“When Asked If There Are Mines Here, He Said: “Percentage 80/20 — Every Fifth Step Is Dangerous.” Diary of a Military Photographer

August 19, 2022

The photographer Vlad Krasnoshchok went with the Armed Forces of Ukraine to collect the trophy equipment of the Russian army, saw the positions from which the occupiers shelled the city infrastructure, walked through mined cities, and continues to document the chronicle of the destruction of Kharkiv. Zaborona publishes Krasnoshchok’s photo diary.

About the author: Vlad Krasnoshchok is an artist from Kharkiv who works with photography, a member of the band “Shylo.” Since the first days of the war, Vlad has been documenting his native Kharkiv, traveling with volunteers to Lysychansk and other cities of Donbas. Photographs for the museum of the Kharkiv School of Photography.

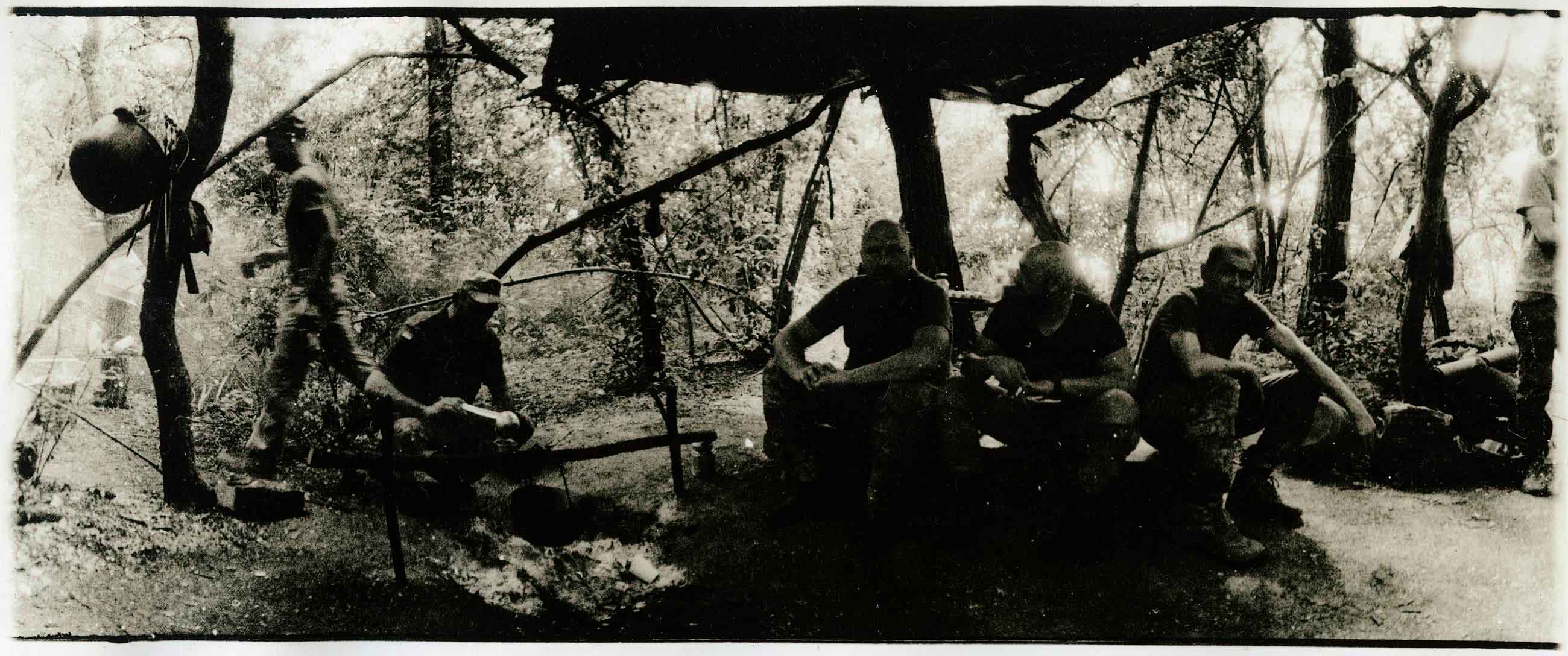

There were two Sashko, Vadim, Mykola Mykolayovych, and a guy with a Bulgarian woman in the car. Similarly, I was sitting somewhere nearby, holding lots of cameras. I was asked to shoot for the Kharkiv Defense Museum. We were driving across the district road to the same broken-down convoy, which included, among other things, fried OMON policemen who were going to “free” us.

