For more than 20 years, Vasyl Vorobets has been working as an artist at the Rodyna Cinema in Vinnytsia. Using colored paint on a white prepared canvas, which is an ordinary second-hand bed sheet, he draws the titles of contemporary films.

In the era of film cinema, the position of a film set designer was in every movie theater. But today, Vasyl is perhaps the last keeper of visual art, which reminds many people of their childhood.

Zaborona visited the artist, who, like the protagonist of Giuseppe Tornatore’s film The New Paradiso Cinema, made friends with a projectionist as a child and was able to watch evening screenings for adults through a hole in the cinema booth.

One of the oldest cinemas in Vinnytsia, Rodyna, is located in the city center, near European Square. To get to the renovated building, you have to go through the arch of a brick house with three large movie posters hanging on the wall. On the white fabric stretched over a wooden frame, the names of current screenings for children and adults are printed in colorful paints: “Guardians of the Jungle 2: Around the World,” “The Lion King Jr.,” “Fallen Leaves,” “Marvels.”

The entrance to the Rodyna cinema in Vinnytsia. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

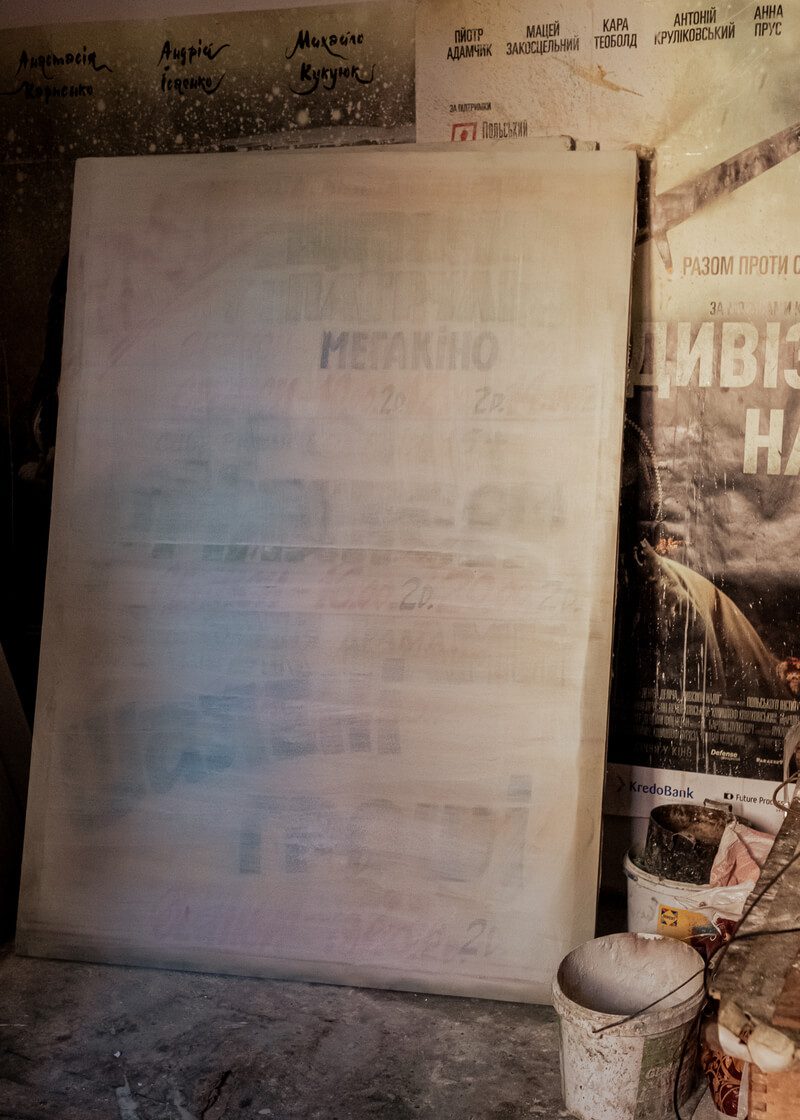

In the art workshop on the second floor of the cinema, Vasyl Vorobets is preparing the white canvas of a poster to write on it with a green gouache brush the name of the upcoming world premiere of the film “Napoleon”, and talks about his childhood in the village of Mizhrichchia in Ivano-Frankivsk region.

