Before the start of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, architecture researcher Semen Shirochyn spoke specifically for Zaborona about the architectural wealth of Ukraine’s industrial cities, which were stereotypically not perceived as touristic. Today, these cities are at the epicenter of hostilities: in Shostka, the Russians fired at enterprises with a centuries-old history, Zaporizhzhia still suffers from enemy attacks almost every day, and Mariupol was besieged for more than three months, after which the invaders captured it — now the city looks like this. The hero of the new material is occupied Kherson, which today has become one of the critical directions of the Ukrainian counteroffensive.

History and structure

Kherson was founded in 1778, with the name obtained in honor of the ancient city of Chersonesos. In those days, Prince Grigory Potemkin needed a fortress on the way to capture Ochakov, which after the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739, turned into the main base of the Turkish fleet on the northern shores of the Black Sea. Kherson could have originated in another place: the territories of the modern cities of Hola Prystan and Kizomys in the Kherson region were considered. But in the end, the town was founded a little higher up the Dnipro, next to the Oleksandr-Shants fortification. Such an arrangement had advantages precisely from a military point of view.

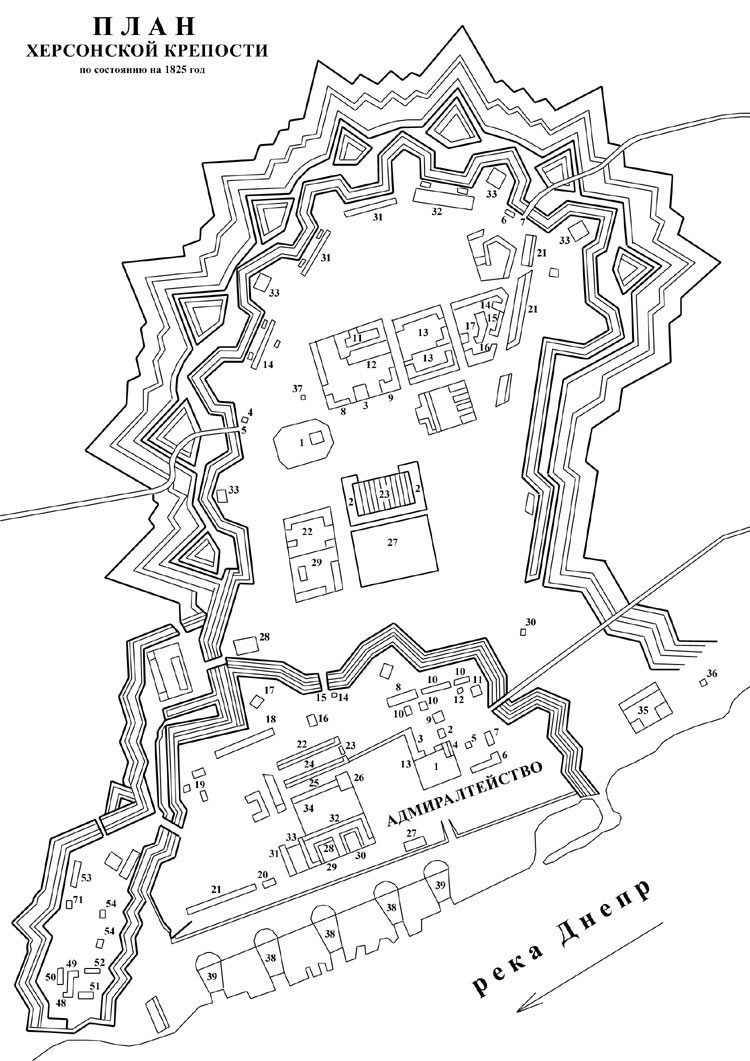

-

Fortification, 1825. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

In addition to fortification, there was also a need for a suitable location for building a shipyard and a riverport. It arose together with the city as the first cargoes for the fortress builders, and the shipyard came here from the upper reaches of the Dnipro. In 1802, Kherson became the district city of the Mykolaiv province, and in 1803 it became the administrative center of the Kherson province, which contributed to the city’s development and the port.

Even then, Kherson became an important center of shipbuilding. The first to appear here was the 66-gun battleship “Slava Kateryna” and the 50-gun frigate with the famous name “Georgiy Pobidonosets,” launched from the docks of the Admiralty Shipyard in 1783. Empress Catherine II and her colleague from Austria, Emperor Joseph II of the Holy Roman Empire, came to observe this in person.

The port and shipbuilding nature of the city had a significant impact on its development and determined future problems, first of all, the city’s isolation from the water. At the beginning of Kherson’s existence, the area along the coast was marshy. In the first half of the 19th century, the swamps were filled in, and the entire coastal line was built with piers. In Soviet times, a single river port was created here — a closed area that cut off the city center from the river.

