Recently, the town of Novhorodske in Donetsk region reverted back to its original name – New York. In October, the town held an international literature festival. Zaborona journalists visited the town, fell in love, and are now encouraging others to visit as well. Here’s what you need to know about Ukraine’s very own New York – and its residents.

There is no lack of towns like New York in the Donbas. High unemployment, poor environmental surroundings, an intermittent water supply, and all close to occupied territory – from which these towns are often shot.

Just ten thousand people live in New York. They’re tucked into hills just four kilometers from Horlivka – one of the bigger cities in Donetsk region, which has been occupied by pro-Russian forces from the so-called ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’ since 2014. The town’s borders are shaped like a fire hatchet: the handle goes to the south, towards occupied Donetsk, and the tip points to Horlivka. For all those ten thousand people, there are just four schools and one boarding school, but once the students graduate, they’re then forced to travel to a bigger city to continue their education – and, as a rule, they don’t return.

Yet there’s still something that separates New York from the rest of the Donbas: a rich European history. Ever since the old Novhorodske returned to its historic name, local residents have started to feel hopeful for change.

A view looking out at Russian occupied Horlivka and the biggest house in New York.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

A symbolic refueling

27-year-old Kristina Shevchenko shows off the gas station, also named New York, in the center of the town, next to a phenol factory owned by Ukrainian oligarch Rinat Akhmetov’s Metinvest company. The town’s economic life is centered around this factory. Kristina says that this unusually named gas station was built in 2004 – that’s when she learned that her hometown of Novhorodske once had a completely different name.

Kristina Shevchenko is in fact the person who became the face of New York of the Donbas – and in February of this year, she spoke at a Parliamentary committee hearing about the necessity of returning the town to its historical name. The committee supported her idea, and voted ‘yes’ in July.

Today, Kristina teaches Ukrainian and Ukrainian literature in New York’s 17th school. She has a complicated relationship with her hometown. Prior to the war, she took classes at the Horlivka Pedagogical Institute, in the foreign languages department. She would travel from then-Novhorordske to Horlivka each day. She was twenty years old when parts of Donetsk region were occupied by pro-Russian forces and she was transferred to Bakhmut, along with the of her evacuated university.

A mosaic by Ivan Litovchenko and Volodymyr Pryadka, entitled “Revolution”, 1966. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

After she finished her studies, Kristina explains that she ran into a typical problem of youth living in the periphery of Ukraine: finding work was hard. She left to find work somewhere else. She worked as a grocery clerk, as a nanny, as a tutor in Turkey, the Russian interior, and in Ukraine’s larger cities.

“I went and understood that this wasn;t for me: the bustle of big cities was exhausting,” Shevchenko says. “During all these jobs, I thought, ‘Why am I doing this, if I have a career and I can work doing what I trained for and what I wanted to be? But when I returned, I understood that [in Novhorodske] there was no development, and limited space in which to grow.”

In the end, Kristina was asked to teach in the same school she had graduated from. There, she met the teenagers of the town, and in 2019, she created the NGO ‘Initiative-taking Youth of Ukrainian New York.’ That kicked off one of the most important initiatives of the town’s modern history.

Kristina Shevchenko and volunteers from the “Initiative-taking Youth of Ukrainian New York” organization.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

A short history of New York

New York is divided into two halves by the Phenol railway station: the side closer to Horlivka is considered “novhorodske” (new city – trans.), the new part of New York, appearing first during the Soviet Period. The other side, going from the phenol plant in the direction of the Donetsk highway, is considered to the “old town.”

“Old” New York was built by Germans in the mid-19th century, who had arrived in what was then Imperial Russian territory to create a new settlement. This was a colonial movement spurred on by the edicts of Empress Catherine the Great, 1762-1763. She allowed foreigners to travel to southeastern Ukraine in order to develop the land there, build factors, and fill up the Empire’s coffers – and for this they were entitled to benefits and allowances. German Mennonites – a Christian Protestant movement – were the most common settlers.

According to historians, in 1878, several families of German settlers bought around 35 hectares of land surrounding the Kryvyi Torets River from Russian noblewoman Princess Natalya Golitsyna, and founded their colonies there – forming the landscape of the modern Donetsk region. New York was one of these colonies, though historians aren’t sure why it was named as such – likely because of some American ties, as the German settlers sometimes traveled to that country.

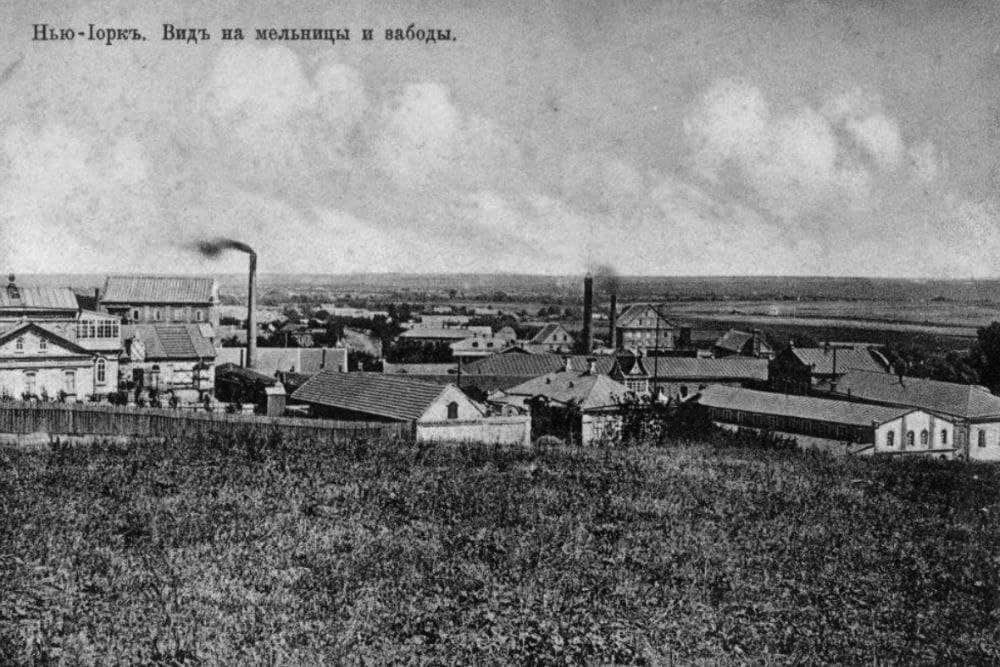

New York at the turn of the 20th century. Photo provided by the “Ukrainian New York in Donetsk region” society

At the start of the 20th century, Germans began to be forcibly evicted from these colonies. The first wave of eviction occurred after the 1905 revolution, when the Empire’s government decided to purge the workers responsible for organizing labour strikes across the country. The second wave of expulsions occurred after the Bolshevik victory in the 1917 revolution: the colonists were expelled as ‘representatives of the bourgeois class.’ The last wave took place during World War 2, when Josef Stalin ordered the expulsion of all German Mennonites, accusing them of collaboration with the Nazi regime, and banned them from returning for 25 years. The expulsion was conducted over several days in the winter of 1941 – the families were put on a cargo train at the Phenol station and deported to Kazakhstan.

The ruins of the future

The photographs of New York at the start of the 20th century showed the town to be a lively, business-oriented place with numerous plants and factories. On these photographs, one can see the pipes of six steam mills, which produced flour for the whole district, and the machine-building plant of German colonist Jacob Niebuhr, which produced self-designed innovative equipment for agriculture and creameries. One can also see the brick factory of Jacob Unger, which produced bricks and roof tiles for the towns of what is now known as the modern Donetsk region.

Here’s the center of New York at the start of the last century: a place with a two-story cooperative store with its own bakery and a large pharmacy, across from which stands an imposing bookstore and hotel, next to Peter Dick’s mill. The central road is paved with flagstones, while crowds of local residents scurry along the streets.

This New York hasn’t existed for a long time: the hotel has transformed into a crumbling facade, while the bookstore had been destroyed even prior to World War 2. Peter Dick’s mill fell into ruin and was sold off to a private buyer several years ago – after which public access to the mill was closed.

The town square where the hotel, pharmacy, bookstore, and Peter Dick’s mill were located in the mid-20th century. Photo provided by the “Ukrainian New York in Donetsk region” society

The town square where a hotel, pharmacy, bookstore, and Peter Dick’s mill were once located, modern.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

The only building that has been restored from the ruins has been the cooperative store once run by Aaron Tissen. Local residents, along with the former town head Mykola Lenko, found the money for its reconstruction – approximately $65,000 from the U.N. Development Programme, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and Metinvest. The former store has been turned into the “Ukrainian New York” historical-cultural center, where visitors can see artefacts and traces left by the old town.