“There were artists in my family on my father’s and mother’s side. So the word “artist” sounded magical to me as a child. I used to run away from school and go to Morshyn. Walking in the park among the vacationers of the resort town, I would stop behind a street artist and watch his work for hours. That’s how I became interested in painting.”

Vasyl Vorobets in the cinema’s art workshop. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Vasyl traces the outline of the title “Napoleon” with dark paint, adds the hours of the movie sessions, and continues:

“The projectionist at the movie theater in my village knew that I liked to draw. In exchange for watching movies for free, he offered to help him. So, as a schoolboy in the late 1960s, I was already writing movie titles and time with colored inks on thin paper of movie poster templates. I used to ride the projectionist’s bicycle with a handful of drawing pins around the village and hang the painted posters on trees. In return for my work, he allowed me to watch evening movie screenings through a hole in the cinema booth, to which only adults were allowed with a 20-kopeck ticket.”

Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

In addition to paints, brushes, prepared canvases, and other art supplies in the artistic mess, the walls of his studio are decorated with completed paintings. Among them are the Cossack Mamai on resting, being watched by a Jew from behind a tree, and Vanka in an earflap hat, as well as illustrations of Ukrainian proverbs. In one of Vasyl’s most important paintings, he depicted two children in white clothes sitting in the middle of a village lawn. The boy is blowing away a dandelion, and the girl is watching him carefully.

“This picture is sweet and dear to me because it is my childhood and the children’s game “Grandpa or Grandma”. If everything is blown off the dandelion, then it becomes bald, and this is the grandfather, and if something is left on the flower, then it is the grandmother.”

On the table in the corner are many rolled-up movie posters. You can see the names “Pamfir” and “Avatar 5″ among them. Behind them, a black-and-white photo of Liubomyr Huzar appears on the wall. Vasyl used it to depict the hero of the documentary “Liubomyr. Being Human”. For the premieres of films about historical figures of Ukraine, the artist makes color portraits of their characters. Among them are Bishop Yosyp Slipyj, healer Zakhar Berkut, composer Mykola Leontovych, and opera singer Solomiya Krushelnytska. And there is a portrait of a soldier hugging a girl in an embroidered shirt, dedicated to the Day of Defenders of Ukraine.

In the cinema’s art workshop. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

In the cinema’s art workshop. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

A movie theater that has the status of a municipal cinema also receives movie posters printed in a printing house. They usually hang on the facade of the building. When asked why they still paint posters, which are the highlight of the place, Vasyl adds:

“Sometimes they [printed posters] don’t come. And the older generation wants to see these posters. They grew up with them. Three years ago, after the cinema was renovated, the posters I made were canceled. For about two weeks we had only printed posters. Residents of the city and visitors to the cinema noticed this and raised the issue with the city authorities. After that, the painted posters returned.”

Posters of the Rodyna cinema. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Posters of the Rodyna cinema. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

The cinema used to have 27 employees. Among them were 2 painters, an advertisement cleaner, a man who delivered advertisements, and a carpenter who made frames. Now 13 people are working here, and Vasyl is doing the work for five positions that no longer exist. He finishes drawing the first block of the future poster and goes to the renovated foyer of the cinema to hang the printed posters:

“There used to be drawings of fairy-tale characters all over the wall, as well as an aquarium with fish. However, during the renovation, the walls were painted over and the aquarium was taken away. Many visitors remember and ask about the aquarium, which is no longer there. It’s nostalgia. Just like the painted advertisement: a person grew up with it, it was their childhood, so now it seems good to them.”

Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona