At the end of March, Russian troops began to withdraw from the Kyiv region, and now living in the occupied towns and villages is gradually being restored. On the streets of Hostomel, Borodyanka, Makariv, Andriivka, Bohdanivka, and Katyuzhanka you can see small crowds of people. These can be volunteers who came from Kyiv to clean the streets from the consequences of hostilities, or local residents who line up to receive humanitarian aid. In addition to destroyed houses, burned equipment, and destroyed communications, Russian troops left behind the remains of missiles, mines, grenades, unexploded shells, and ammunition. New fences and cozy yards are damaged by tanks. Deep trenches stretch like a snake through yards and gardens and hide under the foundations of houses as if giant moles had visited here.

Photographer Pavlo Bishko spent a week in the Kyiv region and collected the stories of locals who are trying to understand the extent of the destruction and are learning to live anew.

On February 23, Hostomel resident Nazar Petruk and his friends went on vacation to the Carpathians. On the way to the mountains, they were spending the night in Rivne, when at four in the morning a frightened sister called him: “We have more than 30 helicopters flying here, there are shootings everywhere. We don’t know what to do.” Her brother advised her to join him in Rivne as soon as possible. She was there in 15 hours.

“We stayed in Rivne for 2 days, when we realized that we had nothing to do here. All relatives and friends were in Hostomel, mother was in Kyiv. We needed to do something, ”says Nazar. Then he returned to Hostomel to volunteer.

Destroyed house. Hostomel, April 15, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

In the first two days after the return, it was still possible to safely take out the wounded and those who were hiding in the basements. After the bridges were mined and fighting broke out on a nearby street, evacuations could only be made through the fields.

“People needed medicine. When the mayor of Hostomel opened a pharmacy for us, we could deliver medicine on foot to people under fire,” says Nazar. “We often had to make difficult choices. One day we came to an old woman with a shrapnel wound to the lungs. We knew we couldn’t save her. There was no hospital to take her there, and we could not carry her two kilometers across the field, because she would die. “Leave her, because that’s the end,” said her daughter who was nearby.

Traces of blood in the shot car of Hostomel’s mayor Yuriy Prylypko. He was killed by the Russian military while delivering medicine and food to residents of the Pokrovsky residential complex. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“When the green corridors were opened, my brother and I tried to take everyone out,” Nazar continued. “In this way, the entire nursing home was evacuated. But we could not evacuate one old man who was dying. He remained there together with five corpses.”

-

Temporary grave of 86-year-old Kateryna Yuriyivna Chernenko, who died from shrapnel wounds in her own apartment. Hostomel, April 15, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

On March 5, Nazar and his brother were driving down Universytetska Street in Bucha. The brother was driving a white car with a Red Cross sign, and Nazar was sitting behind the driver.

“We were driving through the woods when I heard a shot, and a bullet flew between my left ear and shoulder. I immediately fell into the seat thinking that my brother was gone. Shots from afar continued. The brother began maneuvering right and left until the car met a tree. Here I thought again that my brother was dead. But he was only wounded in the head. One of his eyes was bloodshot and the other was badly swollen. He saw nothing. I told him where to go, and we managed to escape,” says Nazar.

Nazar’s brother was lucky: a sniper bullet hit only the scalp, leaving a 5-centimeter mark.

-

Nazar Petruk shows a photo of his brother Zakhar, a volunteer who was wounded in the head by a Russian sniper. Hostomel, April 15, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

Nazar still continues to volunteer. Yesterday he brought medicine to an old woman. He wondered if she needed anything else. She cried.

“I don’t need anything, guys,” she said. “My daughter was shot. When she saw the Russian military was coming, she rushed to the cellar. Her three daughters were sitting there. She only managed to close the door from the inside, but 8 bullets caught up with her through that door. Her body slid down to the children.”

-

Anzhelika Volovych, librarian from Kyiv. Together with the Vperti volunteer association, she helps to clean the village. Makarivka. April 12, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko -

Destroyed position of Russian troops. Andriivka, April 12, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

During the occupation of Bucha, dozens of bodies of civilians killed by Russians were brought to the territory of the Church of St. Andrew the First-Called. Here they were laid to rest in a mass grave.

