The full-scale war in Ukraine has triggered an outflow of Ukrainians abroad, mostly to the West. According to data of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), as of mid-June 2024, almost 6 million Ukrainians are living in Europe.

The largest number of Ukrainian citizens have now been granted temporary protection in Germany — 1.1 million, in Poland — 957,000, and in the Czech Republic — 346,000. Notice that Germany took the lead from Poland, which shares a common border with Ukraine and a close language, only in 2023. The intra-European migration was driven by higher social benefits, higher wages, and integration initiatives of the German government. Other reasons for moving include feedback from Ukrainians who had settled here before and the desire to provide a quality European education for their children.

Finding work and learning new languages, integrating into European communities and trying to maintain mental health amidst worries about relatives and friends who remain in Ukraine are the things that unite Ukrainian refugees abroad. There are also generalised refugee stereotypes within Europe and misunderstandings at home, which leads to the loss of a common identification factor.

Ukrainians abroad and Ukrainians in Ukraine

Today, more than 280 million people — 3.6% of the world’s population — live in countries other than their birthplace, but not all of them are refugees. Together, migrants worldwide make up the fourth most populous country in the world. Moreover, more people are ready to migrate if they have the opportunity. The main factors are socio-economic (for conscious migration) and security, as in the case of Ukrainians.

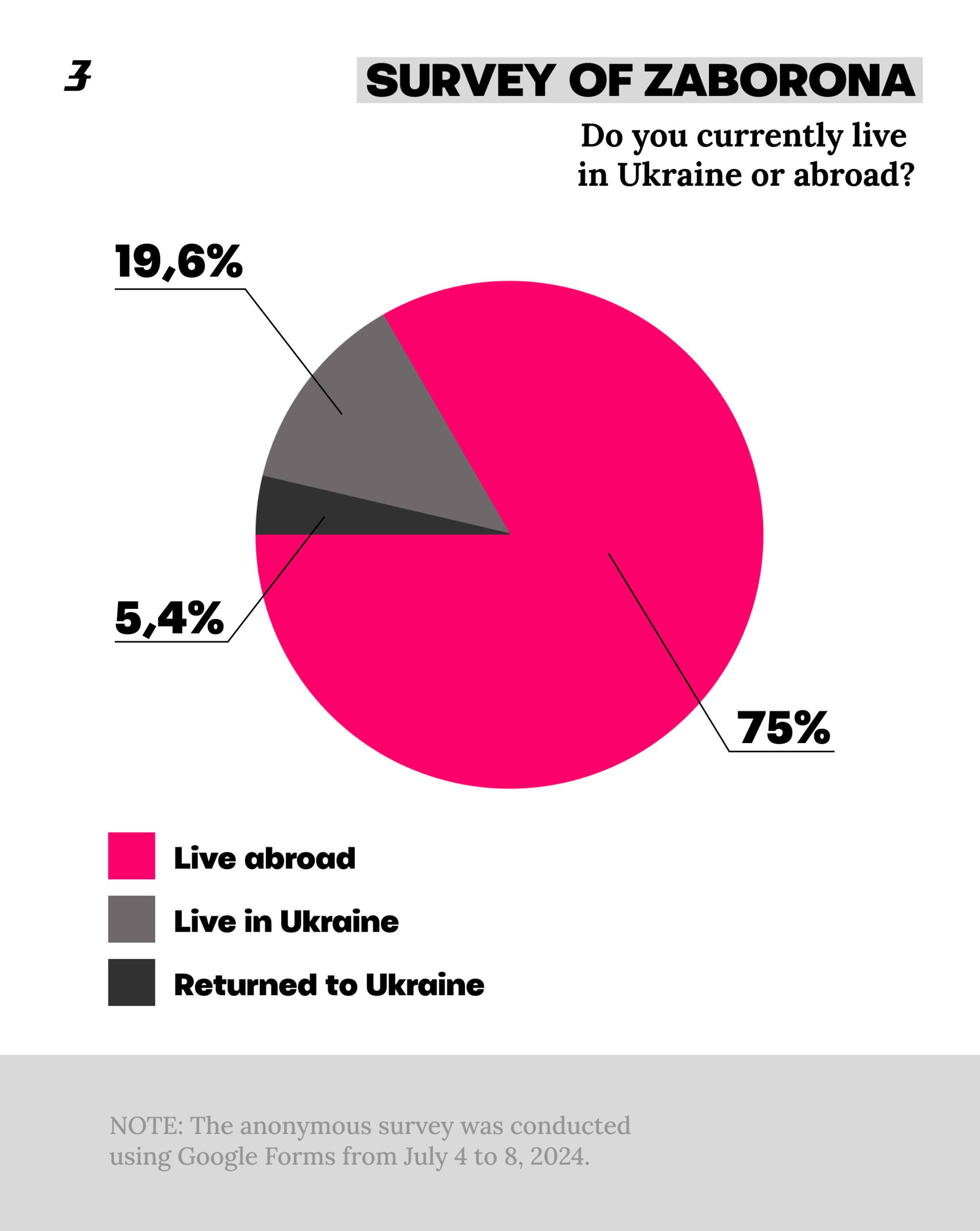

Zaborona conducted a survey among its readers, offering them to share their opinions anonymously about their choice to stay in Ukraine or leave and stereotypes about migration.

Infographic: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Data: Zaborona

According to our survey, the reasons for travelling abroad include:

- war;

- personal and family safety;

- occupation or threat of occupation of the place of residence, fear of re-occupation (for residents of the territories seized by Russia in 2014);

- availability of work abroad;

- availability of work abroad;

- loss of home and family;

- no possibility to realise one’s potential in Ukraine;

- uncertainty that state institutions act properly.

Ukrainians who stayed in the country explained their choice as follows:

- no possibility to leave;

- family;

- support of the state in this way;

- staying in a relatively safe place;

- moral values.

