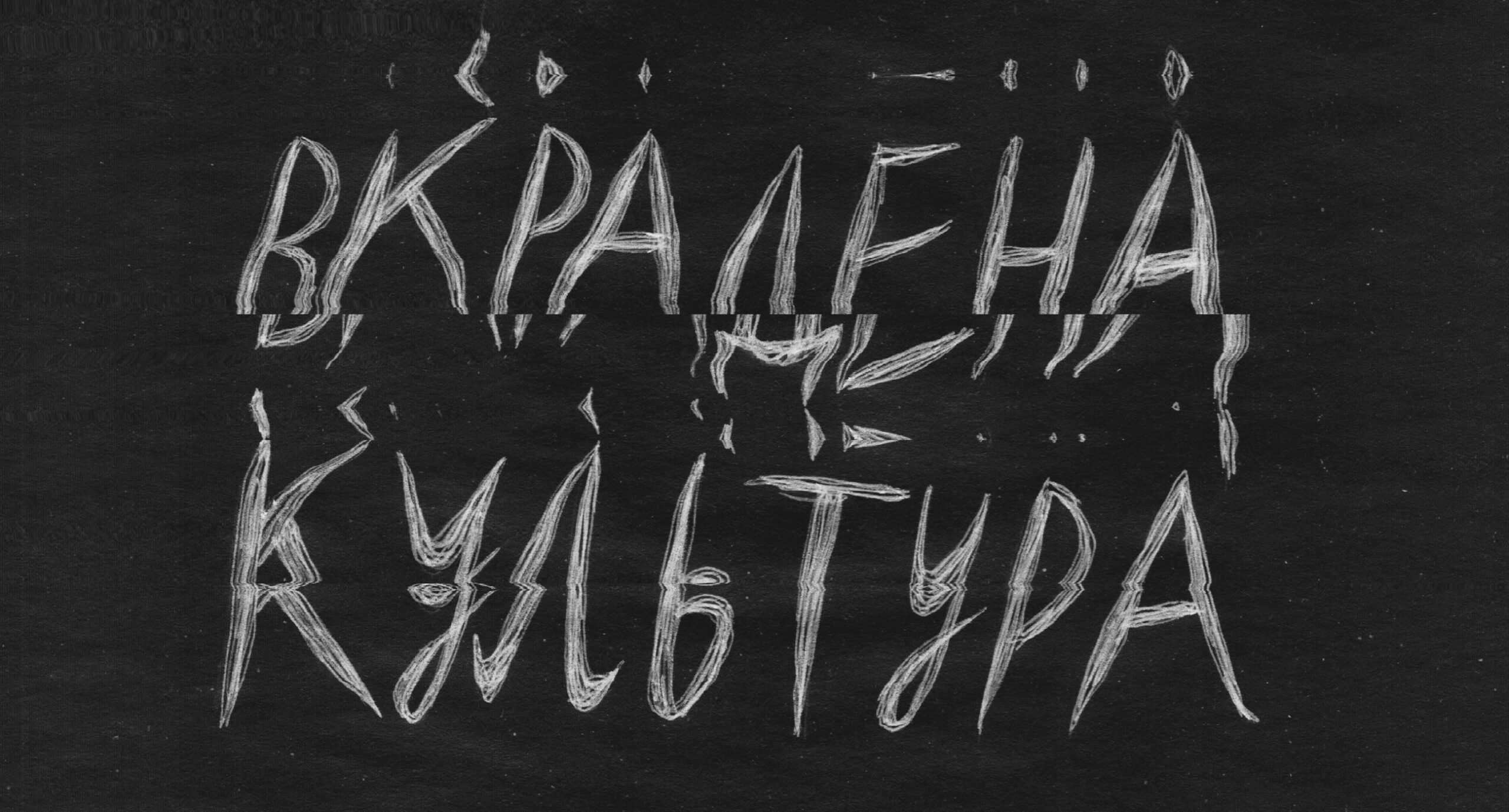

The majestic culture is majestic at the expense of 22 republics. The curator, Katya Taylor, explains in her column about Russia’s colonization of Ukrainian culture and how museums can help counter it

Musealization (and appropriation) of foreign cultures is an ancient colonial practice that began in the 18th century. Most former empires, from France to Britain, renounce colonial cultural policy and return stolen exhibits. Still, Russia considers itself an empire and denies Ukraine authentic culture, ascribing it to itself. At the request of Zaborona and Volya-Hab, a project studying the colonial practices of the Russian Federation, curator Katya Taylor tells how the war accelerated decolonial processes in the artistic environment, why Malevich was considered a Russian artist until February 24, and whether Ukrainian culture will be of interest to the world after the war.

The British Museum became the first modern museum in history. It opened in the middle of the 18th century, at the height of the first industrial revolution. Its collection consisted of archaeological finds in the private collections of several wealthy sires and war trophies from countries colonized by the British Empire. For almost three hundred years, the British Museum was considered the pride of the British nation for some reason, although most of its exhibits were stolen.

Of course, history knows the example of the Romans who fought with the countries of North Africa and brought looted goods to install in the central squares of their cities. But the musealization of the stolen began precisely with the British Museum — the largest in the world at that time. The very idea of a museum as a system of collection, cataloging, and public presentation appeared not so long ago — at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries. The second museum of the modern format was the Louvre. The basis of its collection was mainly works of art, but not only: various trophies can (were) found here as well.

In both cases, British and French, museums were created at the height of the empires when there was so much loot that something had to be done with it. Of course, this is not the only reason. At the end of the 18th century, several important events took place at once: the first wave of industrialization and the associated urbanization; the democratic movements in France that led to the French Revolution and, as a result, the opening of the Louvre to all comers, not just royalty.

Visitors sit in front of Benin bronze plaques (removed from what is now Nigeria) controversially placed at the British Museum in London on February 13, 2020. Artifact restitution claims against the museum include the return of Greece’s Parthenon sculptures and Egypt’s Rosetta Stone, among others. Photo: © David Cliff / SOPA Images via ZUMA Wire

Before that, no one particularly thought it unethical to show the loot. There was no public discourse that would encourage such reflections. Even after the collapse of most of the world’s empires, it took almost a century to start openly talking about the fact that everything that the largest archaeological museums of Europe is proud of and on which their publicity is built — has been stolen.

For the first time, the protection of cultural values and preservation of the rights of nations to cultural property was mentioned in the 1970 UNESCO convention. It could not have happened without the democratic movements of the 20th century: the struggle for people’s rights and, in particular, for the rights of African Americans, the recognition of their cultures, the impact of colonization on them, and the discussion of cultural appropriation. Repatriation is the next step to the equality of people and their cultures, which would not be possible without all the previous ones.

The British, for example, are implementing entire projects about their feelings of guilt. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam does something similar, telling an alternative history that took place in the colonial countries at the same time as the processes in the colonizing countries. On paper and in the media, we see many statements about the return of colonial exhibits, including a statement from the Dutch National Museum of World Cultures, which promised to return all artifacts from the colonial collection. The British Empire, in its turn, ended its existence not only formally and legally but also culturally, publicly acknowledging its role in the appropriation of foreign cultures (although it still has not returned many values to the colonies). No one knows whether the world’s leading museums will soon return the collections, nor is it known what to do with the artifacts whose provenance remains unknown.

