Ukraine Stops Russian Gas Transit to Europe: Russia Threatens with Consequences, but There Will Definitely Be No Catastrophe

The five-year agreement on Russian gas transit through Ukraine to Europe expires on December 31, 2024. And Kyiv has firmly stated its intention not to continue cooperation with Gazprom. For decades, the Ukrainian gas transportation system (GTS) was a key artery for supplying blue fuel to the European Union, remaining critically important even after Russia launched alternative routes.

The cessation of transit will inevitably affect the European energy market, given that some countries still partially depend on Russian gas. This could provoke fluctuations in energy prices and have economic consequences for both Europe and Ukraine.

However, experts do not forecast catastrophic scenarios for the population during the heating season. Instead, Russia may lose significant financial revenues previously directed to support military operations. About the potential consequences of stopping transit through Ukraine and the impact of this decision on the region’s energy security — in the article by Zaborona’s editors Svitlana Hudkova, Yevheniia Hedrovych.

“Ship or Pay” Instead of “Take or Pay”

The first logical question: why didn’t Ukraine terminate the contract back in February 2022, after the full-scale invasion? It’s because Kyiv had to fulfill its contractual obligations to European partners.

“The money Naftogaz receives from Gazprom doesn’t cover our expenses for organizing this transit, as Gazprom hasn’t been paying the full price almost since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. And our cash flow for this operation is constantly negative,” explained Oleksiy Chernyshov, CEO of Naftogaz Group.

Back in 2019, before signing the latest contract, according to calculations by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Gazprom was just slightly short of being able to manage without transit through Ukraine even without Nord Stream 2. The monopolist would have covered this capacity deficit through gas storage facilities in Europe and LNG supplies from the Yamal terminal. Ronald Reagan, by the way, opposed the construction of the Yamal pipeline in the 1980s, concerned about the leverage it would give the USSR over Europe. His fears were prescient.

However, after lengthy trilateral negotiations, Ukraine, Russia, and the European Union signed a contract on December 30, 2019:

- for five years with the possibility of extension for another 10 years under similar conditions;

- minimum guaranteed transit volumes — 65 billion cubic meters of gas for the first year and 40 billion cubic meters for the next four years. Actual volumes could be higher.

“A transit contract based on the ‘ship or pay’ principle for five years is an unprecedented event. This is the first time in Ukraine’s history that Gazprom has signed a transit contract under the European ‘ship or pay’ principle,” commented then-executive director of Naftogaz Ukraine Yuriy Vitrenko. “Until now, only gas purchases from Gazprom were covered by a similar but disadvantageous for Ukraine and advantageous for Russia ‘take or pay’ principle.”

In other words, the “ship or pay” principle obligates the Russian supplier to pay for the specified transit volumes regardless of actual volumes. Under the “take or pay” principle, Ukraine had to pay regardless of whether it consumed the gas or not.

Ukrainian GTS is Ready for Transit Stop

The 2019 contract also provided for an unbundling procedure, that is, the process of legal and operational separation of the gas transportation function from Naftogaz. Now, LLC “Gas TSO of Ukraine” handles the technical operation of the GTS.

Russia has been waging an open war in Ukraine since 2014, so signing the last contract gave “Gas TSO of Ukraine” time to prepare for the procedure of refusing Russian services. Additionally, Moscow’s manual stops of transit through Ukraine in 2006 and 2009 allowed certain algorithms to be worked out. According to these, the gas transportation system will be reoriented to meet Ukrainians’ primary needs.

“Without transit, the GTS can switch to reverse operation mode and transport gas from underground storage facilities, which are mostly located in Western Ukraine, to the East. So there won’t be problems with fuel supply to all regions. However, since this is an off-design mode, there may be difficulties with pressure reduction in the system. To avoid this, pressure needs to be maintained through greater use of gas compressor units and increased gas volume in underground storage,” explains Volodymyr Omelchenko, Director of Energy Programs at the Razumkov Centre, in a comment to Zaborona.

Heating Will Be Available in Ukraine, but Gas Prices Will Increase

The transit stop will not affect the heating season in Ukraine in 2024-2025. As of mid-October, 12.2 billion cubic meters (Bcm) of gas have been accumulated in gas storage facilities. This is because, during the previous heating season, 8.5 Bcm were withdrawn from underground storage facilities (USF), of which 6.7 Bcm were used.

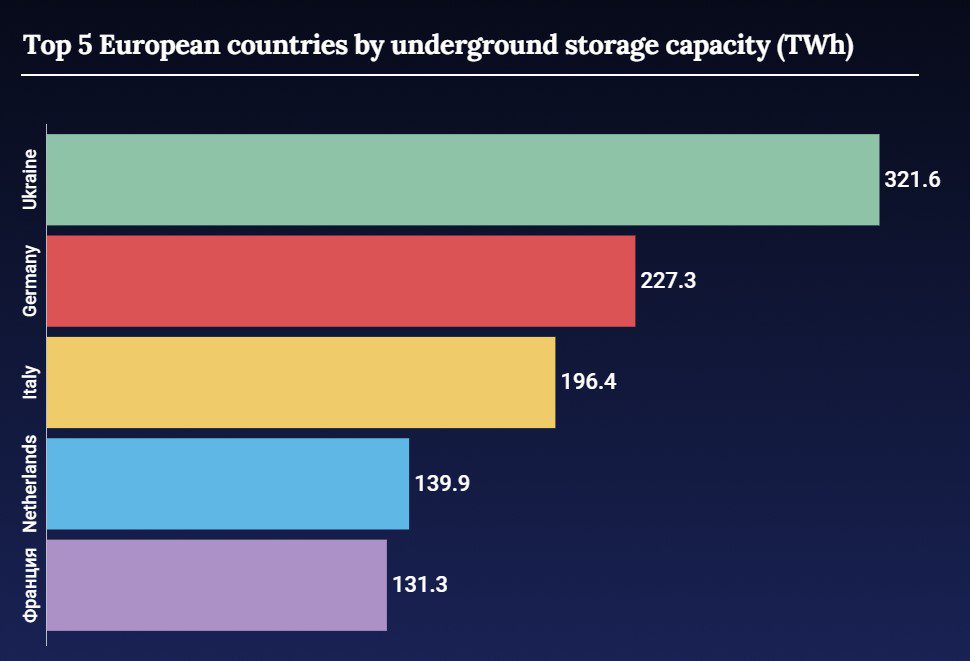

Ukraine manages USF with a total capacity of over 30 billion cubic meters, which is the third-highest indicator in the world, and the Bilche-Volytsko-Uherske storage facility is the largest in Europe. 80% of capacity is located on the western border. The convenience of logistics processes makes natural gas storage profitable for both Ukrainian companies working with cross-border transportation and foreign traders.

Therefore, the gas transportation system will deliver gas to consumers even without transit. The only problem that may arise is Russian missile attacks on gas transportation infrastructure.

But even here, Ukrainian authorities already have a work plan for all emergency cases, assures Andriy Zakrevsky, Chairman of the Board of the Oil and Gas Association of Ukraine.

“Even in case of a massive missile attack, if everything goes down, the authorities have defined work plans to ensure Ukrainians have heat and light in winter. I am one of the members of the group at the National Security and Defense Council that developed this plan, and I can assure that we are ready for any development of events,” the expert tells Zaborona.

Why is it somewhat easier with gas infrastructure than with energy infrastructure? First, the equipment of gas storage facilities and gas compressor stations is not as unique and expensive as, for example, a 750 kV transformer. Second, with zero transit, 80% of the GTS become donors for 20%. “Of course, it won’t be easy, but most consumers in Ukraine won’t even notice any disruptions. Although this will require a lot of work,” Zakrevsky reassures.

However, consumers may feel the consequences in their wallets. Russia paid for transit, and under the current contract, Ukraine was supposed to receive about $7 billion in revenue. Part of these funds were distributed for gas transportation infrastructure maintenance. So in case of non-renewal of the contract, financing will be placed on consumers, believes Volodymyr Omelchenko.

“Of course, financial problems will primarily affect Naftogaz, as the company that concluded the contract. The Gas TSO received its share as the operating company. To compensate for these losses, it will probably be necessary to increase the gas tariff for the population,” says the expert.

Ukraine’s Reliability as a Transit Country

It’s important to note here that for a long time, gas tariffs in Ukraine were lower than market rates. And this is one of the reasons for the unprofitability of the profile state companies of the Naftogaz Group. Hence, there were also problems in the past with payments for import supplies and the accumulation of debts, which were formed through the draconian conditions of each contract.

Therefore, all major parties regarding Russian gas transit to Europe at different times referred to supply and/or transit risks to support negotiating positions or justify their actions. This includes EU-Russia relations, prices, and storage conditions.

Accordingly, European companies that purchased significant volumes of Russian gas remained supporters of transit diversification. This was demonstrated in September 2015 by the shareholder agreement between Shell, Uniper, BASF, Engie, OMV, and Gazprom for the construction of Nord Stream 2. The project was completed in September 2021 but was never put into operation. Germany stopped the approval process on February 22, 2022, two days before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, when Russia recognized “L/DPR.”

Naftogaz of Ukraine required regular billion-dollar subventions from the state budget for years. After the victory of the Revolution of Dignity and the arrival of new managers in the company, the situation changed dramatically. Already by the results of 2016, the Naftogaz Group became the largest taxpayer (12% of state budget revenues).

Moreover, the Ukrainian side won several lawsuits worth billions of dollars — the claims, in particular, concerned violations of transit contracts, prices, and illegal expropriation of assets in occupied Crimea.

Europe Had Time to Prepare

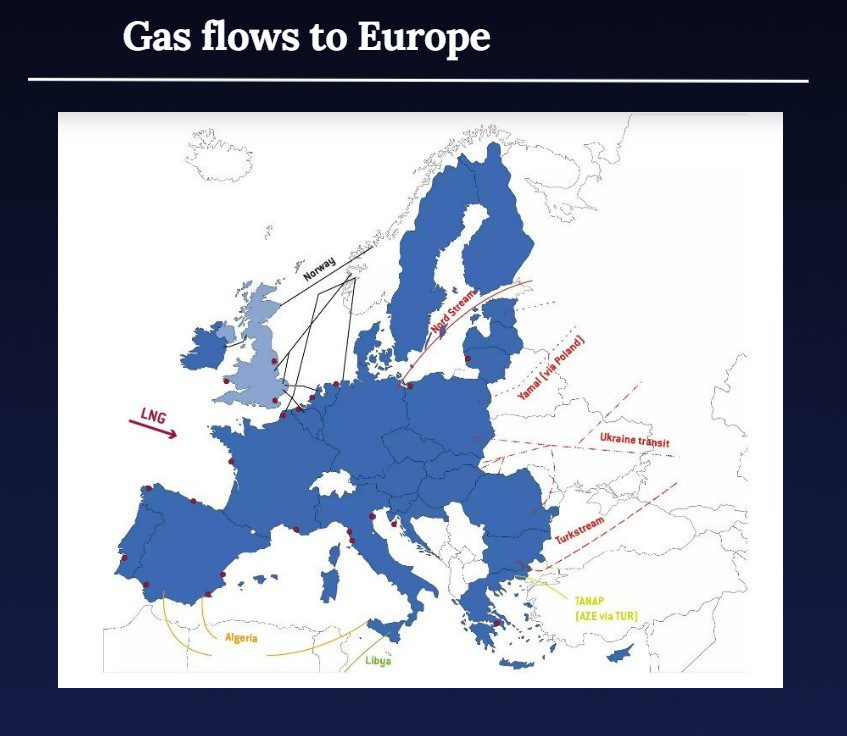

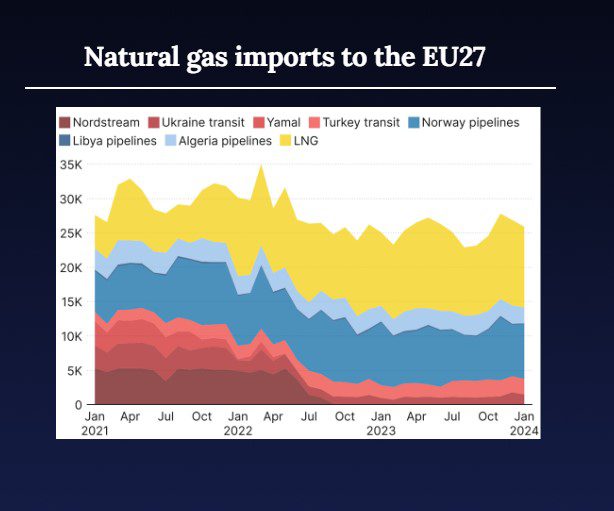

Before 2022, Gazprom annually supplied about 150-155 billion cubic meters of gas to the EU, of which 90 Bcm were transported through the Ukrainian gas transportation system in 2019. This was the last year of the old contract between Naftogaz and Gazprom.

After signing the new five-year agreement, transit volumes were halved. Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine further affected this process, reducing transit by more than a quarter — to 15 Bcm in 2023 and to 10 Bcm for the first eight months of 2024.

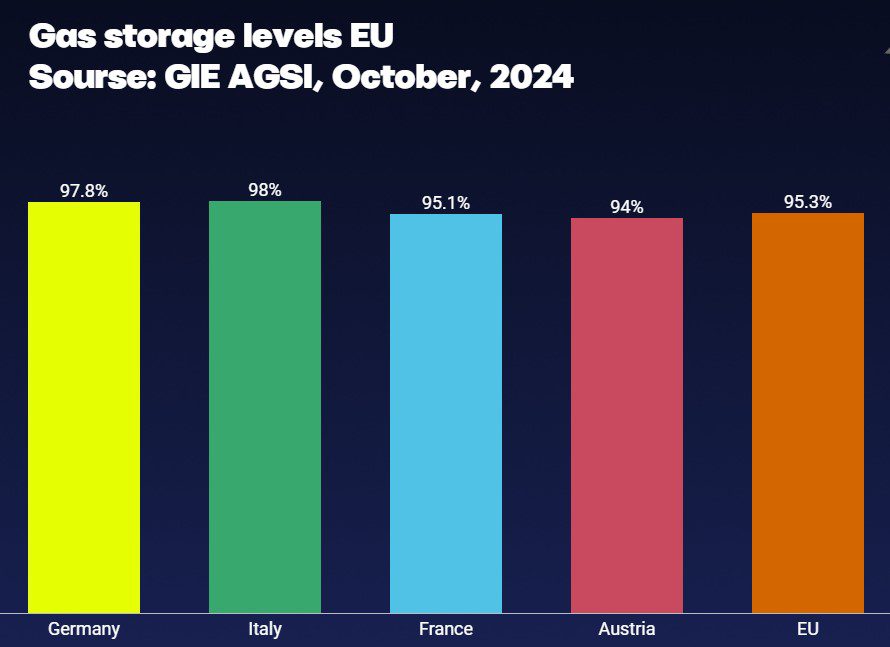

This became possible thanks to active diversification of natural gas supplies to European countries. Having rejected significant volumes of Russian pipeline gas after the start of the Great War, Europe partially replaced it with Russian liquefied gas (LNG) supplied by tankers. Taking LNG into account, Russia accounts for 15% of European gas, 30% of EU receives from Norway, 19% comes from US LNG. The European Union states it wants to completely get rid of gas from Russia by 2027.

However, some states were more dependent on Ukrainian transit — Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic, and Austria. But does this dependency still persist?

Austria

Historically, Europe’s gas network was built to transport gas from east to west.

Due to gas transportation corridor capacity limitations in many European regions, it’s impossible to ensure the transportation of significant gas volumes from west to east or from the sea to the central part of the continent.

Except for Baltic Pipe construction, which provided Poland and Denmark access to Norwegian gas, the largest projects in recent years were carried out by Gazprom (Nord Stream, Turkish Stream). The goal was to bypass the restrictions of the EU’s Third Energy Package to maintain the fragmentation of the European market and its dependence on Russian gas.

To achieve this goal, Russia invested several tens of billions of dollars in building redundant gas pipelines that allowed bypassing Eastern and Central European countries and supplying most European countries separately from each other. Meanwhile, Gazprom avoided connecting new gas pipelines to the existing European network and sought to deliver its gas as close as possible to end consumers without opening market access to competitors.

The region thus formed, isolated from alternative suppliers with its center in Baumgarten, requires about 90 billion cubic meters of gas per year, corresponding to 2/3 of Russian gas supplies to Europe. In parallel, Gazprom acquired the main gas storage facilities in this region, thus limiting the possibilities of accumulating gas from alternative sources during the injection period.

In February 2022, Austria imported 79% of its gas from Russia. In 2024, the average total share of Russian gas in Austrian imports was 90%. Gazprom’s gas comes to Austria under a long-term contract (valid until 2040) with local energy company OMV; according to Bloomberg, these supplies account for about half of all Gazprom’s exports to the EU. The country, like other EU members, intends to completely abandon Russian gas by 2027.

Hungary

Hungary mostly receives the same Russian gas through Turkish Stream, and imports through this route are expected to increase in the future. Budapest has also concluded short-term contracts for liquefied natural gas imports with Turkey. And increasing transportation capabilities of liquefied natural gas coming from the Croatian port could further strengthen the country’s supply security, analysts at Hungary’s Makronom Institute note.

So, at minimum, Hungarians are secured for the upcoming heating period.

Czech Republic

The transit stop should not have any consequences for the heating season in the Czech Republic either, Czech analyst of the Association for International Affairs Pavel Havlicek tells Zaborona.

“The Czech Republic has invested heavily to completely abandon Russian gas. Back in February 2022, the country was dependent on Russian blue fuel by more than 90%, and in a year this dependence fell to less than 5%. And we actually no longer need Russian natural gas,” he says.

Since 2023, Prague has been receiving natural gas from Norway, and liquefied gas by sea through Belgium and the Netherlands. However, in the last few months, there has been a sharp increase in Russian natural gas supplies due to its lower prices compared to what is imported through the LNG terminal in the Netherlands, notes Havlicek.

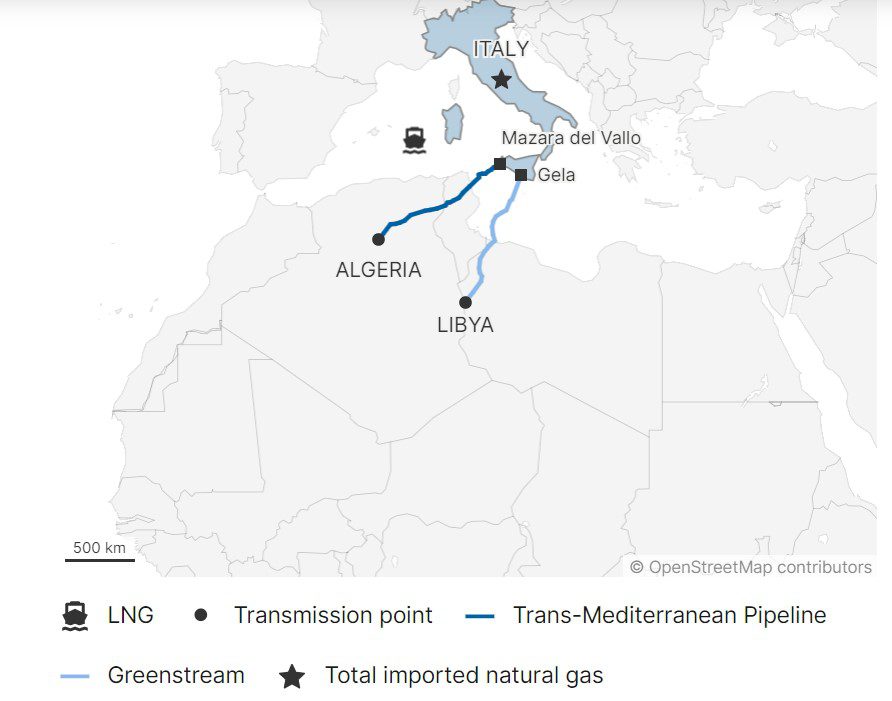

In his opinion, the biggest problem still lies in other Central-Eastern European countries’ dependence on Russian gas, namely Austria and Slovakia. Although Austria still receives a significant portion of its gas through Ukraine, it can import gas from Germany and Italy. The latter receives most of its gas from Algeria (Trans-Mediterranean Pipeline) and Libya (Greenstream).

Slovakia

Slovakia has no problems either, assures Radovan Potočár, editor-in-chief of the Slovak professional publication Energie Portal. According to him, the Ukrainian government has been informed about the decision to stop Russian gas transit since the summer 2023. Therefore, Slovak suppliers had relatively enough time to find alternative sources.

Photo: energie-portal.sk

“Slovakia can receive gas from western, northern, and southern directions, so the country does not depend on the route through Ukraine and, accordingly, on Russian gas. Alternative routes are relatively more expensive than transit through Ukraine, which means additional costs. However, the gas itself as a commodity from the US, Qatar, and other sources is generally not more expensive than Russian gas. Wherever gas comes from, its price depends on market prices,” he explains in a comment to Zaborona.

Gas Prices in Europe Will Rise, but Not Due to Transit Stop

Currently, the Slovak government has not yet decided what gas prices will be in 2025 and how much households will pay, notes Radovan Potočár. “One option is to increase gas prices for households by about 30%, another option is that the government will compensate for this increase from state funds, as it was in 2023-2024,” the expert said.

At the same time, he adds, the increase would have occurred regardless of whether Ukraine stops its transit or not, as it is based on stock market indicators. On the other hand, the transit stop will lead to an even higher increase in the final price.

“Although the main reason for the price increase lies in the stock market and commodity prices, politicians, including current government leaders, may be inclined to present this as a consequence of the transit stop,” believes Potočár.

Unfortunately, this will be manipulated by both the pro-Russian government in Hungary and the opposition in the Czech Republic, adds Pavel Havlicek. “Socio-economic aspects are particularly sensitive in the pre-election period, which we are entering a few months [general parliamentary elections are expected in October 2025], so this may create space for abuse by populist and anti-system forces in the country,” says the analyst.

Can Transit Through Ukraine Be Preserved?

One of the options for continuing transit from Russia through Ukraine could be direct contracts between European companies for gas supply with both Gazprom and the Ukrainian side. In this case, companies would take gas at the Russian-Ukrainian border and independently negotiate with Kyiv about its pumping further west.

Another option is European companies purchasing Azerbaijani gas, which would then be transported through Russia and Ukraine to Europe. However, currently, there is no direct gas pipeline from Azerbaijan to Ukraine.

“So Baku will act here as an intermediary company: Azerbaijanis will buy gas from Russia, conclude a transit agreement with Ukraine, and will resell it to Europe as Azerbaijani. This is quite a dangerous scheme, as Azerbaijan is quite a strong ally of Russia,” emphasizes Volodymyr Omelchenko, Director of Energy Programs at the Razumkov Centre.

There is also a third option. Ukraine offers an alternative to traditional transit: storing gas in Ukrainian USFs with subsequent use by the owner at their discretion. This proposal has been made to both Azerbaijan and Slovakia.

Under the scheme, Azerbaijan could inject gas into Ukrainian storage facilities and sell it on the European market depending on demand. Slovakia could buy gas at the border, store it in Ukraine, and use it as needed. Such a scheme would legally be considered not transit but re-export of gas from Ukraine.

Gas Hub in Ukraine

Ukraine’s gas transportation system is a very valuable asset that would be a shame to lose. But it’s not just about transit, as there has long been talk about the possibility of turning Ukraine, which has the largest gas storage facility in Europe, into a gas hub.

[INFOGRAPHIC_Potential tools to ensure EU gas demand while refusing gas imports from Russia by 2030]“This is a gold mine. If we earned 800 million dollars a year on transit, maybe up to one billion, then with storage we can earn from 6 to 12 billion dollars per year,” declares Andriy Zakrevsky, Chairman of the Board of the Oil and Gas Association of Ukraine. The Kremlin understands this perfectly well, which is why they are carrying out attacks on the gas transportation system. “The Russian strikes have no impact on the operation of the gas transportation system and the storage facilities themselves because they are deep underground. The enemy is destroying the surface infrastructure, which can be restored quite quickly, and this is much cheaper than what these strikes cost Russia itself [approximately $15 billion]. But why are they doing this? The Russians want to present Ukraine as an unreliable partner that cannot ensure the security of storage facilities. But we need to explain that this is not the case, and the gas storage facilities are completely safe since they are underground,” the expert concludes.

With the support of Mediaset