The life of small Transcarpathian villages could remain known only to its inhabitants if it were not for the ordinary turner Mykhailo Kosyuk. For more than 20 years, he photographed descendants of Austrian and German foresters, went to the woods to shave loggers to make a decent photo portrait of them, and documented natural disasters in his native village. Thousands of pictures, which formed a historical document of the mountain settlement, as well as a report on the forestry of the Ukrainian Carpathians, were burned in a fire — only two photo albums remained. Due to the severe health condition of Mykhailo, Zaborona was able to talk only with his wife Mariya — she told what these photos of a missing life, which no one can see anymore, were like.

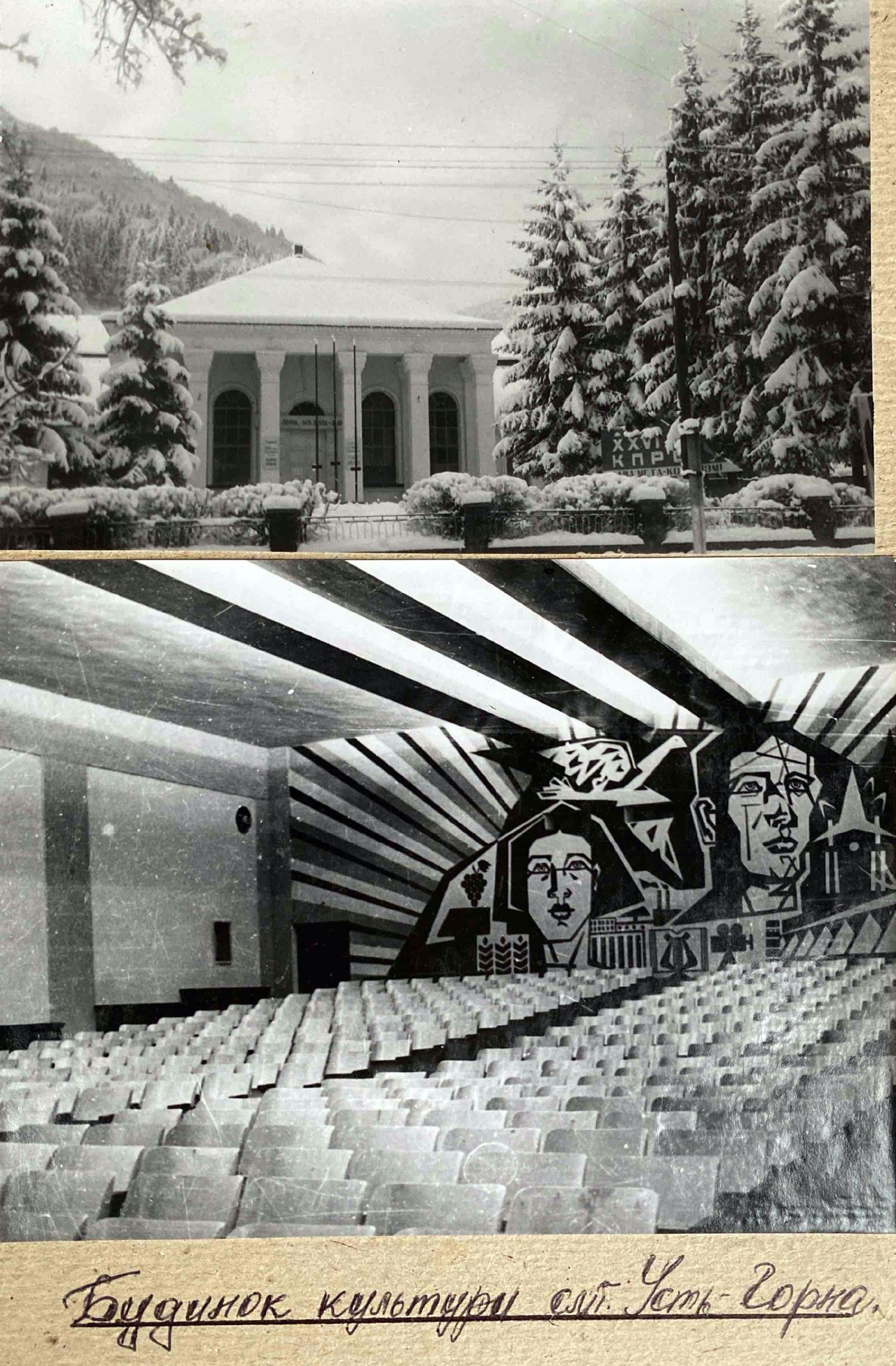

There is an unusual sign at the entrance to the village of Ust-Chorna, which is sandwiched on both sides by the wooded ranges of the Carpathians. Under the official name of the village еруку is white wooden letters which reads: Königsfeld Herzlich Willkommen — “Königsfeld. Welcome”.

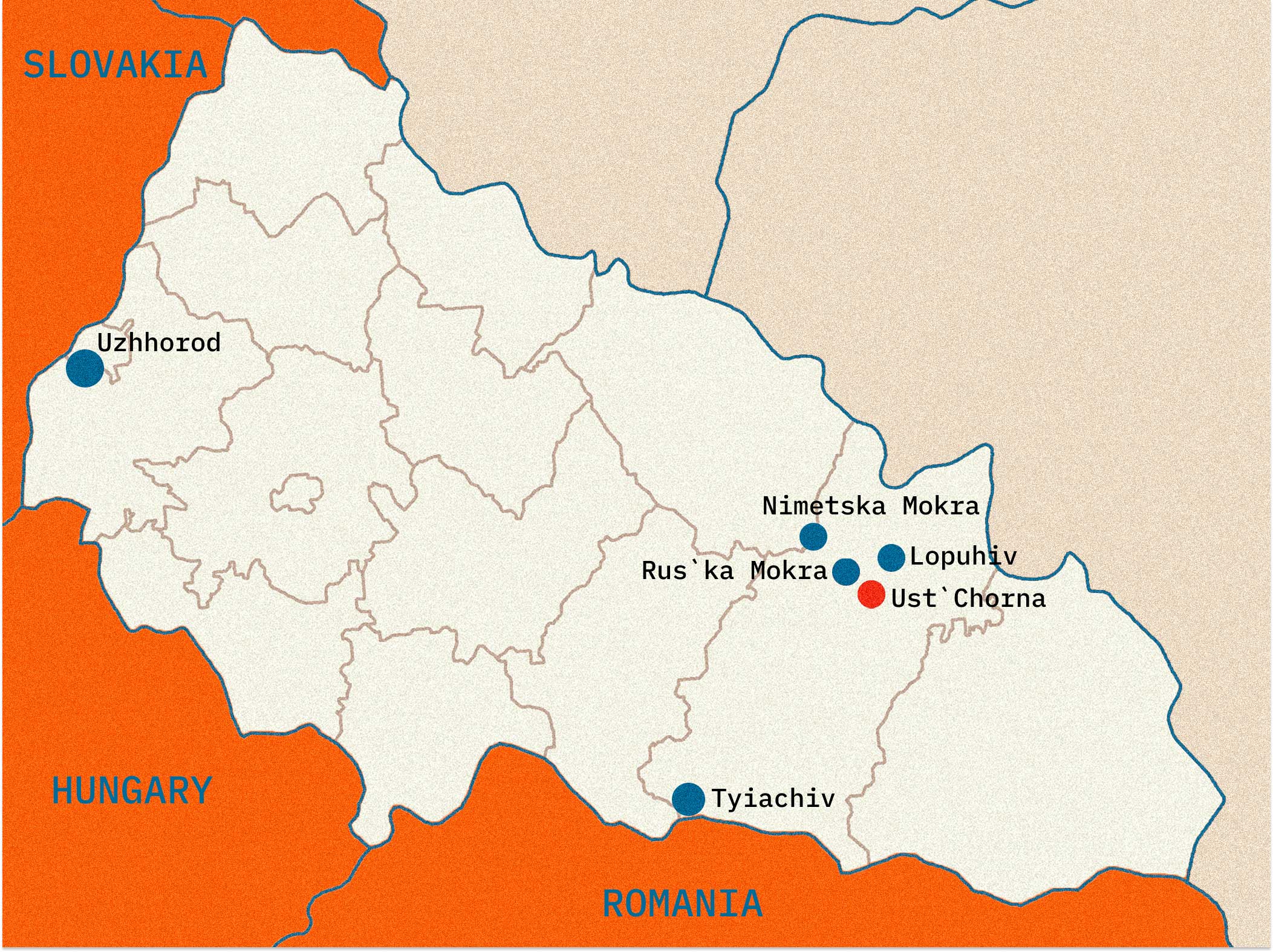

Infographic: Kateryna Kruglyk / Zaborona

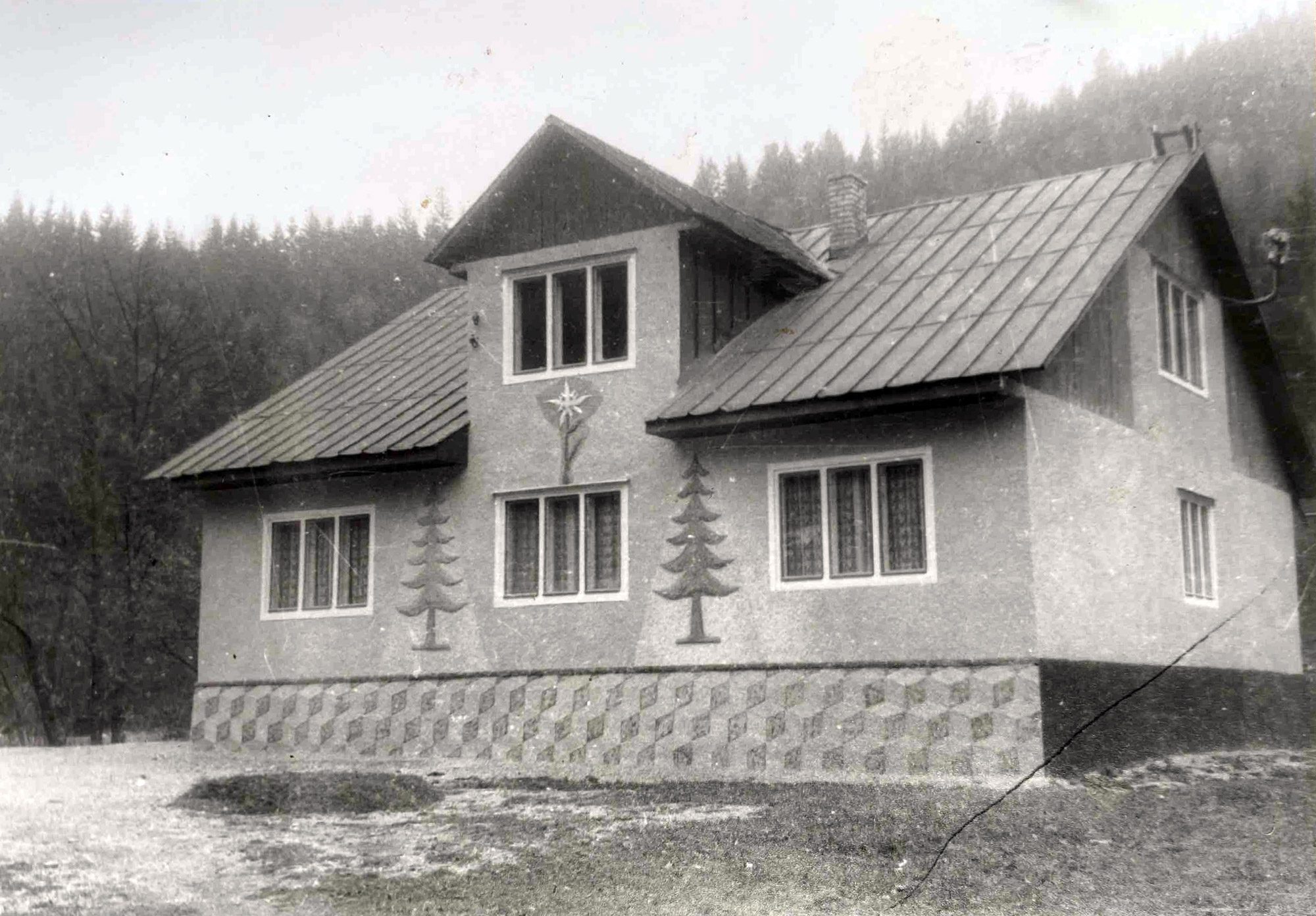

At the end of the 18th century, the Austrian empress Maria Theresa sent about 200 lumberjacks from Upper Austria here. For decades, they harvested wood for the needs of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and founded two villages here: German Morka (Deutsch Morka) and Ust-Chorna (Königsfeld).

-

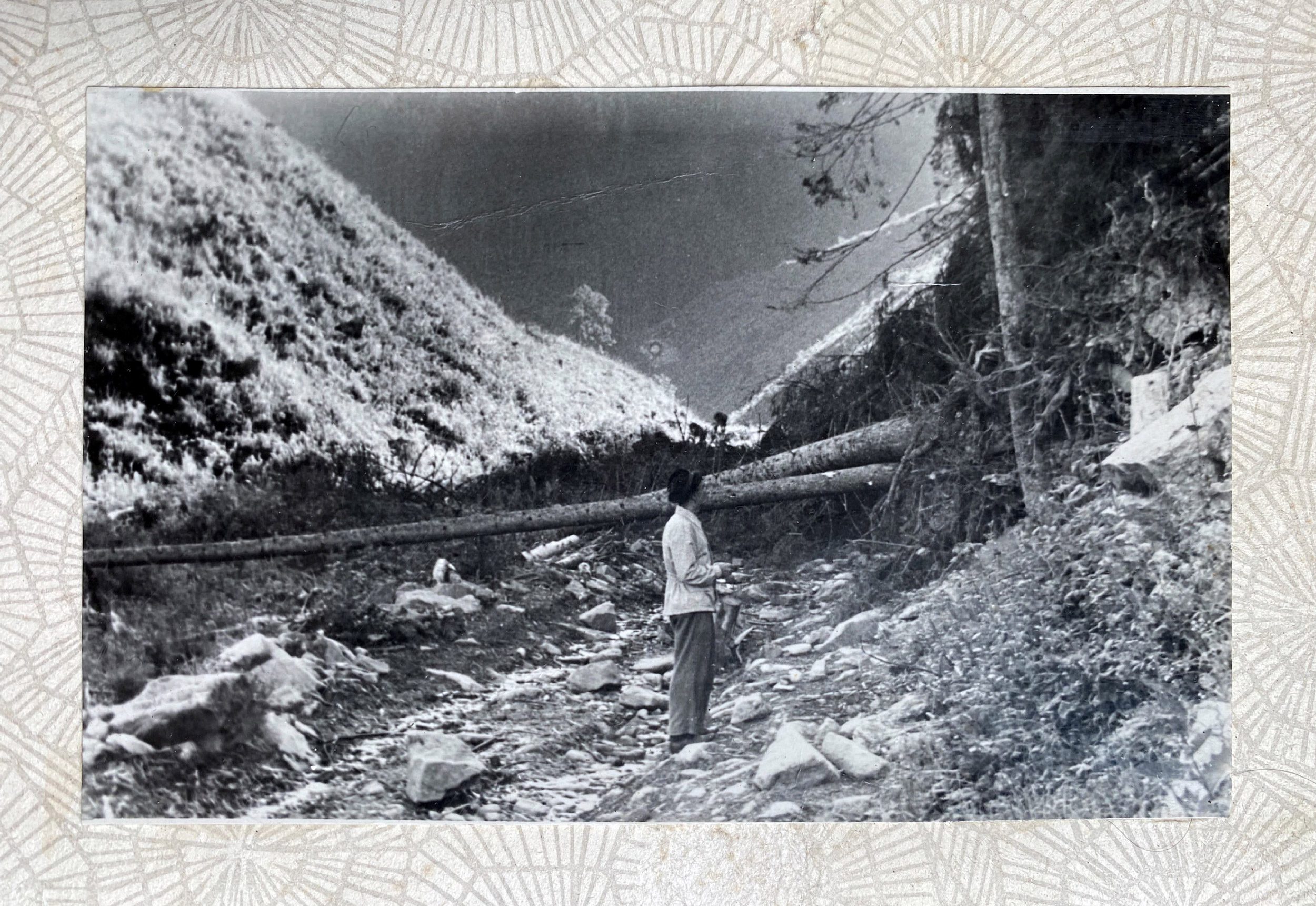

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk -

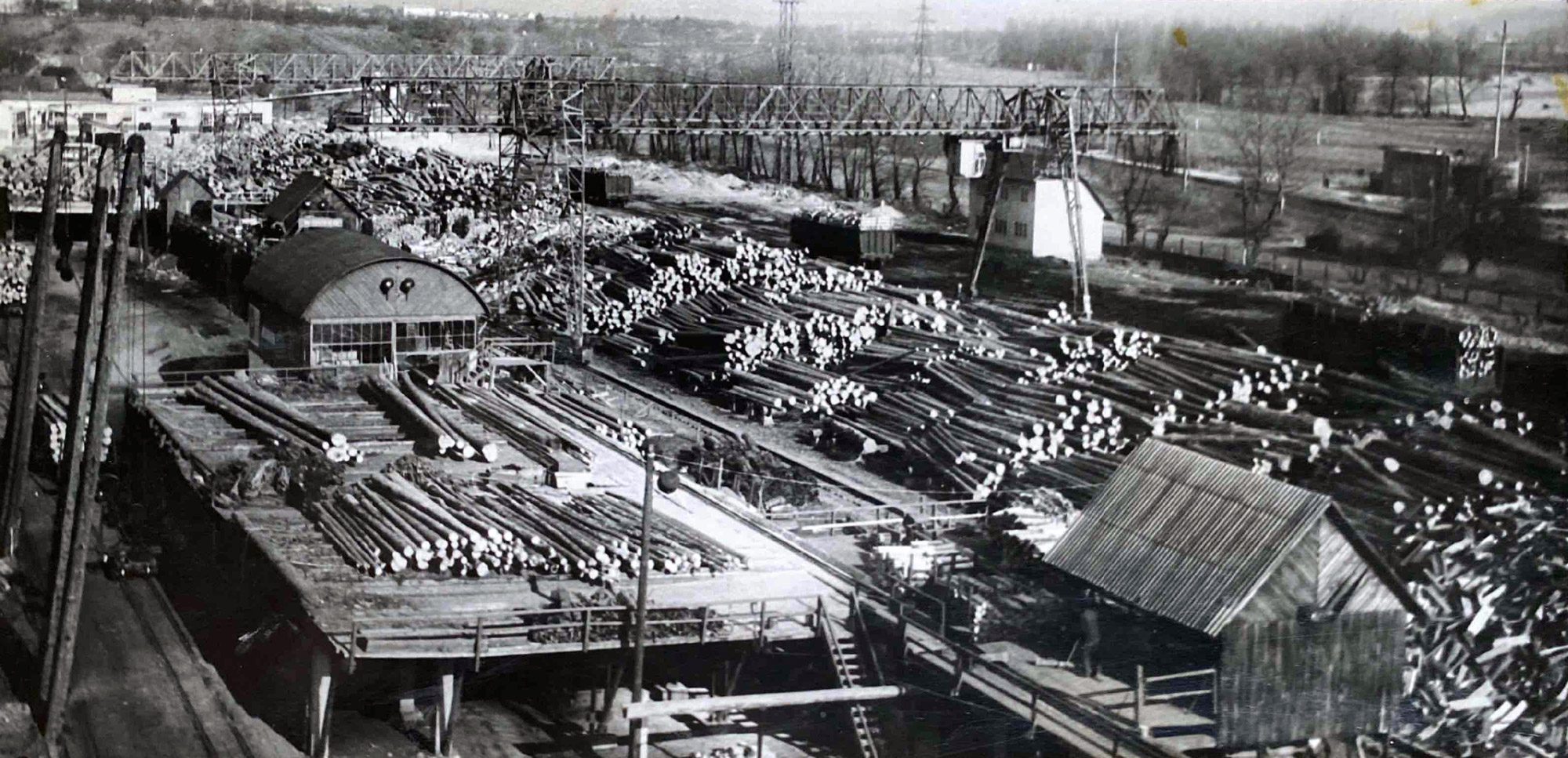

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk

In the 1920s, Czechoslovakia, which annexed the Transcarpathian lands, stretched a narrow-gauge railway along the Teresva River, which flows through Ust-Chorna. For 60 years, it transported industrial timber harvested in the upper reaches of the river, but at the end of the 20th century, the route was completely destroyed by a great flood.

After the Second World War, many German-speaking residents of these villages became victims of Stalinist repressions. The rest, who were not sent to Siberia, went to Germany and Austria after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s.

-

Composition of the forest in the village Teresva. Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk

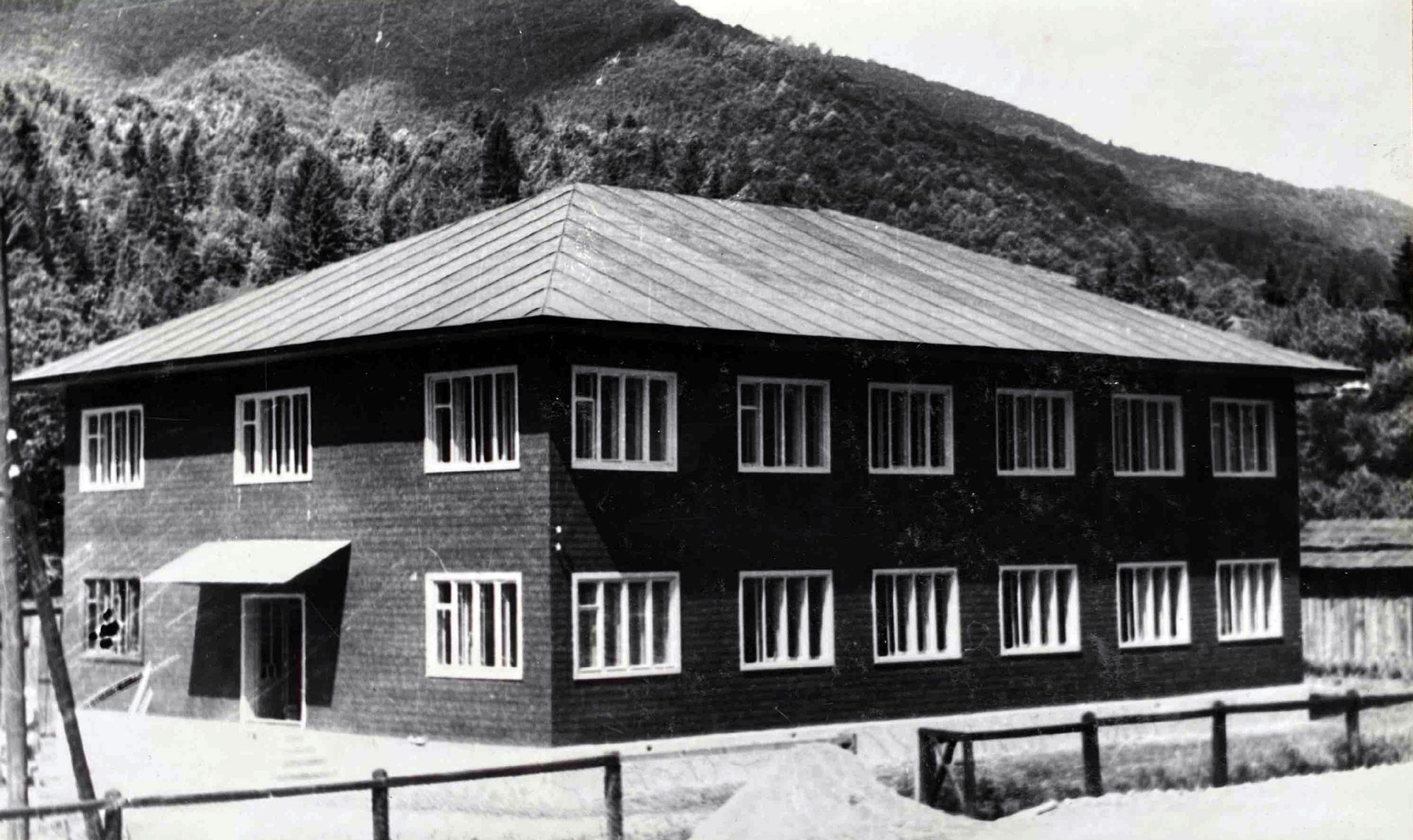

During Soviet times, one of the largest logging factory in the Union operated in Ust-Chorna. For more than 20 years, the actions of thousands of forestry workers were documented by the turner and quiet, unremarkable chronicler of Transcarpathian life Mykhailo Kosyuk.

Kosyuk was born in 1938 in the nearby village of Lopukhiv (until 1946 it was called Brustury). During the Second World War, Mykhailo and his family were forced to leave their native village due to the occupation by Hungarian troops. With the end of the war, the family settled in the village of Ust-Chorna — during the retreat, the Hungarian army burned Lopukhiv.

In a new place, Kosyuk finished 7th grade of school and got his first job — at the age of 13, his father took Mykhailo to a railway depot, where he worked as a blacksmith’s assistant, and later as a turner in a repair and technical workshop.

While working as a turner, he started taking photographs. The German Johann Plakiner lived in the village at that time. He was engaged in photography. When Plakiner’s health no longer allowed him to shoot, he began to tell Kosyuk about the craft of photography.

-

Mykhailo Kosyuk, 2018. Photo: Pavlo Bishko

Later, a souvenir shop was opened at the plant, where about 30 carvers worked on wooden sculptures of Carpathian animals and birds, and varnishers covered them with a shiny layer of varnish. So there was a need for a large number of labels for decorative products. Kosyuk took up this business. First, the artist drew a new label, after which it was necessary to make a photo. This is what Mykhailo did, shooting and printing thousands of labels on photographic paper.

-

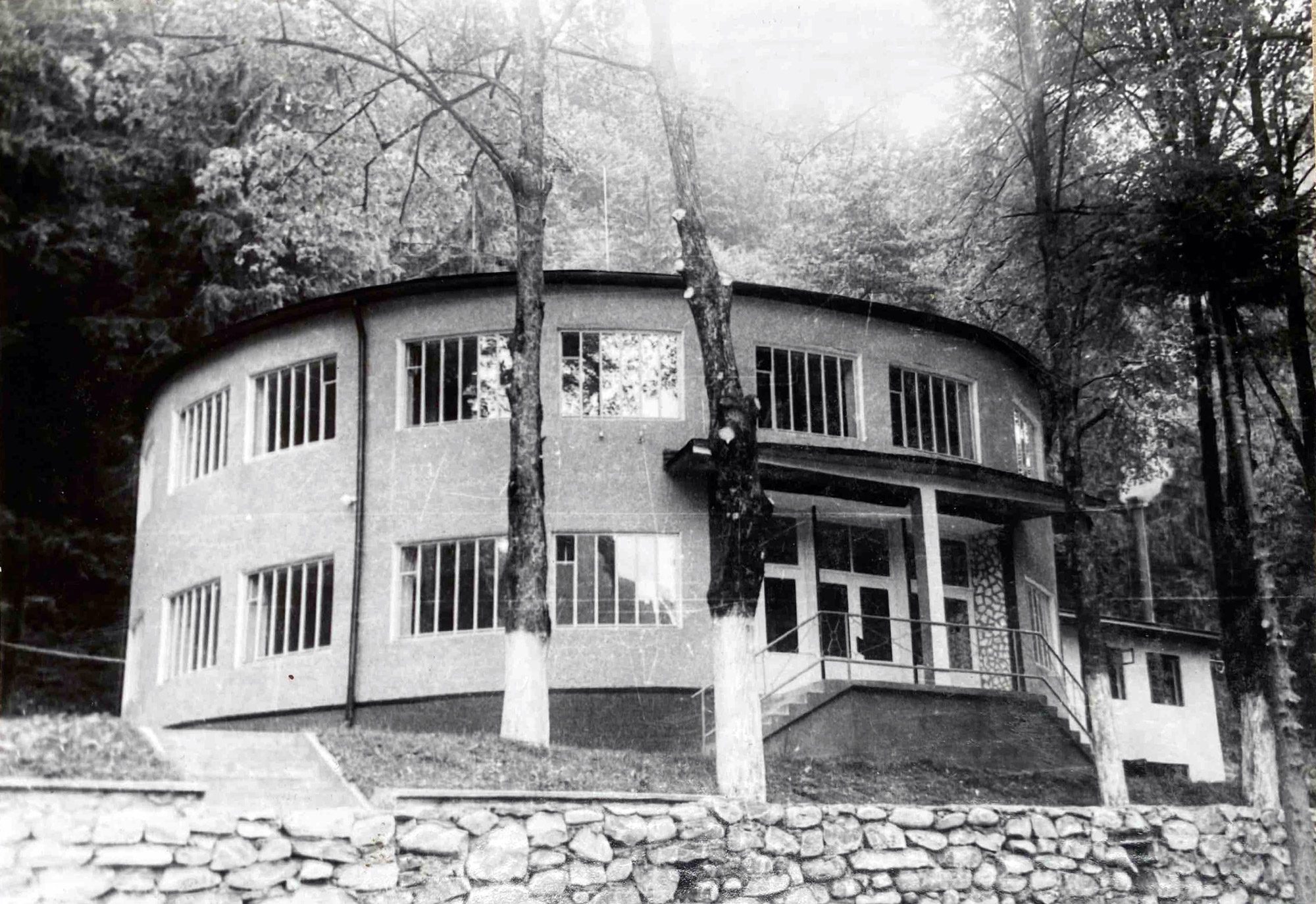

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk -

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk

However, Kosyuk primarily documented traffic accidents at the enterprise, bridges, and tracks damaged by floods, snow avalanches, and mudflows blocking forest roads. Mykhailo became a real chronicler of the catastrophes of a small, invisible world.

There were other pictures. If someone needed to take a photo for a passport or a Komsomol ticket [a document needed in the Soviet Union to get a job], Kosyuk took care of it. Once, during the change of union tickets at the company, the loggers needed new photos. But not all of them could come to Mykhailo’s studio: some worked for weeks in remote forests. Then the photographer came to the forest and took portraits there. In order for the logger to look neat in the photo, Kosyuk took a razor and a clean shirt with him. In his free time, in his home photo studio, Mykhailo Kosyuk made farewell portraits of Germans who were leaving the village forever.

-

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk

In 1964, the Roman Catholic priest Yan Maciejko arrived in Ust-Chorna from Slovakia. He became friends with Mykhailo, together with him he went to shoot landscapes in the mountains. Every year at Christmas or Easter, Maciejko invited Kosyuk to the church to film the service. The service was mostly attended by older people. Going to church, they were worried about Soviet atheism. But Maciejko trusted Mykhailo. The priest knew that the photographer would show the photos from the holiday service only to him. Later, Maciejko distributed the photos to all the parishioners present.

-

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk -

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk

-

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk

“I have a job”

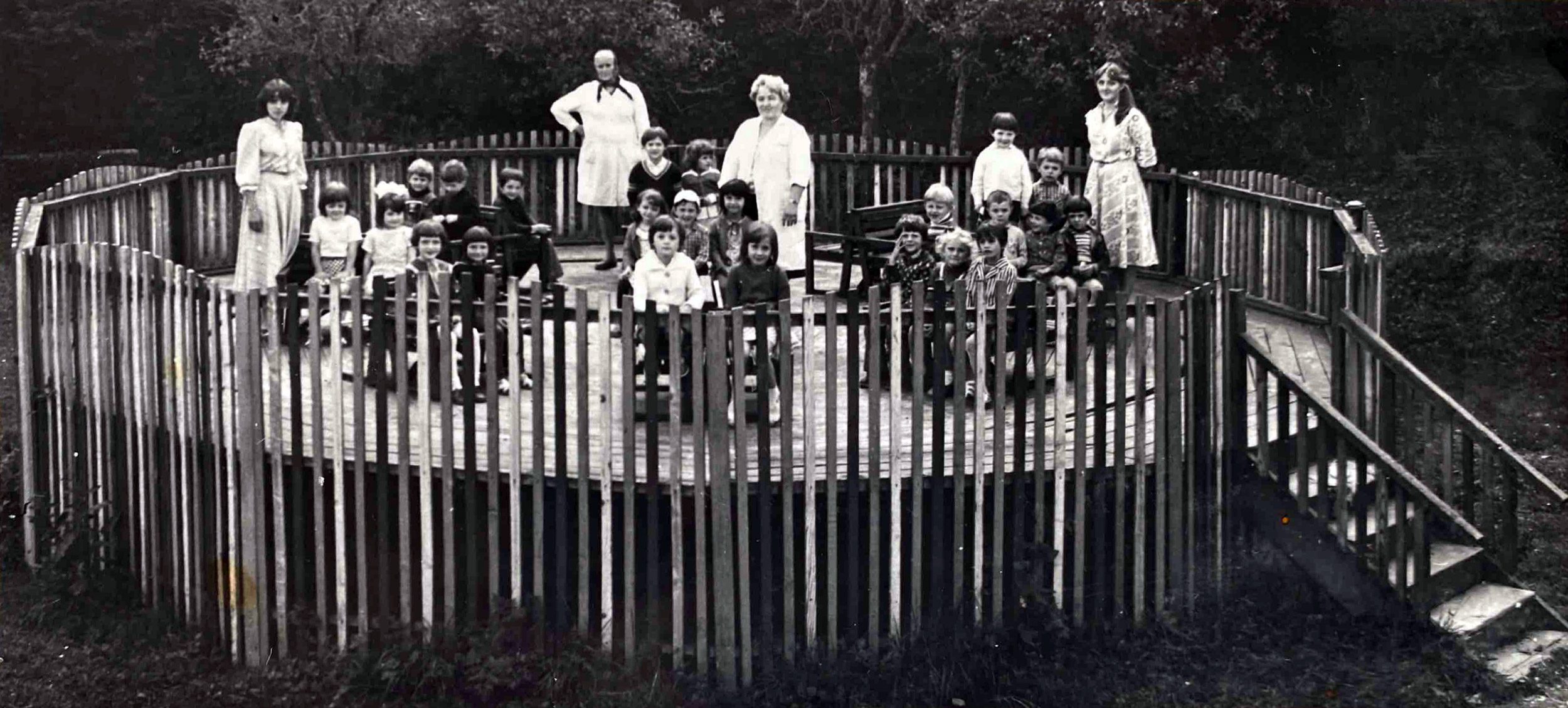

Mykhailo’s wife, an accountant in a kindergarten, always invited him on vacation to the Baltic countries or Leningrad.

“I can’t. I have a job,” answered the man. Mykhailo could not leave the village — at any moment he could be asked to photograph a wedding or a funeral.

-

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk -

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk -

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk

-

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk

One winter, due to heavy snowfall, Kosyuk could not get to the wedding by motorcycle, so he walked several kilometers. And when he was shooting three weddings in one day, he was very worried about being on time and not letting anyone down. It happened that he came to shoot a wedding, and the bride was still not ready. Then he was persuaded not to go to the next wedding, which was unacceptable for him as a photographer.

-

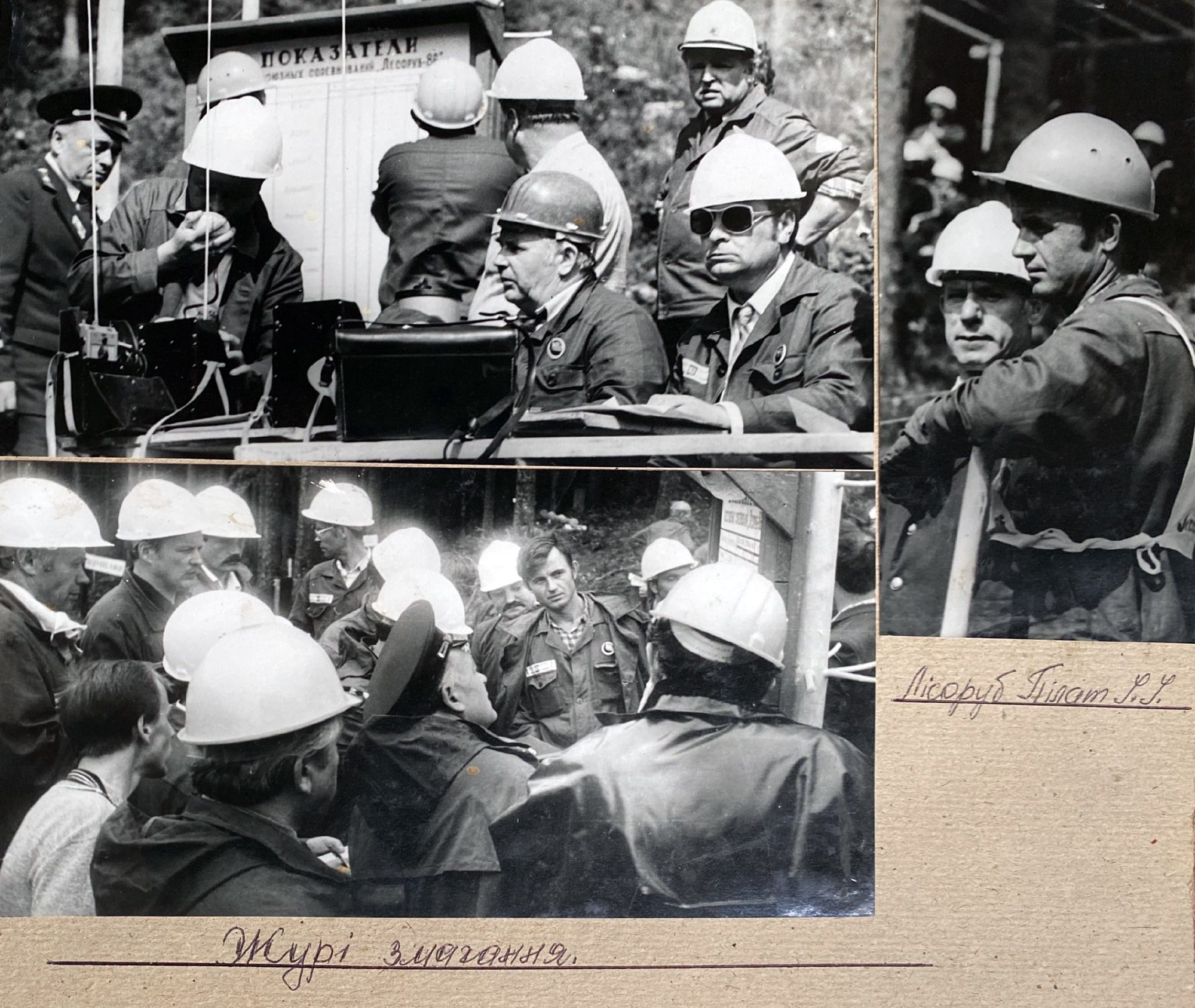

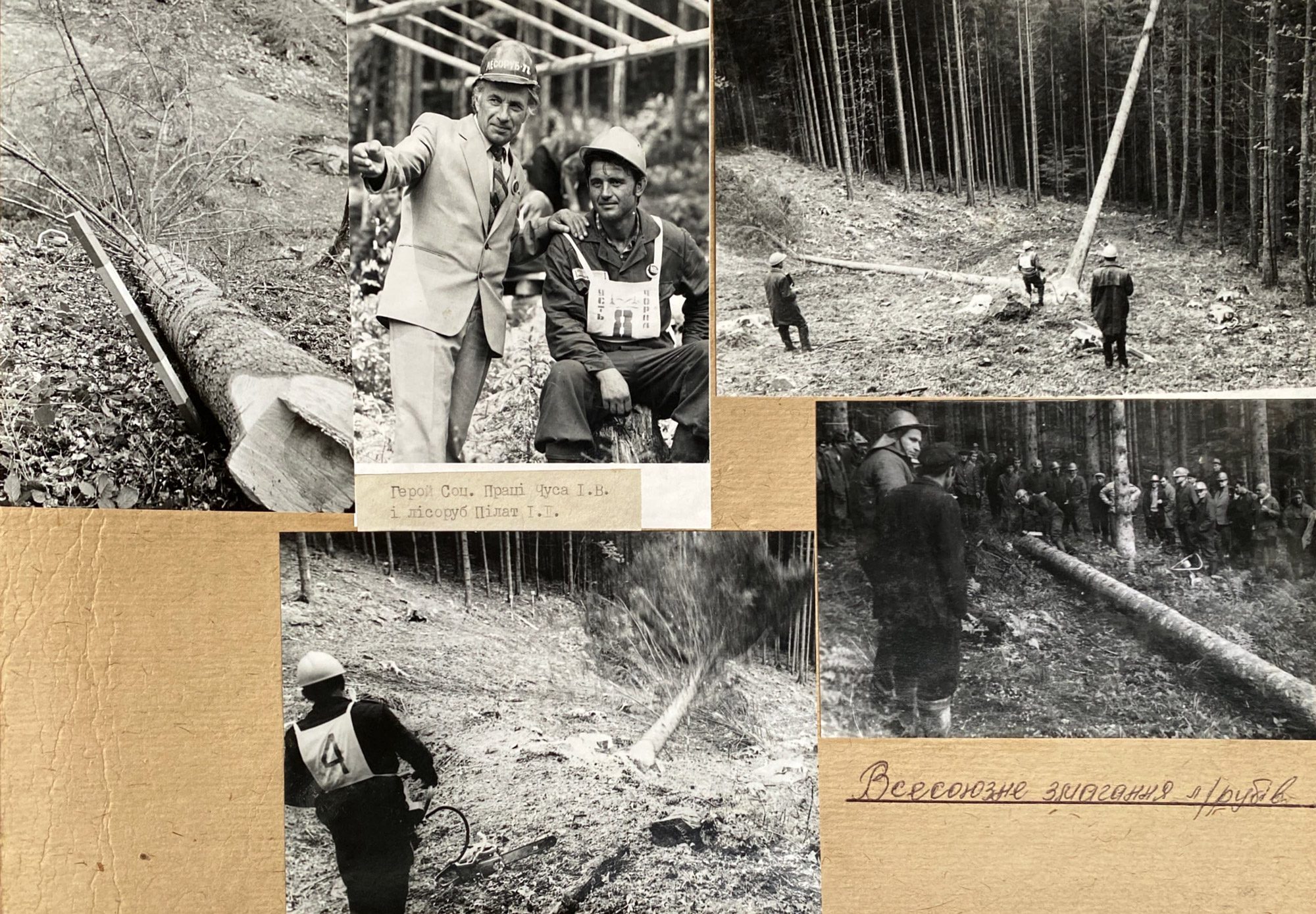

All-Union competition of loggers. Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk -

All-Union competition of loggers. Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk -

All-Union competition of loggers. Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk -

All-Union competition of loggers. Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk

Students from Uzhhorod came on an expedition to Ust-Chorna to collect snakes for embalming. The teacher did not dare to do it himself, so Mykhailo led an expedition into the mountains and caught Carpathian snakes with his own hands. Fascinated by Kosyuk’s work, the teacher suggested that he should apply for a place in the institute.

“I can’t. I have a job,” answered Mykhailo.

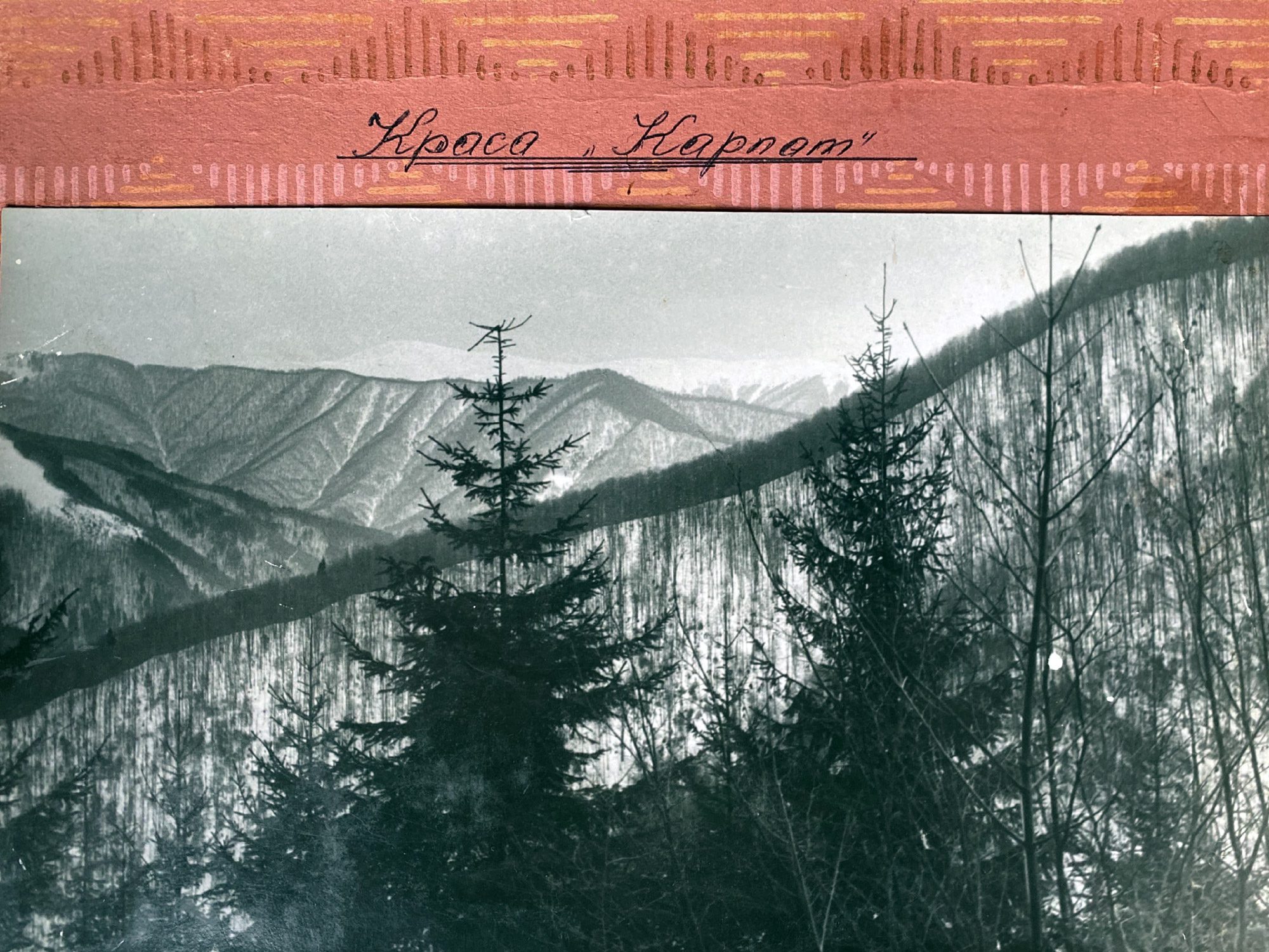

His rest was, again, work. But already in the landscapes. At first, he made photos of landscapes only for himself. But when the local Germans left Ust-Chorna, they turned to Mykhailo for the photos of their native village as a souvenir.

The last reportage

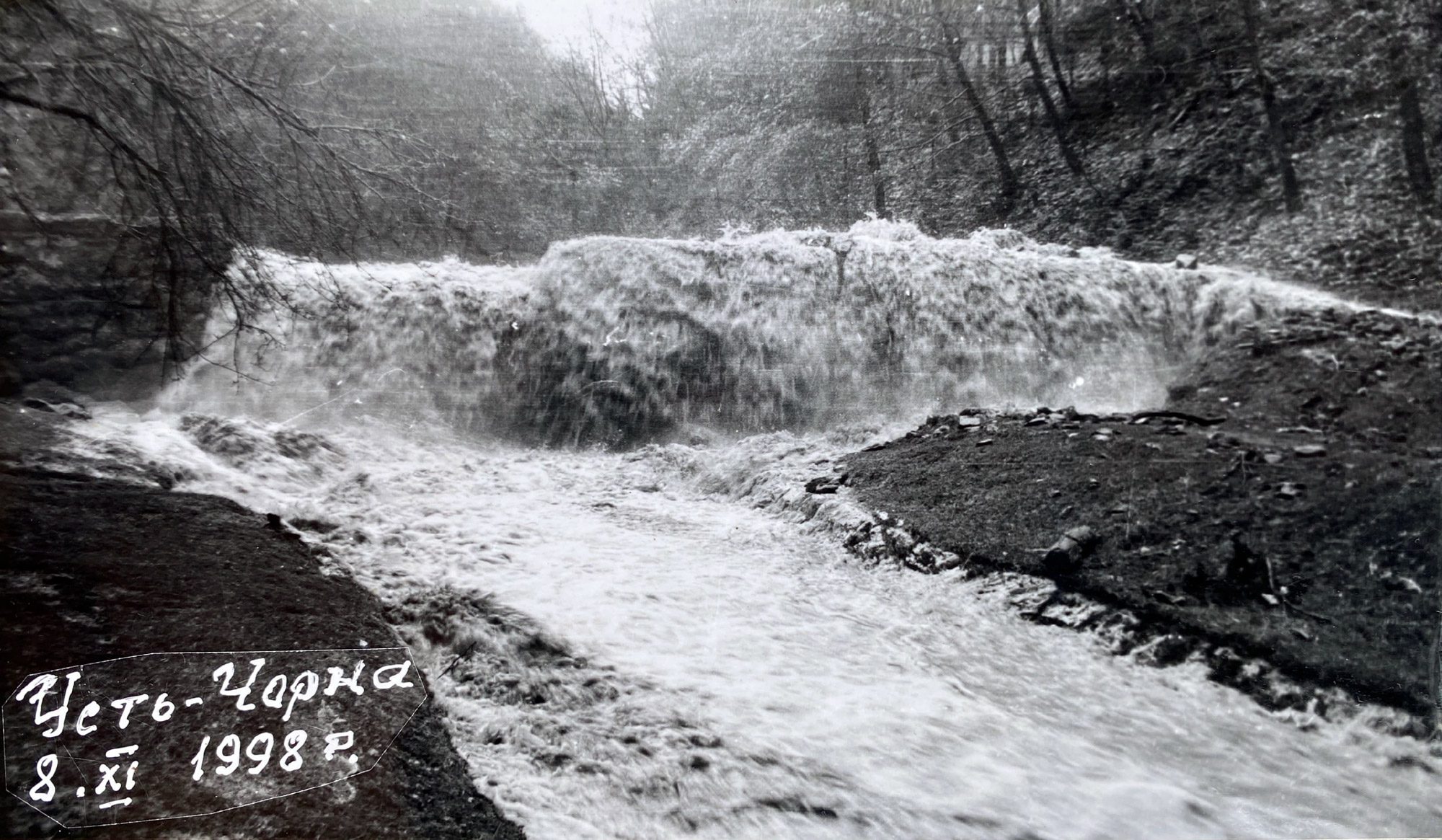

In 1998, none of the residents of Ust-Chorna thought that the Teresva River, which in summer could be crossed with only wet feet, would flood houses thigh-high in the fall.

Kosyuk documented the damage that the flood brought to his village. The flow of water was so strong that the current not only damaged bridges and railway tracks but also took whole houses with it. Mykhailo’s photo laboratory also suffered from this.

He had imagined a retirement in which he would shoot mountain landscapes. But the flood changed those plans, and filming the flood became his last reportage. After retirement, Mykhailo left two cameras for himself, which are still hanging on the wall of his room. He sold numerous lenses and cameras.

Loss of the archive and illness

Among the motorcycle, bicycle, and tools in the shed, Kosyuk kept a photo archive: ten rolls of negatives and two suitcases of printed photos. Two years ago, due to a fire, this archive was lost. Only two albums with photos, which were kept in the house, survived.

After a stroke, the photographer remained bedridden.

While still working as a turner, Kosyuk helped colleagues from the workshop to treat their eyes. He learned to remove tiny fragments that got into the eyes of the workers during careless work with metal. Last month, an older man came to Mykhailo with an injured eye. But this time Kosyuk could not help.

“And that’s how his whole life passed,” says Mykhailo’s wife. “With photography and with eyes.”

-

Photo: Mykhailo Kosyuk