Visual storytelling producer Ivan Chernichkin and photographer Stas Ostrous visited the former private equestrian sports complex “Atlant” in Staryi Saltiv, Kharkiv region. With the beginning of the full-scale invasion, its owner took all the documents and fled to Russia, leaving the horses to fend for themselves. Local police officers, a groom, and farmers are making tremendous efforts to save the animals from death.

On the road from Kharkiv to Staryi Saltiv, there is almost nothing left to remind us of the recent fierce fighting between the Ukrainian army and the Russian occupiers. The fields have been harvested, and the destroyed houses are hidden by yellow-green autumn leaves that have not yet fallen. On the side of the road, villagers sell apples and pumpkins. Driving into Staryi Saltiv, I notice a dressed up couple going down to the basement of the ruined church of Vira, Nadiia, Liubov, and their mother Sofia for a service. Our car stops on the opposite side of the road from the church, near the “Dough” café. The local public transport stop combines and satisfies all aspects of life: a transportation hub, a number of convenience stores, a pharmacy, household chemicals store, and a draft beer spot.

But that was before the war. Now only the “Dough” café, currency exchange, and pharmacy are open. All other shops were destroyed by shelling and completely burned out. After the de-occupation of Staryi Saltiv, a Point of Invincibility and a modular Nova Poshta postal service office opened on the square. Another unchanged pre-war artifact is a display of dried and jerky fish. The aquatic fauna of the Siverskyi Donets is hung on the roller shutter of the closed Beer Station store. The seller sits at a self-made folding table and asks people not to park in front of the counter, as cars block the business from potential customers.

The Church of Vira, Nadiia, Liubov, and their mother Sofia in Staryi Saltiv. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

Two policemen are drinking coffee at a table outside a café. When they see the photographer Ostrous, they greet him and immediately ask: “What kind of coffee would you like?” Returning with the coffee, one of them immediately starts talking about the life of the Starosaltiv community, his work, and the problems of the horses from the “Atlant” Equestrian Club that they take care of. It all sounds like some kind of official report, so we have to interrupt him to get to know each other and make the conversation less formal. “Well, let’s finish smoking and go see everything,” the policemen agree.

Denys Kerpek and Dmytro Novytskyi are police officers of the Starosaltivka territorial community. They are in charge of 21 settlements in the Chuhuiv district. Dmytro is a tall and charismatic 37-year-old man. He is a local, and spent his childhood and youth in Staryi Saltiv. Novitsky smokes a lot and speaks little: only to the point. With his semi-grey Spanish beard and charismatic reserve, he could easily be the hero of an American Western.

His partner Denys Kerpek, on the other hand, resembles a good guy movie character who tries to help everyone, no matter what it takes. Denys met the war in Vovchansk and spent 40 days under Russian occupation with his wife. After escaping from there through the fields, he immediately returned to police service, and, like Dmytro, participated in the de-occupation of the Kharkiv region together with the military.

Dmytro Novytskyi. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

Denys Kerpek. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

After the liberation, the Starosaltiv community elected Denys Kerpek and Dmytro Novytskyi as police officers through a competition. For three months, they were trained under the International Criminal Investigative Training Assistance Program (ICITAP) in Vinnytsia. Together with American instructors, they learned how to investigate crimes, underwent first aid training, and studied traffic rules in conditions as close to reality as possible. A community police officer is basically a sheriff who combines the functions of a criminalist, investigator, district police officer, and road inspector. These people should be as close to the community as possible, know its problems and needs, and always be visible, not just sitting in the police station.

“It was a great experience. I would go to such training again,” says Novytskyi. “I’ve never been an investigator or a criminalist, and here people with different experiences and knowledge share it and complement each other.”

On both banks of the Siverskyi Donets, the water stretches to the skyline. The fall trees on the horizon are drowning in a blue haze. Lone fishermen sit on the shore, and swans swim closer to the opposite bank. Looking at this landscape, you realize that before the war it was a real resort where many people came to relax on weekends. Now Staryi Saltiv looks more like a ghost town with ruined houses, destroyed technical college and kindergarten, and problems with utilities.

A house destroyed by Russian shelling in Staryi Saltiv. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

Residents of Staryi Saltiv on a street in the city. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

A mourning wreath on the fence of a kindergarten destroyed by Russian shelling in Staryi Saltiv. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

We are heading to the “Atlant” equestrian sports complex — at least that’s what it was called before the war. It is hard to say how to call this place now. Turning off the asphalt road, we drive a few hundred meters through sand, fields overgrown with wild shrubs, and pine forest. Among the tall, dry grass, the turn to the complex is almost invisible, and the half-destroyed silhouettes of buildings on the horizon look abandoned. A green KAMAZ truck is waiting for us here. Denys gets out of the car and goes to talk to the man in the truck — a local farmer who has brought hay and 20 bags of oats for the horses.

After entering the territory, the cars are immediately surrounded by a dozen horses. They rub against the cars and lick the windows, preventing the passengers from getting out. And when we manage to do so, the animals begin to study the guests with fear and curiosity. While Denys and Dmytro are unloading oats from the KAMAZ, farmer Serhii hastily tells us that it was Denys who asked him to help with the horses’ food. They have known each other for almost 15 years, and Denys has always helped everyone: cats, dogs, people, and now he has taken up horse rescue. Serhii has a herd of dairy cows in the neighboring village of Kyrylivka. He heard about “Atlant” before, but this is his first visit. “I often see these horses grazing in the fields. Sometimes, when I’m driving home from Kharkiv to Kyrylivka, they cross the road in a herd, not letting the car pass. You signal to them, but they don’t respond.”

Police officers Dmytro Novytskyi (left) and Denys Kerpek unload oats. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

Before the war, “Atlant” was a self-sustaining private production and entertainment business. Depending on the season, it employed 7 to 15 people, had livestock of about 200 pigs, and raised rabbits and chickens. They used their own machinery to cultivate the fields where they grew food for the animals. But the main decoration and pride of the complex has always been horses. It was the horses that attracted the majority of visitors to “Atlant”. Some people came here to ride with their children in a horse-drawn carriage, others to ride on horseback. Horses were also used for weddings and various celebrations. The complex had a dining room and a large recreation area.

