From 29-30 September 1941, around 34,000 people were shot in Kyiv’s Babyn Yar. According to various estimates, up to 150,000 in total were killed there during the war. And although many people speak of the Holocaust, some still disbelieve it and anti-Semitism continues to flourish. Journalist Alyona Savchuk explains the essentials about the Holocaust in Europe and Ukraine.

Why should one even know about the Holocaust?

The Holocaust – like the Holodomor, extermination of Armenians in Turkey, Tutsis in Rwanda, Bosniaks in Srebrenica, and any other genocide – deserves to be known and remembered in order to keep people mindful about what we are capable of. History is a warning. Understanding the causes, goals, and pretexts for the Holocaust will enable recognition of them again (when or if the same reappear), improve analysis of socio-political processes, and prevent similar techniques from being used by more clever and skilled hands.

Anti-Semitism, racism, xenophobia, chauvinism, and homophobia are phenomena of the same kind – with the same manifestations and forms. No one yet knows who tomorrow’s “enemies of the people” might be in a similarly intolerant society.

Where did the name “Holocaust” come from?

“Holocaust” comes from the ancient Greek for “burnt offering.” It referred to the 1915 Ottoman Empire Armenian genocide. However, the Jewish writer Elie Wiesel began to use it in the 1940s to describe German Nazi actions during World War II. With the light hand of Wiesel, the word “Holocaust” came to mean throughout the world this one specific crime against the Jews – who themselves call Nazi policy to systematically destroy their people the “Shoah,” from the Hebrew word for “catastrophe.”

The word “Holocaust” in the World War II context has two meanings. In a narrow sense, it is the 1933-45 persecution and mass murder of Jews by the Nazis and their European collaborators. In broad terms, it is the destruction of all ethnic and social groups objectionable to the Third Reich.

Who came up with the Holocaust and why?

German nationalists tolerated anti-Semitic ideas in a milder form long before the Nazi Party, Hitler, and World War II. At the beginning of the 20th century, all Europe discussed English anthropo-sociologist Houston Stewart Chamberlain’s Foundations of the 19th Century. It depicts the Aryans as creators and engines of progress, but the Jews as a parasitic people – destroyers of civilization. Goebbels would later call Chamberlain “the father of our spirit,” and his concepts will be expanded by Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

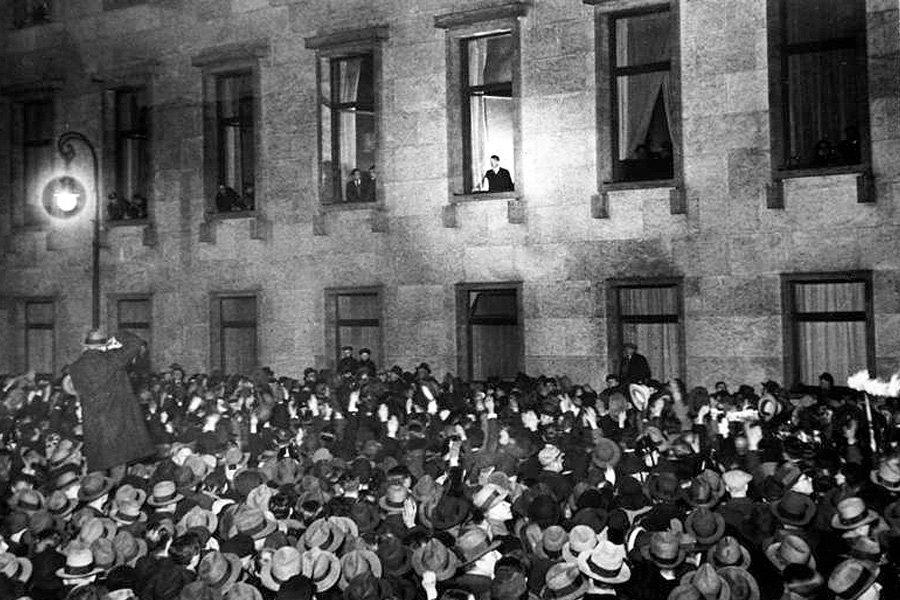

After losing World War I – amid chaos and economic recession – nationalist, militaristic, and accompanying anti-Semitic ideas intensified in Germany. Hitler’s 25-point Nazi party program openly proclaimed intolerance: “No Jew can be a citizen.” Jews were convenient scapegoats for military defeat, stagnation, unemployment, and all real or imagined German humiliations.

Having taken power, Hitler systematically made life miserable for Jews. At first, the Nazis did everything possible to make them emigrate: they were deprived of citizenship, official positions, and forbidden to have relationships with or marry Aryans. Jewish books (particularly Einstein and Freud) were burned at street actions – then Jewish houses and synagogues. Jews were not allowed to study in schools and universities, or to be treated in hospitals. Soon, the Nazis took away Jewish property and any opportunity to earn money other than by slave labor. Ghettos and concentration camps were established.

The culmination of Reich anti-Semitic policy was the “final solution to the Jewish question” – mass shootings and death camps.

How did the Nazis determine who was a Jew?

The Reich’s 1935 Nuremberg Race Laws defined who was Jewish, introducing the terms “non-Aryan” and “Mischling” (half-breed). A Jew had at least three Jewish grandparents – non-Aryan “half-breeds” had one or two Jewish grandparents. Nazis considered “half-breeds” Jews if they deliberately took a step towards Judaism – for instance, adopting the religion or marrying a Jew.

How did it all begin?

The events of November 1938 that went down in history as “Kristallnacht” – “night of broken glass” – became a harbinger of the Holocaust. This was the first large-scale Jewish pogrom led by the Third Reich in Germany. On the night of November 9-10, Nazis in many regions (mainly Hitler Youth) attacked Jews – destroying, burning, and desecrating hundreds of temples, houses, and shops.

91 Jews died that night – hundreds were wounded. And thousands were arrested and sent to the Buchenwald, Dachau, and Sachsenhausen concentration camps. Nazis burned or destroyed 267 synagogues, most of which were then subsequently razed to the ground.

This date became the symbolic beginning of the Holocaust – and November 9 is now celebrated worldwide as the International Day against Fascism and Anti-Semitism.

How many people died in the Holocaust?

Exact number of victims is unknown. The generally accepted figure is 6 million killed – reported by Adolf Eichmann and reinforced by Nuremberg Tribunal rulings. The main source of statistics is comparative data from pre- and post-war censuses and Nazi documents. About 4 million victims were identified by name.

The Reich exterminated Jewish communities at the root, so there was no one left to write down the names of the Nazis’ victims. And after the war, survivors – hoping to find their relatives alive – sometimes did not include them on the lists of those killed.

And in Ukraine?

Around 1.5-1.6 million Jews died on Ukrainian territory – about 70% of Ukraine’s total Jewish population. The country’s most researched and, therefore, most famous execution site is Babyn Yar – at that time, on the outskirts of Kyiv. Historians estimate the number killed there at 70,000 -120,000 from 1941-43. Among them – in addition to Jews – were Roma, Ukrainian nationalists, prisoners of war, partisans, underground fighters, and psychiatric patients.

The Babyn Yar tragedy climaxed on 29-30 September 1941. In just two days, Nazis shot 33,771 victims there – one of the biggest mass killings during World War II. In total, less than only 20 people were saved from Babyn Yar.

Yet there is really no master list of victims in Nazi archives?

By the end of World War II, the Nazis – realizing defeat was a matter of time – hastily covered up the traces of their crime, destroying documents and even removing the already buried human remains from mass killings. Documentation that survived the Allied offensive was immediately classified for many years – some of it still inaccessible to the general public.

For example, experts today estimate that 1.1-1.6 million victims were killed in the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp – mainly Jews. Immediately after its liberation, Soviet troops captured the death camp’s entire archive, took it back to the USSR, and classified it. So, to at least indirectly count the dead, historians study the lists of those who were deported to Auschwitz by train.

Who else suffered, other than Jews?

Nazis persecuted people because of their nationality, religious beliefs, sexual orientation, and physical or genetic characteristics. They considered some groups inferior or opposed to their regime – for instance, adherents of the Jehovah’s Witnesses religious organization were sent to concentration camps because they were politically neutral and refused to serve in the army or join other Nazi structures. Roma, gays, people with disabilities or mental disorders, the terminally ill, Soviet prisoners of war, and Nazi political opponents all suffered.

Why didn’t Jews flee Europe before the war?

Simply, Jews had nowhere to run. In 1938, Franklin Roosevelt convened the Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees, but it failed badly: Out of 32 countries, only the Dominican Republic offered assistance to Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria. Other nations were thwarted by mass immigration’s economic disadvantages and citizens’ xenophobic reactions to the concept.

With the outbreak of war and Nazi occupation of Polish lands, there were even more unwanted Jews in the Reich – and opportunities to legally emigrate were further diminished. Not even the news of mass Nazi executions of Jews caused other countries to revise their migration policies.

From the mid-1930s, neutral Switzerland allowed refugees from Germany and Austria to cross the border only for transit. It was at Swiss request that the Nazis stamped the passports of those leaving with a “J” mark for “Jew”. In 1942, Swiss leaders decided that “Persons trying to obtain refugee status solely on the basis of their race – for example, Jews – are not considered political refugees.” Hence, many German, Austrian, and French Jews were then deported to the Nazis.

So why didn’t the Jews defend themselves?

They did. At first, Reich anti-Semitic policy was unsystematic and dulled the sense of danger – people did not understand it would get worse yet. Subsequently at the end of 1938, Jews were forbidden to carry any weapons – while well-trained and well-armed Nazi troops outnumbered them many times over.

However, Jews often fought back – even when it was hopeless. Armed undergrounds arose in the ghettoes, and protest actions were carefully prepared. They didn’t want to die without a fight and desperately hoped to break through to partisans in surrounding forests, mountains, and swamps. The most famous uprising was the Warsaw Ghetto in fall 1943, when Jews fought off the Nazis for several weeks. After suppressing it, Nazis burned and razed the ghetto to the ground. In total, there were several dozen other uprisings too – among the largest: Bialystok, Czestochowa, and Krakow. Sometimes, the Nazis had to introduce tanks, artillery, and even aircraft.

Are only Nazis guilty of the Holocaust, or did Ukrainians help? Did Ukrainians help Jews?

The “final solution to the Jewish question” would have been impossible without participation of the local population – but it required little help from them. For instance, only the Nazis shot people at Babyn Yar. Yet it was Kyiv residents who told the Jews where to gather and spread rumors of their resettlement – and it was the local policemen who helped herd them into place.

The Germans recruited collaborators from occupied Ukraine into civil administration and police, who were responsible for “maintaining order” – arrests and executions. How many among them were obvious anti-Semites – as opposed to anti-Bolsheviks, or simply frightened and obedient opportunists – is not known. Joining police was also often their only alternative to forced labor.

Collaboration with Hitler’s regime isn’t limited to Ukrainian history. Everywhere in the occupied territories, Nazis found ample local accomplices to collaborate with the Reich at various levels.

Yet at the same time, more than 2,500 Ukrainians are recognized as Righteous Among the Nations. Only Poland, the Netherlands, and France can boast more of these people who saved Jews from death in Nazi-occupied Europe during World War II.

How were those guilty of the Holocaust punished?

The most famous trial of Nazi leaders was the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. Along with 10 others, Reichstag head Hermann Göring and Reich Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop were sentenced to death there; and Hitler’s Nazi party deputy leader Rudolf Hess, to life imprisonment. The court acquitted three – including Nazi propagandist and Goebbels minion Hans Fritzsche – but they were subsequently imprisoned by decisions of other courts.

Many Nazi criminals were never punished. The fate of some is still unclear: for instance, various witnesses alternately claimed Hitler’s personal secretary Bormann either died trying to break through the Soviet lines, committed suicide by swallowing cyanide, hid in an Italian monastery, or lived quietly in Argentina. Others returned to their daily lives and jobs. The search for Nazi war criminals continues to this day.

Does anyone actually believe there was no Holocaust?

Yes, these people are called Holocaust revisionists. They believe or propagate that the genocide of Jews either was not planned by the Nazi regime, or not carried out in the manner and scale confirmed by historical evidence and officially recognized worldwide: For example, imagining that Jews disappeared from densely populated areas not because of extermination, but as a result of emigration and deportation. Or that there could not be “so many” victims of gas chambers and crematoria, because such “efficiency” is technically impossible. Or that since documents haven’t been found with orders to murder Jews, it didn’t happen – and still more in that same spirit.

Revisionist views are usually anti-Semitic, neo-Nazi, and conspiratorial. They believe the Jews concocted or exaggerated the Holocaust in order to demand compensation from Germany and its allies and justify the creation of Israel – while other countries concealed “real” facts to bolster the Jewish position. Criticism of Holocaust witnesses is one of the most powerful tools in revisionist arsenals, as survivors’ accounts are indeed sometimes inaccurate, exaggerated, or contradictory.

Why is there still anti-Semitism after such a massive crime against the Jews?

And why do racism, sexism, and homophobia persist today? This is a person’s understandable fear of the other – a desire to get simple answers to complex questions and identify those who are responsible for one’s own problems.

The generation of direct Holocaust participants and victims has practically passed away – for the modern world, this is a story in books and old wives’ tales. Memory of the past is blurring, in particular (thanks to revisionists) the very word “Holocaust” is being devalued. Like “genocide,” people now use it figuratively for problems with the environment, human rights, and even tariffs.

Growing support for populists in Europe and the United States creates fertile ground for anti-Semitic sentiments as well as the spread of all forms and types of hatred in general.

Translated by Jonathan Brunson