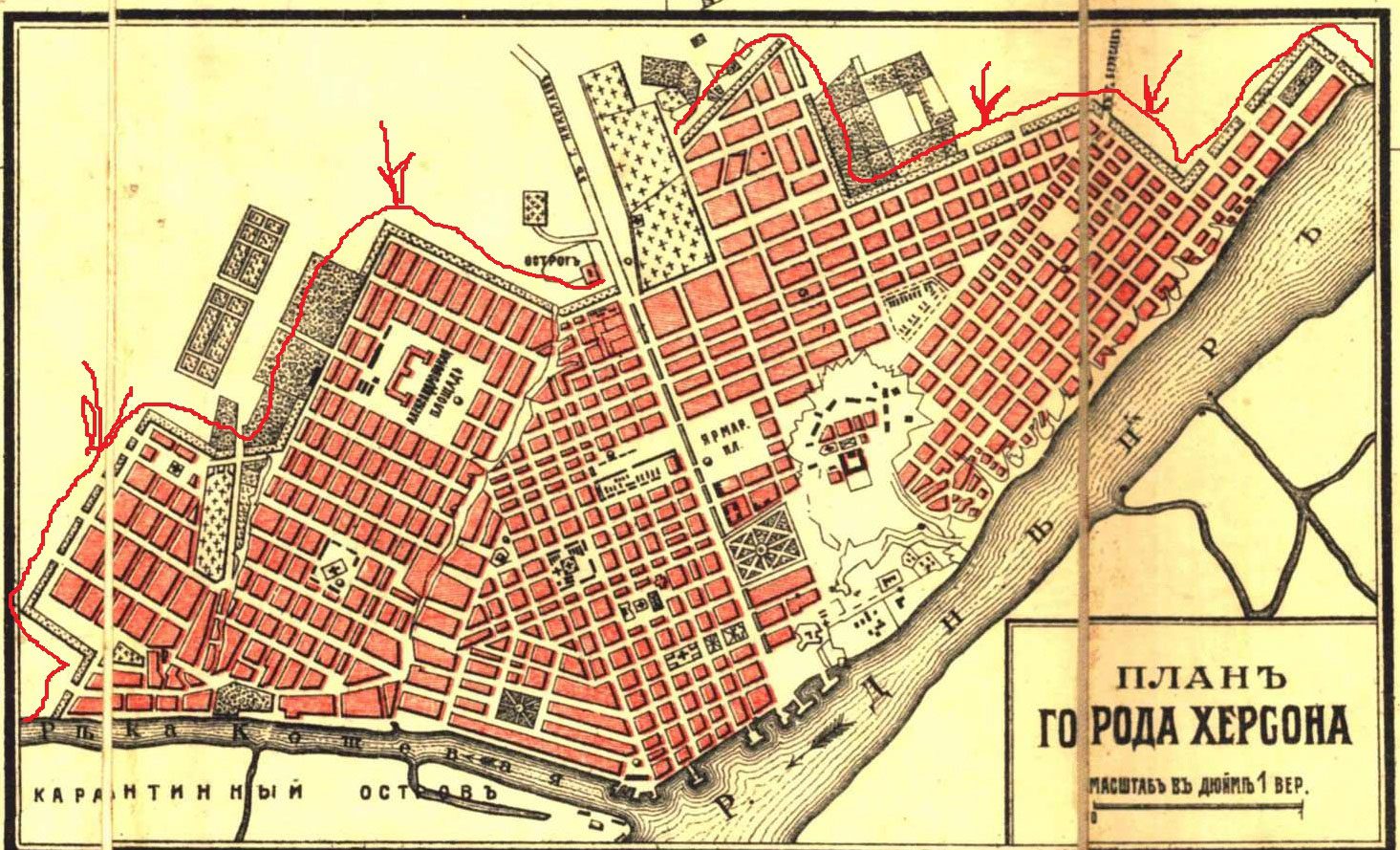

-

Kherson, 1910. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

This problem was apparent: urban planners had proposed moving the port since the 1930s. There were also discussions in the fall of 2021, during the work on the city’s general plan — but at the beginning of 2022, the port chief changed his mind again.

Today, it would be fair to say that Kherson “lost” the Dnipro river. The city embankment is accessible for walking only in three small sections. In addition to the river marine station, you can get to the water only from the Park of Glory (“Arestanka” embankment) and Tutushkina Square (“Fregate” embankment). The latter is the only place in Kherson that offers walks along the Dnipro.

Structurally, the initial center of the city was the fortress. Then, to the west of it, they formed the Kupetsky Forstadt, where most of the interesting buildings of the imperial era are still concentrated. Later, the city grew in different directions, and new residential areas appeared. Some of them were built a considerable distance from the center, as the private development areas remained almost unreconstructed. Due to this, part of the residential areas is separated from the center by a railway.

Fortress

The Oleksandr-Shants fortification, which determined the location of the future Kherson, became the basis of the fortress, which played the most significant urban planning role at the beginning. The ensemble of the Kherson fortress was built at the end of the 18th century — it is a typical example of early classicism architecture, closely related to the previous Baroque period.

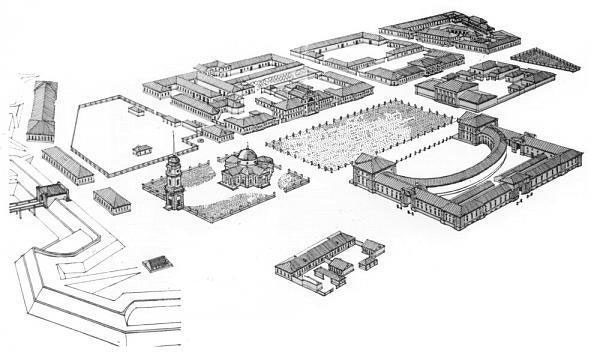

-

Fortress. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

In the center of the Kherson fortress stood the palace of the governor-general of the Novorossiysk region, Prince Grigory Potemkin. Its facade was decorated with rusting, the central risalite completed the pediment, and the third floor had arched loggia.