The morning of April 13 over the church grounds is cloudy, windy, and rainy. To date, 57 bodies have been exhumed from the grave. Today the exhumation continues. At the entrance to the churchyard, soldiers stand and silently let groups of journalists through. There are dozens of them here from all over the world. Police, prosecutors, and exhumation experts are discussing something. A crane has already been installed to pull the bodies out of the pit.

“Yesterday, three more burnt bodies were dug out from under a birch tree 20 meters from the mass grave. They said they were mothers and children,” said an Israeli photographer.

Oleh Doroshuk, a resident of Bucha, also came to the place of exhumation. He is one of those residents who survived the occupation and participated in the burial of people near the church.

-

Exhumation on the territory of the Church of St. Andrew the First-Called. Bucha, April 13, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“Once I was coming home from my parents. They live nearby. Meanwhile, the occupiers were breaking into shops and offices. They stopped me, tied my hands with tape behind my back, wrapped a scarf around my face, also wrapped it with tape, and put me against the wall. I stood there for four hours,” says Oleh.

-

Partially cleaned Vokzalna street where the Armed Forces destroyed a convoy of Russian military equipment. Bucha, April 13, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“Do you see the red house [bordering the church territory]? These are my parents’ neighbors. A family of migrants from Donbas lived there. They fled the war eight years ago and bought the house two years ago. On March 5, they decided to leave Bucha. They were accompanied by a family from the next house – uncle Oleh and his wife. They left in two cars, were about two kilometers away, when a convoy of vehicles with the letter “V” drove out towards them near the Chornobyl Park. They moved to the side and stopped in the so-called road pocket to let the column through. They were shot. The first car caught fire. There were two boys in it: Klym, 4, and Matviy, 10, and their 34-year-old mother, Margaryta. Only the father survived, although his leg was torn off.”

In the second car, says Oleh Doroshuk, only “uncle Oleh” was killed and his wife was wounded in the shoulder.

“And the worst thing is that the family from Donbas has a summer gazebo in the yard, with this letter V on it. The same as on the tanks that shot them,” Oleh continues.

“The youngest, Klym, should have been 5 years old today. You know, the names of the dead children are purely Bandera style: Klym and Matviy Chekmarev. This way the military directly defended the Russian-speaking. Everything goes in classic Russian style. Their bodies were not allowed to be taken away for a long time. It was only on March 28 that I took them from the place of execution to the mass grave. And yesterday they were exhumed.”

