The Nord Stream-2 deal recently struck between Berlin and Washington means that the much-maligned gas pipeline, intended to carry gas from Russia to Europe, bypassing Ukraine, will finally be completed. Zaborona’s Romeo Kokriatski looks into the history of the pipeline, and why the current deal is heavily criticized both in Ukraine, and abroad.

On July 21st, the United States announced that it had come to an agreement with Germany to allow the controversial Nord Stream-2 gas pipeline, running from Russia and bypassing the Ukrainian gas transit system, to finish construction.

This deal, struck between the Biden administration and German chancellor Angela Merkel’s government, promises that German companies involved in the pipeline’s construction will not be placed under U.S. sanction, an effective green light to finish the nearly–completed pipeline. Germany, for its part, has committed to a $1 billion fund for green energy development in Ukraine, as well as other energy diversification initiatives.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and U.S. President Joe Biden hold a joint news conference in the East Room of the White House. Photo: Chip Somodevilla / Getty Images

Hated by nearly everyone

The pipeline’s now-assured completion has raised hackles in Kyiv, despite assurances made in the deal that would see Germany ‘taking action’ against Russia if the Kremlin decided to use the pipeline to exert political influence on Ukraine. Dmytro Kuleba, the Ukrainian Foreign Minister, wrote on Twitter that Ukraine was invoking an article in the Ukraine-EU Association Agreement allowing for immediate consultation with Germany and E.U. on that topic, in addition to filing a joint statement with the Polish government. The statement blames the NS2 deal for creating “…political, military and energy threat for Ukraine and Central Europe, while increasing Russia’s potential to destabilize the security situation in Europe, perpetuating divisions among NATO and European Union member states.”

Yuriy Vitrenko, the head of Ukraine’s state-owned gas company Naftogaz, meanwhile, says the fight is far from over. Speaking during an interview with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, Vitrenko mentioned that Ukraine is making legal moves to block the pipeline’s operation, as stopping construction is a lost cause. “The battle has been lost, but not the war. And our war against Nord Stream-2 continues,” Vitrenko said, mentioning that if Kyiv can prove that the pipeline is not independent, according to E.U. energy laws, then it may not be able to legally operate.

Beyond the government denunciations, for Ukraine, the deal represents something of a betrayal of one of the few functioning post-Soviet democracies. Terrell Jermaine Starr, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center, mentioned that “This is an issue that goes across the region…Once you get beyond the specificities of the deal you really get this feeling from people that [Ukraine] is…one of the few nations that is unequivocally going to stand up to [Russia].”

Terrell Jermaine Starr

Opposition in Washington to the deal has been no less outspoken, with top Democrats such as Senator Bob Menendez from New Jersey publishing his own joint statement saying that the pipeline will “will strengthen the impact of Russian gas in the European energy mix, endanger the national security of EU member states and the United States, and threaten the already precarious security and sovereignty of Ukraine.” Signed by the chairmen of foreign affairs committees from ten countries in total, including Ukraine, it sets out a hard line against the Nord Stream-2 deal, mentioning how Nord Stream-2 will likely be used ”…yet another tool to pressure and blackmail Ukraine.”

The Russia reaction, on the other hand, has been jubilant – with Russian officials claiming that gas transited through Nord Stream-2 will be cheaper than via Ukraine. At the same time, the Russians aren’t entirely happy – Dmitry Peskov, Russian president Vladimir Putin’s press-secretary, commented that the Washington-Berlin deal obliges Germany to facilitate Russian gas shipments through Ukraine for the next decade, a point that the Kremlin would like to forget.

German ‘guarantees’ like the Budapest Memorandum

The most likely outcome of Nord Stream-2’s completion – assuming it becomes operational – is the loss of transit fees for Ukraine. While under the current gas transit contract, Russia is obligated to pay transit fees even in the absence of gas, that contract expires in 2024 – meaning a new round of negotiations. With Nord Stream-2 operational, however, Ukraine will have much less leverage to act.

“Russia won’t offer Ukraine anything when contract negotiation comes up,” Starr comments, and that sentiment is supported by none other than Alexei Miller, the CEO of Russia’s state-owned gas company, Gazprom. In a statement, Miller notes that “…Gazprom has always stressed its readiness to continue transiting gas across Ukraine, including after 2024, based on economic viability and the technical condition of Ukraine’s gas transmission system.”

Miller’s words, specifically when it comes to ‘economic viability’ and ‘technical conditions’, point to a Russia that is very likely to use those exact two excuses to avoid any preferential deal – for Ukraine – when re-negotiation comes up. In 2019, during the last round of gas transit negotiations, Russia linked continued transit to gas supply: something Kyiv is keen to avoid, as paying Russia directly for gas (currently, Ukraine sources gas from Europe) would effectively mean paying the same force that is currently occupying parts of its territory. Losing the gas transit contract, however, would equate to about $3 billion in losses annually for the country.

