At 30, I had my first cancer scare. Due to the fact that I possess a rare genetic mutation which makes me more vulnerable than the average person to several different kinds of cancer, it is possibly not the last cancer scare I’ll face. The journey from discovering that there might be a serious problem with my health to ruling out the unthinkable was long, arduous, and, most importantly, expensive. On top of that, I had to navigate the rules (both spoken and unspoken) of the Ukrainian healthcare system as an American – and in the middle of a global pandemic, no less. What I learned was that it doesn’t matter if you live in America or Ukraine — both countries are ill-equipped to provide cancer patients with access to substantive medical care.

In the autumn of 2020, I was suffering from constant stomach pain. I made an appointment with my doctor, who in turn gave me a referral to see a gastroenterologist. At the time I was amazed by how effortless the whole process seemed, and thankful that as a foreigner living and working legally in Ukraine, I had full access to the privileges of the healthcare system even though I was only a temporary resident. The gastroenterologist listened to my symptoms and recommended that I have both an endoscopy and colonoscopy done. The shopping list of supplies I was asked to purchase beforehand by the anesthesiologist and endoscopist — gloves, paper towels, a catheter, and so on — was something new and strange for me, but otherwise, I went into the appointment feeling pretty calm.

Everything changed when I woke up from the procedure. The anesthesiologist, who had been joking with me until I went under, loomed over me with a serious look on his face and said they had discovered a problem during my colonoscopy. Later on, the endoscopist would tell me that in the thousands of times he had done this procedure, he had never encountered a situation like mine: there were polyps everywhere, literally everywhere. The video of it made me so nauseous that I almost threw up in the sink. After showing me the video, he told me that I had to pay 500 hryvnias (approx. $18) for the procedure. I was pretty sure he was just trying to take advantage of me, and that being registered in the healthcare system meant that the colonoscopy shouldn’t have cost me anything, but I was too upset to care. I gave him the money and took a taxi home. A few days later, the gastroenterologist’s hands trembled as she read the paper with the results written on them. She confessed that she didn’t know how to help me, and that in fact, it was too late for her to help me: I needed to meet with a surgeon. The biopsy taken during the colonoscopy had come back negative, but it didn’t matter. There was no treatment that she knew of which could remove that many polyps — and not all of them would remain benign forever. Later on, I looked at the small piece of paper with my biopsy results: there were only a few handwritten sentences that included vague, ominous-sounding phrases like “dense infiltration of lymphocytes”. I had no idea what any of it meant and how anyone could discern that I was cancer-free.

Kate Tsurkan

I called a surgeon that the gastroenterologist was kind enough to recommend and met with him at a private clinic in Chernivtsi. After watching the video of my colonoscopy, he told me that I could have a colectomy — a surgical procedure to remove my colon — done right away if I wanted to, but because I was still young and wanted to have children (the scarring caused by a colectomy can negatively affect fertility) he recommended that we first try to treat these polyps as if they were caused by an infection and see, after another colonoscopy in three months’ time, if they would disappear. I felt more at ease after listening to him: it seemed like surgery was not the only option. He asked me to meet with the gastroenterologist who worked in that same private clinic, and they both promised that they would do their best to help me. These two separate consultations – which did not differ much in content – cost me 1,000 hryvnias altogether (approx. $36). I would then spend nearly 2,000 hryvnias (approx. $72) more that day on a variety of blood tests and stool samples.

