The war in Nagorno-Karabakh continues despite an official ceasefires agreed by both sides. While most of the local population has fled, some parents stay to support their sons fighting on the frontline. They mostly stay hidden in basements because the next airstrike is never far away. In a special report for Zaborona, correspondents Emil Filtenborg and Stefan Weichert explain why people stay in basements.

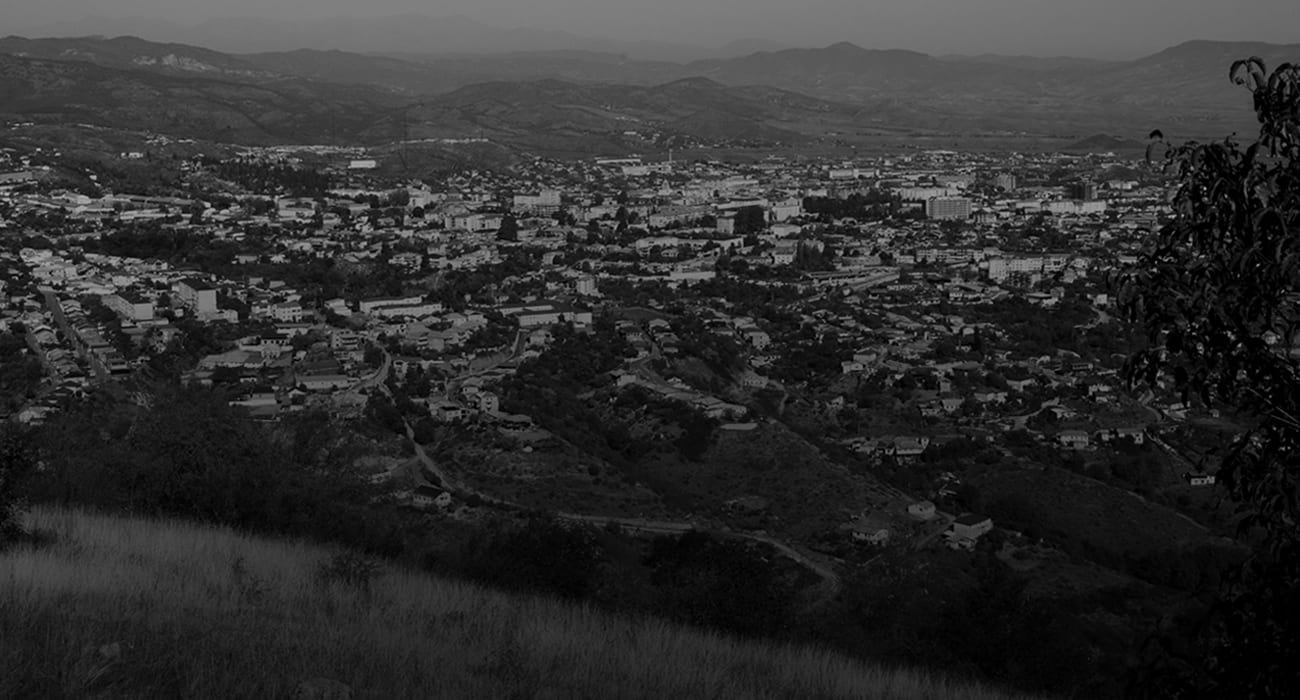

There are hardly any people left on the streets in Stepanakert besides soldiers driving to and from the frontlines. Many buildings around the capital are destroyed. Explosions have shattered some windows too. Stores are left untouched after owners fled the capital following the shelling’s that started on the 27th of September. Under a Pepsi saying, “Live for now”, moldy watermelons and red peppers are displaced, ready to be bought. But there is no seller, and they are left to rot in the sun.

Stepanakert is the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, an unrecognized republic that is completely controlled by Armenia. At the end of September 2020, a real war between Azerbaijan and Armenia began here. Both countries consider this territory their own, although legally Nagorno-Karabakh belongs to Azerbaijan.

This complex ethnic conflict has deep roots. Armenia and Azerbaijan fought for Karabakh in the early 20th century, but later, when the republics became part of the USSR, the conflict paused. The Bolsheviks decided that Nagorno-Karabakh would become an autonomous part of the Azerbaijani SSR, although it was inhabited mainly by Armenians. When the Soviet Union collapsed, Azerbaijanis hardly stayed in Karabakh at all.

At a 1991 referendum, residents declared Karabakh independent. Azerbaijan and the world have not recognized its results. The war between Azerbaijan and Karabakh’s “army”, which was actually the regular Armenian army, lasted three years. It became one of the most violent conflicts in the post-Soviet area. Now Karabakh calls itself an independent state, but in fact it is completely controlled by Armenia, which has its troops stationed and the Armenian currency circulating there. Although the conflict has been considered frozen for more than 25 years, Nagorno-Karabakh has hardly ever been peaceful.

Food is hard to find

With the recent hostilities outbreak, most people have fled Stepanakert, with only some parents of soldiers deployed to the frontline still staying. Most of them hide underground in basements, coming out for a few hours a day whenever the shelling stops. “Of course, it is dangerous, but I stay here, so my son has something to fight for,” says Sevik Ghazarian, 64, who is cooking summer beans outside a basement.

She has lived in the basement since the war broke out, and she shares it with ten others. It is cold to sleep on the floor, and some have started to become sick from living in a basement, she says. Worse, she is not sure that the basement will handle a bomb, but must be better than nothing, she reasons. Before the war, she said life was good, but it is now challenging to find food.

“This is our home. This is our land, and we will stay here,” she says, “When our sons know that we are here, they must protect us. They push us to leave and find a safe place, but we must stay here. It is our home. If we leave, they might not be able to fight,” Ghazarian says.

When asked whether there can be peace, Ghazarian says that “there will be,” but that is must come with victory. Without victory, “we will all be dead,” she says. For her, there is no middle ground. She is confident that there will be no Armenians left here if Azerbaijan wins the war. She fears a genocide like the Armenian Genocide between 1914 and 1923, committed by the Ottoman Empire. She refers to how Turkey supports Azerbaijan with drones and political support. Most of the Armenian Genocide was committed in what today is Turkey or the regions nearby. Around Stepanakert, it is not difficult to see why she is afraid of the war. Close to her basement, a bomb hit an apartment block.

Long Conflict

A bomb hit a neighboring apartment block. There are hardly any windows left. Cars have been blown to pieces, and doors are blown out, laying on the ground with intact padlocks. Сlothespins lay scattered in the rubble showing where the laundry used to hang between two buildings. We enter an apartment, where the family of five managed to leave before the explosion hit. Toys are scattered around, covered in dust. According to a family member, the mother went to the Armenian capital Yerevan with the three little children, while the father went to the frontline. Despite the devastation in the apartment, this family was lucky and left in time. In the apartment downstairs, an older woman has lost her life.

“This is a humanitarian disaster,” says Arman Tatoyan, the Human Rights Defender of Armenia, “There are targeted attacks against civilian settlements and peaceful population. They attack civilions with cluster bombs, cluster munitions, warheads and missiles. Cities and villages alike have been under heavy bombing.”

For the locals, it is hard to forgive these attacks by Azerbaijan. They accuse Azerbaijan of targeting civilians with cluster bombs, a weapon containing multiple explosive submunitions. The Azerbaijani people are accusing Artsakh and Armenia of the same crimes in Azerbaijan. An attack in the Azerbaijani city of Ganja Saturday left at least 13 civilians dead, two of them children. The Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev has promised “revenge”.

The church provides protection

55-year-old Ella, who only wants to give her first name, lives in the basement of The Surb Astvatsamor Hovanu Cathedral in Stepanakert with many others, sleeping on benches in the basement, where she has stayed since the war began. More and more has become sick in recent days, she says, because of the cold and bad ventilation.

“I have two sons in the war. Everyone here has sons in the war,” Ella says, “I do not know what is going to happen. All that I want is just my sons to come home alive and healthy.”

For now, all she can do is wait, she says, sitting with five other women, around a bench which is “a bench by day and bed by night.” They are fearful every time someone comes with news. From time to time, they make a joke and laugh, but then feel guilty for laughing and starts to think of their sons again.

“I was born here and have, been living here my whole life. I don’t want to go any other place,” says 58-year-old Irina, sitting next to Ella.

Irina calls the current war a political one. She says that it is the leadership in Turkey, supporting Azerbaijan, who is responsible. Still, she also points to Russia and other regional countries as playing a role in the current war and they need to help stop it. Irina, like the other women under the church, want everyone to do more to stop the war.

“I don’t blame the citizens of Azerbaijan. The mothers in Azerbaijan are in the same situation as us. Mothers on both sides are crying,” says Irina, “It is a political game that we don’t understand.”