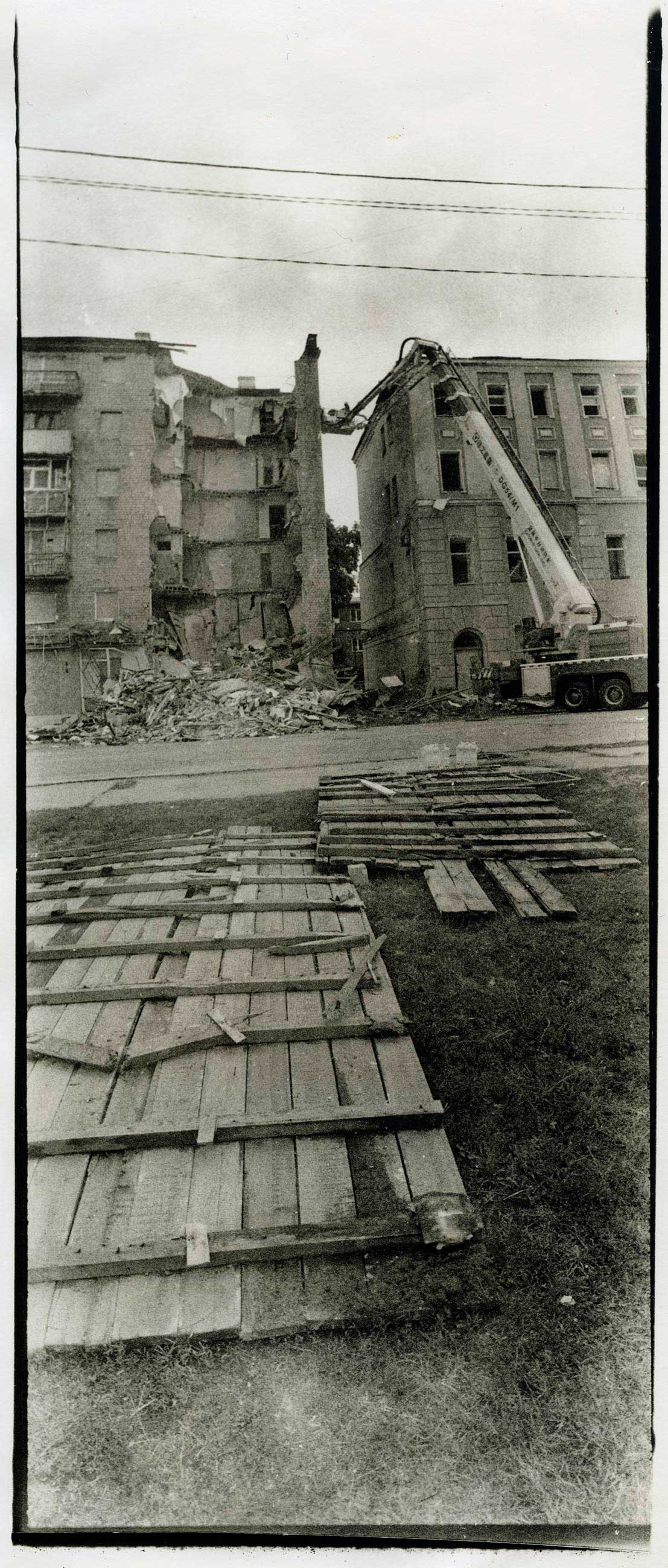

Driving to the district office, the guy with the Bulgarian woman asked for a sedative pill. During the war, he did not go far from home, and the places we approached were regularly shelled by the fucking “Grad.” Having arrived at the place, I took a little digital picture for the benefit of the motherland and, in parallel, took a little bit of black and white film for the motherland and myself. Kharkiv “octopuses” (Kraken unit) approached us to dismantle the surviving “cans” (broken orcs’ equipment). The guy with the Bulgarian started cutting some kind of cannon and calmed down a bit, while we, two Sashko and Vadim, went to examine the wounded and killed “Tigers” and other fried scrap metal.

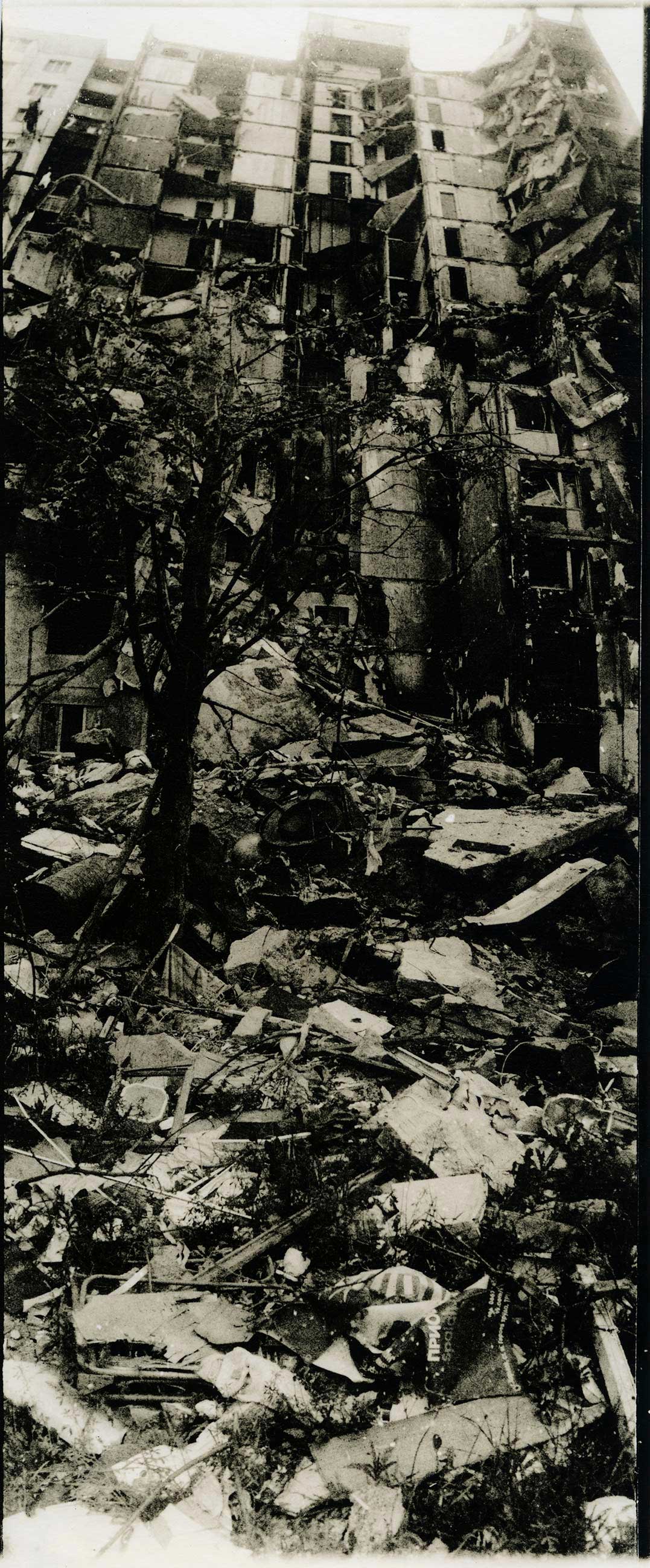

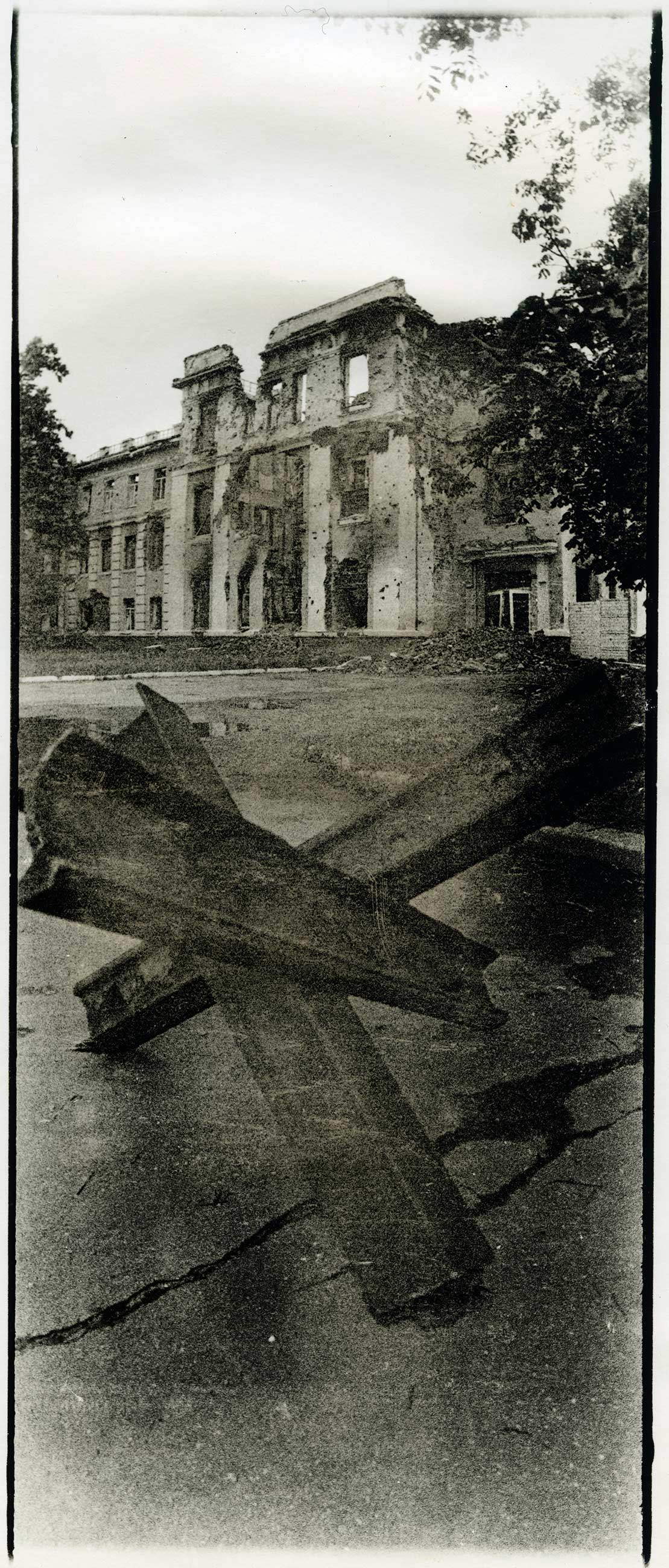

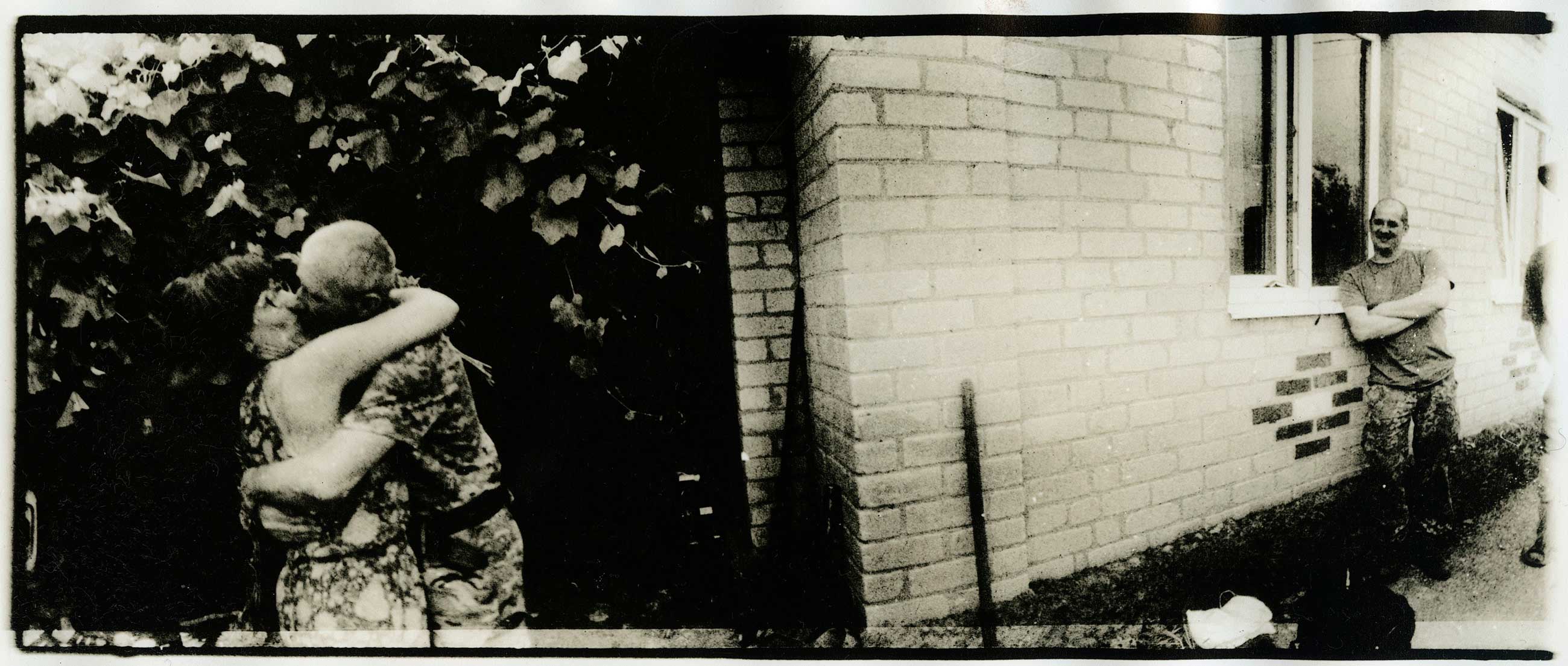

The guys were fun, with a sense of humor. Commander Sasha with an open smile, like Gagarin, Sasha and Vadim are brothers, also cheerful and cool guys. Mykola Mykolayovych managed the process of sawing off artifacts. When we did everything, the fucking hailstones started flying, and the guy with the Bulgarian girl turned pale again. The military guys turned on the Stebalov mode and mocked us until we arrived in Kharkiv and unloaded the good cut from the “cans.” Then there was a trip to the “pidarposadka” (a forest plantation in the area of Malaya Rogani, where the orks’ equipment was stationed), from where the bastards fired at the Horizon, the Chuguyiv highway, the KhTZ area, and wherever the map lays.

