In one town in Ukraine, police demanded a list of Jews from the head of the Jewish community. We tell you about the history of antisemitism there.

In mid-February 2020, the Department of Strategic Investigations of the National Police of the Ivano-Frankivsk Region sent a letter to the head of the Kolomyya Jewish community requesting a list of Jews living in the city. On May 9, the letter was published by Eduard Dolynsky, director of the Ukrainian Jewish Committee, adding that such letters “resemble the year 1941,” when Nazis and collaborators compiled lists of Jews to be shot. Zaborona revealed that such requests were received not only by the Jewish community, yet the problem of anti-Semitism has been relevant to Kolomyya for a long time.

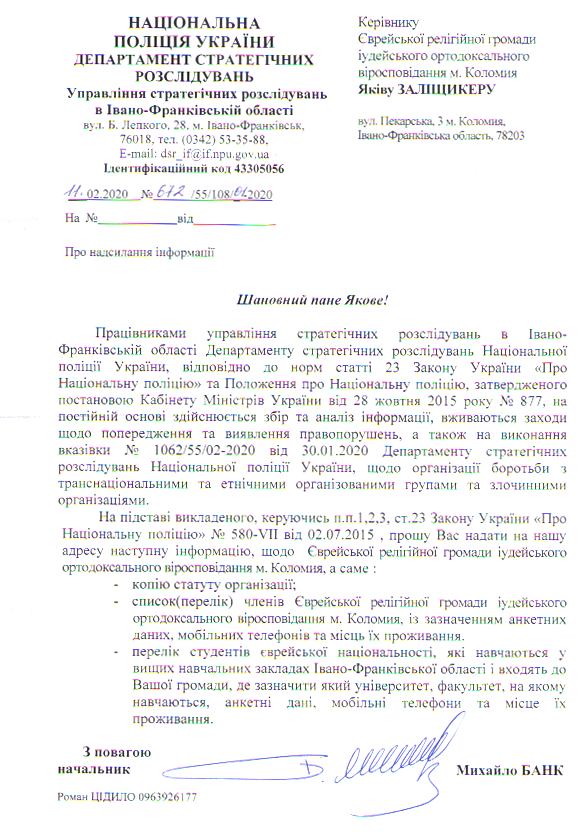

A xenophobic request

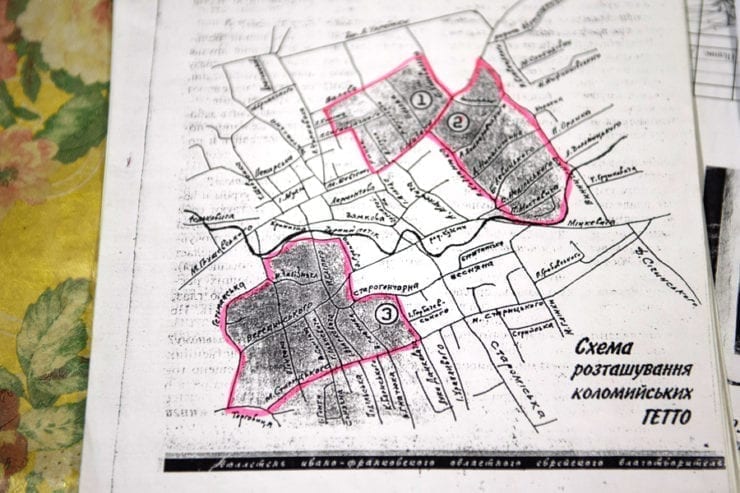

Before World War II, Kolomyya was a predominantly Jewish city where Hasidism was widespread. In 1941, the Nazis created a ghetto in Kolomyya and shot 30,000 Jews. Several thousand more were sent to the Belzec death camp. Today, only about a hundred Jewish families live in the city. They are united by a synagogue and a community led by Yakov Zalishchiker, a member of the Association of Jewish Organizations and Communities (VAAD) of Ukraine.