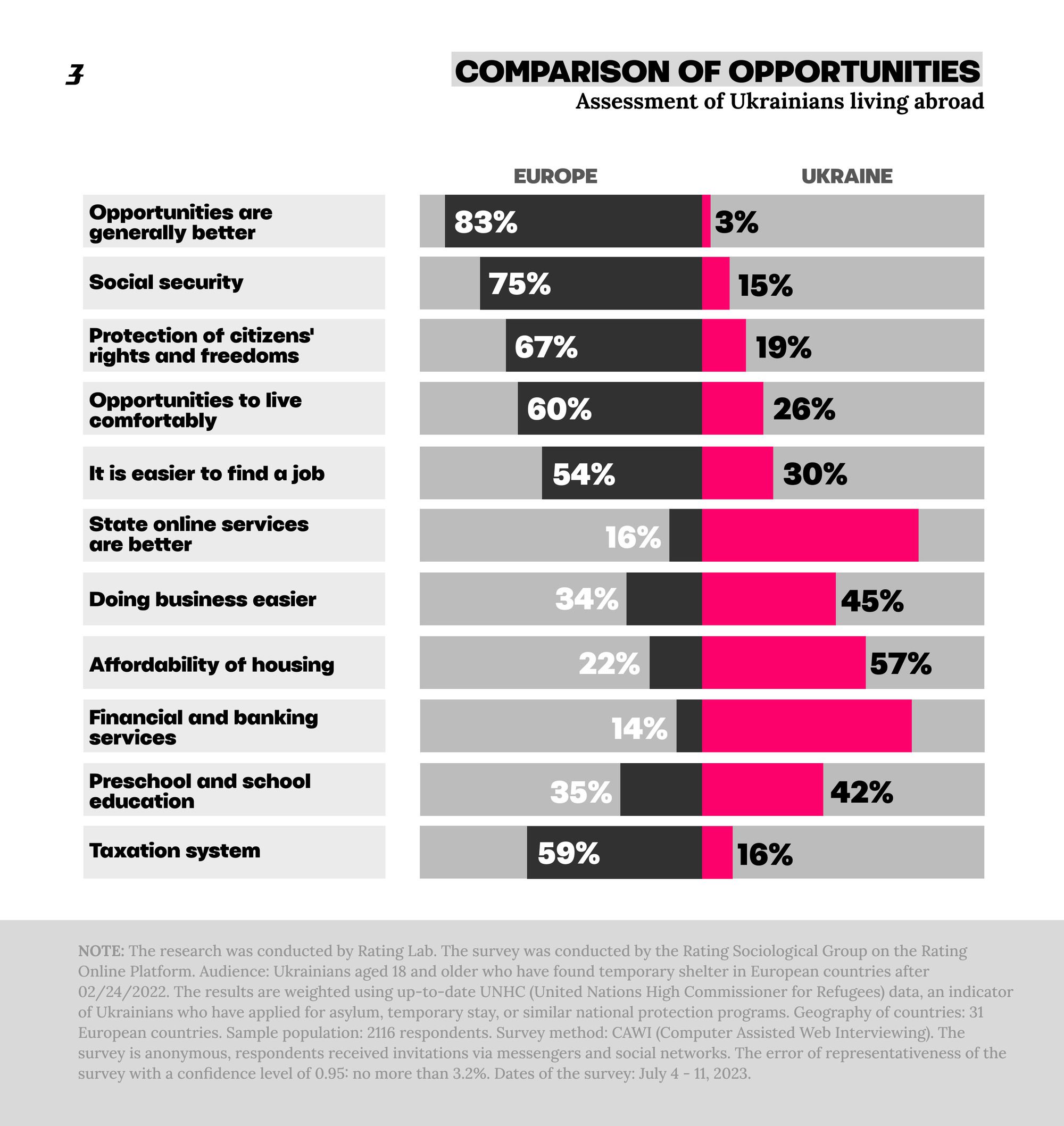

The information from Zaborona’s survey coincides with the data of the Rating Lab. When comparing opportunities, Ukrainians summarise that Europe offers jobs, protection, income, comfort, infrastructure, while Ukraine offers services, including medical and partly educational, business opportunities, and affordable housing. Success is equally possible to achieve in both Ukraine and Europe.

Infographic: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Data: Rating Lab

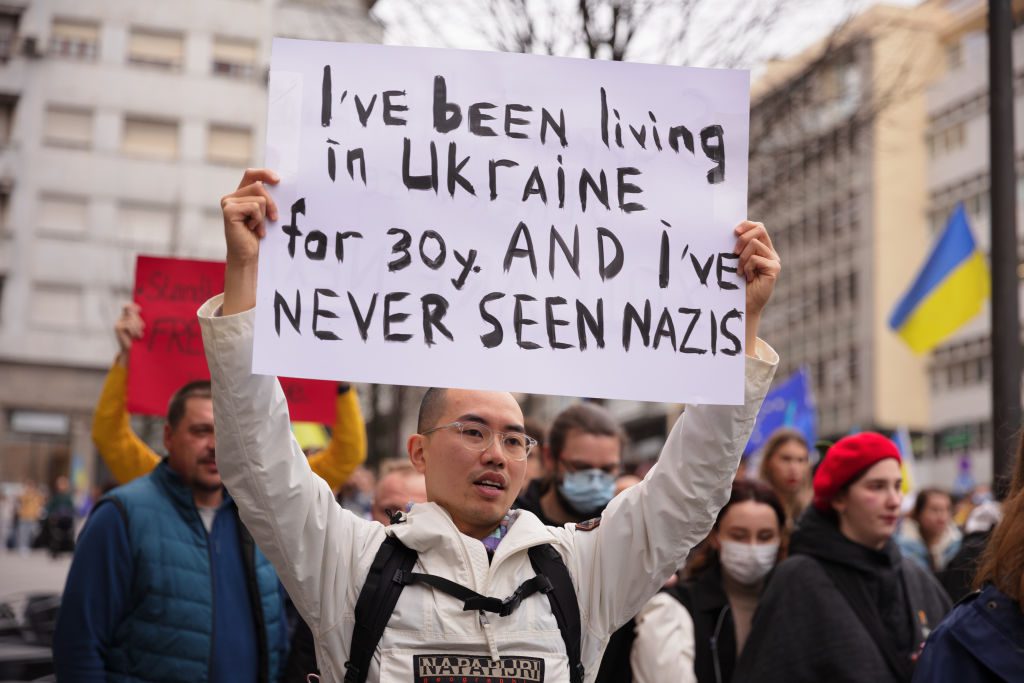

Myth 1: Migrants take the jobs of locals

Talks about Ukrainian refugees trying to take the jobs of locals in the country where they have temporarily resettled appear from time to time on social media. In particular, this phenomenon was studied by Ada Tymińska, a human rights activist at the Helsinki Human Rights Union in Poland, in her report They will come and take away: anti-Ukrainian hate speech on Polish Twitter. Although at the time of the report’s publication in April 2023, sympathy for Ukrainians was not questioned, the researcher predicted that anti-Ukrainian insults would definitely intensify in a more favourable situation when active support for refugees would naturally decrease due to fatigue.

‘Changes in attitudes arise only out of fear for one’s own well-being,’ says Ada Tymińska. — ‘If a politician who is not very sensible suddenly declares that Ukrainians will come and take away their jobs or social security, someone will agree with him.’

By the way, anti-Ukrainian sentiment in Poland is fuelled by the pro-Russian far-right Confederation party, which actively opposes the ‘Ukrainization of Poland’, blocks checkpoints on the Polish-Ukrainian border and calls for a reduction in refugee payments. Meanwhile, farmers, whose interests the Confederation supposedly protects, are already complaining about the lack of seasonal workers.

‘I advise to recall the statements of Polish farmers in the spring that there would be no one to pick strawberries or work in low-skilled jobs,’ Vasyl Voskoboinyk, president of the All-Ukrainian Association of International Employment Companies says. — ‘Usually, people who come here cannot compete for high-paying jobs but come to those niches of the market where there is less demand among the locals. Similarly, Poles preferred to go to Germany to pick asparagus because such work is better paid in neighbouring countries.’

The Polish Economic Institute (PEI) claims that the employment rate of Ukrainians in Poland is currently the highest among OECD countries. However, Ukrainian refugees face various challenges in the Polish labour market and sometimes experience unequal treatment.

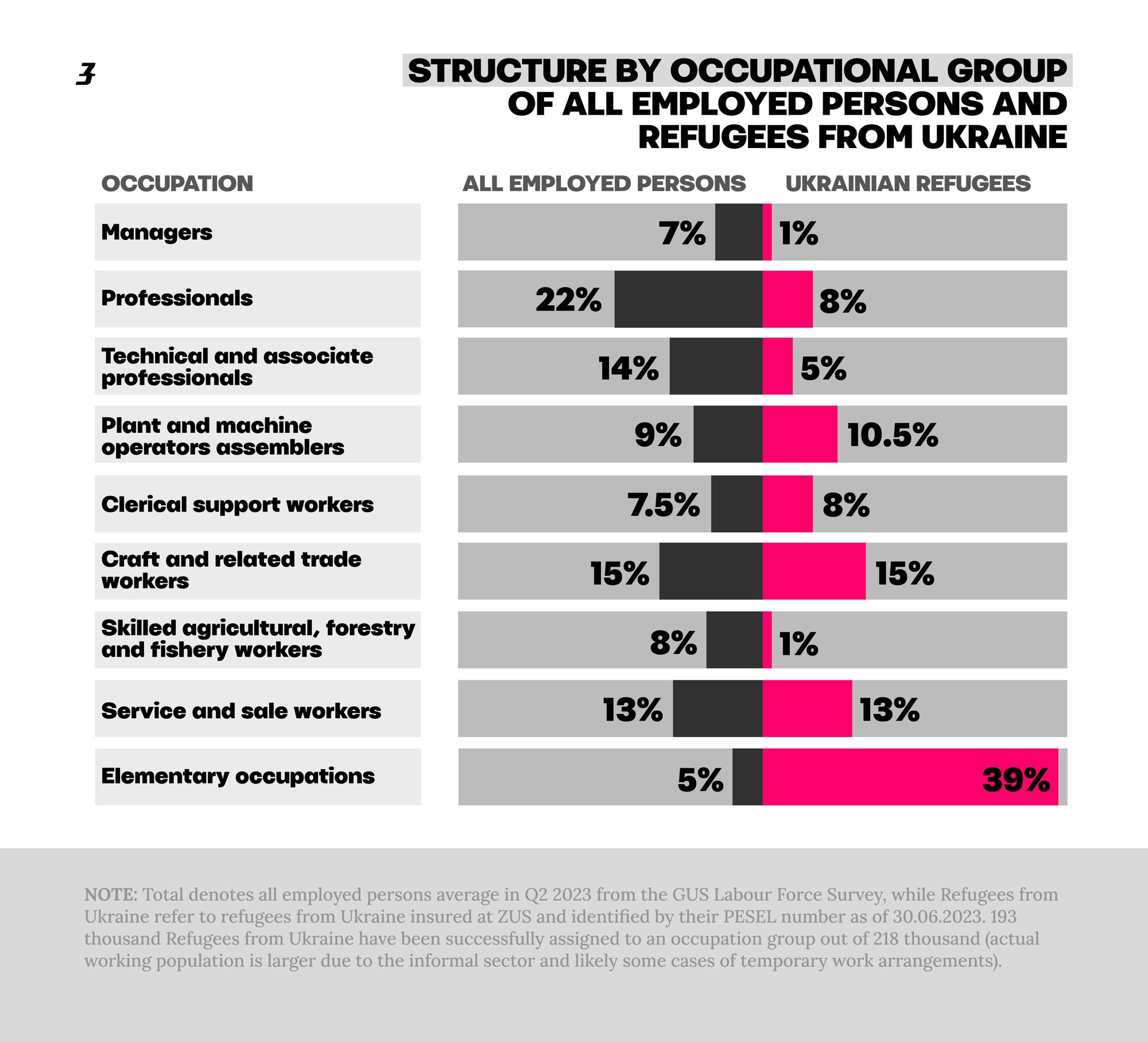

Infographic: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Data: DELOITTE

‘It is more difficult for refugees to get their qualifications recognised, and they often work below their skills or in the shadow economy. Discrimination on the basis of nationality is not a widespread phenomenon,’ Radosław Zyzik, Senior Advisor at PEI Behavioural Economics explains. — ‘Those who have experienced it or heard about cases of discrimination point to low remuneration, exploitation of their vulnerability in the labour market, unequal treatment and workload, and harmful stereotypes.’