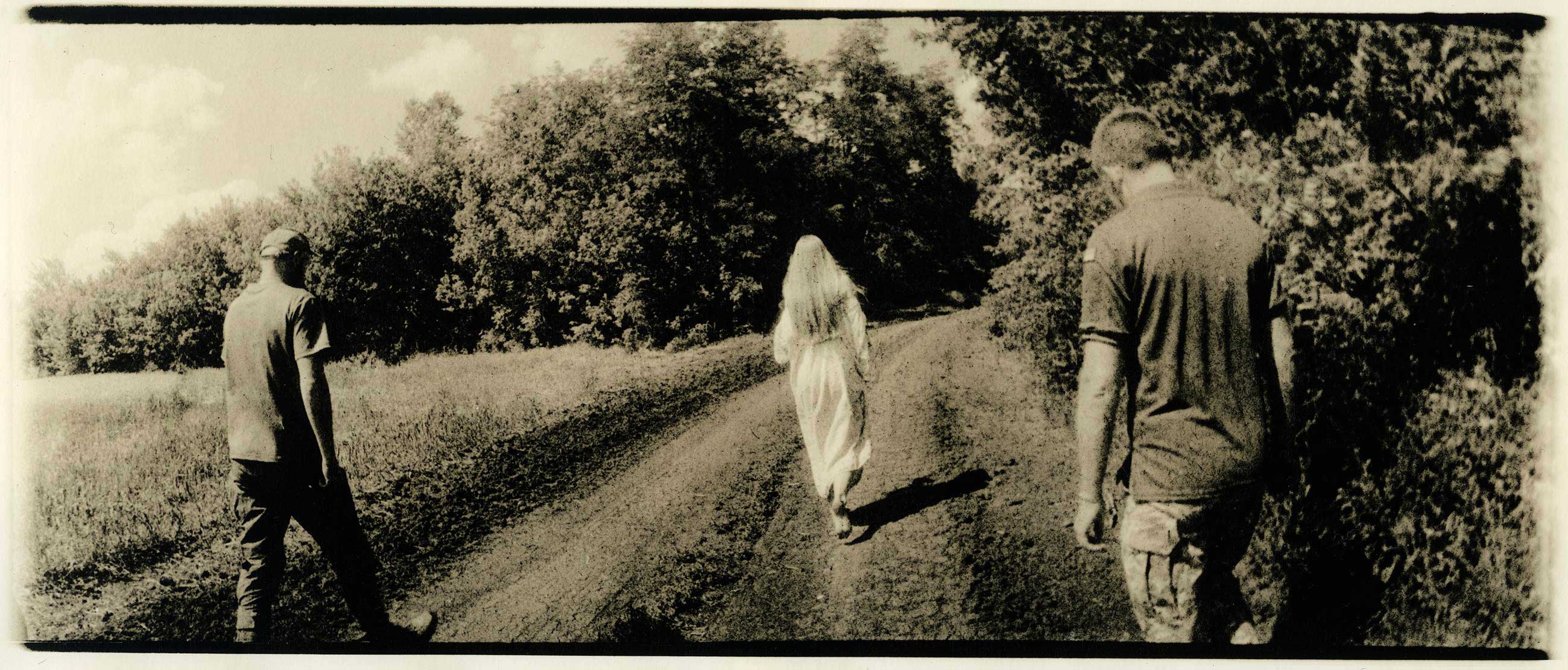

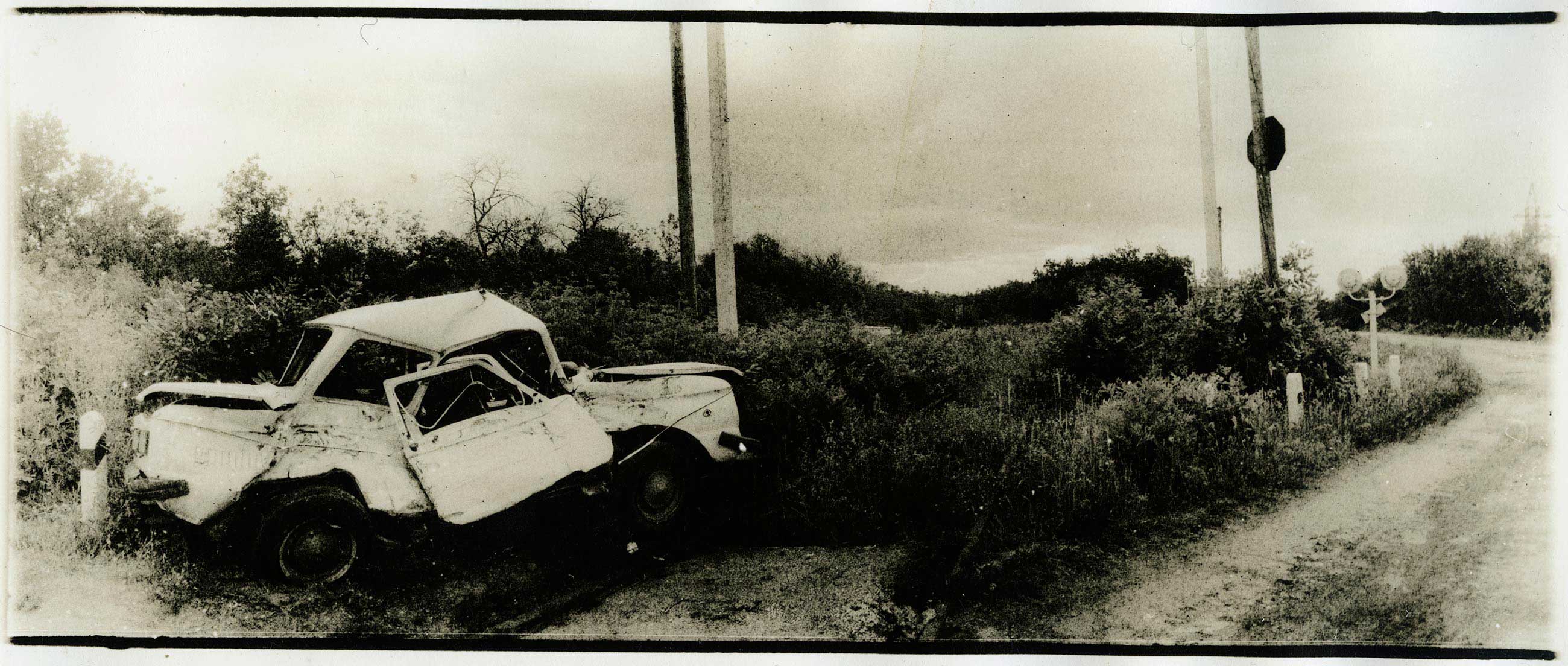

Two Sashas, two best friends, walked ahead confidently, I followed them and buzzed my horizon. When asked if there were mines here, Sashko, the commander with an open smile, said that the percentage was 80/20. That meant every fifth step was dangerous, but no one was afraid. This is how I met and became friends with the defenders of Kharkiv and our country. Later, I traveled with volunteers to Donbas and managed to visit Lysychansk, Severodonetsk, Privila, Sloviansk, Bakhmut, Avdiivtka, and other hot spots. The Bakhmut — Lysychansk road was a zigzag of embankments, on the sides of which lay the corpses of civilian vehicles. The fields around were dotted with round black spots, like the ceilings in the porches of our nine-story buildings, from which a burnt match sticks out.

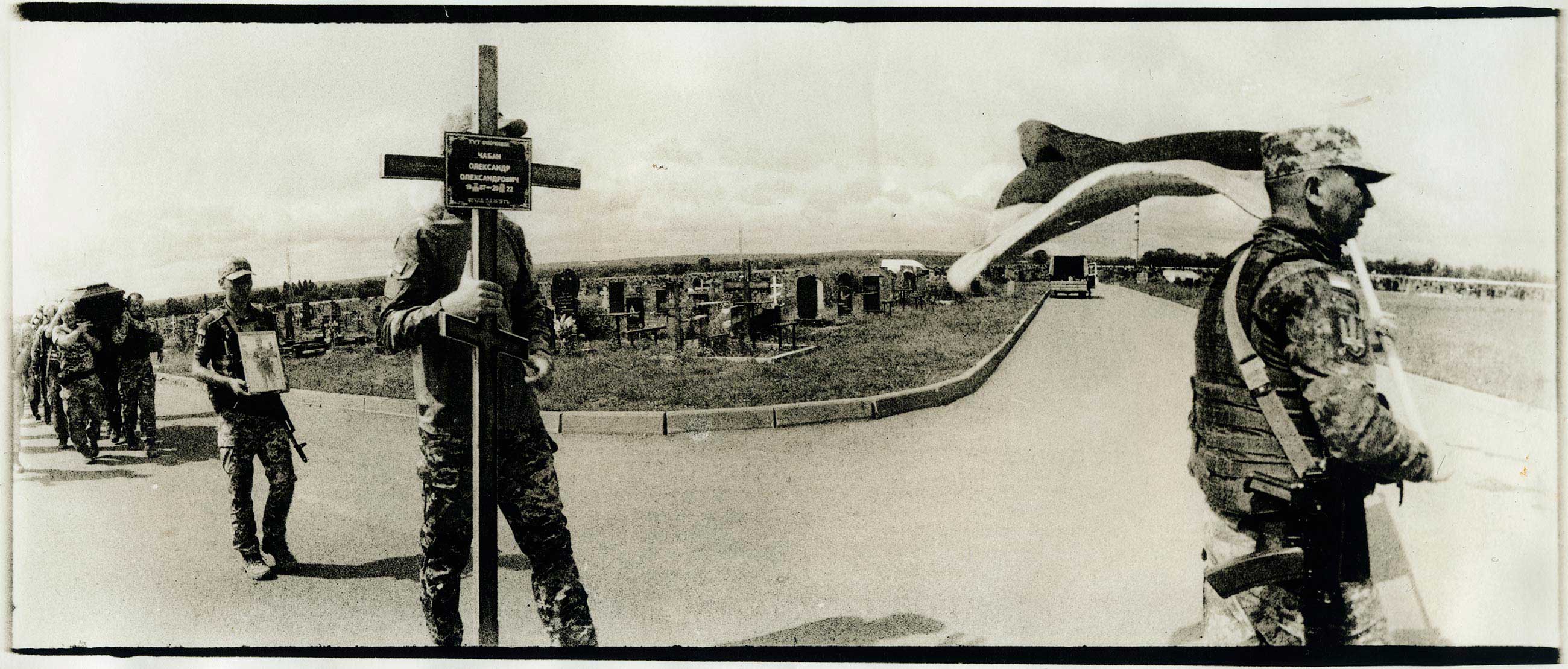

Two months have passed. Sashko celebrated his thirtieth wedding anniversary, and the other Sashko, as always with a smile, told how he taught the young soldier the decorations of war. Some time passed, and I was standing on the Alley of Glory of the famous Kharkiv cemetery. The guys carrying the varnished coffin out of the car approached me and said: “Vlad, start, let’s work.” In the coffin was the same commander with an open smile, Sashko, who gave his life in the battle near Kharkiv — the only casualty of that day. The end.