“Tomorrow I Might Be Killed by a Missile. I Don’t Want to Hide.” Two Stories of LGBT Soldiers Defending Ukraine

After February 24, a separate LGBT military platoon appeared in the Armed Forces of Ukraine. However, not all representatives of the community who are currently defending the freedom and sovereignty of the country serve in it. It is not known exactly how many queer people have put on military uniforms because many are afraid to come out and run into condemnation or aggression. Zaborona talked to a gay and a lesbian who dared to tell their brothers and sisters about themselves – we present their stories almost without editing.

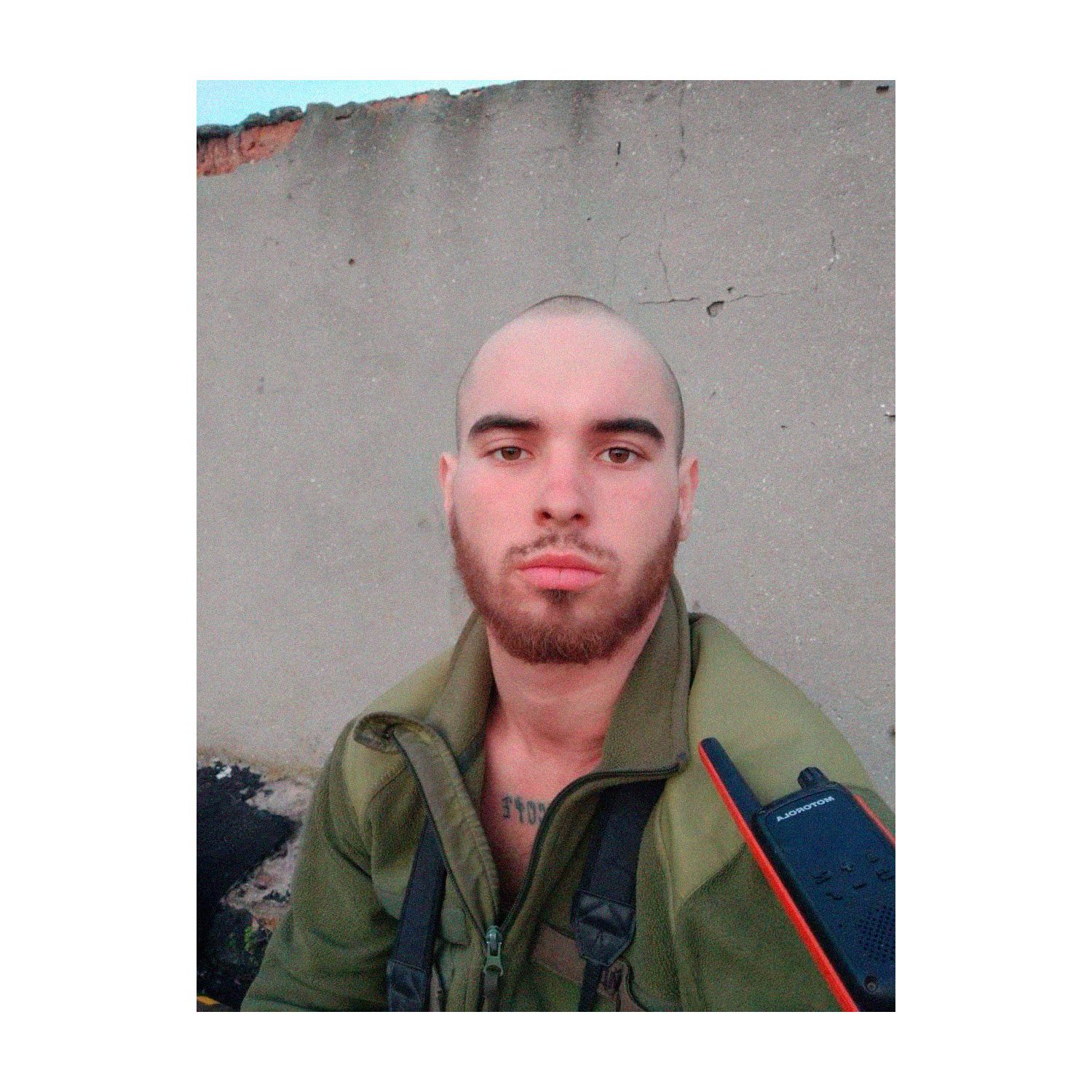

Pavlo Lagoyda, 20 years old, anti-aircraft gunner in the Armed Forces

Before the full-scale invasion, I was an LGBT activist. In fact, I still consider myself like that. As of February 24, I was doing my conscription service, two months remained until the end of it. I remember, the last weeks before that, I came across a video on social networks showing Putin pulling troops to the borders with Ukraine. I understood that something was wrong, and I discussed it with the guys in the unit.

-

Photo courtesy of Pavlo

On February 22, we were sent to deployment. Everyone understood that something was going to happen, so we started to prepare. We hoped that this command was just for the check the combat readiness. It turned out that we were going to war. At first, we were deployed in the first position – it was a forest. The first days we just sat, servicing the equipment that was brought to us. Then we dug trenches.

On February 24, we woke up to the sounds of explosions. We immediately got into the trenches. Some of the guys began to pray. I was also very worried. Didn’t know what was going on. An enemy fighter flew over us. The command ordered to take positions. We began to move all our equipment and artillery to other positions. Then we went to the field and started working.

From the first days, I kept in touch with my relatives. They were in a panic – they were very afraid because they did not understand what to expect next and where the Russian troops could reach. I called my mother in Ivano-Frankivsk and told her to pack her things, take my grandmother, and all her relatives and quickly go to my sister in Germany. I was very worried for them, so I decided to do everything for them to go abroad.

But my mother is a stubborn woman. She said that until she sees me at the door of the house, she will not go anywhere. I cried, my imagination painted bad pictures. Begged her to go – she said she would be here until her last breath. Thanks to fate, it’s really more or less calm in my hometown now, so I calmed down a little.

I often think about death – it has become an inseparable part of life. I wake up, I go to sleep – I thank God that I am alive and well, that I can still tell my story.

When it all started, I didn’t think about it: I had a task – I carried it out. We were told what to do, we loaded the shells and fired. There was no time to think that I might die.

Relations in the battalion developed normally: I made friends with someone and communicated with others in a friendly way. There was one guy, we communicated very well. He was the first to learn about my orientation. It was last summer – I was then a low-ranking soldier, and he had the higher rank.

We became friends. Once we worked in the field together. I asked how he felt about gays. He said, “Not very well. A man should love a woman, a woman should love a man. Nothing else is given.” And then I thought that I had to tell everything either now or never. It was important for me that he knew this so that I no longer had any boundaries in communication. I confessed to him. Over time, he accepted it. Now, this friend is no longer alive – he died in the war.

My relations with other colleagues were also good. You can’t get along with everyone, because everyone has their principles, and vision of the world. I understood this, so I never imposed my orientation on anyone. I was myself as much as possible. I had this position: if someone doesn’t like it, I don’t ask, I don’t force them to accept it.

No one behaved aggressively with me, but everyone discussed it behind my back. This is happening even now. They communicate well with me, but not everyone dares to tell me about their homophobic position. I always say that I am ready to answer questions and listen to criticism. We can somehow agree, and find a compromise.

When the company learned the truth, there were different reactions. I will not say that everyone accepted me immediately. It was different: someone didn’t care, someone couldn’t imagine how it was possible for a man to love a man. When I saw that a person was going to be aggressive, I just turned around and left, because it is not constructive to argue here. When a person calmed down, everything was fine.

My commander knows I’m gay, we don’t talk about it. They even call me a bunny. He respected me, for which I sincerely thank him.

-

Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

It seems to me that during the war people became more tolerant. I think that after the war there will be no homophobia. I read the comments in the LGBT military group – there was almost no homophobia. People wrote words of support and thanked for the service.

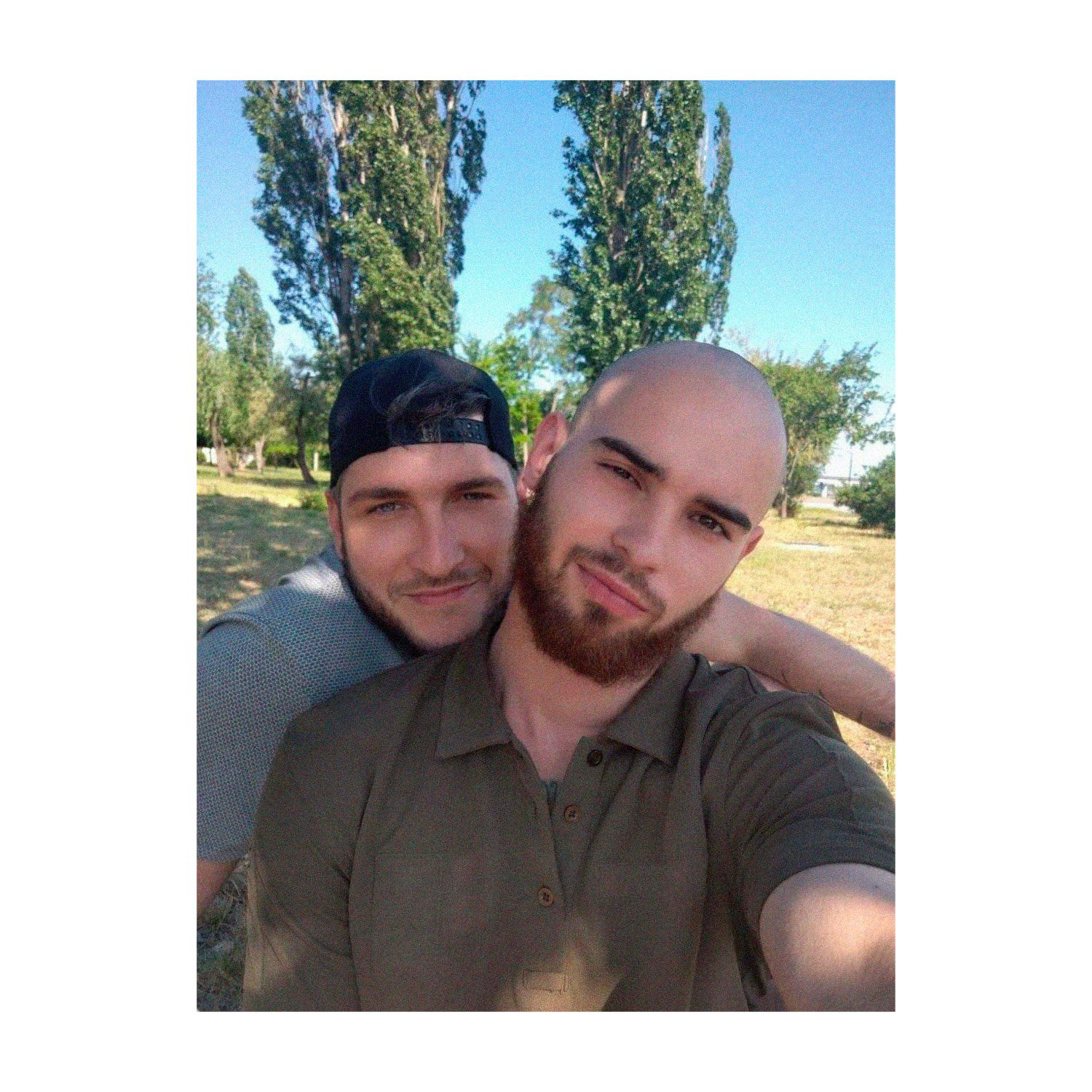

In 2014, my partner served in the ATO area — he was a combat medic. He knows well what war and death are. He knows that I am worried here, how scared I am sometimes. He is currently working in Kyiv, but we call each other every day. He supports me and says: “Pasha, you will be strong. Everything will be fine. We will meet soon.”

-

Photo courtesy of Pavlo

I want everyone to know that different people are ready to defend our Ukraine, our sovereignty, and our territorial integrity. People of different nationalities, religions, orientations, and ages are currently at the front. Ukrainians should understand that we stand for their peace and sleep at night and in the morning without sounds of explosions. It doesn’t matter who you are, because now your main function is to kill the enemy and prevent him from [advancing] further.

Alina Shevchenko, 29 years old, mechanized battalion headquarters officer

In 2014, when the war started, I was still a student. The following year, I graduated from the university, was called during mobilization – it was the sixth wave. Then I signed the contract.

Joining the army in the years when the Russian-Ukrainian war had already begun was not a very conscious choice. I graduated from the military department, besides, my stepfather is a military man. I saw myself in the army. Only later, after a year or two, when I started working in the ATO area, in rotation, I realized what kind of war is this, what is this war for. I understood that I was in my place.

-

Photo courtesy of Alina

When I was still serving in the Military Commissariat, it was a little scary because I was surrounded by people who were a little afraid of war. In fact, war is always scary, on any scale.

I was then among such people who did not feel confident. It was such atmospheric fear. And when I got to the place where I serve, in my combat brigade, it became easier. Everyone there has been defending Ukraine since 2014, and this spirit was passed on to me. I understood that you can go to battle with these people.

Now I am engaged in full-time work related to staff accounting: people who have expressed a desire to defend the country are brought to us at the military commissariat, and we work on their data. I collect all the statistics, reports, and analytics.

On the eve of the full-scale invasion, I took a vacation, which ended exactly on February 23. I had to be at work the next day. I was going to attend the line-up of the commanders in the morning. Our guys then left to meet the enemy – I did not know about it. I heard that there was some kind of tense atmosphere, but I thought that the Russians, as usual, would rattle those weapons somewhere on the borders and go away. I was preparing for another rotation – in Luhansk or Donetsk region, somewhere there.

It so happened that on February 24, I slept during the start of the invasion. My stepsister woke me up. He called and said: “Alina, what to do?”. I woke up, and looked at the clock – it was five in the morning. “Alina, the war has begun.” I said: “What war? What are you talking about?”. I didn’t hear anything at all, I was asleep. She heard explosions: our warehouses were exploding, and aviation was working.

-

Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

I was not ready: everyone was preparing for it, and I had just returned from a vacation in Georgia – I was going to my girlfriend, everything was just starting for us then, it was very romantic. Those damn Russians ruined all my plans.

Within an hour I was already in the military unit. We all got together and started recruiting personnel. People stood at 7-8 in the morning in front of the military unit and were ready for mobilization. Thus a full-scale war began for me.

It was scary and disturbing. I performed all work in the background mode. I understood that the threat is approaching, that fighter jets and shells are flying over us – you hear it all, hide in the basement, recruit people at the same time, and draw up documents for them.

I don’t have any days off right now. Maybe I shouldn’t say that, but during the eight years of war in Donbas, it was easier because I could plan something. You don’t have any plans now because you don’t know what tomorrow will bring. You just have to somehow not lose yourself and not fall into despair.

Mostly people like to control their life and like to plan. Now such a right has been taken away not only from the military but also from civilians. It is very difficult, very exhausting, but I try and advise all my brothers and sisters that if they feel something like this, they better direct it into anger, rage, or something else. Because when you get desperate, you just give up. You can’t do anything out of desperation, and anger and rage are the driving force.

It so happened that I have a mostly female team. Our manager is a man, there are a couple of other men, and mostly all clerks are women. The team learned about my orientation gradually. I won’t say that I somehow hid it, they just don’t ask – I don’t say. Somehow it turned out that this topic came up with one or another [colleague] during communication. I used to say something like: “I’m going on a date with a girl today” and watch the reaction.

Most of the people on the team found out I was a lesbian when I was going through an emotional breakup with my ex-partner. I was sick, and at work, they asked what happened. We have very warm relations in the team, everyone is family. So I shared it somehow. There was practically no reaction: a fool will not notice, and a smart person will not say anything. The management then supported me. I needed some rest, so I asked for a business trip – the boss agreed.

-

Photo courtesy of Alina

Probably, colleagues could whisper among themselves, think something about it. But because of that, they didn’t put a spoke in my wheel, they didn’t insult me. In my opinion, girls in the army are very prejudiced. No matter how hard it is, patriarchy still reigns in the army, no matter how you fight against it. I have hope that this war is moving many things now, including the LGBT issue.

There is still a stereotype among people that “well, girls are normal, girls are aesthetic, being lesbian or bisexual is normal. And if the man is gay, then God forbid.” Not all are like that, but it happens. You sit to yourself and think, why are you so triggered by the fact that a man can be gay, for example, bisexual, or transgender – it doesn’t matter. This is probably some internal problem of this particular person who reacts in this way.

At the beginning of the war, my girlfriend was with her family in Kharkiv. Their house is located on Saltivka, where shelling occurs several times a day. She stayed there until April. I was very worried about her. Even more than for myself. It became much easier for me when she moved to Ivano-Frankivsk with her parents and grandparents.

We communicate with her every day. Distance affects relationships a lot. In general, everything has only just begun. It is very difficult when you have not yet had time to get to know each other. You expected that you would start such a romantic courtship, but then the war began – everything changed very quickly. I immediately said that I love her. She said she loves me too. War makes you more aware of feelings.

This is the person with whom you can discuss Russians. For me, this is a very resourceful thing. They are terrible, cruel, but their stupidity is simply off the scale. It is a sin not to laugh, especially in such times. Together, we dream that the entire Russian people will die.

My girlfriend and I often discuss that after the war there may be a flourishing of far-right organizations. They will take away our rights, manipulating the fact that they protected us in the war. Although now everyone is protecting others – some work as a volunteer, some as a medic, some as a soldier, and some on the information front. And you want to say that there is no one from the LGBT community among these people? The LGBT community is, first of all, about human rights. We defend all the rights we can. First of all, their own, but also human rights in general.

We were born this way and we struggle to be who we are. It is so difficult in the stable world, where there are already canonical rules. You’re just trying to push the boundaries, and show people that there’s something different.

I can just be killed by a missile tomorrow. I don’t want to be afraid to speak, I don’t want to hide. I know a lot of people who hide their orientation – it’s incredibly difficult.