After Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, the lives of those imprisoned on the peninsula changed. As the penitentiary system shifted from Ukrainian to Russian legislation, many inmates were convoyed to different regions of the Russian Federation, including the most distant. This process was worse for people with serious illnesses such as HIV. Due to the problems with medical care in prisons, the health of these people is seriously exacerbated. Some even die, since they do not receive treatment. Zaborona’s deputy head editor Yuliana Skibitskaya reports on what is happening to Ukrainian inmates in Russian prisons.

At the end of 2019, in a penal colony in the Adygea Republic, Russia, 33 year-old Crimean Andrey Titkov died. Two years earlier he had been sentenced by Dzhankoyskiy court for the theft and unlawful possession of arms. From Crimea, Titkov was transferred to a Russian penal colony. According to those who spent their sentence with him, “he burnt out in just two months”

Titkov was HIV-positive, and complained to his lawyer that in the penal colony he was not receiving antiretroviral therapy. “The colony’s administration deliberately wasted time, and didn’t give lawyers access to his medical card” claims lawyer Rustam Matsev of “Legal Initiative”. This organisation helped HIV-positive inmates in Adygea. Matsev continues: “He [the lawyer] puts a question forward and is rejected. He makes an appeal, but this takes even more time. As this drudgery wore on and on, our client simply died.”

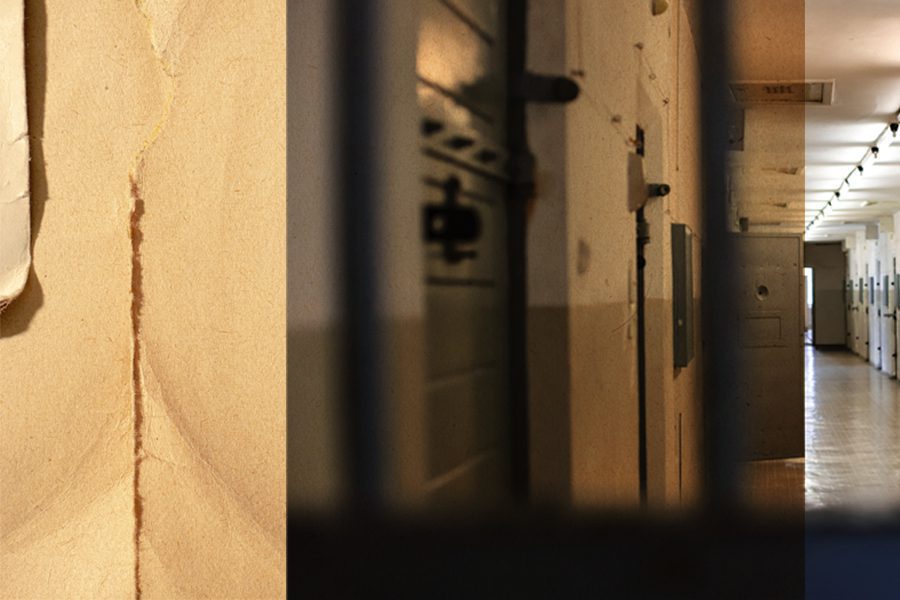

The lack of proper medical care in Russian penal colonies is one of the biggest problems that inmates face. Rustam Matsev says that the majority of complaints are connected with untimely and inadequate medical attention. This is confirmed by human rights activist German Urykiv, member of the public monitoring commission of the Kaliningrad region. He adds: “A person can get used to almost anything, but getting used to the absence of normal medical care is impossible”