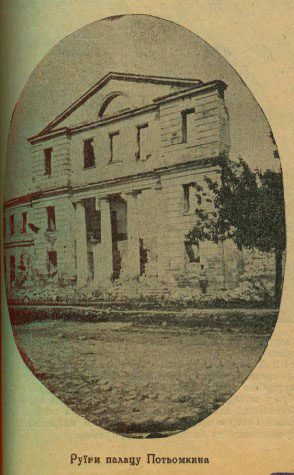

-

Ruins of the palace. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

-

Fortress, 1908. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

After Paul I came to power in the Russian Empire, the main guardhouse, commandant’s office, and Ordonanshaus [building of military-administrative administration] were in the fortress, and the stables and auxiliary buildings were converted into a military hospital. The palace’s architecture also changed: the arched loggia was replaced by three standard windows with a complex profile, the shape of the roof was simplified, and a semicircular skylight was in the gable. In 1911, an officers’ club was in the Potemkin Palace. In the 1920s, the upper floors of the palace were dismantled for firewood, and the lower floors, in turn, gradually collapsed.

-

The Potemkin Palace. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn -

The Potemkin Palace. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

After the Second World War, a park was built on the territory of the fortress, so they decided not to restore the ruins of the palace. However, several buildings remained from the fortress, particularly the Moscow (Northern) and Ochakivska arched gates of the end of the 18th century. A fortress well built in 1785 by the fortification engineer Mykola Korsakov remains from the parade square. Initially, its depth was 80 meters with a shaft diameter of 4 meters. Today, the depth of the well reaches about 30 meters and is lined with Ingulets stone.

-

The Potemkin Palace. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

On the opposite side of the street from the park, the Perekop arsenal, decorated with a monumental colonnade, is preserved — one of the earliest and largest buildings of the fortress. It was built in 1784–1788 according to the project of engineer Ivan Strugovshchikov to store weapons and artillery. The main entrance was decorated with a four-column portico, which after reconstruction in 1812, became a six-column one. A little later, the building was repurposed as a detention facility.

-

Perekopska, 6. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

In 1781–1786, the Cathedral of St. Catherine of Alexandria was built on the territory of the fortress. The light sandstone building has rusticated walls and an entrance of the Tuscan order. In 1800–1806, a bell tower was added to the cathedral, but a few years later, an earthquake occurred in the city, and the building was dismantled. After that, only the belfry’s first tier remained, on which a disproportionate superstructure was already carried out in our time.

-

Bell tower and St. Catherine’s Cathedral. Perekopska, 13. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

-

Bell tower and St. Catherine’s Cathedral. Perekopska, 13. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

Merchant Forstadt

After the capture of Ochakov (1788), the Kherson fortress quickly lost its military significance. In the 19th century, the city’s center became the merchant foretown, located west of the fortress and close to the port. Before the appearance of the railway connection in 1907, the Dnipro river was the most important road to Kherson – land routes were secondary. The view of the city from the water was its main facade. Therefore, tall buildings began to be built near the port: the City Duma, the Art Museum, and the Hotel “Europeyskyi” — the highest buildings of the then mostly one- and two-story city.

-

City Duma, 1908. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn -

City Duma, 1908. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

The art museum built in 1905 (34 Soborna St.) became Kherson’s most prominent building in the imperial era. It was erected for the Kherson City Duma as part of an architectural competition, the winner of which was the famous Odesa architect Adolf Minkus. Local architect Anton Svarik completed the project.

-

Art Museum, Soborna, 34. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

The building has a corner tower, which refers to the town hall towers of European cities. The south facade has a deep gable, a Renaissance pediment, and a stone balustrade on the roof. The house’s facades are made in the style of the Florentine Renaissance: in addition to the rusticated surfaces, there are rusticated columns. The house’s interiors are also designed in the Renaissance spirit, many decorated with stucco. Since 1978, the art museum named after Shovkunenko, an outstanding artist from Kherson, has been operating here.

Next to the art museum is the distinctive building of the local history museum (Soborna, 9). It was built in 1894 according to the project of the architect Vladyslav Dombrovskyi for the District Court. The museum has a complex symmetrical plan with two internal rectangular courtyards. The main facade from the side of Vorontsovska Street is accentuated by a double risalite, decorated with sculptures with semicircular niches and a triangular pediment with two windows at the corners of the facade. At the entrance, there is a broken curvilinear pediment supported by brackets.

-

Museum of Local History, Soborna, 9. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

The city clinical hospital named after Karabelesh (Ushakova, 22) attracts attention. The Empire-style three-story building of 1914 still retains its original appearance. The central risalite is decorated with numerous festoons and two Ionic semi-columns. The side elevations are also decorated with festoons and end with a pediment with a wide arched window at the level of the technical floor.

-

Ushakova, 22. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

The two-story classicist building of the Registry Office, built in 1897 for the public library (Torgova, 24), deserves attention. The main facade of the building is decorated with a four-column portico with a pediment, stylized according to ancient Greece. Old photos show a turret with a dome and a stylized kugel, which have not survived today.

-

Library, 1910. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

-

Library, 1969. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn -

Library. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

There are also good examples of manor buildings in the city. The Kulikovsky estate, also known as the “house with the Atlanteans,” has been preserved at Suvorova Street, 8.