Thus, as part of the experiment, (a PEI report ‘Refugees from Ukraine in the Polish Labour Market: Opportunities and Obstacles, March 2024) found that in several industries where no special qualifications are required, employers are less likely (30% less) to respond to CVs sent by Ukrainian women compared to CVs sent by Polish women. The difference, analysts say, is a signal of potential discrimination at the initial stage of employment.

Marcin Kołodziejczyk, Director of International Recruitment at the EWL Migration Platform, emphasises that Poland has been experiencing a shortage of workers for a long time. And the need for staff is so great that people from all over the world — including Latin America and Asia — come to work in the country.

‘The needs of the Polish labour market for the next five years are approximately half a million employees,’ says Marcin Kołodziejczyk. — ‘Today, when the unemployment rate in Poland is the second lowest in Europe (3%), the shortage of personnel is felt in almost every industry, and the economy is growing (+2% in the first quarter of 2024). This is not about competition, but about the demand for a large number of employees. There will be enough work for everyone.’

The Ukrainian House Foundation in Warsaw has also recorded a consistently low unemployment rate in Poland in recent years. According to information from the Central Statistical Office (Główny Urząd Statystyczny), the influx of refugees to Poland did not have a significant impact on its level.

‘Another thing is that recent sociological surveys show that this stereotype is not as common among Poles as it seems,’ Oleksandr Pestrykov, an expert at the Ukrainian House says. He refers to another study by the Polish Economic Institute.

According to the survey, only 30% of respondents believe that foreigners pose a threat to Polish workers. 23% of respondents believe that foreigners can compete with skilled workers. 56% believe that the threat is only for low-skilled workers.

‘The locals are more afraid of wage dumping. Where a Pole demands a higher wage, Ukrainians will do the job for less money,’ says Pestrykov. — ‘The Polish domestic economy depends on cheap labour. This is a competitive advantage, but also a problem. It hinders robotisation and automation of industry, and workers do not want to be cheap labour forever.’

Over the past two years, according to an expert from the Ukrainian House Foundation, the phenomenon of labour migration has almost disappeared. Ukrainians in Poland are looking for stable jobs with days off, sick leave and holidays. And this is where a new problem arises: Polish society is ready to see Ukrainians as construction workers and waiters, but not so much as lawyers, clerks, teachers, and shopkeepers.

‘I’ve also been accused of not paying taxes because Ukrainians don’t work or work unofficially,’ says Inna, who ended up in Austria. — ‘I answered that I would be happy to work full-time officially, because I have an Austrian diploma, more than ten years of Ukrainian work experience in my speciality, and fluent German. But where is the job?’

By the way, the Czech Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs also says that Ukrainians do not take away jobs. According to its data, four out of five Ukrainians have found work in unskilled and unstable positions.

‘Europe is currently experiencing an accelerated demographic ageing process. There is a shortage of labour everywhere,’ Ella Libanova, Academician of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Director of the Ptoukha Institute for Demography and Social Studies comments. — ‘That’s why business is really interested in having more workers, more working heads. And Ukrainians are not competing with Europeans in terms of employment — they have different niches. And this is how it always happens: Migrants, especially first-generation ones who have just arrived, take the jobs that are given to them. They do not displace the locals. Yes, there is some competition, but it’s not as much as some people would like to say. It’s just twisting the facts.’