Aaron Tissen’s old store is now the “Ukrainian New York” historical-cultural center. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Nadezhda Hordyuk is also fighting to restore these ruins – she’s a teacher and speech therapist at the kindergarten and specialized school for children with special educational needs. At the start of 2017, she created the “Ukrainian New York in Donetsk region” initiative, which attempts to raise awareness about the town’s history. She loves explaining how old Novhorodske had primarily European roots.

“I work on the initiative at night,” laughs Hordyuk. “The war brought its own corrections: previously, I worked only on my professional career, published academic papers, but [in 2014] I understood that you can’t simply live in your own vacuum. When I saw that people, covered with the flags of a foreign country had entered the town, I suddenly couldn’t breathe. And when our town was freed, I began to help the volunteer battalions with food and clothing and decided that we needed to take our residents, intoxicated by Russian propaganda, out of this fog and tell them the history of their native land.”

Nadezhda Hordyuk

Nadezhda Hordyuk was one of the people who defended Peter Dick’s mill from demolition and managed to get the building recognized as a regional cultural memorial.

“When the head architect of Donetsk region came to look at our mill, he said, ‘You can easily build a Mennonite Pirohovo (a well-known Ukrainian historical park recreated as an ancient Ukrainian village – trans.) here,” says Hordyuk. “There are a good deal of artefacts left behind which could be used to recreate the German center of New York.”

Peter Dick’s mill. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

The people of New York

New York is surrounded, vice-like, by the occupied territories. A mere four kilometers separates the town from a checkpoint with military dugouts. Periodically, pro-Russian forces send their ‘hellos’: in September, a drone threw down some mines onto a small military base in New York. The residents say that they fall asleep every night to the sound of gunfire.

Unlike it’s American counterpart, the Donbas New York has little to brag about: it’s harder to live here than in most Ukrainian cities. The only wealth that New York has is its people, who are unwilling to abandon this place darkened by war and poverty. They’re attempting to bring its ruins back into shape, and give its history a voice.

At the start of October, New York held an international literature festival, held at the House of Culture of the phenol factory – the center of town life for its residents. A plaque at the building’s entrance commemorates its construction – 1950, a year from when Soviet authorities would rename New York to Novhorodske, in order to remove any association with the U.S., in the midst of the cold war between the two then-superpowers.

International literature festival. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

The festival was organized by Viktoria Amelina, whose husband was born in Novhorodske, but who, like many, left after graduation. His parents were also Novhoroske natives, and sometimes returned to the town. Amelina says that this festival became a homecoming for her, and the opportunity to create something for those that live in modern New York.

“All of us – whether we’re in the west or the east [of Ukraine] – lack the ability to see and love ourselves,” says Amelina. “You need the right mirror. With this festival, I wanted to say that the real Donetsk region is very beautiful, delicate, touching and stubborn, vulnerable and strong simultaneously, and that here [in New York], people play [Queen’s] “We Are the Champions” on the accordion, and the locals sing along.”

Viktoria Amelina

The founder of the “Initiative-taking Youths of New York”, Kristina Shevchenko, shows us an abandoned German cemetery on a hill on the west side of the town. There are several marble pedestals installed on the graves of the German colonists – most of which lie destroyed on the grass. Yet one has recently been restored and cleaned. That one is a memorial to the soldiers that freed New York. However, instead of the historic name of the town, the Soviet name is written there instead – Novhorodske. Shevchenko says that she wants to fight this oblivion.

The view of the phenol plant from the old German cemetery. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

When the New York youth activists gathered for the first time, remembers Shevchenko, everyone talked about wanting a celebration: “We’re sick of being in the grey zone.” The organization now has about twenty members. Kristina watches her town from a hill, standing on a stump near the cemetery, and says that there’s a lot of work to do now: she wants to restore the historic buildings, clean up the park and local stops, build good roads and open a literature cafe. In her words, she used to not believe in the possibilities of change here – but now does.

“We one thought that it would be great here [on the hill] to put up our own Statue of Liberty,” says Kristian Shevchenko. “Then we decided that that would be inappropriate, because this is a completely different New York, with different traditions. Now we want a structure here that would shine rays down on the whole town. Of course, this would be in peacetime. First, the war needs to end.”

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona