On December 18, 2022, a museum of the Hutsul artist Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit was opened in the village of Kryvorivnia, the Ivano-Frankivsk region. She has been compared to the American photographer Vivian Maier, who was interested in a comet about to collide with Earth, traveled through India without ever leaving her home village, and painted icons on linoleum and hospital sheets. Pavlo Bishko, the editor of Zaborona, went to Kryvorivnia, visited the museum, climbed the mountains with the Hutsuls, and watched how the villagers called to the empty hut of Plytka-Horytsvit.

Hutsulsky Homer, Ukrainian Vivian Maier

At a wooden table in the corner of the room, 70-year-old Lyudmila, an employee of the Kyiv Institute of Geology, is holding a bag. With her other hand, she manages to flip through the exhibition catalog very slowly. The name is “Overcoming Gravity” — a study of the biography and creative legacy of perhaps the most famous artist from the Ivano-Frankivsk region today.

Lyudmila spent her vacation for the first time in Kryvorivnia, a Hutsul village that was one of the most popular vacation spots for intellectuals at the beginning of the 20th century. Ivan Franko, Lesya Ukrainka, and Mykhailo Kotsiubynskyi spent their holidays here, and Serhiy Paradzhanov filmed the cult film “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors.” She heard about the artist Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit for the first time after accidentally entering a newly created museum dedicated to her work. Lyudmila says: “Now I read how Paraska was in exile. And the fact that she was not like everyone else attracted rather than repelled.”

Map: Kateryna Kruglyk / Zaborona

Plytka-Horytsvit became famous thanks to photography. Found in her hut in 2015 and already digitized, the photo archive includes more than 4,000 photos. A part of the archive called “The Sun of the Mountains” was presented at the Odesa Photo Days photography festival in 2018 and 2019 at the large-scale exhibition “Overcoming Gravity” at the Art Arsenal. She was already nicknamed the Ukrainian Vivian Mayer (an American photographer who worked as a nanny for more than 40 years and secretly engaged in street photography — her archive was found after her death); and Homer of the Hutsul region, this time for literary works.

The building of the newly created museum of Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit in Kryvorivnia. Earlier, the village council was located here. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Kryvorivnia as inner India

The new museum of Plytka-Horytsvit is a two-story building in the center of the village with a four-pitched hipped roof and triangular windows, typical elements of Hutsul architecture. Hills and the winding shore of Chorny Cheremosh surround the building. The museum was supposed to open on March 1, the 95th anniversary of Plytka-Horytsvit, but due to the full-scale war, the opening took place in December 2022. The initiators of the museumification of the heritage of Plytka-Horytsvit were the Rybaruk family: priest Father Ivan, his wife Oksana, and son Pavlo.

Visitors in the biographical hall of the Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit museum. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

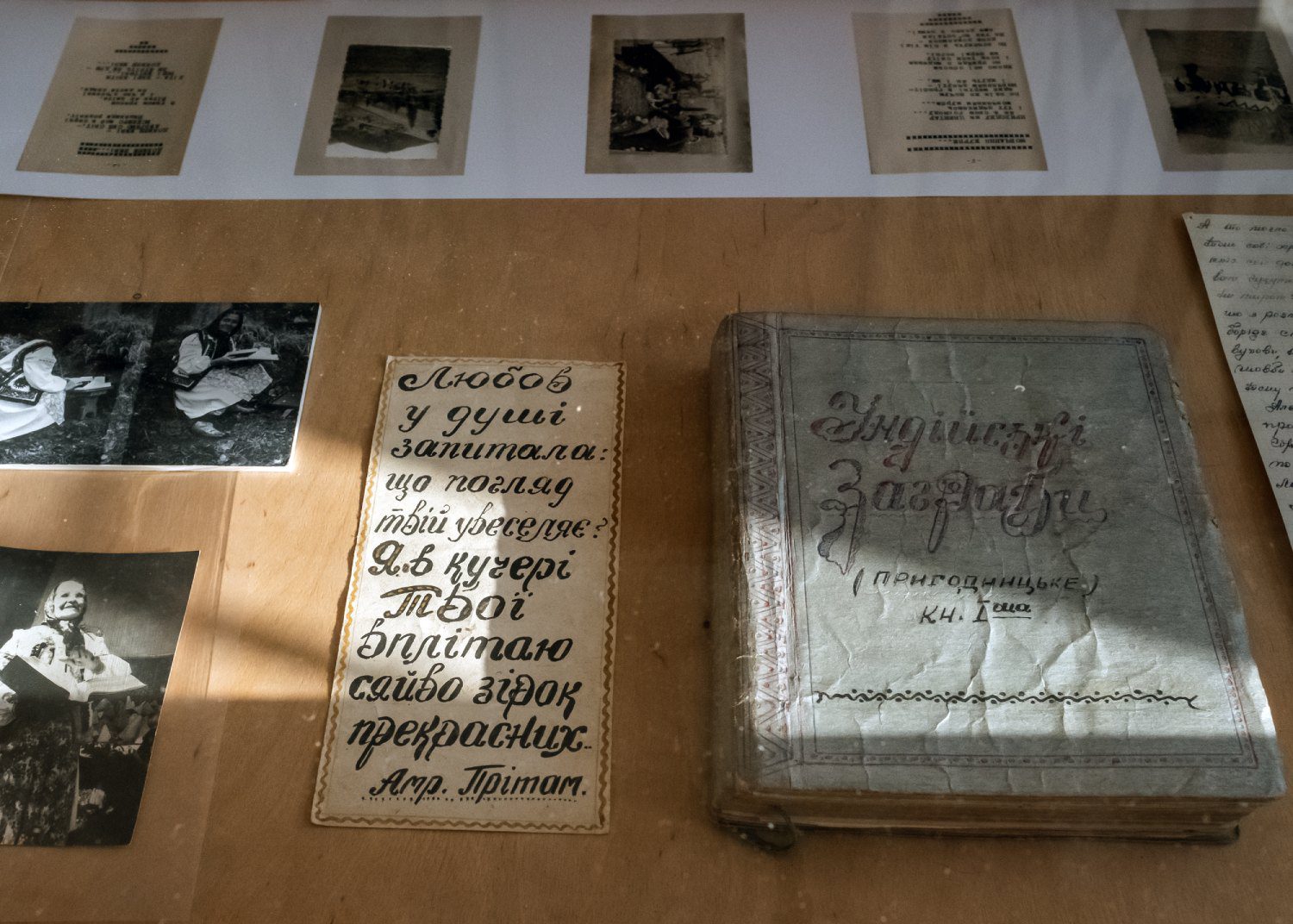

Museum exhibits, including one of the volumes of Paraska’s adventure novel “Indian charms” about the travels of two Hutsuls to India. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

“From the age of eight, my wife Oksana went to Paraska at least 2-3 times a week. It was called “taking the bread to Paraska,” Father Ivan says in her family. “When I first met my future wife, she took me to Paraska instead of her home.”

The museum consists of three halls. In the first, biographical, there are family photos, personal belongings, and documents of Paraska. Among them is the questionnaire of the arrested nonpartisan Plytka-Horytsvit — an archival document of the Ministry of State Security in the Stanislav region in 1945. Then, with the help of the UPA, 17-year-old Paraska went into exile in Kazakhstan, from where she returned to Kryvorivnia after 10 years. The set of personal belongings seems somewhat strange: a mousetrap decorated with patterns and a thin sheet of silver metal, Paraska’s tombstone, is laid out behind the display case. She chose the epitaph: “God rest the Servant of God Paraskeva Karpatska-Plytka-Horytsvit.”

Visitors get acquainted with the exhibits of the newly created Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit museum. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

“A woman figure occupies a huge place in Paraska’s work,” says Father Ivan Rybaruk, rector of the Church of the Nativity of the Most Holy Theotokos and one of the initiators of the creation of the museum. “In the first place are Lesya Ukrainka, Princess Olga, and Indira Gandhi. In the museum, you can see portraits of Mahatma and Indira Gandhi by her.”

After being exiled to Kazakhstan, Paraska spent the rest of her life without leaving Kryvorivnia. But it may seem that she has been to India — or instead, she has been painstakingly building an image of inner India for years, to which she traveled through news from newspapers. In the 1950s, during a cooperation between the USSR and the newly independent India, Paraska collected newspaper clippings with info about this country and photos of Indian figures.

In the second hall of the museum are icons, illustrations, sculptures of animals, and books by the author. Among them is the first volume of the book “Indian Charms” — a series of six-volume adventure novels by the artist about the travels of two Hutsuls to India. For this novel, Paraska created an illustrated series, “Adventures in the Indian Jungle,” which occupies an entire wall in the hall. In one of the plots, Hutsuls fly on elephants: “And a journey in the wilderness!? Let’s fly on trunks… After all, these elephants are very nice jokers!” says the text accompanying the illustration.

Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

In 2009, at the first exhibition of Paraska’s work at the Mykhailo Hrushevsky Museum in Kyiv, the curators placed several of her books in a cradle. Plytka-Horytsvit had no children; she called her “children” books — written and illustrated — that numbered more than 500 copies.

Plytka-Horytsvit, among other things, was engaged in icon painting: she created over 100 icons but managed to save 82. Among them is the icon of St. Archangel Michael. Its peculiarity is that it is written on linoleum. “He was brought from the hospital by Paraska’s neighbor, who worked as a nurse,” Father Ivan says. “The torn linoleum was lying in the hospital kitchen, a surviving piece was cut out of it, and Paraska wrote an icon on it.” Other icons nearby are drawn on a hospital sheet.

Icon of Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit in the Kryvorivnia church. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Another 10 icons are in the Kryvorivnia temple, which can also, in a certain way, be considered a museum of Plytka-Horytsvit. In 1972, the priest Father Mykola ordered to remove her icons from the church; in his opinion, they were not canonical. “Icons are written according to a certain canon, that is, a rule,” Father Rybaruk says. “For example, this is a reverse perspective, a suitable background. I can’t say that Paraska didn’t have this. She wrote with her soul, in her own way — and that’s why she wrote well. Paraska did not follow the rules of color or composition, but for me, her icons are alive.” Later, with the arrival of a new abbot, the icons of Paraska were returned to the church, where they still are.

In the photo hall of Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

The third, smallest hall is dedicated to photography: portraits with photo stands-in — stands for photography with special holes for faces. Paraska often used photo stands-in and decorated them with the words “Hello from Kryvorivnia!” integrated into the ornament. or “Hello from the Carpathians!” Ukrainian Vivian Mayer, Paraska portrayed the traditions and rituals of the Hutsul region residents — secret, street, or rather rural photo-documentary. Her photos show the formation, growth, and withering of a generation of Kryvorivnia peasants in the 1960s–1980s. On the stand, next to self-designed photo albums and a photo cutter, Paraska’s cameras are displayed in a neat row — Soviet models “Lomo,” “Smena,” and “Chaika.”

“Do you know why they cling so much to “Paraska, the photographer”? The world has become very visual,” Father Rybaruk says. “Earlier, in normal times, 50% was visuality, another 30% to hearing and other things. And now more than 90% is visuality. No one hears anything, only looks.”

A sign pointing to the house-museum of Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit in Kryvorivnia. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Is Comet Kogouteka visible over the mountains?

The road from the museum to Paraska’s house, which she built with her father in the 1950s after returning from exile, passes a carefully restored Hutsul church. Paraska’s hut is in the village of Kryvorivnia Grasparivka at an altitude of 700 meters above sea level. Ivan Shkriblyak, a village resident, is heading towards her on the road. Dressed in a vyshyvanka, a wide leather belt with several buckles, a sleeveless fur coat-keptar, and a cap-horn, Ivan gains height, holding in his hand a bartack — a Hutsul ax. Shkriblyak is 50 years old, and he was born in Kazakhstan when his parents were in exile there, as were Plytka-Horytsvit and many other residents of the Ivano-Frankivsk region. He points to Bartko: you go there.

A fragment of the Church of the Nativity of the Holy Virgin in Kryvorivnia, which is more than 350 years old. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Residents of Kryvorivnia wait in the church yard for the start of the daily Divine Service. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Kryvorivnia resident Ivan Shkryblyak on the street leading to the Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit hut. Kryvorivnia, December 2022. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Monument to Oleksa Dovbush in Kryvorivnia. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

At the 15th minute of strenuous walking, a hut appears from under the forest. Today, a faint path leads to it from the main road, and in the 1960s and 1970s, it was well-trodden. Students regularly visited Paraska during ethnographic expeditions to the Carpathians, which were very popular at Ivano-Frankivsk and Lviv universities. Khatinka is a different point of the Kryvorivnia guidebook, which the teachers of the ethnographic faculties marked. Paraska read and sang Hutsul legends to the student guests, which she collected and wrote down, and was often their guide on mountain hikes.

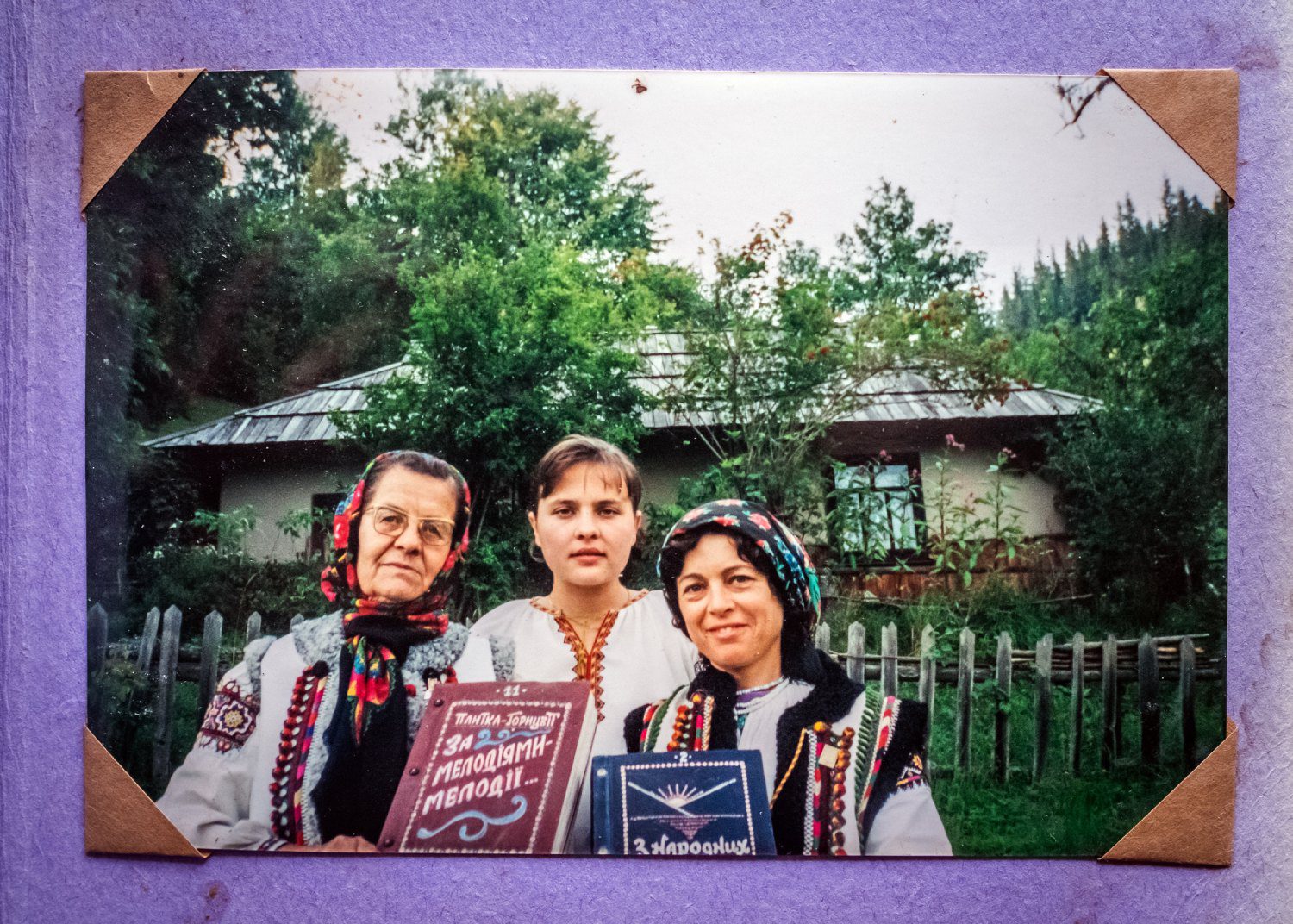

Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit (left) and Oksana Rybaruk together with a fellow villager hold Paraska’s books, against the background of her house in Kryvorivnia. From the photo album of Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

All the hut windows are covered with a special film that protects the paper illustrations from harmful infrared radiation — it was made and sent a few years ago by a man from the USA who learned about the museum’s creation. There is a part of the artist’s heritage in two rooms and a corridor of the house, which has not yet been exhibited anywhere. The floor of the rooms is decorated with beds — traditional Hutsul carpets made of sheep’s wool. In the closet painted by Paraska, her needlework books are sorted by topic. Among them are chants, songs, and poems about mountains.

The Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit hut, where the literary and memorial museum has been located since 2005. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Pavlo Rybaruk is the director of the Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit museum in Kryvorivnia. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

On the windowsill of one of the rooms, you can see small, signed fragments of wood. It is neatly written on a piece of paper glued to a conifer: “A piece of a summer fir under which I rest while going to the mountains.” “And Paraska also collected triangular stones that reminded her of the Trinity: God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit,” Father Ivan says. “There were a huge number of these triangles under the wall of her house.”

The interior of the hut-museum of Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Among other things, there is a large stack of several dozen letters. “Paraska received a large paper bag of letters a week,” Father Ivan Rybaruk says. “She had more correspondence than the entire village combined.” An epistolary with deported Hutsuls in Kazakhstan, about 60 correspondences with mobilized soldiers, and somehow separately, attracting attention — a letter to the observatory in Odesa, in which Paraska asks about the fate of Comet Kogouteka, which, according to forecasts, was supposed to collide with the Earth in the 1970s.

Vytinanky by Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Sorted books of Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit in the hut-museum. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

Koliada for Paraska

“In 1995, Paraska was buried on the Saturday before Easter,” Father Ivan recalls. “Due to holiday preparations, very few people came to her funeral. However, at this time, a team of Polish television arrived in Kryvorivnia to film Easter. The camera crew happened to document Paraska’s funeral. It was a funeral that, for the most part, the native village did not see, but the whole of Europe saw.” It is a quote from Oleg Drach’s film “Koliada for Paraska” — however, it does not describe today’s state of affairs.

Portrait of Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit in the museum hut. Photo: Pavlo Bishko / Zaborona

On a dark, cold evening, a group of carolers in traditional Hutsul clothing arrived near the Paraska museum. Among them, you can see Ivan Shkriblyak, who was walking up the road to Paraska this morning. He carols in the group of 80-year-old Ivan Zelenchuk, who has been keeping the tradition of Christmas caroling for 30 years. Upon arrival, a party of carolers announces their arrival at the empty house of Paraska with the synchronized sound of trembits. In the dark, they sing ples, a unique Hutsul Christmas rite, and lightly throw up their turbans as if reflecting the rhythm of the melody.