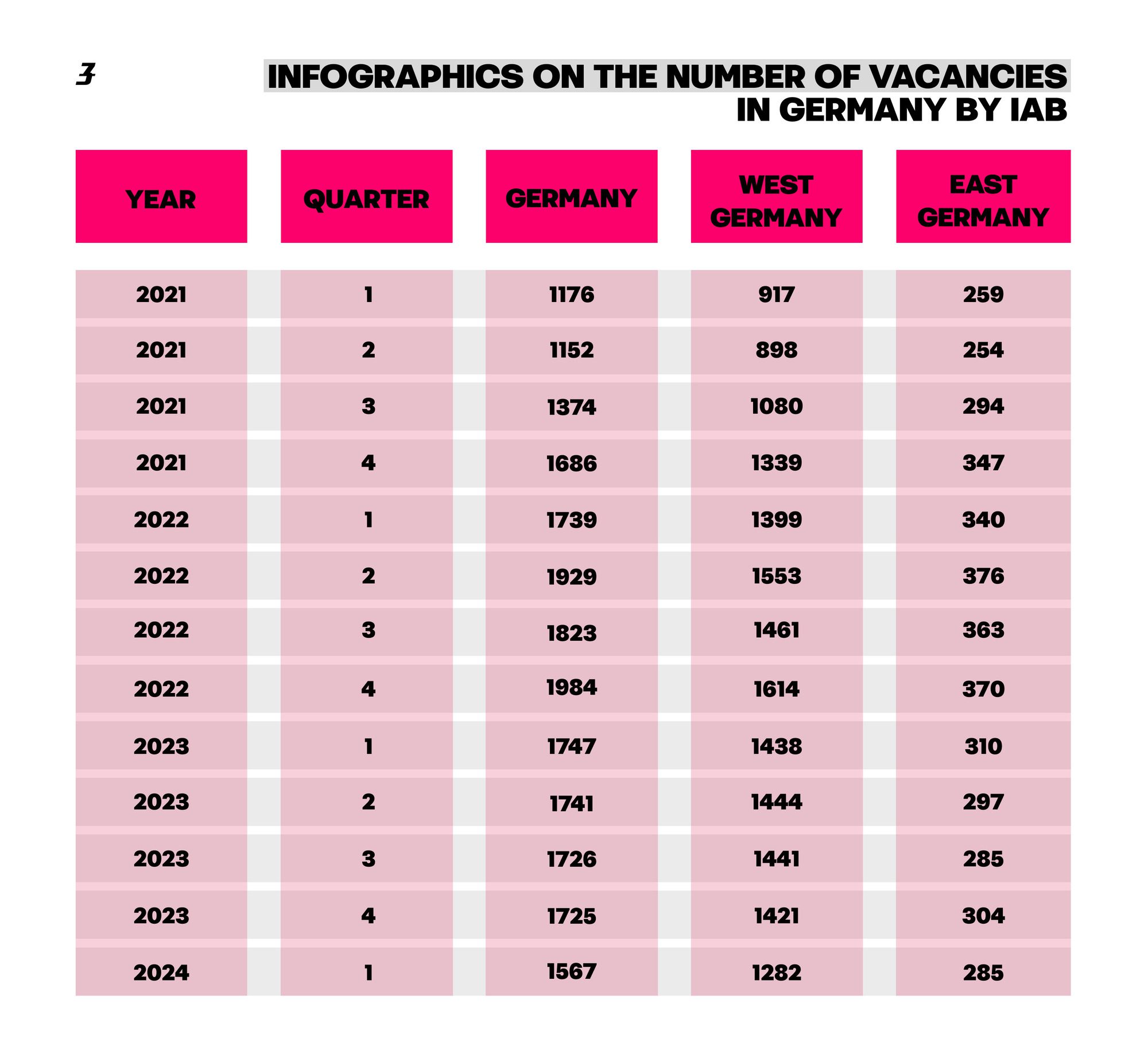

Infographic: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Data: IAB

The Centre for Economic Strategy says that there is no fixed number of jobs in the economy, whether held by locals or migrants.

‘Immigrants stimulate the economy of the host country, because they also buy goods and services in that country,’ Daria Mykhailyshyna, senior economist at the Centre for Economic Strategy comments. — ‘In order to produce more goods and services, more jobs are needed. Therefore, immigrants usually do not take the jobs of locals, but help economic growth, which creates more jobs. In addition, many European countries, where a large number of Ukrainians have moved to, have a problem with a lack of labour force due to low birth rates and an ageing population, so Ukrainian migrants can help fill this gap.’

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

Myth 2: large amounts of budget funds are spent on IDPs, which could be used for community development and other local expenditures

The stereotype that Ukrainians move to Europe for financial assistance and stay for social benefits is quite widespread among both locals and Ukrainian citizens who stayed at home (as evidenced by the responses in Zaborona’s survey).

‘In Germany, many people have the opinion that Ukrainians stay here only to receive social benefits and that they do not want to work. I am involved as an interpreter for Ukrainians during live conversations in various institutions. And I am very sad that this stereotype is often justified,’ the Ukrainian woman shared her experience.

However, almost all of those who took part in the survey and belong to the group of those living abroad say they are working. Women with children emphasise that the payments are very small: ‘It’s enough only for nappies and baby feeding’.

In Poland and Czech it has already been calculated that Ukrainian refugees who found themselves in these countries at the outbreak of full-scale war have more than compensated for the money spent on them.

The Polish government spent PLN 15 billion (approximately EUR 3 billion) on state support for refugees from Ukraine in 2022 and about 5 billion in 2023. This assistance also includes a one-time payment of PLN 300 (EUR 70), a monthly child benefit of PLN 500, which has increased to PLN 800 (EUR 187) since January 2024. However, only 7% of Ukrainian refugees live on Polish social assistance, which is one of the smallest in the EU.

Almost 80% of Ukrainian citizens who arrived in Poland due to the full-scale invasion are employed and support themselves. Research by the EWL Migration Platform confirms that Ukrainian refugees started looking for work from the first weeks of their stay in Poland, and changed jobs throughout the year, seeking professional growth opportunities.

In the Czech Republic, the balance of income and expenditure on support for Ukrainian refugees looked like this: In 2023, CZK 21.6 billion (EUR 858 million) in expenditures still exceeded CZK 21 billion in income. However, in the first quarter of 2024, revenues outweighed expenditures — CZK 6.4 billion (approximately EUR 254 million) in taxes and fees against CZK 3.5 billion in aid. By the way, 88% of Ukrainian refugees work in the Czech Republic.

There are about 700,000 refugees with Ukrainian passports registered with German employment centres. All of them can receive EUR 563 per month. There is also a child benefit.

According to a study carried out by the Institute for Employment Research (IAB), employment of Ukrainian refugees in Germany requires an optimal 10 years of integration.Then the average employment rate among Ukrainian refugees in the country will reach 55%. In five years, the figure can be expected to reach 45%. Employment is hampered by the high proportion of single mothers and the relatively poor health of refugees.

‘The German government says that if 20% of Ukrainians are employed now, they will be satisfied with an increase to 40%,’ Vasyl Voskoboinyk, president of the All-Ukrainian Association of International Employment Companies says. — ‘The low percentage of employed people in Germany is due to the language requirements, and they also focus on highly skilled work, giving Ukrainians the opportunity to improve their skills or retrain to work not only with their hands. Now the government is simplifying the conditions for employment, and the German language requirements are being reduced.’

He believes that Ukrainian refugees are not the kind of people who will rely on social assistance in Europe.

‘When people went abroad in search of asylum, they were not looking for work, but were trying to get as far away from the war zone as possible,’ Vasyl Voskoboinyk explains. — ‘So, it is inappropriate to say that Ukrainians came and became social dependents. There is a certain percentage of them. But no matter how much social assistance is paid, it is not enough for normal functioning. If there is not enough money, Ukrainians will look for work. Some are employed illegally, but they earn money.’

A man with his dog evacuates the city of Vovchansk, which is constantly shelled by Russia, Kharkiv region. North-eastern Ukraine, 12 May 2024. Photo: Ukrinform/NurPhoto via Getty Images

According to data from a survey by the Centre for Economic Strategy, as of November 2022, 73% of Ukrainian refugees in Europe received payments, while as of January 2024, only about 40% did.

Almost half of those surveyed in Germany (44%) and the Netherlands (40%), where social benefits are among the highest in Europe, say that although financial assistance allows them to support themselves in their host country, they decide to find a job.

This is the key finding of the study ‘Unleashing the Potential: Ukrainian Citizens in Germany and the Netherlands’, conducted by the EWL Migration Platform and the Centre for East European Studies at the University of Warsaw.

‘Many countries in Europe and around the world provide assistance to Ukrainians who left because of the war,’ Daria Mykhailyshyna, senior economist at the Centre for Economic Strategy says. — ‘However, over time, the number of Ukrainians receiving assistance has significantly decreased both due to changes in the policies of the countries hosting Ukrainians and because many of them have already found jobs and do not need assistance. In addition, the economies of the host countries benefit more than they spend on aid.’