-

Suvorova, 8. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

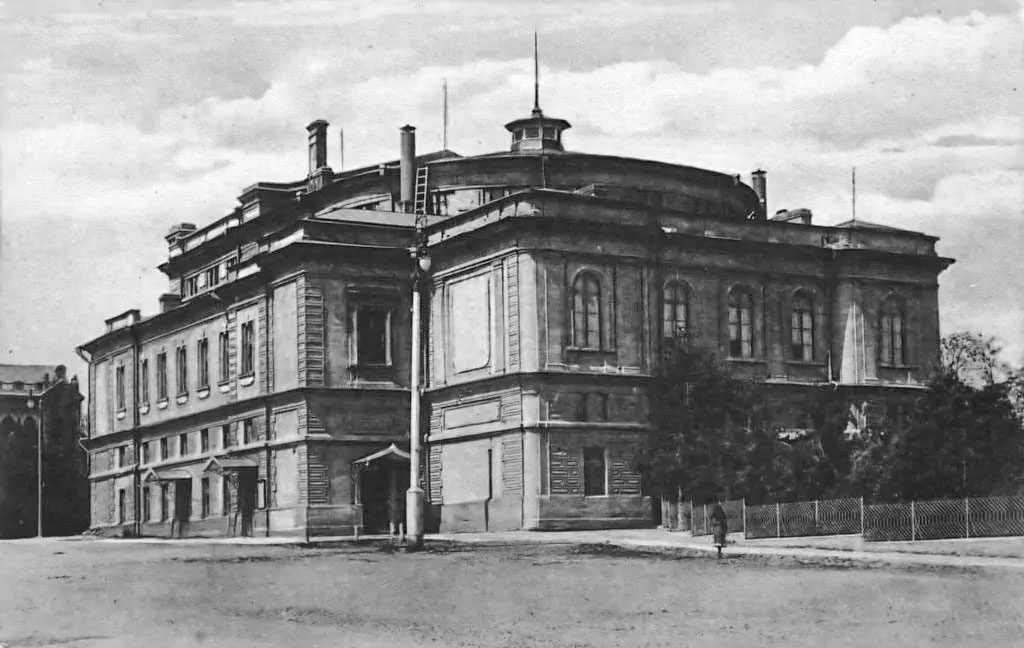

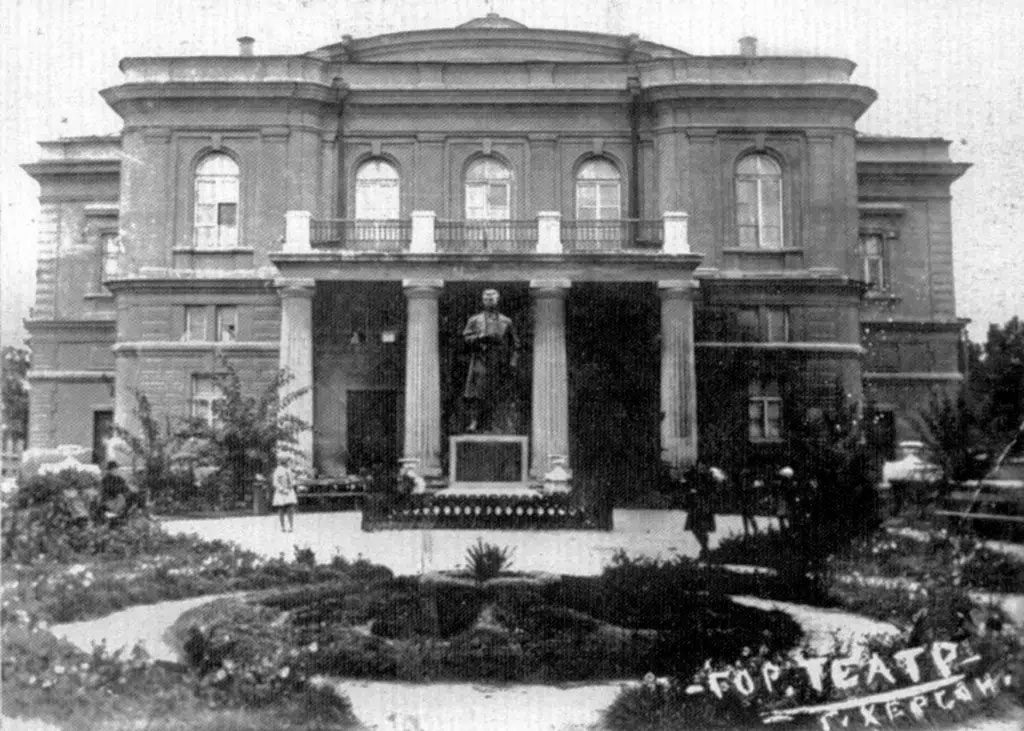

In 1889, a city theater was opened in Kherson, built according to the project of the architect Vladyslav Dombrovsky, who, according to him, took the premises of the Odesa Opera House as a basis. The three-story Renaissance building dominated the space, but it was destroyed in 1944 during the city’s liberation from the Nazis.

-

Theater, 1910 and 1939. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn -

Theater, 1910 and 1939. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

Cinemas also operated in Kherson during the tsarist era. In 1915, in a separate building of the early 20th century at Teatralna Street, 17, local businessman Ishaya Spektr opened the “Empire” cinema, one of the first in the city. It was here in 1930 that the people of Kherson saw a movie with sound for the first time. In the late 1990s, the cinema survived an arson attack, after which it was closed. Now it is deserted and continues to collapse gradually.

-

Teatralna, 17. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

1920–1950s

The Kherson province, formed in 1803, was liquidated in 1922, and before the Kherson region appeared in 1944, the priorities and volumes of construction here were significantly lower than in the regional centers. That is why there is so little architectural heritage of Constructivism in Kherson. On Maria Fortus Street on the western edge of the city (Naftogavan), an attractive building from the late 1920s has been preserved, which combines the inertial architecture of the 1920s and proto-constructivist aesthetics. The symmetrical facade of the building has continuous glazing of stairwells, central and side elevations gables, and vertically elongated windows. Such a combination occurred only at the end of the 1920s and is quite rare since not many were built then.

-

Maria Fortus Street, 2011. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

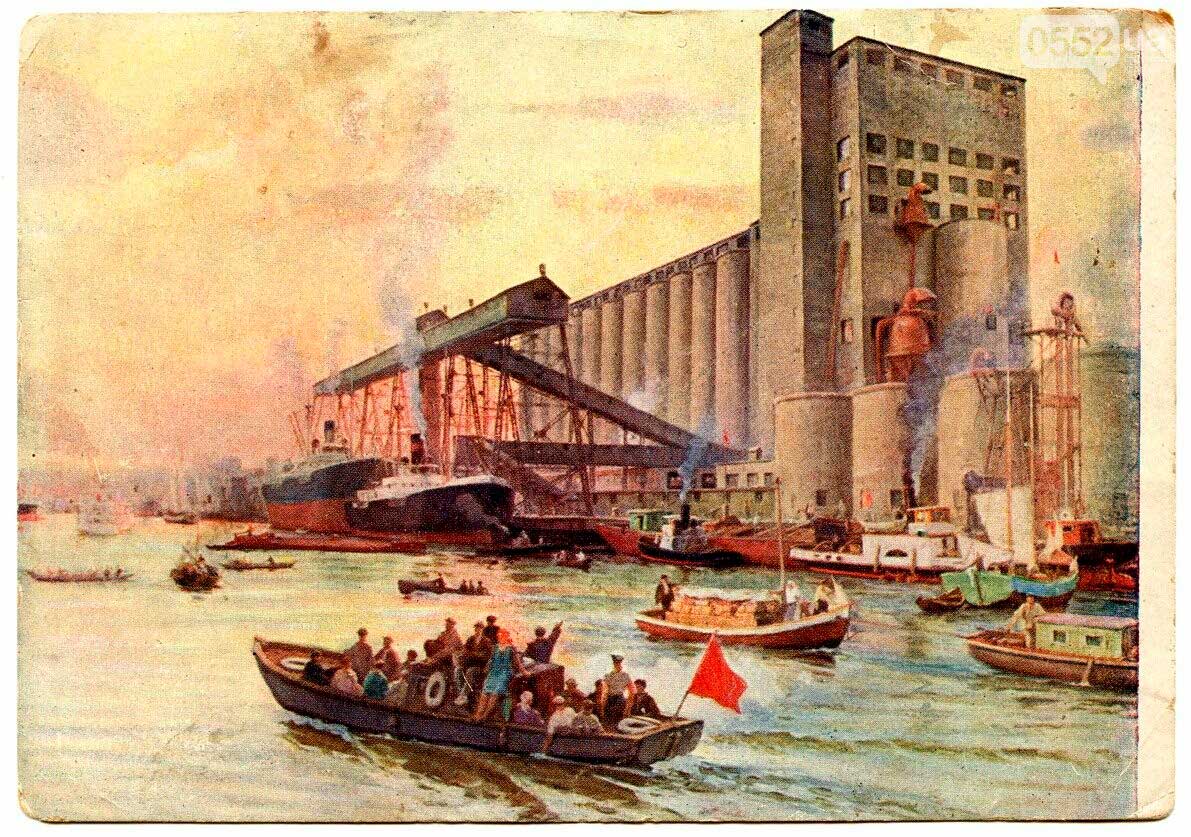

The era of constructivism left Kherson an exciting port elevator complex. It was built in 1930–1932 according to the project of the Soviet branch of the American project firm Albert Kahn Associates (Detroit), which was named “Derzhproektbud.” The organization was headed by Maurice Kahn, the brother of the company’s founder, who came to the USSR with 25 engineers. The 66-meter central elevator tower makes it the tallest building in the city. In addition to the direct industrial architecture, a two-section apartment building of the administration was built in the elevator complex, the facade of which is decorated with the continuous glazing of the stairwell characteristic of constructivism.

-

Port elevator. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

In 1944, with the formation of the oblast, Kherson again became an administrative center, which increased its hierarchical importance and priority in financing construction. Local project organizations (“Khersonproekt,” “Khersonkommunproekt”) appeared, where local architects, engineers, and designers developed projects for the construction and restoration of damaged buildings. The authors had to limit themselves to local building materials and avoid scarce metal and wood. Therefore, a significant part of the houses in the 1940s and 1950s were built from local stone — rubble and shell.

Many construction projects of that era were damaged during the Second World War. They were restored using the original foundations and walls and, in some cases — with the preservation of the surviving facade. Some of them were even nominated for competitions.

So, for example, the dormitory of the cadets of the Kherson Maritime School was restored in 1949 according to the project of architect Georgy Skolozubov and engineer Vasyl Peshkov. The facade of the building was in excellent condition, so the authors were instructed to preserve not only the volumetric but also the compositional solution. The end walls of the building, which were not finished before the war, were decorated in the same spirit as the facade. At the same time, the internal layout of the dormitory was changed.

-

Kherson Maritime School. Photo: Olga Nesterenko / Wikimedia

Another restored building was the Watermen’s Polyclinic at Ushakova Avenue, 19A. It was restored using the preserved foundation and walls according to the project of architect Ivan Klushkin and engineer Pavlo Gatsenko. The building combines spatial and spatial solutions typical of the 1930s and the windows’ width with the facade’s post-war decorativeness.

-

Ushakova, 19A, 1953. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

The development of the 1950s was aimed at creating coordinated architectural ensembles that appeared both in new quarters and among existing buildings. Ushakova Avenue, which connects the embankment with the railway station, is the most crucial thoroughfare in the architectural hierarchy of the city. Outstanding architectural buildings of different eras are concentrated here. A unique role is played by the intersection of the avenue with Suvorova Street, an essential city promenade.

Shevchenko Park’s entrance is on one side of the intersection, equipped with a parade colonnade. Another corner of the intersection is visually dominant — a 4–5-story building at Ushakova Avenue, 8. It was built in 1950 according to the project of architects Hryhoriy Trudler and Yudifa Zolotarevska for employees of the shipyard. The 4-story building has an elevated corner 5-story part topped by a rotunda tower.

-

Ushakova, 8, 1950. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

Another interesting landmark is the 3-story residential building at 32-34 Suvorova Street, built in 1949-1950 for Shipbuilding Plant No. 873. The architect Yevhen Aleksandrov was the author of the project. The building occupies the corner part of the quarter and is included in the existing continuous building. The central compositional axis of the building is located on the side of Suvorova Street, which emphasizes the risalite with the pediment and the architectural decoration of the entrance. Its corner axis with a tower in the form of a light rotunda balances it. Initially, the tower was crowned with a decorative spire and obelisks. The spire was later lost. The facade of the house is plastered. The slats’ relief, the corner parts’ rusting, and the cornice give intense light and shadow on the smooth surface of the wall.

-

Suvorova, 32-34, 1950. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

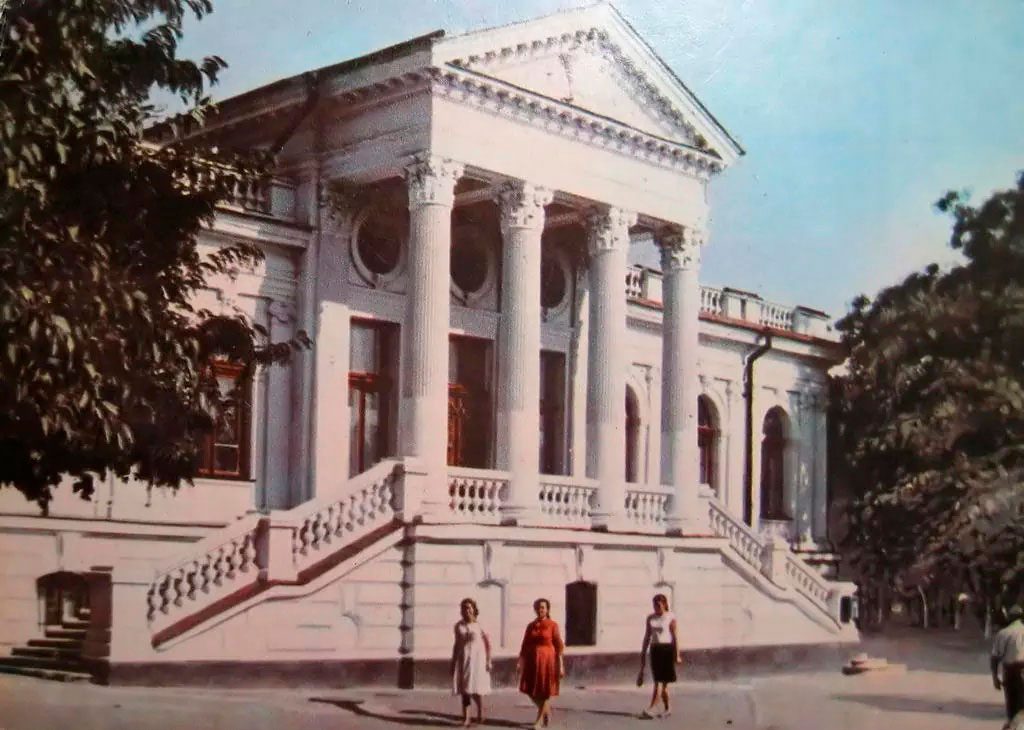

In the post-war period, the lost infrastructure was also rebuilt. In 1962, instead of the building of the drama theater destroyed in 1944, the regional academic music and drama theater was named after Mykola Kulish. The project was developed by architects Oleg Malyshenko and Oleksandra Krylova from Kyiv Dipromist. In addition to Kherson, it was also used in Poltava, Mariupol, Rivne, and Chernihiv. Despite the fight against excesses, which began as early as 1955, the facade of the Kherson theater is similar to the Poltava prototype. Still, the corner towers are devoid of capitals, the portico columns look heavier, and the pediment is empty of any sculptures.

-

Theater named after Kulish. Photo: Semen Shirochyn -

Theater named after Kulish, 1990. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

During the reconstruction of cities in the 1950s, special attention was paid to ensembles of central squares. Kherson was not flattered in this regard: the ensemble on Freedom Square managed to be partially built, and due to the struggle with excesses, most buildings on the square were Khrushchevkas. The most prominent in the ensemble are the city council building (Freedom Square, 1), the administrative building (Ushakova, 47), and the Ukraina cinema (Ushakova, 45).

The four-story building of the city council, which occupies a dominant position in the ensemble, has two lateral risalites, and the central part of the facade is decorated with ten pilasters. In front of the entrance to the building are monumental lanterns with national floral ornaments, made in the early 1950s. The same design of lanterns is present in the most important areas of some other cities: near the Mykolaiv City Council, in Mariinsky Park in Kyiv, near building No. 25 on Khreshchatyk, etc. Kherson lanterns differ from Kyiv lanterns in the presence of granite supports, which makes them even more valuable.

-

City Council building. Freedom Square, 1. Photo: Semen Shirochyn -

Administrative building, Ushakova, 47. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

The most interesting in the ensemble is the history of the “Ukraine” cinema opposite the city council. It was built in the 1950s in a style characteristic of the time — the main facade had a portico of four paired columns. In this form, the cinema existed until the mid-1960s, after which the pediment was replaced by a flat entablature along the height of the building. The columns took on the appearance of rectangular pillars, which simplified the architecture of the building.

-

Cinema “Ukraine”. Ushakova, 45. Photo: Semen Shirochyn -

Cinema “Ukraine”. Ushakova, 45. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

-

Cinema “Ukraine”. Ushakova, 45. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

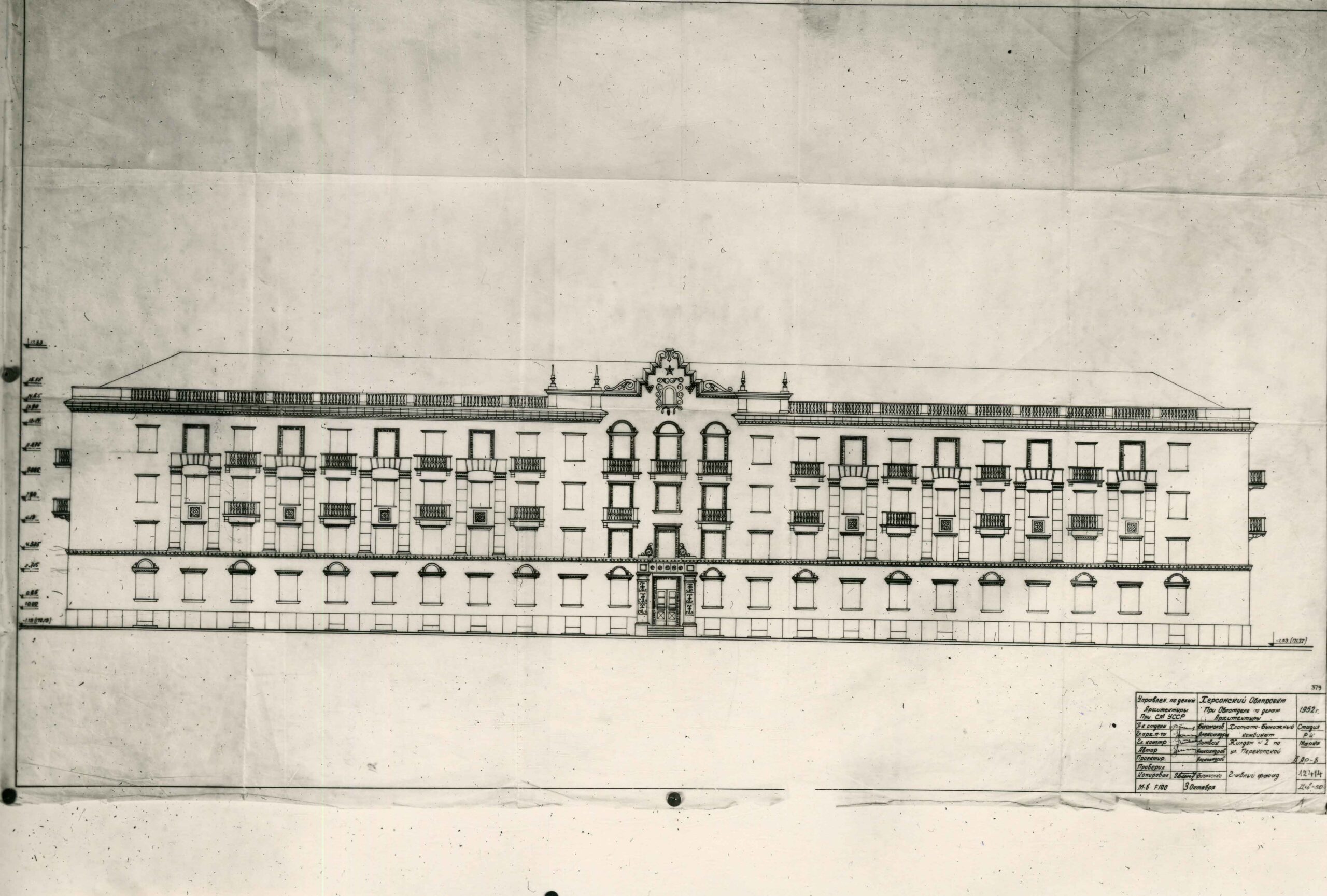

In 2012, they decided to reconstruct the cinema, for which it was largely demolished. As a result, four paired columns (with different shapes of capitals) were returned to the building, and a disproportionate turret with a spire was built over the central part of the facade. The overall volume of the building has increased — it has glass facades at the edges, which do not fit well with the original classicist style of the building. In addition to the central part of the city, ensembles were also built near key enterprises, particularly near the Cotton and Paper Combine on Perekopska Street. In 1952–1954, at 153 Perekopska Street, a four-story building with 48 apartments was built according to the project of architect Yevhen Aleksandrov and designer S. Litvak. The trend of the mid-1950s can already be seen here – instead of plastering, the facade was lined with silicate bricks, and the inter-floor ceilings were made of precast reinforced concrete. Reinforced concrete is also decorative materials — cornices, moldings, brackets, and lintels.

-

Perekopska, 153. Photo provided by Semen Shirochyn -

Perekopska project, 153. Photo courtesy of Semyon Shirochyn

During the Russian-Ukrainian war, the occupiers captured Kherson without a fight. Still, the shelling of the occupation administration led to the destruction of the architectural heritage, the extent of which will be understood only after the liberation of the city.

On September 28, 2022, an elegant three-story building with attics designed by Ludmila Shkaruba was destroyed due to shelling on Universitetska Street. It is also known about the destruction caused by the blows to the city council’s building.

The age of modernism

In the 1960s–1980s, the city grew rapidly. New residential areas were built mainly on vacant lots on the city’s outskirts due to the problem of long distances. Between the center and new high-rise residential areas, there are sizable private development areas with a network of narrow streets. The development of the city and transport connections were hindered by the railway, the port branch, and the beam, through which only one bridge passes today. The largest among the new districts was the Cotton and Paper Combine residential area in the city’s eastern part. In 2015, about 42,000 residents lived here. The buildings here are primarily typical five-story Khrushchev buildings.

-

Cotton and Paper Combine, 1976. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

In the western part of the city, during the 1930s–1950s, they began to build a housing estate. Its inhabitants at that time were mainly workers of two local industrial giants — cardan shaft and semiconductor factories. The buildings here are mixed 5-story and 9-story, and many panel houses have been built.

-

Residential settlement, 1980. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

But the city continued to grow. Other residential areas were built behind the railway. Thus, in the 1970s, the Western housing estate (also known as Shumensky) appeared. In the northern part of the city, also behind the railway, Tavriysk micro-districts — the first, second, third, and fourth — whose development borders on the private sector and wastelands have emerged. The Tavriyskyi-2 micro district is also known for the most extended house in Kherson, 841 meters in length and 1,535 meters in total. The house has five different addresses and is the third longest in Ukraine after Lutsk and Kyiv.

-

Shumensky housing estate, 1980. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

The latest in Kherson was constructing the Korabel complex, which consists of two micro-districts. It is unique, particularly in its location — it is the only residential complex built on Quarantine Island. There are mainly 9-10-story buildings from the 1980s-1990s. In addition to mass serial housing, the age of modernism left the city with several iconic and architecturally valuable buildings. One of the hallmarks of the town is the “Yuvileyny” movie concert hall, built in 1970 based on the reused project of the Kharkiv movie concert hall “Ukraine.” The hall has a recognizable roof geometry and looks spectacular on the square opposite the fortress. The name “Yuvileyny” is associated with the centenary of Lenin’s birthday, which fell in 1970, the year the hall’s construction was completed. Today, there are two movie theaters here, and the larger one has a capacity of 1,500 people.

-

Cinema-concert hall “Yuvileyny”, 1978. Photo courtesy of Semyon Shirochyn

Another distinctive building of the time was the river-sea station, built on the site of a neoclassical building with an elegant turret and an arcade on the waterside. The surrounding square was built in a single ensemble with the old station. The new building combines a river-sea station, a restaurant, and the Meridian hotel. The silhouette of the building resembles a ship, and the number of floors gradually increases closer to the western part. The method of stylizing a modernist building under a ship was used in another landmark of the city — the Hotel “Fregate” on Ushakova Avenue, 2. The project of the 11-story hotel in 1979 was developed by architects Marchenko and Mykhaylenko and engineer Fertman. But the construction of the hotel was completed only in 1989. The ship-like effect of the building provides an elongated silhouette with a vertical volume of elevators and interesting superstructures similar to the liner’s decks. The rooms resemble the structure of the cabins, and the round windows-portholes of the technical floors and the end wall complete it all.

-

Hotel “Fregate”, 1989. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

The hotel was built with two restaurants, bars, a hairdresser, a sauna, and a garage. From the outside, the building is faced with granite, tuff, Inkerman stone, aluminum profile, and decorative plastering. The floors in the interior are granite, marble slabs, artistic parquet, ceramic tiles, mosaic, and linoleum. In 1990, the hotel was nominated for the best buildings of the year competition.