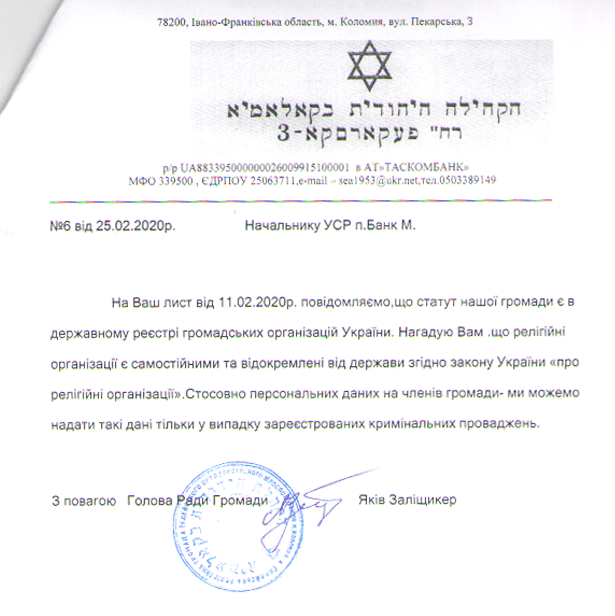

In mid-February, he received a letter from the National Police requesting a list of Kolomyya Jews in connection with “the organization of the fight against transnational and ethnic groups and criminal organizations.” Zalishchiker showed the letter to Eduard Dolynsky, director of the Ukrainian Jewish Committee, on May 9, the day of victory over Nazism.

“When I saw this letter, I was shocked, because the document is completely illegal, anti-Semitic, and xenophobic in its content,” Dolynsky told Zaborona. “This is called stigmatization. They [the National Police] did not send such a letter to Greek Catholic or Orthodox communities to draw up lists in connection with the fight against organized crime. They turned to the Jews. This indicates a deep xenophobia.”

An international scandal broke out after Dolynsky’s publication. Soon after, according to Zalishchiker, the head of the Strategic Investigations Department of the National Police of Ukraine, Andriy Rubel, and the head of the National Police, Ihor Klymenko, called Zalishchiker and apologized. Klimenko said he had initiated an internal investigation.

“We cannot understand how this happened. We are not a party to the conflict and want to understand it for ourselves,” said Svyatoslav Kukharskyi, deputy head of the Ivano-Frankivsk region’s strategic investigations department. The letter to Zalishchiker was signed by his boss, the head of the department Mykhailo Bank. In late April, some Verkhovna Rada deputies signed an appeal to Interior Minister Arsen Avakov demanding Bank’s dismissal for allegedly misappropriating protected lands near Bukovel and blackmailing local entrepreneurs, as reported by Apostrophe. On May 19th, it became known that Bank had been fired from the police.

Conflict over the cemetery

The head of the Jewish community in Kolomyya, Zalishchiker, believes that the request of the National Police may be related to the old Jewish cemetery, which has long been a source of conflict between the Jewish community and the city council. The cemetery was established in 1829, at a time when Galicia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It was located outside the city, where the tzaddik (Jewish saint) Hillel Boruch Liechtenstein is buried. During the Nazi occupation, Jews were shot in this cemetery, and under Soviet rule, tombstones were demolished and a park was built. Since then, Kolomyya has grown. The cemetery is located in the central part of the city, and the townspeople became accustomed to walking through it toward the lake. According to Zalishchiker, the locals stopped perceiving it as a burial ground.

In 2009, the Jewish community decided to restore the cemetery and turn it into a memorial park. On Zalishchiker’s instructions, the cemetery was fenced off, which, he says, “began to bother everyone.” In late 2015, unknown individuals set fire to a chapel near the tzaddik’s grave, after which the community set up surveillance cameras there. Cameras soon recorded several young men in hoods smashing 42 tombstones with crowbars. These were representatives of the local branch of the far-right organization “Right Sector”. In March 2016, someone punctured the wheels of Zalishchiker’s car.