Meanwhile, the CES notes that Ukraine’s labour market is experiencing all the challenges of a full-scale war. The economic shock of the beginning of the Russian invasion caused a drop in both demand and supply of labour — businesses did not hire and people did not apply for jobs. Subsequently, demand for labour began to recover, but slowly; at the same time, the number of people looking for a new job soared in the summer of 2022 and exceeded the average for 2021. However, the trends diverged from there: the need for labour has been recovering alongside the economic recovery, while the activity of job seekers has been declining, not least due to Ukrainians’ migration abroad and mobilisation into the Defence Forces.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

Myth 3: Migrants do not pay taxes and do not help the economy to develop

As early as May 2022, Oxford Economics predicted that if 650,000 Ukrainians remained in Poland, GDP could grow by 1.2% by 2030, and if 1 million Ukrainians remained, by 2%, compared to the scenario without forced Ukrainian migrants. Similar forecasts were made by the National Bank of Ukraine, which in 2022 estimated that, thanks to refugees from Ukraine, by 2026, the GDP of Poland and the Czech Republic would increase by 2.2-2.3% compared to the baseline scenario, and Germany by 0.6%-0.65%.

While in 2022, the state budget revenues from Ukrainians in Poland amounted to 0.8-1.0%, last year it was already 1.3-1.6%. In monetary terms, this amounts to PLN 10.1-13.7 billion (approximately EUR 2.34-3.18 billion) in 2022 and PLN 14.7-19.9 billion in 2023. The study ‘Analysis of the Impact of Refugees from Ukraine on the Polish Economy’ was commissioned by the UN and conducted by the international consulting company Deloitte in cooperation with the EWL Migration Platform.

A report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) says that in the long term, when the economy fully adapts, this figure will rise to 0.9-1.35%.

‘This is a significant impact on the Polish economy, given the challenges posed by Russian aggression, the general situation and the significant shortage of personnel in Poland,’ Marcin Kołodziejczyk, Director of International Recruitment at the EWL Migration Platform says. — ‘Ukrainians are saving the Polish labour market — both those who came to Poland before the full-scale invasion and war refugees.

Thus, since 2022, Ukrainians in Poland have been helping to develop the economy by paying PLN 10-14 billion in taxes, and in 2023 – PLN 15-20 billion in taxes. Most Ukrainian refugees also help their families in Ukraine, donate to the Armed Forces or volunteer, according to EWL reports in Poland and Germany.

‘Recently, there was a study by experts from the UK, where there are significantly fewer Ukrainian migrants,’ Ella Libanova, a member of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine and director of the Ptoukha Institute for Demography and Social Studies says. — ‘They report that the additional 0.2% of GDP is precisely the contribution of Ukrainian migrants. And this is serious for UK. Ukrainians live in Europe, work, pay taxes and spend money. It is known that every zloty spent in Poland works for the Polish economy.’

According to a survey conducted by the Centre for Economic Strategy, as of January 2024, 45% of Ukrainians who went abroad were employed or became entrepreneurs, and therefore pay taxes on their labour income or business profits. All migrants pay at least consumption taxes and value added tax when they buy any goods and services.

‘Let’s not forget that in Poland and the Czech Republic, the money paid to people who provided housing was received by the locals,’ Vasyl Voskoboinyk, president of the All-Ukrainian Association of International Employment Companies emphasises. — ‘If we talk about the Polish 800+ per child allowance [a monthly payment of PLN 800 for a child under 18], it is clear that this money will be used for that same child, it will go to the budget and remain in circulation in the country and will contribute to the development of the economy.

‘In order not to be bound by anything, I started my business from scratch in Poland,’ says Yelyzaveta. — ‘I found the first pair of shoes for my mother in a dumpster. I also found a coffee machine and a kettle for my empty apartment. At first, I travelled to orders with a small suitcase of tools, and now my permanent make-up studio in Warsaw employs ten artists. We have a high price, and 80% of our clients are local.’

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

Myth 4: Worsening of the crime situation

Although this stereotype is more likely to be applied to people from non-European cultures, some locals may generalise the concept of ‘refugees’ and apply this thinking to everyone.

At the beginning of 2024, the Ukrainian House Foundation in Warsaw was forced to publicly respond to the Rzeczpospolita article ‘The Dark Side of Migration. Foreigners in Poland drive drunk and violate prohibitions.’ The article stated, in particular, that ‘the influx of thousands of foreigners, which increased after the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, was reflected in crime statistics.’ In an open letter to the editor, the foundation reasonably suggests that there were probably some reasons and prerequisites (events, alarming survey results, xenophobic statements by politicians) that prompted Rzeczpospolita to publish statistics on crimes committed in Poland by non-citizens.

‘It would be fair to state these reasons and explain to the reader your intentions in writing the article,’ the letter says. — ‘It is disturbing that a serious newspaper that shapes public opinion is resorting to ethnic profiling and manipulating cultural differences.’

The Foundation’s experts worked with the figures published in the article and concluded that the 17,278 foreigners who committed crimes in 2023 were responsible for only about 2% of all crimes. In addition, 3,240 thefts committed by foreigners accounted for approximately 3% of all thefts in Poland, and 2,451 drug possession charges accounted for 4% of all such charges. Moreover, the growth rate of crime among migrants is 7.7 times lower than the growth rate of the foreigner group itself.

‘The stereotype about the deterioration of the crime situation due to refugees has only been encountered among Polish journalists,’ Oleksandr Pestrykov, an expert at Ukrainian House comments. — ‘They often like to emphasise the nationality of suspects and convicts.’