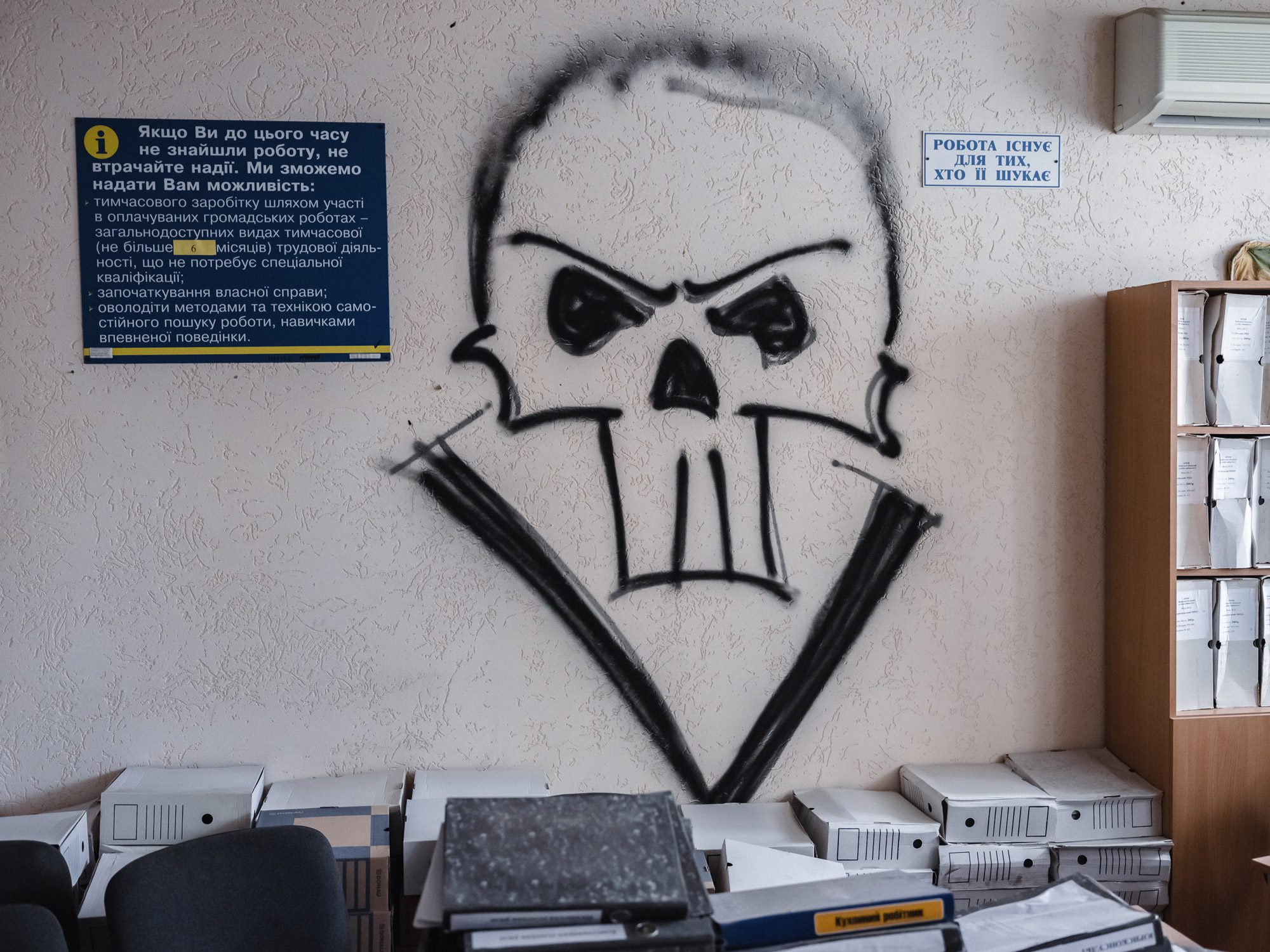

“Death to Bandera” – this inscription was left by the Russian military on a house in Velyka Dymerka village. April 14, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

