBU’s archives. ” [The National Memory Archives] will be a Mecca for Soviet intelligence researchers from all over the world,” says the head of the Institute of National memory.- The archive will collect the largest collection of released documents of the Soviet repressive organs and make them accessible to all. The archive of KGB files is larger than ours only in Russia. It is obvious that Moscow will not release it for the foreseeable future.”

However, the fate of this major project is questionable. This year, as a result of sequestration, more than 99% of the funds for the construction of the archive was directed for other needs. In the budget prepared by the government for the creation of an archive of national memory for 2021, there are no funds at all. This is in spite of the fact that these archives have already been granted a building, the property transfer has been completed, and the construction project has passed the state examination.

When were the KGB archives released?

The branch archive of the SBU was created back in 1994. The laws of the time had many shortcomings that both opened and closed the door to the secrets of the KGB. In general, access to the archive depended not only on the KGB, but also on other repressive Soviet bodies, including the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs. It also depended on the political situation and the wishes of the head of the Ukrgos archive, and the management of the security department in charge of the branch archive. The affairs of the KGB were and are kept by the SBU, documents of the NKVD — the Ministry of Interior, records of the secret services of Soviet Ukraine – the foreign secret service.

All documents from the Soviet era have been open and accessible since 2015. The activities of the Soviet special services and the NKVD were authorized by the law “On access to the archives of the repressive bodies of the totalitarian communist regime from 1917-1991”. Ukrainian citizens, whose relatives were oppressed at the time, had an opportunity to find information about them and historians to explore the tragic era.

Has much been saved from that time?

Sorry, we don’t know. The fact is that many documents were destroyed after the Stasi archives in East Berlin were seized in 1989. Moscow issued Order No. 00150, which, although did not contain direct instructions to destroy the documents, changed the period of time of storage. The archives have suffered most in the Baltic States.

Mostly they “cleaned up” documents that endangered intelligence officers. The further away from the present, the more documents have been preserved: the archives of the 1970s to 1980s suffered from the fact that the agents mainly destroyed information about themselves.

What was burned was recorded in special notebooks. But these notebooks were later destroyed. Therefore, today it is impossible to determine the exact extent of the losses.

Where can I find information on the Internet?

For a complete list of online archives and databases, see the KGB Media Archives manual. We indicate the main ones:

Electronic archive of the Ukrainian liberation movement;

Rehabilitated by history;

Ukrainian Institute for National Memory;

Archives of the Institute for Church History of the UCU;

Geroika;

National Museum of the Holodomor Genocide;

Ukrainian magazines archive online;

Saxon monuments to victims of political terror;

“Victims of Political Terror in the USSR” by the International Memorial Community (Russia).

How can you work with the KGB archives?

The basic information, which if lacking, prevents a personalized search consists of: surname, first name, patronymic, date and place of birth of the person you are interested in. Ask relatives, friends, acquaintances, neighbors, local historians and old-timers. Find out all possible variants of the first and last name: they could change, especially after the collapse of empires, changes in the borders of countries, regimes of occupation and administrative-territorial division. It is also important to find out the place where the person was living at the time of their arrest, detention, or repression.

For an event, check the local newspapers and magazines for the relevant time period. Some publications have already been digitized and are available online. If not, check out the local libraries. That’s exactly what we did when we were preparing the “Run or Die” material on Kriviy Rih’s teenage gangs and found newspapers and photos from the second half of the 1980s.

Sometimes old editions and publications of documents are kept in museum and monuments collections. They can also store documents, photos and personal items.

You can find a lot of information on the Internet.

And then what?

You need to write a request. It can be an email or normal mail. Examples of inquiries, contacts and emails here.Your inquiries will be registered as official letters and the archive will have a month to search for information and answers.

If you are interested in the SBU, you will be invited to the archive. When we talk about the regions, you will be directed to the regional office which will provide the name and contact number of the archivist responsible for your calling.

Next, arrange a time when you can work on the case. You will be given a pass, as the archive is on the SBU’s territory, and then you can familiarize yourself with the case. And even shoot or scan with flash without flash – for free.

If you are a foreigner or you are having difficulty coming, you can ask to digitize the documents and send them by email. If the amount of data required is too large, digitization is done at your expense.

If the documents are not in the SBU, the archive will indicate where else to turn. For example, documents relating to deportation, eviction, expropriation of kulaks and criminal matters related to the Holodomor are kept in the Archives of the Ministry of the Interior.

Andriy Kogut emphasizes that within the KGB archives certain documents are stored that do not always contain reliable information about what the suspects or the oppressed actually did and how they lived.

Translated by Cornelia Kruger from the Respond Crisis Translation