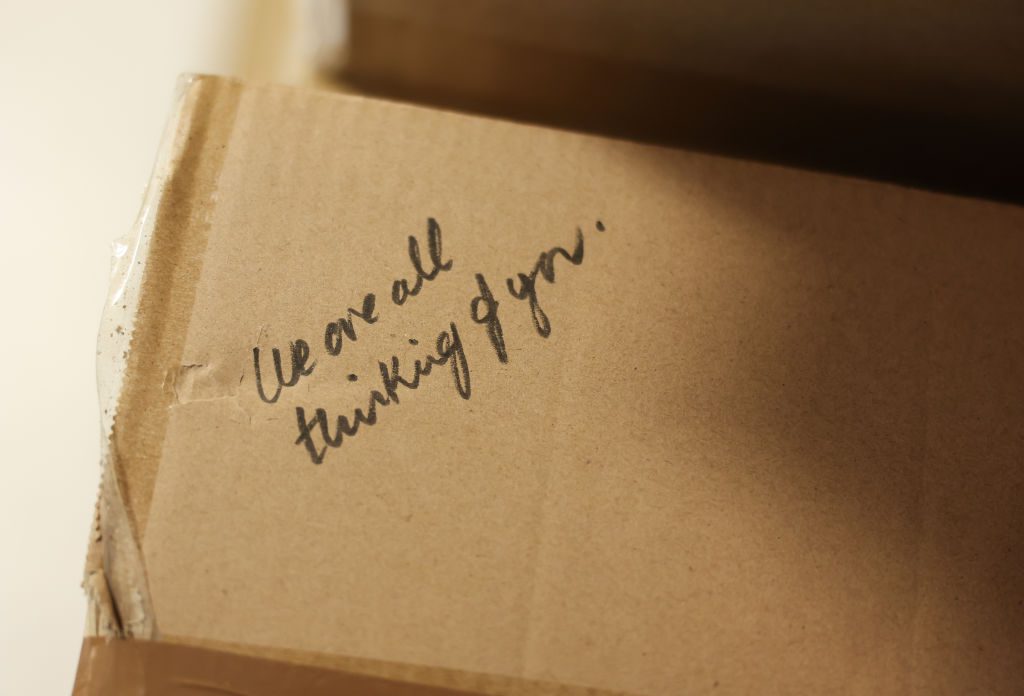

A message of support on a box written by Catherine, Princess of Wales, after she helped pack donations of essential items during her visit to the All Together Community Centre at the Lexicon Shopping Centre on October 4, 2023 in Bracknell, England. Photo: Chris Jackson/Getty Images

By the way, in a survey of Polish citizens conducted for a report by Robert-Myron Staniszewski of the University of Warsaw on the social perception of refugees from Ukraine, the fear of a worsening crime situation is not ranked first among the threats posed by Ukrainians. Among the most pressing concerns is the negative impact on the labour market.

‘There is a problem with crime because of migrants, but it doesn’t concern Ukrainians,’ says Nadia, who has settled in Germany. — ‘In our neighbourhood, there are beggars near the supermarkets — mostly Roma from Romania. It seems to me that I am the only one who is annoyed by them — the locals treat them kindly, although they are all of working age. The Germans say that in the early 2000s it was particularly dangerous on the streets when Italians were in conflict with Serbs.’

‘Ukrainians mostly work,’ Ella Libanova says. — ‘There are very few men among Ukrainian migrants, mostly women and children. Therefore, it is unlikely that they worsen the crime situation so much.’

Vasyl Voskoboinyk, President of the All-Ukrainian Association of International Employment Companies, draws parallels with the United States.

‘We remember America in 1920-30, when the Italian mafia appeared there. But you need to understand that people were leaving a poor country, unable to earn legal money to live at the level they dreamed of, so they formed groups,’ the expert says. — ‘But if 80% of those who have left are women and children, it is unlikely that Ukrainian women will create some kind of women’s mafia of their own.’

Oleksandr Pestrykov notes that there is no specific data on Ukrainian crime in Poland, but previous studies on migrant crime generally show a standard trend: crime among foreigners is lower than among local citizens, if only because they face deportation.

‘The main stereotype attributed to Ukrainians is the tendency to drive drunk,’ an expert from the Ukrainian House Foundation says. — ‘Theft and a tendency to domestic violence are also attributed to them.’

At the same time, Ukrainian women suffer from psychological violence provoked by the stereotype that ‘Ukrainian women are prostitutes.’ After the programme ‘Immigrants for Swedes’ on Swedish television (SVT), in which comedian Elaf Ali joked that Ukrainian women are commonplace in Swedish brothels, a Ukrainian woman in a local club was told by a stranger that she was a prostitute, because ‘they even say that on TV’.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

Myth 5: Refugees increase the burden on the healthcare system, education system and housing market

Experts predict that the painful issues of waiting lists for doctors, which now include many Ukrainians, the burden on the education system and rising housing prices may become the biggest problem and cause a deterioration in the attitude of Europeans towards Ukrainians. After all, Ukrainians will face not only less socially protected locals, but also those whose jobs Ukrainian refugees do not apply for.

‘Poles have a low level of trust in their own state and are aware of the government’s inefficiency when it comes to social services,’ Ada Tymińska, a human rights activist with the Helsinki Human Rights Union in Poland and a researcher of anti-Ukrainian hate speech in Polish social media says. — ‘In Poland, you have to wait in lines to see a doctor for a long time, it is difficult to enrol a child in a kindergarten — it is true. So, the sudden appearance of new people causes a sense of growing threat. However, there were problems with access to specialised medical care even before the arrival of Ukrainians. This only shows that the state is ineffective in some aspects.’

Respondents to Zaborona’s survey also spoke about problems in the medical and educational systems in the countries where most Ukrainian refugees live. For example, one girl said that in Germany, she was offered an appointment with a mammologist after seven months, while another could not find a place in a kindergarten in a Czech city.

‘People are coming, the burden [on the health and education system] is increasing. But there are also more jobs,’ Ella Libanova, Academician of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Director of the Ptoukha Institute for Demography and Social Studies notes. — ‘There are a lot of medical and pedagogical workers among Ukrainian migrants. Who prevents schools with Ukrainian students from hiring Ukrainian teachers? On the one hand, it is employment for Ukrainian women, on the other hand, it is simplified education for children.’

Oleksandr Pestrykov predicts that problems in the education sector will worsen in the autumn of 2024, when all Ukrainian children will be obliged to attend Polish schools. Until now, parents could decide for themselves whether to leave their child in a Ukrainian school on-line. Now, this will mean more children in the classroom, more conflicts, parental disputes, and bullying.