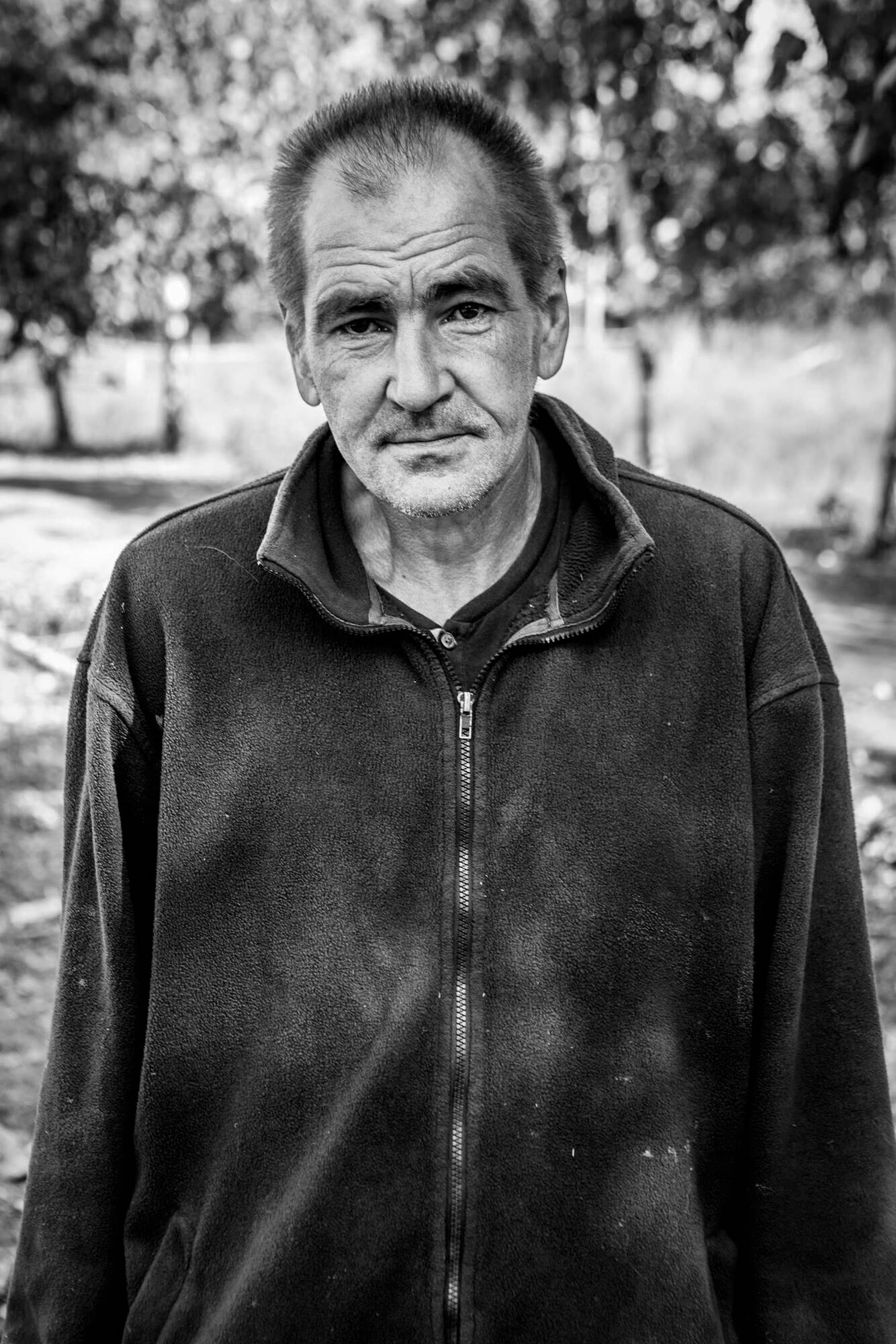

Now there is only Oleksiy, the groom, who has been working here for 12 years. He looks a little over 60. He is a tall, thin, gray-haired man with a face as if made of plasticine, deep-set eyes, and a hushed voice. He says there were a few other employees here on February 24, but they all fled during the active warfare. “I’ve been here for 12 years, and this is my 13th year. All the time… Both when the Russians were here and when our army came. The owner left the place a year ago, but I stayed. I can’t leave the horses. I’ve helped half of them through labor, you know?”

Oleksiy, the groom at the “Atlant” equestrian sports complex. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

Oleksiy does not want to talk about the previous owner of the complex. He only says that his name is Oleksandr Solodko. He knows that the Russian military came to him, and he had tea with them. On the next day, after they left, Solodko collected the documents on the complex and the horses and left for Russia. “He is not a suspect, nothing like that. He is an ordinary citizen, somewhere abroad. Nobody knows where exactly, but he was traveling through Russia. Did he stay there, or is he already in Europe? Who the hell knows,” explains Kerpek. “The complex has been abandoned. Thank God there is a person who understands how to do things here, and he is working. And we help as much as we can in all matters.”

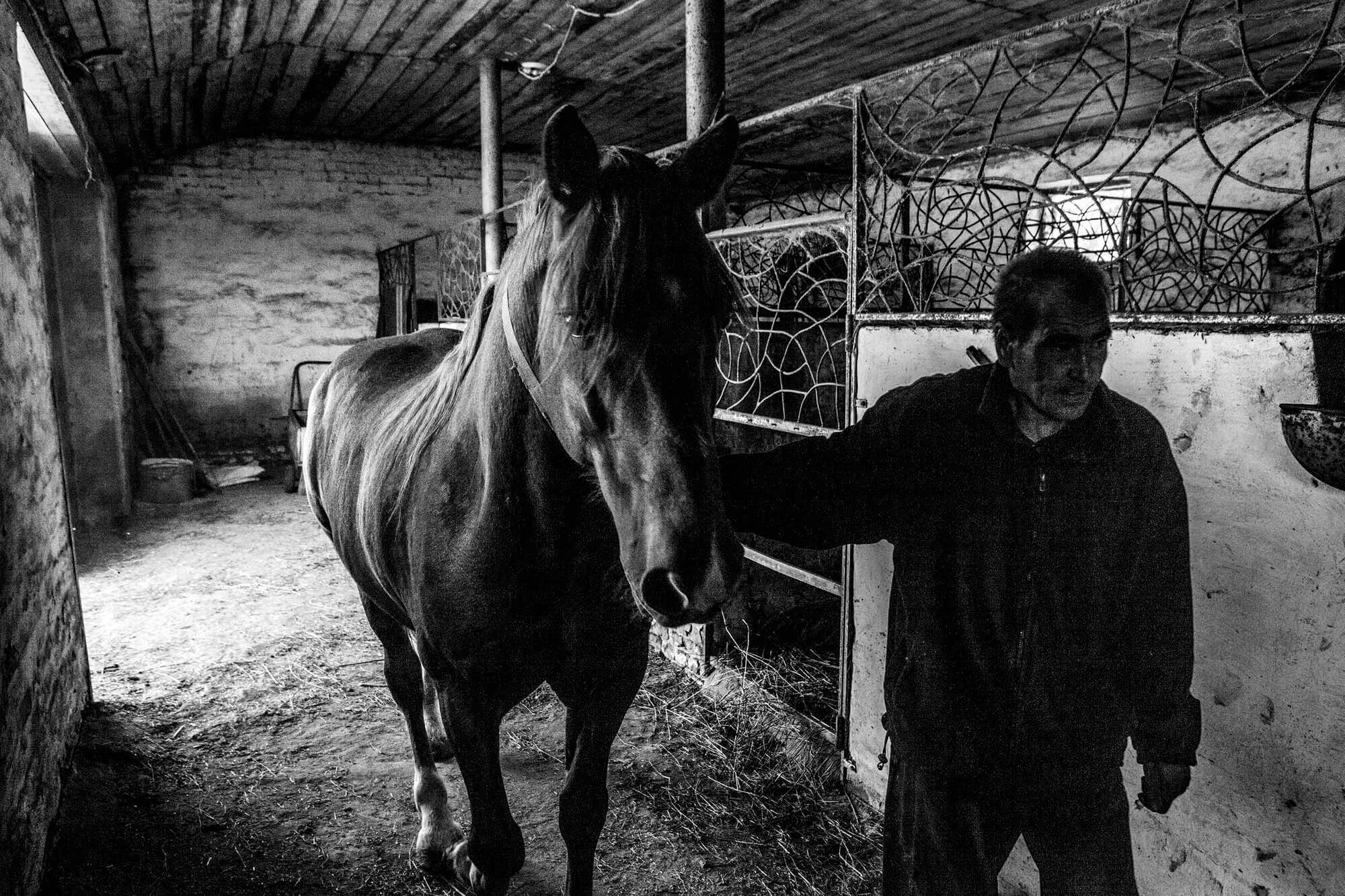

During the active hostilities in the Kharkiv region, shells hit the territory of the complex 33 times. One stable was completely destroyed, the other was damaged. One mare was wounded and her 5-month-old foal died. When the shelling started, Oleksiy would first hide the horses in the stables and then hide in the cellar himself. When the attacks stopped, he put out the fires and saved the animals as best he could. After the de-occupation, problems with looting and robbery began. One tractor was dismantled for spare parts, some agricultural equipment was stolen, and the power lines were cut. Since September last year, he has repaired the roof of the damaged stable and covered the broken windows with plastic. But he still needs to brick the walls and prepare the place for the winter as much as possible so that the animals won’t freeze. “We have bricks, but I don’t know how to lay them. In addition, we need cement and sand, which I don’t have the money for,” says the groom.

The stable destroyed by Russian shelling. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

Damaged and looted agricultural machinery. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

A horse in the stable of the “Atlant” equestrian sports complex. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