Russian President Vladimir Putin (R) and Gazprom’s chief executive Alexei Miller talk at the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg. Photo: ALEXEY NIKOLSKY / AFP via Getty Images

Germany hasn’t been blind to these concerns, at least in word. According to the text of the agreement, Germany commits to a number of initiatives – some old, some new – in order to secure Ukraine’s physical and energy security. These initiatives include Germany once again committing to the Normandy format and Minsk agreements, adhering to unbundling and third-party access for Nord Stream-2 under E.U. energy regulations, and using “all available leverage to facilitate an extension of up to 10 years to Ukraine’s gas transit agreement with Russia, including appointing a special envoy to support those negotiations.”

Importantly, Germany also promises to “take action at the national level and press for effective measures at the European level, including sanctions,” if Russia uses “energy as a weapon” or “commit[s] further aggressive acts against Ukraine”. This, despite the on-going and sustained aggression Russia has been committing against Ukraine for the past seven years, is technically intended to dissuade Russia from using gas transit as a political cudgel against Kyiv.

These guarantees, however, seem difficult to enforce. During an interview with Voice of America, Naftogaz head Yuriy Vitrenko pointed out that he doesn’t understand “…how can Germany guarantee gas transit through Ukrainian territory, if it’s neither sourcing nor supplying gas from Russian territory.” On top of this, the commitment to enforce sanctions on Nord Stream-2 being used as a political weapon by the Kremlin reminds him of a similar so-called guarantee that Ukraine was once subject to: the Budapest Memorandum. “Ukraine has already had the Budapest Memorandum, which was considered to be a guarantee of security. Budapest Memorandum number 2 is not something appealing to us,” Vitrenko said.