Children sit in a classroom during the first lesson after the opening ceremony of the first Ukrainian school on April 28, 2024 in Bonn, Germany. The idea to create a school with Ukrainian as the language of instruction came from Oleksiy Nazarenko, head of the NGO Ukrainians in Bonn. Photo: Dmytro Bartosh/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

Temporary status gives the right to medical treatment in Poland. ‘But the thing is that if you have to pay for housing and live on something, you have to work,’ Olena says. — ‘And when you work, you have healthcare even without a status, because you pay deductions from your salary. And your turn to see a doctor is legally paid for.’

The Ukrainian House Foundation analysed the data of the medical system for 2022. During the first year of the war, PLN 0.5 billion was spent on Ukrainians, although PLN 2 billion was planned. It turned out that Ukrainian refugees did not use even half of the amount that was planned to be paid for them through the National Health Fund.

‘By 2022, the majority of our citizens in Poland were young childless people who simply did not go to hospitals,’ expert Oleksandr Pestrykov explains. — ‘Meanwhile, there are many mothers, children, the elderly and people who are very health-conscious among refugees. They just start to be seen in hospitals, and it becomes difficult to convince an ordinary Pole that Ukrainians do not pose a threat.’

According to the study ‘Social Perception of Refugees from Ukraine, Migrants and Actions of the Polish and Ukrainian States’ by the University of Warsaw and the Academy of Economics and Humanities in Warsaw, the most common reason for the negative attitude of Poles towards Ukrainian refugees is the alleged ‘dependency position’. For the first time, respondents pointed to ‘Eastern mentality, Soviet culture’, which is marked by a lack of concern for the common good. Many Poles say that Ukrainians have claims to social benefits, believe that everything should be free for them and want to have the same rights as Poles.

‘There was a shortage of doctors and teachers in Poland even before the war, and there are still many vacancies, so they hire Ukrainians,’ Ukrainian Natalia says. — ‘Our people are trained to work well, diligently, responsibly, so in many areas even locals prefer to get services from Ukrainians, especially in the field of beauty, cooking, and repair.’

Oleksandr Pestrykov notes that he has not recorded a single case when a Pole did not get something because it was given to Ukrainians: ‘However, this does not prevent pro-Russian parties from directly stating that the government is now supporting not only its own citizens, but also citizens of the neighbouring country. This stereotype is very common’.

As an argument in favour of the conspiracy theory that locals tend to believe in, he cites a new survey showing that more than 60% of Polish citizens agree with the statement that Poles in Poland are now becoming ‘second-class citizens’ and Ukrainians have received privileges that are not theirs.

A march of refugees and locals to mark the second anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Porto, Portugal, 24 February 2024. Photo: David Oliveira/NurPhoto via Getty Images

‘The situation with housing is more complicated,’ Oleksandr Pestrykov explains. — ‘In 2022, prices really started to rise, and, for example, in Warsaw, housing available for students almost disappeared. This was indeed due to the influx of Ukrainians, but now prices have almost returned to the level of 2021.’

Viktor, who has settled in the Czech Republic, admits that the arrival of Ukrainians has affected the real estate market: ‘But the apartments are rented out by locals. Therefore, it is money for the locals that they can use for their living or to improve the condition of their homes. Stereotypes about Ukrainians are spread mainly by people who are not very educated, including right-wing radicals.’

Other stereotypes faced by Ukrainian citizens abroad include that if you are fleeing the war, you have nothing and will have nothing.

‘In the eyes of foreigners, we [Ukrainians] must look like literally homeless people who have no money for bread,’ says a young woman in Zaborona’s survey. — ‘Very often foreigners forget that before the war we were successful in our business. So having a car is normal. Having a dress or jeans is also normal. So is taking care of your hair and body.’

Some foreigners are surprised that Ukrainians have very good education and qualifications. ‘We have to explain that we fled not from poverty, but from war. The second is language skills. Some people don’t understand how we know 3-4 languages at once, and very often they are surprised and say something like ‘wow, what a great English, where did you learn it?’,’ says another participant in Zaborona’s research.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

Misunderstandings between Ukrainians and returning

On the other hand, Ukrainians who have decided to stay outside the country share the experience that they are considered cowards and traitors in their homeland who do not care about the fate of the state. As if they are living their best life abroad, have forgotten about Ukraine and do not care about the war. That they didn’t really leave for security reasons, but for more money. That they do not donate or help.

The Centre for Economic Strategy estimates that between 860,000 and 2.7 million Ukrainians may remain abroad. These are mostly promising, educated Ukrainians, students, mothers with children, who will be joined later by their husbands. Older people or those with lower levels of education are more likely to return to Ukraine after the war.

According to the CES, the non-return of Ukrainians will have a significant impact on the Ukrainian economy, which could lose between 2.55 and 7.71% of GDP.

‘If half of those who left stay abroad, it will be a very serious blow to us,’ Academician of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Director of the Ptoukha Institute for Demography and Social Studies considers. — ‘The issue of returning Ukrainians who left abroad because of the war will be one of the most important challenges in the near future.’

Ukrainian children point excitedly to their hometowns at a board with a map of Ukraine during the Light for Ukraine ceremony, which brought together refugees and locals to pray for peace. February 23, 2023, Grabie, Gmina Wieliczka, Poland. Photo: Artur Vidak/NurPhoto via Getty Images

The general sentiment is confirmed by the data of the OneUA international survey, which covered more than 18,000 respondents in eight European countries. Ukrainian refugees living in Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Moldova and Romania are more likely to indicate that they intend to return to Ukraine than refugees in the Netherlands and Germany. The main factors are the motives of social attachment and the economic factor (Return intentions among Ukrainian refugees in Europe: A Cross-National Study, published on July 22, 2024).

In the Zaborona survey, only 11% of respondents say they are changing their minds (whether to stay or return). Among the obstacles to return are the ongoing war and the unpredictability of the future. Recipients who will stay in Ukraine explain their choice by the lack of opportunity to leave and their love for the country. It is important to note that those who chose to live abroad, in addition to a sense of security, also cite love for Ukraine as an argument — being safe, they have the opportunity to donate and promote Ukrainian interests in other countries.