In February 2017, representatives of far-right organizations, without the consent of the city administration, erected a cross on the territory of the Jewish cemetery in memory of fallen UPA fighters. In 2018, local authorities proposed to rename the cemetery a memorial square, without mentioning its Jewish history. In both cases, Zalischiker is conducting court proceedings.

The tombstones are another story. Slabs from the Jewish graves can still be seen in some courtyards in Kolomyya. For example, back in 2016, the yard of the house at 5 Franka Street, where the Gestapo was located during the occupation, was covered with slabs. The local administration, Zalischiker says, is not interested in removing the tombstones that are still scattered around the city and returning them to the Jewish community.

“In Kolomyia, we [the Jewish community] are like a bone in the throat,” Zalishchiker told Zaborona. “There are 62,000 people in the city and only fifty radicals, but for some reason everyone is afraid of them and dances to their tune.”

Anti-Semitism or land issue?

Vyacheslav Likhachev, a researcher of far-right movements and coordinator of the group monitoring the rights of national minorities, believes that the conflict in Kolomyya is most likely not grounded in anti-Semitism.

“Commercial and land interests of various local groups converge on the site of the cemetery,” Likhachev told Zaborona. “It is claimed that both non-Jewish victims of Nazism and Ukrainian nationalists killed by the Soviet authorities are also buried in this area. The Jewish community is trying to defend what it considers its heritage and somehow ‘memorialize’ it. City officials say Ukrainian nationalists were also shot. And Jews are perceived as those who are trying to privatize a place that is important not only to them. In such situations, there is an objective basis for conflict, and anti-Semitism is often built on top, but it is not necessarily the cause.”

According to Likhachev, letters requesting a list of community members and their contact details from the National Police were received not only by Zalishchiker, but also by representatives of other communities, such as the Azerbaijani and Polish communities. “Someone must have decided to compile a list of members of different communities,” says Likhachev, “and this is unreasonable, absurd and illegal, of course, but there can be no question of special prejudice and pressure on the Jewish community in this case.” Zaborona asked representatives of these communities to provide photo letters or confirm such a request from the National Police. But they ignored our request.

Zalischiker considers the request not a manifestation of anti-Semitism, but “the illiteracy of the police officers who wrote it.” “The Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast Department told me that they had had clear instruction from Kyiv, from the Department of Strategic Investigations, to write such a request,” he said. “We asked them to show us the paper with this decree to analyze the original source, who did it and why, but so far we have not been provided with it.”

Anti-Semitism is growing, but in a microperspective

According to Vyacheslav Likhachev, in 2019 there was an increase in anti-Semitism compared to 2018. “Until recent years, from 2016 to 2018, the number of cases of vandalism and anti-Semitic violence in Ukraine decreased,” he said. “Perhaps it is because the president is Jewish.” Such propaganda as ‘the Jews came to power to take away our land’ is actively dispersed, for example, in connection with the law on the sale of agricultural land. However, all this falls short of the number of incidents, which was, say, 15 years ago. In 2005–2006, there was twice as much vandalism and 10 times as much violence as there is now. That is to say, in the macroperspective, anti-Semitism is not growing.”

The state does not monitor public sentiment, and the police rarely prosecute on the basis of anti-Semitism. Polls on this topic yield contradictory results, so it is difficult to say whether anti-Semitism in Ukraine has really decreased. Eduard Dolynsky believes that hatred of Jews is present in the country at various levels: “among officials, law enforcement agencies, among civil society.”

However, Dolynsky does not consider this to be the main problem, “because anti-Semitism is everywhere.” “The main problem is the reaction of society and law enforcement agencies, the reaction of denial. In Ukraine, it is customary to say that we do not have this [anti-Semitism], it is all Russian propaganda. This indicates that there is a problem and they are trying to hide it, which is unreasonable. “

Translated by Kate Garcia