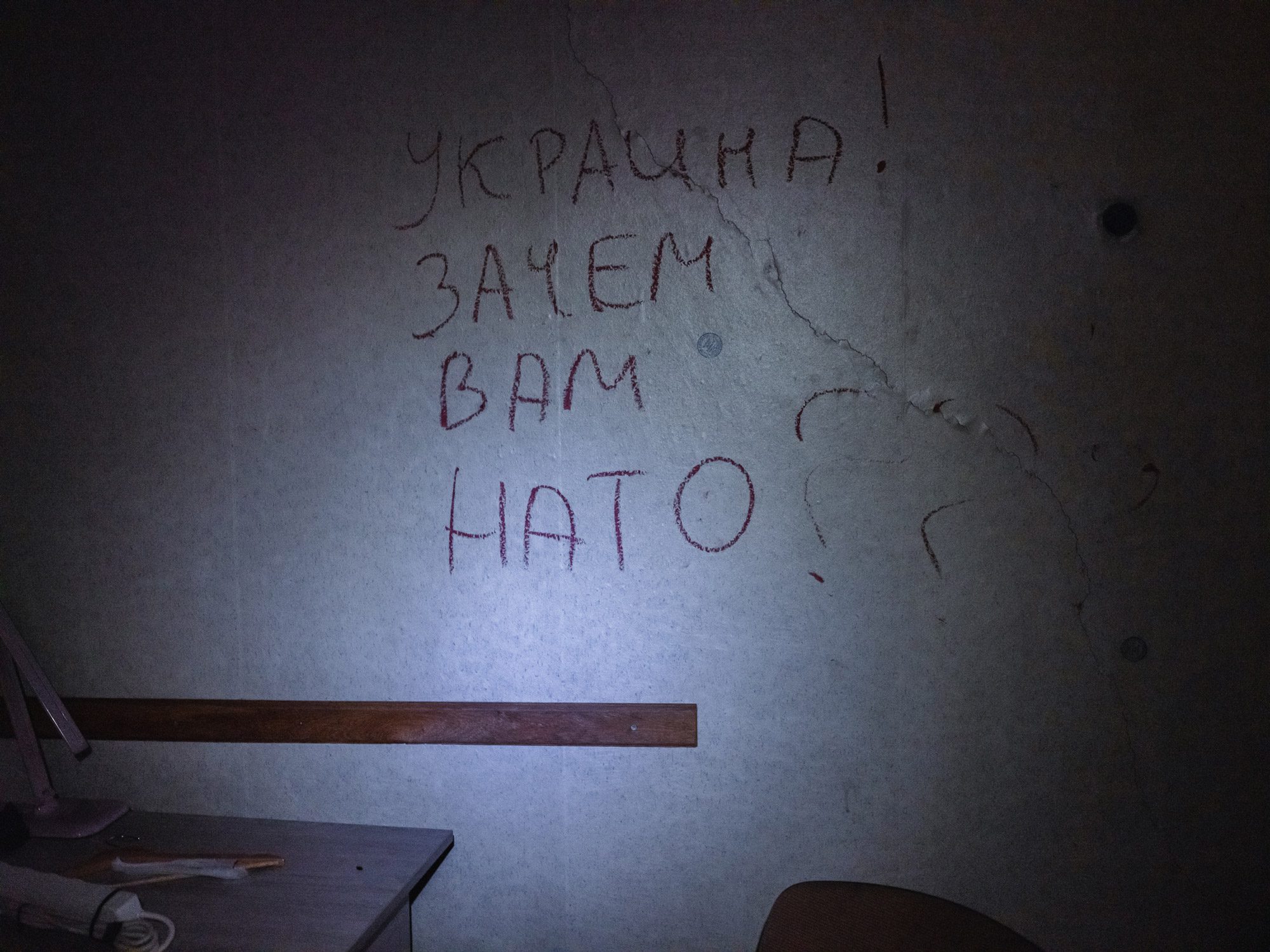

“Ukraine! Why you need NATO??” – the inscription on the wall of the room where the Kadyrovites headquarters’ was located. Yablunska street, Bucha. April 13, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

School number three is located on Vokzalna street in Bucha, where many Russian vehicles were destroyed. Broken windows, looted classrooms, scattered things, dismantled computers. There are many green wooden boxes of shells and dry rations in the schoolyard.

-

Physics classroom of school No. 3 in Bucha. April 13, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“There was a combat position here in the schoolyard. They shot mostly in the direction of Irpin,” says the school cleaner Tamara. “I have been working at this school for seven years. And my grandchildren study here. This school is a life to me. All these repairs were made by my colleagues. Our school was considered the best in Bucha and the district. Olympiads and meetings of directors were held here. And now it is unknown what will happen next. My soul and heart are for what they have done here.”

-

Borodyanka, April 17, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

Petrovsky street in the village of Velyka Dymerka suffered the greatest damage. Almost every second house here is completely destroyed or damaged. A group of volunteers is bustling in one of the yards. They are briskly clearing from the rubble the area in front of Svitlana’s house. The roof and ceiling of her house, where she lived with her husband and son, were severely damaged.

-

Svitlana in front of her house. Velyka Dymerka, April 14, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“My house needs to be dismantled. There is no ceiling there,” says Svitlana. “Everything fell, everything crumbled. We will rebuild it. My sister [her house is on the next street] also bears huge losses. Her house and barn were burned down. She was left without anything at all – without even a spoon and, sorry, underwear. And a rocket flew into my daughter’s apartment in Irpin. She lived there for only a year. The rocket flew through her two-room apartment and caught fire in the apartment next door.”

A neighbor told Svitlana how the three Russians walked around the village. They looked at the houses and said: “We will not touch this house, it is so old. We’ll go looking for something rich and modern.” And when they get to a better house, they say, “Oh, we have to damage it a little, because they live too well.”

-

Borodyanka, April 17, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

Ten people lived in the house of the Kazmirenko family in Borodyanka during the occupation. These are neighbors and acquaintances who have nowhere to live after the heavy bombings. Mykola Kazmirenko is a radio amateur. He lit his own house with the help of a solar panel, which was taken away by the Russian military during the departure from Borodyanka.

In his yard, he shows a disassembled and neatly folded radio antenna. When the Russian military searched his home twice, they confiscated his antenna, radio, and solar panel, which he used when the lights went out after the Borodyanka airstrikes.

-

The Kazmirenko family: Lyudmyla, Ivan Harashchenko (Lyudmyla’s father), Mykola, and Viktoria. Borodyanka, April 12, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“Why don’t you leave?”, the Russian soldier asked Mykola, he recalled.

“Well, how do you imagine it: I will leave everything, I will leave my house, especially since there is a roof, there are walls. The windows flew out there, I’ll put the glass in, and everything will be fine.”

“If I were you, I would leave,” the soldier said.

“And where to?” Will you let me go? ” Mykola asked.

“No, I won’t.”

“Where should I go?” Mykola asked again.

“To Russia through Belarus.”

“I don’t really want to go to Russia,” Mykola replied.

After the Russian army left the city, Mykola Kazmirenko found his antenna undamaged at an abandoned Russian checkpoint near his home.

-

Residents of Andriivka are cleaning the village after the withdrawal of Russian troops on April 12, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko -

Andriivka, April 12, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

The family of Anatoly and Lyubov Shpak from the village of Velyka Dymerka was forced to evacuate from their home because of a Russian tank.

“My husband and I were in the house when a tank entered our yard,” says Lyubov Shpak. “We left our house through the kitchen window on the opposite side of the yard. We spent two nights in sub-zero temperatures in a neighbor’s greenhouse. On the third cold night, we made our way to our summer kitchen. At that time, Russian soldiers lived in our house. We were rummaging between the closet and the wall when the occupier came in and asked if anyone was there. My husband replied that we were here, and this was our home, and asked if we could stay here until morning. We were allowed to spend the night. The next day, another neighbor took us to his house.”

-

Anatoly and Lyubov Shpak in the bedroom of their house. Velyka Dymerka, April 14, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

Lyubov goes to the second floor of her burned house. There are guest and children’s rooms. Each is pierced through with large-caliber bullets. One of them broke through three walls. The last destroyed obstacle for the projectile was the closet of the couple’s grandchildren.

-

A wall and a closet in a children’s room in the Shpak family house were pierced by shelling from a Russian IFV. Velyka Dymerka, April 14, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“When Russian troops left the village, at least twice they shot at the second floor of our house from their IFV. After that, a fire broke out on the first floor in the bedroom. Since there were a lot of clothes, the fire went up pretty quickly. We ran with the neighbors and tried to extinguish it. Although we managed to save the roof and walls of the house, we lost everything we had gained here since 1998. Only six years ago we finished furnishing the house.”

-

School No. 3, Bucha. April 13, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko -

House in Velyka Dymerka, damaged by the shelling. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

From the window of the Shpak family house, you can see a picturesque pond. Fishermen are sitting above the water, and Hryhoriy Polovko is working in the next yard. During the occupation of the village, a shell hit his territory, as well as the neighboring yard where his son lives.

“On March 13, a mass evacuation began,” says Hryhoriy. “Our village is very large, up to 13 thousand inhabitants. So the evacuation lasted three days. I’m a pensioner, I thought I would evacuate the children, and I will stay here until the end. Here were my friends who also have not yet left. I thought I would stay, together we will organize a “special unit of suicide bombers.” We’ll take Molotov cocktails and rush right under the tanks! To destroy at least one or two. ”

“Stop crying, I said,” said Hryhoriy’s wife Vira. “You promised not to cry. Pray for the children to be alive. Here is our Kolia now somewhere near Kharkiv. From the first day, he was in the Territorial Defense of the village. During the evacuation, he pushed us out of the house and said he would follow us. But he went to the military registration and enlistment office as a volunteer.”

-

Hryhoriy and Vira Polovko in the living room of their house after the Russian occupiers left. Velyka Dymerka, April 14, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“Our relatives took us to Brovary,” Hryhoriy continues. “In Brovary I was persuaded to leave and we were evacuated to the Cherkasy region. We returned home four days ago.”

“We never thought they were capable of that,” he continues. “They are a gang. A gang! They climbed into the cellars and took everything from there. And when they entered the house, they took everything they needed and then shot at the house. When most of the residents left, they got drunk and walked around the village: “Wow, this is such a rich hut, well, let’s shoot!” – and boom from the tank! As soon as one of the remaining citizen’s moves, they shoot immediately. Here my relative’s niece and her husband were driving – Russians shot them. Only a week later, they allowed the bodies to be taken away and buried.”

-

The House of the Polovko family was damaged by the shelling. Velyka Dymerka, April 14, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“And our godmother’s mother-in-law and her son died from a Russian grenade,” says Vira Polovko. “She wanted to bury them. And they [Russian soldiers] were standing in the garden and shouting: “Don’t you dare! Otherwise, you will be there too!” She left on the last day of the evacuation, and only after returning did she bury her relatives. How is it possible to withstand all this?”