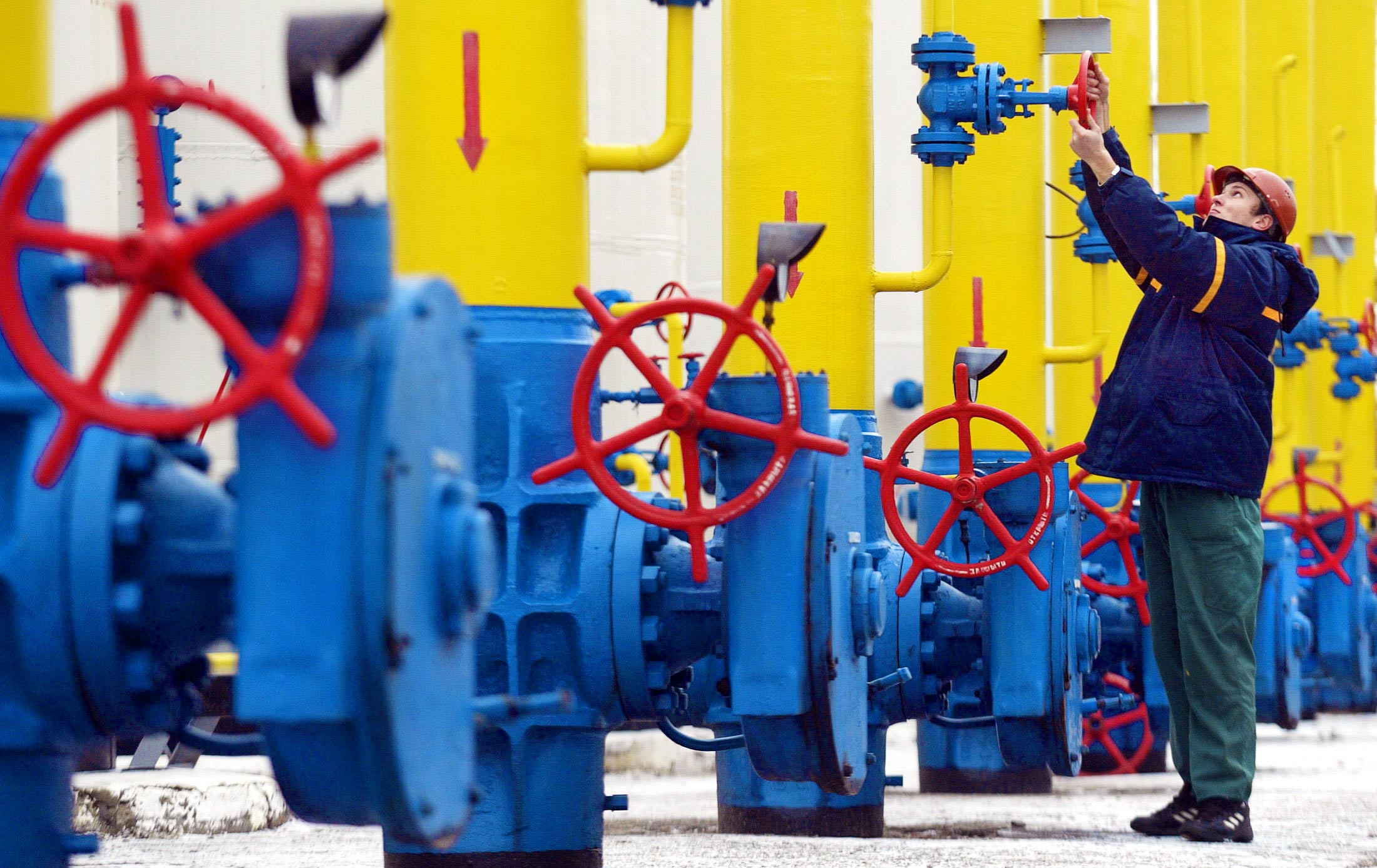

An employee of Ukrainian gas firm UKRTRANSGAZ checks equipment in the village of Boyarka, near Kyiv. Photo: GENYA SAVILOV / AFP via Getty Images

The Budapest Memorandum was a guarantee of Ukraine’s territorial sovereignty, from the Russian Federation and the United States, in exchange for Ukraine’s voluntary relinquishment of its nuclear weapons stockpile left over from the Soviet Union. However, as the Crimean seizure and Donbas conflict demonstrated, that guarantee meant little in practice. Similar promises, as Vitrenko notes, have been futile: “I personally led the negotiations with Gazprom and signed the gas transit coyntract. In practice, [the Russians] come to negotiations and say: ‘We don’t know what you’re talking about, and who you’ve spoken to without us.’”

Financial commitments

On top of promises to be middle-men in gas transit negotiations, and vague murmurs of sanctions at the sight of Kremlin aggression, Germany agreed to some defined dollar amounts as well. The statement reads that Germany will “establish and administer a Green Fund for Ukraine”, in order to help Ukraine transition to a more energy-efficient and green economy, to the tune of $1 billion. However, the number is aspirational – Germany first donates $175 million to the fund, then “will work toward extending its commitments in the coming budget years.” Whether or not the fund will ever reach the vaunted $1 billion is up in the air, and likely subject to political pressures from all three countries – the U.S., Germany, and Ukraine. The United States in particular makes no financial commitments to this fund, only saying that it, along with Germany, will “…endeavor to promote and support investments…including from third parties such as private-sector entities.”

More direct help comes in the form of a special envoy to be appointed by Germany, with funding secured at $70 million. This envoy will work on much the same goals at the eventual Green Fund, with a focus on supporting Ukraine from transitioning from coal mining, the domain of oligarch Rinat Akhmetov. Germany also states that it will assist Ukraine in strengthening reverse gas flow capabilities – an important tool to counter Russia’s gas maneuvers.

Activists have occupied a pipe on the Eugal line. The project is being built and operated by a subsidiary of BASF and the Russian Gazprom Group. Photo: Stefan Sauer/picture alliance via Getty Images

These maneuvers have been on-going ever since the deal was announced – currently, Gazprom has completely cut off gas transit to Europe, despite a deficit of stored gas on the continent. This, as Dr. Alan Riley, a Senior Fellow at the Institute for Statecraft and an advisor to Naftogaz, notes, is a move by Russia “clearly designed to pressure EU regulators to force through Nord Stream 2, by an implicit threat to withhold gas exports. There will be sufficient Russian gas exports, Gazprom is saying, but only if Nord Stream 2 is cleared, and regardless of EU rules.”

In other words, Russia is already using Nord Stream-2 as a weapon – underutilizing Ukrainian gas transit capability in favor of drumming up demand for its new, Ukraine-bypassing, pipeline. Yet with the ink on the Washington-Berlin deal barely dry, either country pushing the issue and activating the commitments contained within is highly unlikely. Kyiv, along with Warsaw, are still working to stop the pipeline from being used at all, even if it’s constructed, and Kyiv is separately pushing ahead with consultations afforded to it by the E.U. Association Agreement. However, the fate of the pipeline is ultimately in German hands. “Ultimately, it comes down to sacrifice…in order for Europe to say no [to Russian gas], they’re going to have to freeze for a winter. It goes back to the question of ‘How much is Ukraine really worth?’” notes Atlantic Council fellow Terrell Starr.