“We Were Beaten and Tortured, and after Returning Either We Go to the Front Line as Meat or Back to Prison”: How Ukraine (Does Not) Return The Prisoners Abducted to Russia

Russia, along with the territories, has taken tens of thousands of Ukrainians hostage and including those serving their sentences in prisons. Prisoners in the war zone or under occupation are one of the most vulnerable categories of the population, and they are often forgotten about. The Russians take them to their territory, keep them as slaves, abuse and torture them no less than others.

The state does not fight for their liberation and does not care much about those who returned thanks to volunteers. Hanna Skrypka, a human rights activist from the NGO “Protection of Prisoners of Ukraine” told Zaborona’s editor Svitlana Hudkova more about the fate of the abducted Ukrainian prisoners.

Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, more than 3,000 Ukrainian prisoners have been held hostage in Russia. Moreover, when the Russian army fled from the right-bank Kherson region and part of the Mykolaiv region, the occupiers took prisoners to Russia. Why did they need them? To drive them to fight against their own, the Ukrainian army?

— No, they are not soldiers. Even when Russian prisoners were being recruited for the Wagner Private Military Campaign, no one tried to recruit them.

For them [the occupiers], these people are slaves. Prisoners are involved in various hard labor: they dig trenches, build defenses or serve local collaborators. And that’s if we talk about the occupied territories.

Human rights activist from the NGO “Protection of Prisoners of Ukraine” Hanna Skrypka. Photo: Hanna Skrypka\Instagram

Those deported to Russia become an element of pressure on the Ukrainian authorities. The more of them are taken, the better for the enemy. Why? We are not talking about this yet, but in the future our prisoners may become an exchange fund. They also conduct voluntary and forced passportization among them in order to wave statistics, saying that so many Ukrainian citizens have taken Russian passports.

Ukraine wants to return all its citizens from Russia. However, we hear a lot about the liberation of children and prisoners of war, but not about the exchanges or negotiations on the return of our prisoners. The government is working in this direction, but is there communication with the other side?

— No. At least not anymore. In 2022, negotiations between our Ombudsman’s Office and the Russian Ombudsman Tatiana Moskalkova continued. At that time, we were talking about exchanging or finding other ways to get them back. In 2014, we already managed to take prisoners from the so-called “DNR,” but this time the conversations ended in nothing, so communication stopped. And no one wants to talk about our prisoners anymore. But I think it should have been done systematically, not just with one or two appeals.

View of a wall damaged by a shell in the jail of Chornukhyne, east of Debaltseve on February 28, 2015. Only four of over 300 inmates are left in the jail after it was evacuated to another jail following shelling during the battle for Debaltseve. The four remaining inmates have chosen to stay, baking bread for the local village. Photo by JOHN MACDOUGALL/AFP via Getty Images

When Ukrainian prisoners are released, do they return to Ukraine? What are the ways?

— There are several ways. The first one is through the Kolotylivka-Pokrovka checkpoint in the Sumy region. Former prisoners can turn to volunteers and human rights activists for help in organizing their travel to this checkpoint: we buy tickets online, and if possible, transfer a certain amount of money.

However, returning this way has become more difficult due to changes in the rules for crossing the border. Previously, a photocopy of your passport was enough, but now you need a document issued by the Russian authorities, which takes a month to obtain. [Since August 7, 2024, this humanitarian corridor has been closed due to the escalation in the Sumy region].

At the Ukrainian border, former prisoners need to show at least a photocopy of a document certifying their Ukrainian citizenship. Without this, they can be detained until the migration service confirms their identity, which, fortunately, happens very quickly.

The second option is through Georgia. But this route has its own peculiarities too, because it goes through the Temporary Detention Centers for Illegal Migrants (TDCs). Now, according to the new rules, prisoners without original documents can get a temporary ID card at the temporary detention center, which allows them to leave Russia. After receiving such IDs, they are deported to Georgia through the Larsi checkpoint.

How many citizens have been returned so far?

— The “Protection of Prisoners of Ukraine” managed to free more than 260 people. I know that at the beginning there was another organization in Georgia that helped Ukrainians. Thanks to them, about 50 people returned to Ukraine. But those who leave Russia through Georgia mostly stay there.

Why is that?

— There are two reasons for this. The first is mobilization. Many returnees don’t even have time to undergo a medical examination and restore their documents, as they are immediately taken to the military commissariat.

Former prisoners who were recently released from prison to join Ukrainian army exercise at the base of the first assault battalion named after “Da Vinci” on June 16, 2024 in Dnipropetrovsk region, Ukraine. Photo by Andriy Dubchak/Frontliner/Getty Images

The second reason is prison again. Prisoners deported to Russia have their sentences changed in accordance with Russian law, and some serve shorter terms. Usually, it is no more than three months. But when a person returns after serving time in a Russian colony, they are put back in a pre-trial detention center to finish their sentence.

Of course, people refuse to leave. They say: we have been tortured here, and upon our return, we will either be used as meat or sent back to prison. So they stay, try to adjust, look for work and housing. Some of them, frankly speaking, are back in Georgian prisons, some are homeless.

Are the authorities trying to solve this?

— The government does not want to solve anything. We are constantly appealing to the relevant ministries, but we get no response.

That’s why we try to highlight this problem as much as possible. Fortunately, journalists and public organizations help us. And I hope that we will somehow get this whole thing moving.

The state does not need these people after their return. Unless they serve their time or are mobilized.

First, many return without any documents, and they need to restore them. Various public organizations often help with this. The second problem is that almost 90% of the returned prisoners served their sentences at their place of residence, i.e. in the territories currently occupied by the Russian Federation. Most of them are unable to return to their homes, as it’s either too dangerous or their homes have already been destroyed. We have faced complete discrimination against returned prisoners. They are not accommodated in temporary housing or shelters, they are denied everywhere because they are former convicts. They are restricted in psychological, legal, and humanitarian assistance.

Those who have relatives who left for European countries after the outbreak of full-scale war cannot visit them. The reason is that they are included in the SIS database, which contains data on foreigners who have violated the law abroad. So they are banned from entering Europe.

Various non-governmental organizations help as much as they can: we restore documents, look for rehabilitation centers, accompany people so that they can re-socialize. But it is clear that our citizens have less and less motivation to return to Ukraine.

Are they trying to keep them in Russia?

— Yes, they offer to acquire Russian citizenship for money, give them certificates for housing.

How many agree to this?

— About a quarter of those who are released remain in Russia.

And this is after all the torture?

— What difference does it make to them when they were tortured in Ukraine in the same way? Yes, our system, unlike the Russian one, may have become a little better, but prison torture is still a reality in many cases. For example, the Northern High-Security Correctional Colony No. 90 in Kherson. People who have been in prison for many years get sent there, some of them started their prison career in Soviet prisons. They say that we may have better conditions, but they experienced torture here, just as they did in Soviet prisons. Therefore, there isn’t much difference for our convicts.

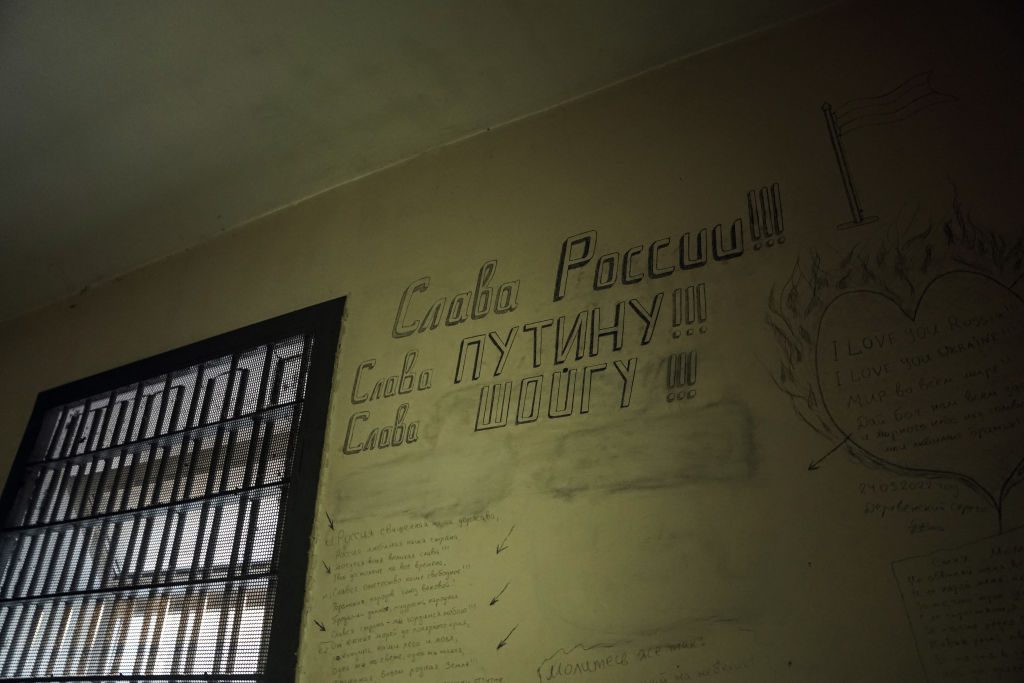

Pro-russian inscriptions are seen on the wall at a preliminary detention centre which is believed to have been used by Russian forces to jail and torture civilians on November 14, 2022 in Kherson, Ukraine. Photo by Taras Ibragimov/Suspilne Ukraine/JSC “UA:PBC”/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images

Are our prisoners treated worse in Russian prisons?

— Yes, it is worse. But this is incomparable to what is happening in the occupied territories, where our prisoners face horrific torture, although less than the civilian population. Because prisoners are not political, at least in prison it is difficult for them to express their position. So, as they said, if you sit quietly, sign everything they give you and don’t ask questions, they won’t beat you.

Do international organizations or other countries help in the return of deported Ukrainian prisoners?

— We are only looking for donors who help with money. There is no other help from other countries or our state. We are the only organization that returns our prisoners.

Do our prisoners in Russia want to return home?

— Yes, they do. All of them do. And those currently serving their sentences call us or their relatives and ask: “Take us away from here. We are ready to serve our time in Ukraine, just take us away.” Some say that they are ready to go to the military, and there are many of them.