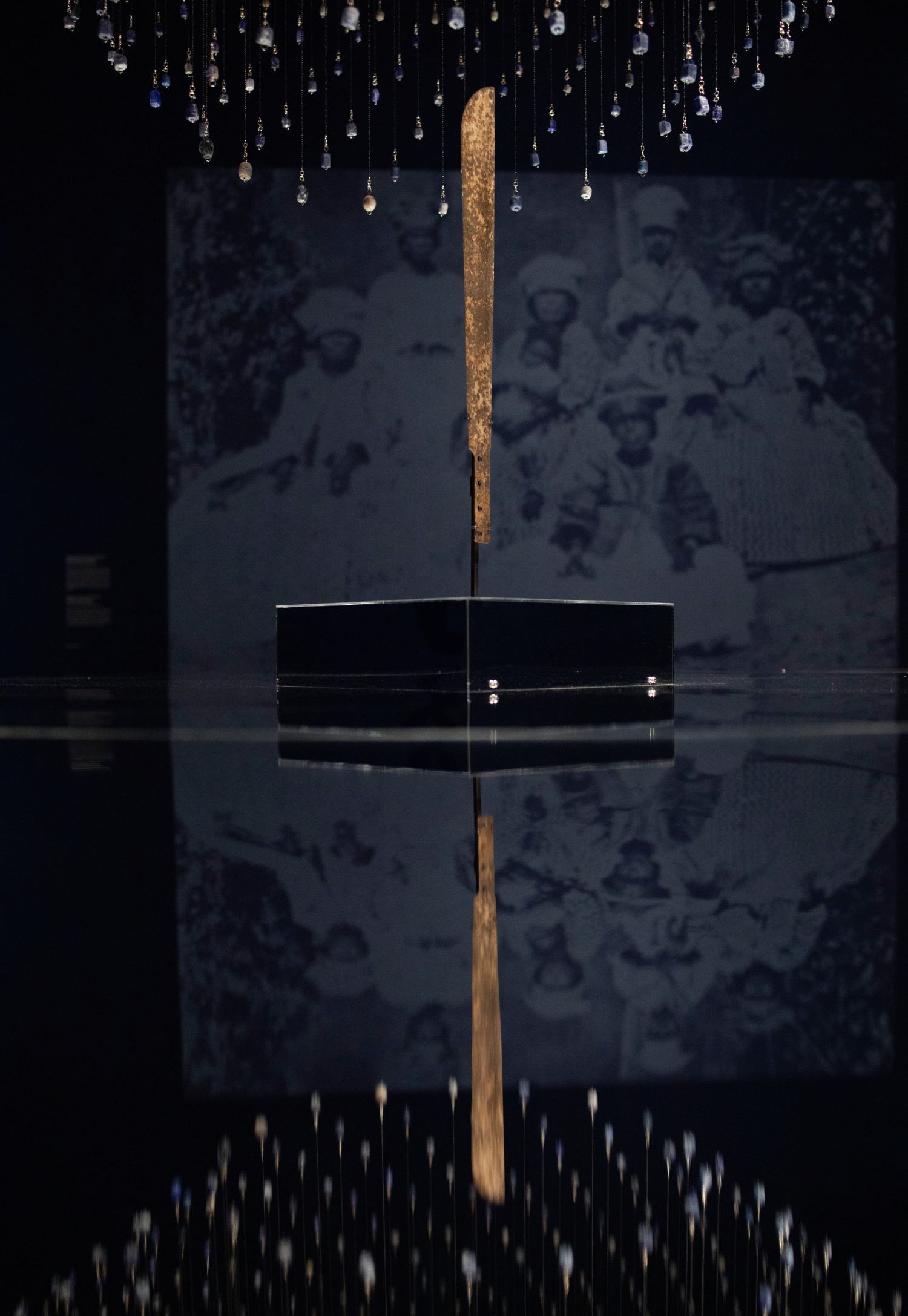

A machete used to cut sugar cane is displayed at the Slavery exhibit at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, on May 17, 2021. The exhibition is devoted to the history of Dutch participation in the international slave trade. Photo: Peter Dejong / AP Photo

But the reinterpretation of the colonial past only happened to some. It did not happen with the Russian Empire, which, as before, pulls the looted blanket over itself and does not recognize the advantages of other cultures, except for the “Great Russian.” Post-colonial optics do not exist in Russia because the empire has not ended its existence. All its attributes remained: centralized and unchanged power, territorial expansion, cultural propaganda, and the imposition of the Russian language. For a post-colonial framework to emerge, it is necessary to recognize the captured countries as equal, having the same rights and freedoms and being able to exist separately. The post-colonial discourse erases the myth of the great Russian culture — great at the expense of 22 republics, involuntary participants in its formation.

Over the centuries, Russia encroached on Ukrainian culture and called Ukrainian writers and artists “its own.” Because of the close neighborhood, Ukrainian artists could indeed study or work in Russia, but does that make them Russian artists? And does this make them people who shape “Russian culture”? There are two strategies here: appropriating talents and broadcasting their assets to the world as Russian heritage. Maybe that’s why the world believes in the “great Russian culture” because it doesn’t think about what this culture consists of or how much it is specifically Russian. Let’s take the Russian avant-garde, a trend that developed in Russia in the first half of the 20th century on a par with the European avant-garde. Still, at the same time, it existed, as it is customary to believe, somewhat hermetically. Among the artists of this movement were Ukrainians — Ekster, Bogomazov, and Malevich. Almost nowhere is it mentioned that they are Ukrainian artists; in catalogs and monographs, it is mostly stated that they were born in the Russian Empire. Often not a word is said about the country of birth.

Oleksandr Bogomazov, “Prison”, 1914. Public property

Interestingly, the Russian avant-garde, in contrast to the European avant-garde, is an artificially constructed form that exalts one culture and levels others. The European avant-garde assumes that the artists are Europeans from different countries and different cultures, and they are united by, in fact, avant-garde views on art. Russia does not recognize this: everything that is liked is called Russian, and everything that is not is destroyed. The Executed Renaissance is one example of how a “great culture” can be constructed. After all, only those who can sing her odes remain alive.

But if there is a Russian avant-garde as a geographical phenomenon and not as a form, is there a Ukrainian one? Should it sound solo, or is it part of the European? We did not build a museum of Ukrainian modernism, where, in addition to the museum collection, there could be an archive, a library, a platform for research, and a lecture hall. An institution that would start studying this phenomenon, which would undoubtedly help put Ukrainian art on the Western cultural map, is the homework we still have to do.

Ukraine found itself in the center of the world’s attention not only thanks to a full-scale war but also thanks to a unique culture that no one knew about. It all started with exhibitions of modern artists, live concerts of musicians, and screenings of Ukrainian films at international film festivals. Over the past few months, the European focus of attention began to rapidly shift toward history with an open question: what do Ukrainians stand for if what we see in modern times is so attractive? It cannot be the case that the Ukrainians are nothing, as Russia claims. After all, if what they show and do today is so exciting, what was there in the past?

Ukraine has never been so interesting to the world’s intellectual community. For decades, Ukrainian culture was considered an adjunct to Russian culture. The world had no task to figure it out. It was the war that became the catapult for Ukrainian culture and identity. After the breakup of Yugoslavia and a series of wars, the world also began to take an interest in Balkan art – or rather, the cultures of individual countries, finally giving them a voice. Today, exhibitions of Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian artists are held all over Europe. European interest in Balkan art grew, but it is essential that each country separately had to rebuild its identity after the war and draw attention to itself.

European institutions, which only yesterday did not want to rename the explanations of paintings in their museums to “born in Ukraine,” today are included in the process of reappropriation, introduce guides in the Ukrainian language and support the idea of decolonization of Ukrainian culture in every possible way. However, the problem with reappropriation is that we cannot knock on the doors of every single museum and ask them to change the information in the archives and expositions. For this to happen generally, it must be evident to the world’s museums that it cannot be otherwise. As for example, it happens with French or German culture. Do we emphasize this systematically? And will we be interested in the European decolonial project without war? Whether Western institutes will be loyal to us for a long time depends only on us — on what exactly, how often, and how well we are ready to export.

This explainer was created as part of Volya Hub, an international network that promotes education about Russian colonialism and its consequences. Join using the hashtags: #VolyaHub #ВоляХаб #RussianColonialism #РоссийскийКолониализм

Illustration: Maria Petrova / Zaborona