Until 2014, journalists liked to call Luhansk the “Far East of Ukraine” Now it is the capital of the so-called “Luhansk People’s Republic”, but, despite the significant pro-Russian sentiments in the city, Ukrainian culture has been developing there. Exclusively for Zaborona, journalist Svitlana Oslavska recounts the history of the STAN youth organization and how the underground culture of the easternmost regional center developed before 2014. Today, STAN is based in Ivano-Frankivsk. It helps develop the skills of young activists, and makes educational and cultural projects with an emphasis on social diversity, human rights and civil society development.

Early 2000s — opposition and isolation

In the early 2000s a recent school graduate from Crimea came to Luhansk – after failing the entry exam in Moscow – where he began to study tailoring and sewing at a local university. The Crimean wore a long “haier” and a peace sign around his neck, wrote poetry and looked for similar-minded informal friend circles. He learned about an organization where “they tell the truth about their own and others’ texts.”

“It was the creative association called STAN. All venerable writers passed through this place. Because they read theirs text, and they were told that it was shit,” Yaroslav Minkin remembers his arrival to STAN.

In 2008, on the basis of this creative association, he co-founded the public organization STAN, together with Konstantin Skorkin and Olena Zaslavska. For now, the literary group STAN loves anarchist aesthetics, opposes officialdom, pathos and Soviet culture.

The literary life of Luhansk at that time seemed like a swamp to young people, and the official culture “barren”, recalls Skorkin. The young authors did not want to publish their works in collections of “mass graves” at the expense of the city authorities. As Olena Zaslavska explained in an interview with Ukrainian Week in 2011, the Stanovites wanted Donbass to “finally wake up from its slumber.”

This “awakening” took place against the backdrop of a group of influential politicians, including Oleksandr Yefremov, who had came to power in Luhansk. He is called the father of Luhansk separatism, and he is the “father” of the destruction of Luhansk’s industrial sector. One by one, the region’s enterprises went bankrupt, accusing the politicians in Kyiv of it, while at the same time developing the myth of the Luhansk region’s self-sufficiency. At the same time, in 2000, Vladimir Putin became president of the Russian Federation, and in the region there were societies and associations that promoted the pro-Russian system, and published large editions of newspapers under names such as “Slavic Brothers”. It turns out that the minds of many unemployed people were a good breeding ground for such ideas. Concerning the humanitarian policy of Luhansk, the tone was set by the regional foundation “Blagovist”, which had a strong Orthodox bias.

Those who represented the underground cultural movement were both in opposition to this official culture of Luhansk and in isolation from the modern culture of the rest of the country. The isolation was deepened by the fact that they wrote mostly in Russian, and therefore, unfortunately, were not always welcome guests at literary events and in literary collections. This affront to Luhansk residents concerning such a policy – or rather the lack of a policy to include Russian-speaking Ukrainian authors in the greater Ukrainian context – would be echoed in 2013-2014. Intercity trains did not yet exist, and hitchhiking was the most accessible way to get to know the country. As the poet Lyubov Yakymchuk, who joined the group in 2003, recalls, the environment of STAN was quite closed and only “opened” shortly after the Orange Revolution. After that, Luhansk residents began to travel more around Ukraine and to participate in the Ukrainian literary sphere.

2004 — an important milestone

The point is not that the Orange Revolution radically changed anything for people in Luhansk, but that they and the residents of other cities in the region mention 2004 as an important personal milestone.

For the first time, protests in Kyiv forced someone to publicly justify their position: pro-Ukrainian, pro-European or pro-Russian. Some people first felt the divisions in society – conflicting views and the influence of propaganda. At the same time, the country was distributing materials about “three varieties of Ukrainians” directed against Yushchenko: the East was designated as the third aforementioned variety. At the same time, in 2004, in the Luhansk region, in the city of Severodonetsk, an alternative to the protests in Kyiv, was held by a separatist congress with the participation of Moscow mayor Yuri Luzhkov, where the events on the Maidan were called the “orange sabbath”. The organizers of that congress, in particular the above-mentioned Yefremov, were never punished, and this is often mentioned by the locals when you ask them about the reasons for the events of 2014.

Konstantin Skorkin, one of the co-founders of STAN, calls the Orange Revolution the first school of public activism for his generation – a generation which was at the time around 25 years old – and the first experience of confrontation with the authorities. He adds that many representatives of underground culture supported it then, which was not the case with most city residents:

“Luhansk cannot be compared to other cities of Ukraine, where drastic changes have begun and continue to this day. In Luhansk, it was all weaker, but it still happened, and it should be remembered.”

The Orange Revolution would have far-reaching effects for culture in Luhansk. Perhaps one of the most notable was the visit of Yuri Pokalchuk – for the first time, a famous Ukrainian-speaking writer had come to Luhansk to present their book. Pokalchuk then said that Luhansk was an island with a unique culture. The writer died in 2008, and the people of Stanivtsi organized a rally in his memory, where they warmly remembered Pokalchuk as a man who did a lot to turn Luhansk from an island to a peninsula.

2008 and after – art provocations

During these years, members of STAN held several underground events, including the Art Terrorist Festival “Uprising”. Poems were read in the tram, musicians played, pictures hung on the handrails – it was fun and outrageous. For Luhansk in 2008, and for any Ukrainian regional center in 2008, it was cool. STAN presented it as a protest against the dismantling of tram rails in Luhansk – against the destruction of environmental and social transport.

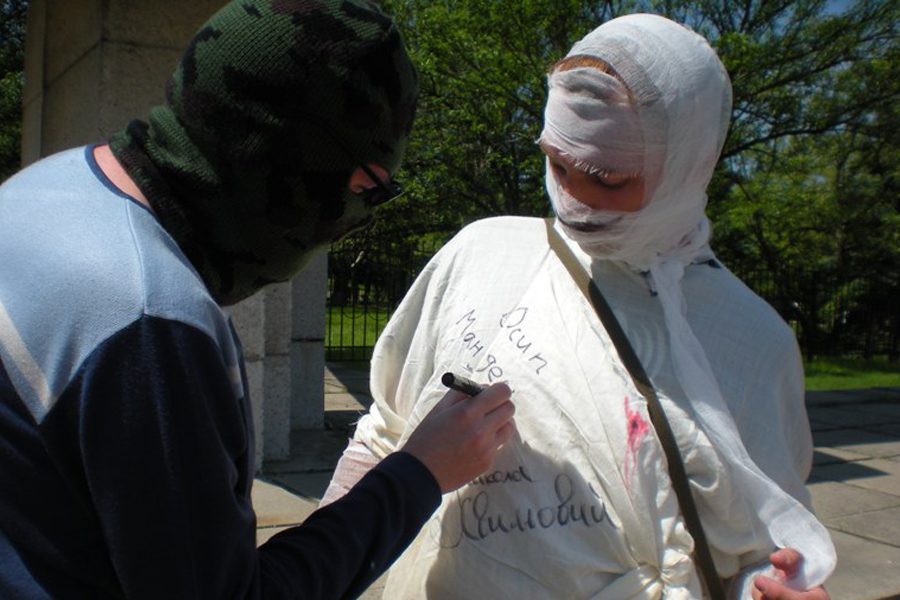

There was also the “Artistic exploration of people’s attitudes toward Stalin”. Yaroslav Minkin walked around the city, wrapped in bandages, which were painted with the names of those killed in the repression. He said he was Stalin’s mummy, and had risen because many people wanted a tyrant again.

This took place in a city where Orthodox organizations supported by the Moscow Patriarchate were active. These Orthodox organizations were against Europe, gender and homosexuality. And the city which in 2010 voted mostly for Viktor Yanukovych, who became president.

Did the people of Luhansk love their president, who was also from the region? At the least, they had voted for him. Here it is worth mentioning another of STAN’s provocative performances. Artist Vyacheslav Bondarenko, also known as Slava Bo, made an icon of Yanukovych from a box of Svitoch candies in 2011. And with it he performed “Walking in Circles”. Slava Bo recalls that one of the goals of the march with the Yanukovych icon was to learn more about people’s attitudes toward the president. They approached people and showed the icon without saying anything. And here’s what the “exit poll” showed:

“People spat, turned up their noses. Nobody was engaging”, he recalls.

2010s – from provocations to constructiveness

There were many outrageous events, but over time Stanovites grew up and came around to systematic work in the culture sphere. STAN was a partner of the Docudays Human Rights Documentary Film Festival in Luhansk, and organized its own festivals. It worked with human rights activists, and in 2013 they held a rally in support of a Nigerian student at a Luhansk university, Olaol Femi, who was illegally accused of attempted premeditated murder of four people.

According to Skorkin, the young rebels grew up, saw how cultural life was managed in other cities and states – and with this experience began to do something different in Luhansk. In 2012, STAN took part in a cultural mapping project and created the Luhansk Cultural Map, for which all city cultural organizations contributed, conducted surveys and developed recommendations. Only they would not have time to use them.

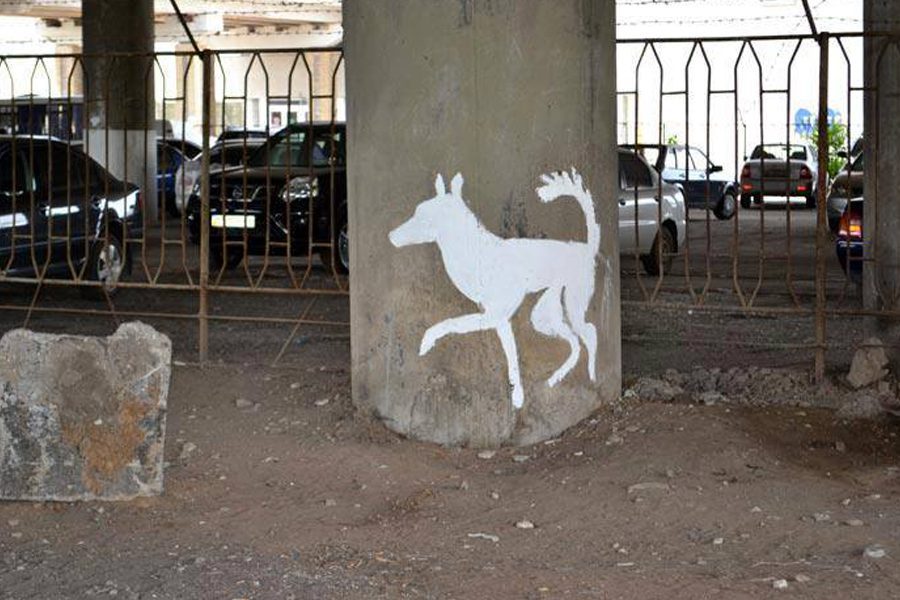

At the same time, STAN began to take part in international cultural projects and bring foreigners to Luhansk. In the spring of 2012, the Polish artist and publisher Artur Wabik arrived. Based on Serhiy Zhadan’s novel “Voroshilovgrad”, he created a comic book, and then decided to draw graffiti based on this comic in the former Voroshilovgrad itself. But when the artists began painting on the pillars of the bridge, the police appeared and a dozen of bystanders. Although Wabik wrote in his memoirs that he did not understand the discussion, he nevertheless grasped its essence, not only about this specific mural, but about the conflict of values in Luhansk society in general:

“The discussion was not so much about a formal resolution to the issue as about answering the fundamental question, ‘Why and who needs it?’ Young people argued that it was necessary, and older people said that it was unnecessary, even harmful. I got the impression that the discussion between Ukrainians was not so much about us as about certain general principles. Tradition and modernity fought in front of my eyes. The Soviet world defended itself from the onslaught of the Western world.”

While STAN focused more on institutional work, the “Russian world” organizations in Luhansk also became more professional. Round tables on the Eurasian Union were held in posh restaurants, where organizers quoted Putin, and guests from Russia uttered maxims about the moral crisis in Europe.

Yaroslav Minkin mentions one of the following events, to which STAN was invited:

“They said that America wanted to capture us. Spirituality, morality, Slavic values, space, aura – it was a radical far-right discourse on the ‘Russian world’. And most cynically – they gathered under the roof of the Gorky library, which was partly funded by the United States.”

Such were the differences of public life in Luhansk until 2013, when all the hidden confrontations came to light.

2013 – disintegration

In 2013, the culture of Luhansk underwent changes similar to those in the rest of Ukraine. The above mentioned professionalization had resulted in new initiatives. For example, artists and activists undertook to revitalize the post-industrial space of the “10th factory”, which was launched in January 2014.

In 2013, as in 2004, informal culture was largely in favor of the Maidan Revolution. Of course, not everyone supported the protests in Kyiv, and there was a split among STAN: one of the key figures in the union, Olena Zaslavska, did not accept Euromaidan and broke with the organization. She later supported the so-called “Luhansk People’s Republic” and became one of the main pro-Russian and separatist poets of occupied Luhansk.

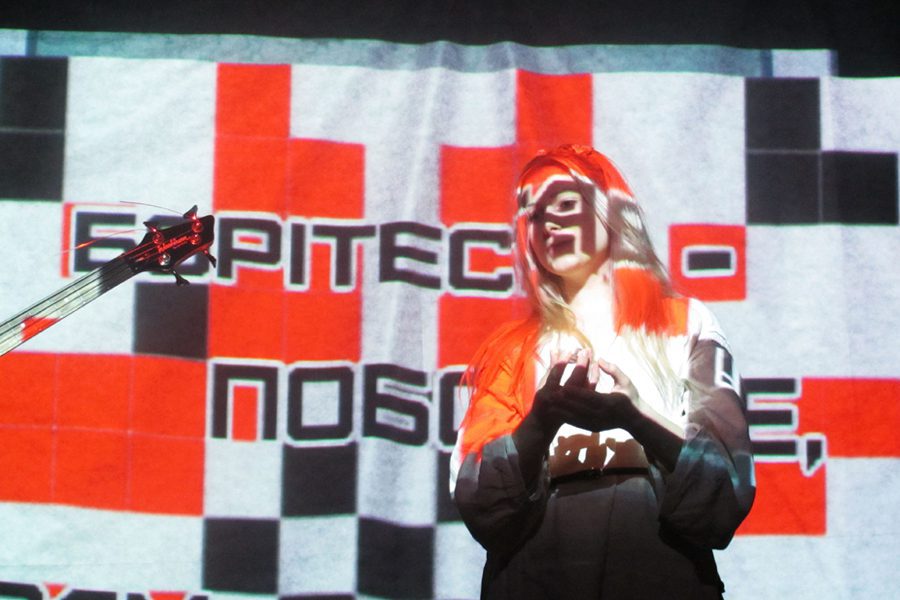

The first rallies of Luhansk Euromaidan took place in late November 2013. On March 9, 2014, separatists seized the Luhansk office of the Security Service of Ukraine. On the same day, the Shevchenko Fest took place in the “Chillout Donbass” art cafe. There were musicians, poets, an exhibition of posters based on Taras Shevchenko’s aphorisms, and a book fair. As the co-organizer of the event Anastasia Medyanyk recalls, the owner of the cafe said: “We will close the doors – and everything will be fine.” And so it happened – when the audience gathered, the doors were closed and the festival was held.

At first, activists laughed at anti-Maidan demonstrations, where participants held placards calling for members of STAN, but did not even know what these people looked like. And then, Minkin recalls, lists of “fascists and their henchmen” with telephone numbers and addresses began to be spread on social networks.

Some left the city earlier, some later. Some were held in captivity, like the author of the Yanukovych “icon” Slava Bo. Some stayed. Olena Zaslavska, one of the former leaders of STAN, became an active member of the “republic”, performed with the agitation brigade in the frontline cities and joined the “Union of Writers of the People’s Republic of China”. Konstantin Skorkin will not support the separatists and left Luhansk. Today he lives in Moscow and writes for the Carnegie Moscow Center.

Yaroslav Minkin moved to Ivano-Frankivsk, where he would continue STAN in a somewhat new way. Now this youth NGO works with youth education, human rights, social diversity and democracy. The experience of street actions is sometimes mentioned. In 2016, during the UkraineLab forum in Berlin, Minkin initiated an action of cultural diplomacy. Its participants stood on the street with various signs that were supposed to involve passers-by in the conversation, for example, “I’m a Ukrainian mother to be, ask me.” Minkin stood with a sign “I am from Luhansk.”

After 2014 – is Luhansk still there?

“I see that many people still don’t believe me when I say that Luhansk doesn’t exist,” wrote artist Andriy Dostlev in 2011. In this text, popular at the time and published on Livejournal, he argued that Luhansk was a myth invented under Stalin, and in fact there was no such city. Not all readers understood the irony.

Artist Artur Wabik:

“I often ask myself: where are all the people I met in Luhansk today? Where are the policemen from the station, the students from the Church of St. Tatiana, the rune-covered musicians, the black dancers near the monument to Lenin? Where now are Start, Nastya, Oleksiy, Anna, Yevhen, Yulia and Zhenya, who disappeared from Facebook? I don’t read Cyrillic well, but it seems to me that none of them stayed in Luhansk. Is Luhansk still there at all?”

Luhansk is still there. But what seemed like a “peninsula” ten years ago is now an increasingly distant island seen from the shore.

Interviews with Vyacheslav Bondarenko, Konstantin Skorkin, Lyubov Yakymchuk took place in 2016 as part of the project “Luhansk’s Art & Facts – Preservation of Donbass Cultural Heritage”. As part of the same project, Artur Vabik shared his memories.

Photos provided by the leaders and authors for the project “Luhansk’s Art & Facts – Preservation of the cultural heritage of Donbass”, as well as from open sources.

Translated by Kate Garcia