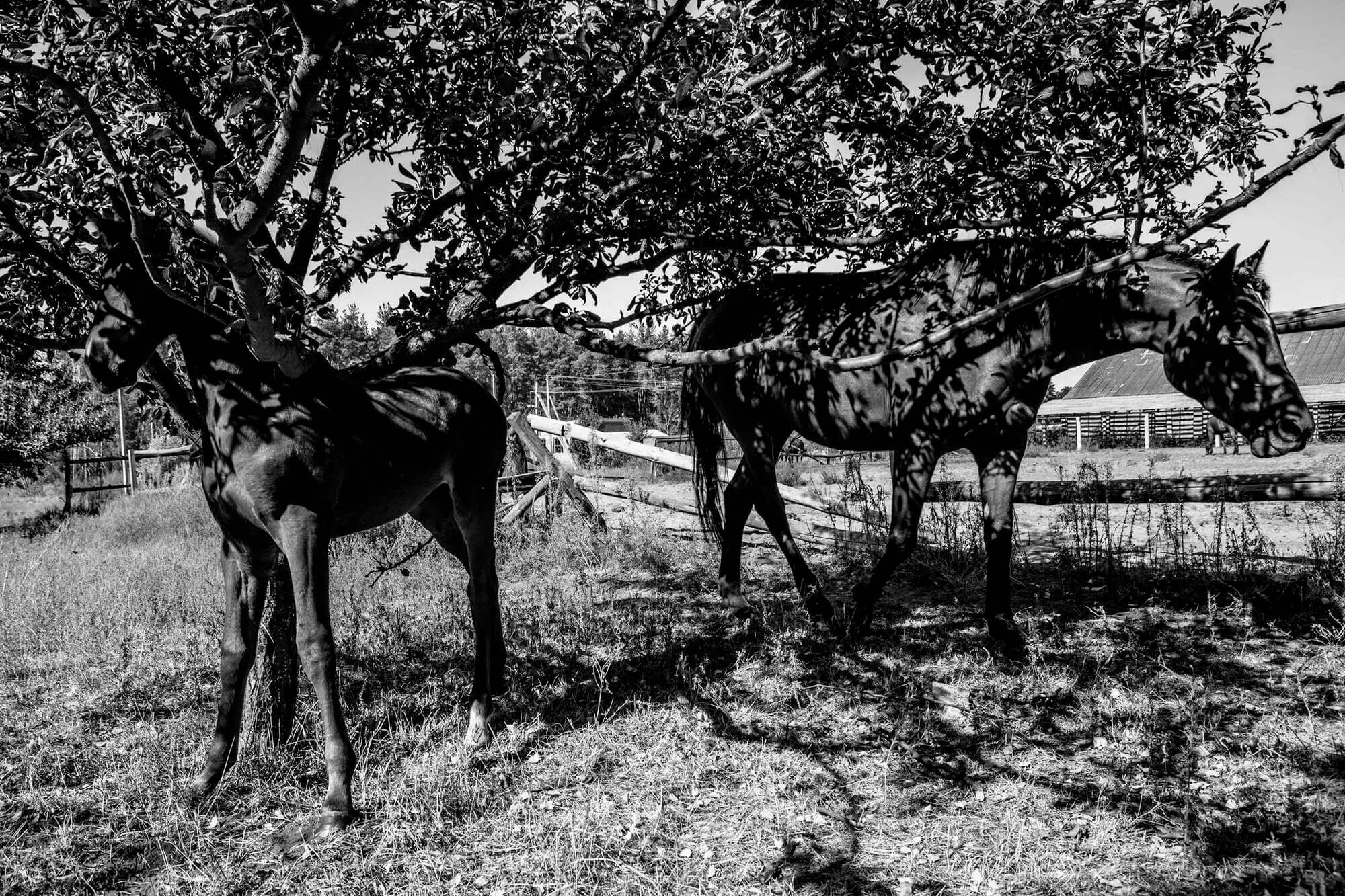

Speaking about problems and needs, Oleksiy always talks only about animals and the complex, completely ignoring himself. The mares and foals spend the entire warm season on free-range, only the stallions need to be fed. But when the grass on the fields runs out, all 28 horses will have to be fed. The oats and hay brought by Serhii should last until about mid-December. The groom does not know what will happen after that. But food is not the main problem for the animals; they also need veterinary care, vitamins for joints, hoof, and mane care.

“Maybe some [of the horses] need a doctor to come and see them, to give them vaccinations. I see that they walk, but how do they feel inside? The doctor understands what their internal state is, or how a horse is with a leg, right? They seem to be fine, alive. Again, a mare scratched herself somewhere, and I have nothing to treat her with. Maybe they need to be dewormed, but you have to buy all this stuff. And it’s not cheap, one ampule syringe costs 1,200 UAH, and there are 28 horses,” says Oleksiy.

It is not just Oleksiy who dreams of a new owner, but also police officers Denys and Dmytro. They note that it would be an ideal solution if there was a person who would take control of “Atlant” and be able to restore the complex. Instead, the police, worried about the lives and health of the animals, are forced to hold explanatory talks with meat procurers who periodically come to the complex to try to buy horses for meat.

Denys Kerpek (right) and Dmytro Novytskyi petting horses. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

Oleksiy leads a horse into the stable. Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona

But it is very difficult to resolve this issue from both a practical and legal point of view. The equestrian club is private property, and no one knows where the owner is. Therefore, it is also unknown where all the documents and passports for the horses are. Now the fate of the 28 “Atlant” animals is entirely in the hands of two Starosaltiv sheriffs who are keeping them safe and Oleksiy, the groom. The farmers of the Starosaltiv community also partially help the animals, but unfortunately this is not enough, because there are still utilities — electricity and water bills, which make up a significant part of the expenses.

We say goodbye to Oleksiy and take a walk around the complex. A young mare stands near a pink stable, pockmarked with shell fragments, as if painted by Banksy. Young stallions roam in the old apple trees, and somewhere in the grass, away from strangers, a one-and-a-half-month-old foal hides behind its mother. The horses surround us from all sides as soon as we approach the car. They poke at us with their long, graceful muzzles. The photographer and I regret that we forgot to buy them some treats — apples and sugar. Dmytro and Denys shake Oleksiy’s hand, and he reminds them about vitamins for the horses and diesel for the tractor. “Time to saddle up,” one of the policemen jokes, and we head back to Kharkiv.

Photo: Stanislav Ostrous / Zaborona