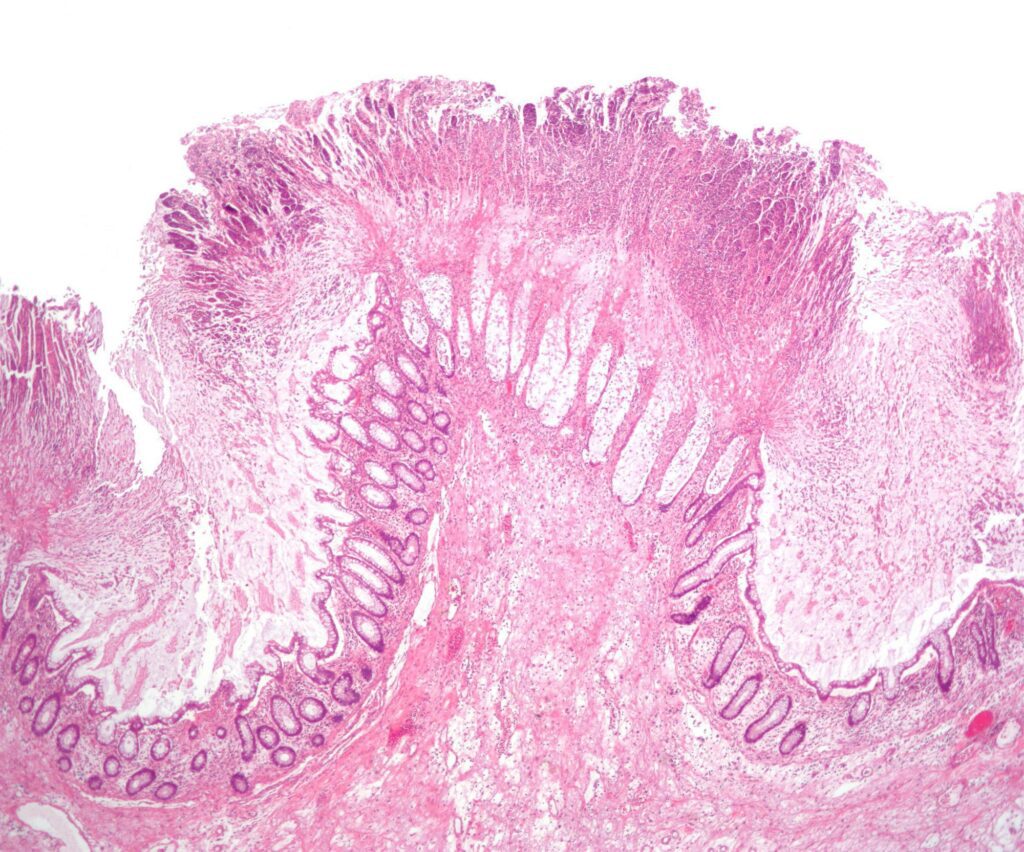

For the next three months, I adhered to a very strict diet — porridge without milk, baked potatoes, boiled vegetables. When your choice of nourishment is so limited, it is easy to start thinking of food as your enemy. I had to constantly remind myself that it was only temporary and if I took all of the pills the gastroenterologist had prescribed me (which cost a little more than 1,000 hryvnias) my nightmare would be over. In the winter of 2021, I returned to the private clinic for my second colonoscopy, which needless to say, cost more than 500 hryvnias. And the polyps were still there. The surgeon met me in his office after the procedure and told me, rather somberly, that I had to go to Kyiv. He mentioned some private hospital run by Israelis and that it would be expensive, very expensive, but that it would be my best option if I didn’t want to go back to America. There was nothing else I could do: surgery was inevitable.

I returned home and cried until there were no more tears left. I searched for videos on YouTube of people who had had a colectomy, trying to understand the future that awaited me. It was particularly enlightening to watch one American video blogger who was not afraid to discuss anything when it came to her life with an ostomy bag. She had made all kinds of videos, from showing how to clean her stoma to discussing the challenges of having sex. I was thankful for her sincerity and her constant assurances that despite the occasional setbacks, it was totally possible to live a normal life with an ostomy bag.

Micrograph of pseudomembranous colitis, an indication for colectomy. Photo: Wikimedia

That spring, I didn’t want to go to the private hospital in Kyiv that the Chernivtsi surgeon had recommended. I was bitter and resentful that I had let myself get my hopes up and spent all that money for what felt like nothing. I recalled that I was friends with a woman on Facebook who worked in the Ministry of Health. Feeling like I had nothing to lose, I wrote her a message along the lines of “Hi, I know we don’t know each other, but…” explaining my situation and asking her for advice. She told me that my best option was to go to the Cancer Institute in Kyiv and to meet with a doctor who specialized in the treatment of colorectal cancers. There were no empty promises from the doctor at the Cancer Institute, only facts — and for that, I was thankful. The biopsies which had been taken during my previous two colonoscopies in Chernivtsi did not provide sufficient information about my condition. If I wanted to have a child in the next year or two, then I needed to definitively rule out cancer first: there was no choice but to have a third colonoscopy done. We would discuss the prospect of surgery only after the results of a genetic test searching for mutations — like familial adenomatous polyposis — which would have meant that a total colectomy was truly inevitable (the life expectancy of patients with untreated familial adenomatous polyposis is 42). Everything had to be done in the correct order, without rushing on to the next thing, one step at a time.

I was sent to a private clinic in Kyiv that specializes in gastroenterological disorders. My third colonoscopy cost more than 5,000 hryvnias (approx. $180), but at least that endoscopist did not speak in superlatives. Two weeks later, the results of the biopsy confirmed that none of the polyps were cancerous. It struck me how much longer it took for the results of that biopsy to come back, compared to the 2-3 days it had taken each time in Chernivtsi. I then waited nearly two months for the results of a genetic test to come back as well, in order to rule out mutations like familial adenomatous polyposis. The genetic test cost more than 13,000 hryvnias (approx. $470).

The most important thing is that I don’t have cancer, and it looks like a colectomy is not in my immediate future. I don’t have familial adenomatous polyposis, but because of the genetic test, I learned that I have Cowden Syndrome, which makes me more vulnerable to several different types of cancer. Now I have to start paying extra attention to the health of my thyroid and breasts, too.

Photo: Ante Samarzija / Unsplash

The American healthcare system might be filled with more experts who are better equipped to treat patients with rare genetic mutations like mine, but the cost of health insurance is so high that a cancer diagnosis in America feels like a death sentence (the countless fundraisers for cancer patients on websites like GoFundMe only heightens the feeling of dread). Nearly 1 in 3 Americans avoid going to the doctor altogether because of the associated costs, which means that treatable health conditions often risk becoming financially and medically unstable. The American Cancer Society reported that in 2018, American cancer patients paid a total of $8.6 billion out of pocket for cancer treatment and that this financial hardship is only expected to increase in the next few decades – especially for people of color, young people, and those with less education or lower income than the rest of the general population.

According to the World Health Organization 162,595 Ukrainians were diagnosed with cancer in 2020, and of those cases, 84,194 of them died — that’s more than half. How is it that such a low number of patients were diagnosed with cancer in Ukraine last year and yet the mortality rate among them is so high? In Ukraine, the public healthcare system allows patients greater access to medical tests that can lead to early detection and treatment, but outside of Kyiv and other major cities, both state-run and private clinics lack specialists with the knowledge to provide Ukrainians the quality preventive care they deserve. (There was an article about this very issue published by Zaborona in December of 2020.) That is not to say good doctors don’t exist in other regions of Ukraine: it just takes some time to find the ones who can help you, usually by opening up to people and asking around.

The sad truth is that the majority of Ukrainians don’t make the kind of money where they can afford to travel to Kyiv for a few days, receive proper attention in a private medical clinic, and get clear answers about their health. Private clinics like the one I went to in Kyiv might compensate for what public medical institutions lack in terms of the latest diagnostic equipment, but they remain financially inaccessible to much of the population.

Something about these systems has to change: both Ukrainians and Americans deserve better.