“When the Russians left, the priest held up to 22 funerals a day in the village,” says Vira. “To date, about 80 people have died from what we know. Our neighbor Oleksandr was also buried in the garden. He was shot in the car, his head was blown off. And the body was not allowed to be taken away.”

-

A destroyed car near the village of Katyuzhanka. Photo: Pavlo Bishko -

Remains of a Russian missile that hit the house of a Hostomel resident. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

Five soldiers with weapons stood in a line and prepared for a simultaneous shot. Their faces are illuminated by the sun at the zenith. They are waiting for the order. A group of three dozen silent people gathered nearby. Some of them have just returned to Velyka Dymerka. On a wooden table lies a bouquet of yellow daffodils, on which a framed portrait of a man rests. A few fresh spruce cones were placed under the portrait. A woman in a black headscarf says through her tears over the coffin: “He told everyone: don’t go, don’t go. And he left…”

Exactly one month ago, on March 14, Oleksandr Stupak left his house in the center of the village and went to the outskirts, where his sister and her husband lived. Russian troops had already entered there, and battles were being fought.

“When they started bombing the village, he said, ‘I’m going to pick up Valya and Petya,” says his neighbor Larysa. But Oleksandr never reached his sister’s house. A Russian armored personnel carrier shot at his car on one of the streets of Velyka Dymerka.

“For two days we persuaded them [Russian soldiers] to let us take his body,” Larysa continues. “He also served in the military, I tell them, as well as you, he fought in the Afghan war. He never offended people. Let us bury him.”

-

Funeral of Oleksandr Stupak in the village of Velyka Dymerka, April 14, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

In the end, only one man, a neighbor and a friend of Oleksandr, was allowed to take the body. Oleksandr was buried near his house at the end of the garden. He had a wife, two sons, a daughter-in-law, and a sister.

“He loved children so much, but will never meet his grandchildren. Our Oleksandr was a very good person,” says Larysa.

Yulia Semenyuk also came to say goodbye to Oleksandr. Together with their family, she hid from shelling in the cellar.

-

Yulia Semenyuk in front of her own ruined house, where she lived with her husband and three children. Velyka Dymerka, April 14, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“The next day, after our evacuation to Novohrad-Volynsky, a Russian tank came to our yard,” says Yulia. “We were able to return home only in early April, after the withdrawal of Russian troops from Velyka Dymerka. But only parts of the burnt walls remained there.”

Under the shots of the military and the tears of his wife and daughter-in-law, Oleksandr’s body was covered with earth for the second and last time.

-

Funeral of Dmytro Bernatsky, shot in the street by the Russian occupiers. Bucha, April 15, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko -

Traces of blood in the room on Yablonska street, where the headquarters of the Kadyrovites was located. Bucha, April 13, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

“Then there was the fear of how to escape, how to hide, how to survive. And today it is an internal fear, with a growing pace of uncertainty on what else still awaits us,” said 68-year-old Iryna from Borodyanka, who recently returned to her hometown.

Iryna with her dog hid from the bombing of Borodyanka in the basement. And on March 10 she left for the Ivano-Frankivsk region.

“Vasyl Shpak and his daughter Oksana took me and 28 other migrants. They themselves were left without food, but we were fed the last they had,” she says. “We were very well received. But I wanted to go home so much – I thought I would go on foot. They tell me that spring is coming in the Carpathians, it will be very beautiful here. But I wanted to see my willow, my Borodyanka so bad. They admired nature, but it did not affect me at all. I only thought about Borodyanka.”

-

Borodyanka, April 17, 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

Irina’s dog stayed with the neighbors in Borodyanka. When Irina returned, the dog licked her and jumped for joy.

“I said: Mask, we are not to blame, there was no way to take you with us,” says Iryna. “I knew you were in a private house, there was your booth. If I had the chance, I wouldn’t leave you. I was afraid that you would run away from me somewhere along the way. And here you were at home, a Queen of Borodyanka.”

Irina feeds her dog in the central square of the city and watches as rescuers dismantle the remains of a destroyed high-rise building.

“I’m sorry for our soldiers. I would kiss their hands for the fact that they protect us, for the fact that they are dying. And he [Putin], I think, has nothing to destroy here. He has already become ‘famous’ all over the world for his deeds in Borodyanka and Bucha,” says Iryna.