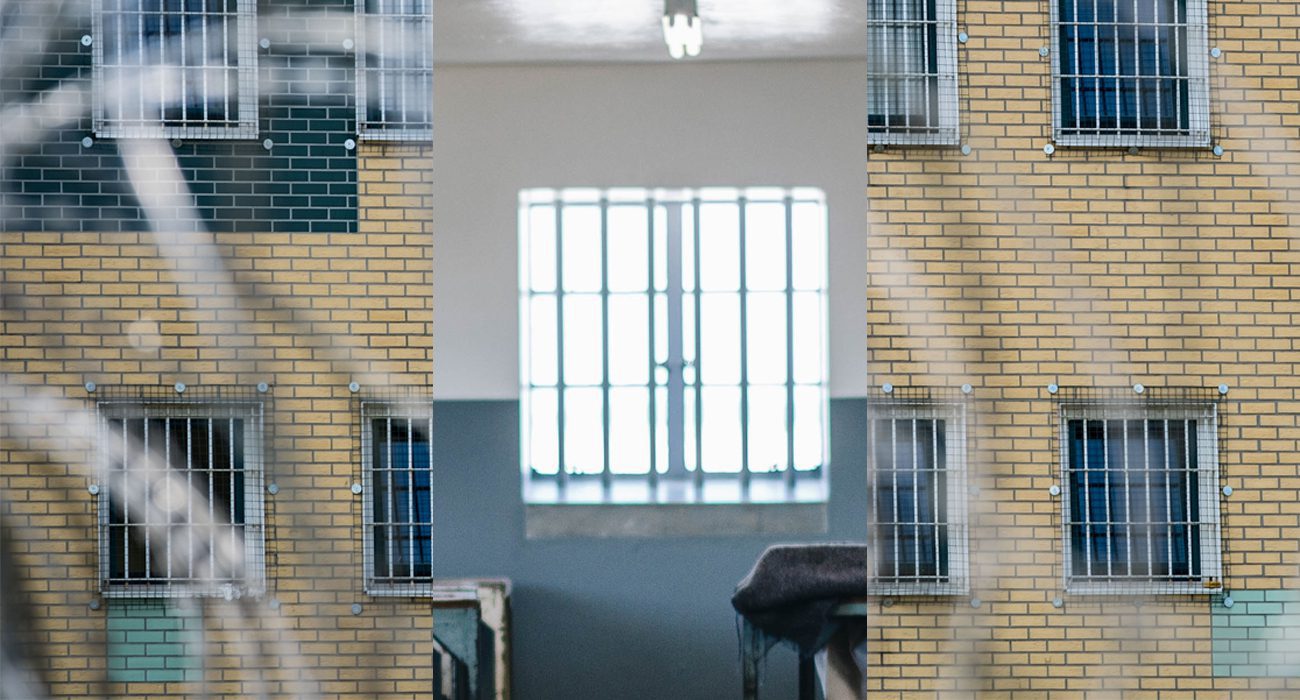

Annexation

The 37 year-old Ukrainian Ivan Fedirko has a rich criminal history spanning five convictions (for theft and bodily harm). In 2014, whilst Crimea was being annexed, Fedirko was serving time in a Crimean prison.

In March 2014, Fedirko reccounted how “a week went by [after the annexation] and that was it: people were singing Russian anthems, and different commissions arrived: strange people in astrakhan fur hats with shoulder marks on their jackets. They started to change the prisoners’ sentences. They just summoned me to the headquarters somewhere and said: we’re changing it [the sentence]. On what grounds? They answer: “Why are you trying to act so clever?” It doesn’t matter if I’m clever or not – I still want to know. Someone gets released, and the prisoners are happy. They don’t understand what is really going on. Some friendly Russian guys came and freed you. But you didn’t finish your sentence. If you go to Ukraine, you’ll just get locked up again.”

Fedirko was let out on time, but subsequently arrested again in Simferopol in 2015. He says that he “tried to live as best as [he] could”, but was detained for robbery and sentenced to 5 years. Later that year, Fedirko was transferred to the colony in Adygea. It was around then that he found out that he had become a Russian citizen. This is a normal situation for Crimean prisoners: unless they produce a written refusal, the majority have Russian citizenship forced upon them. For example, this is how Oleg Sentsov received his Russian citizenship, despite the fact that he publicly refused it.

Ukrainian human rights activists reported to Zaborona that during the annexation of Crimea there were 3400 prisoners on the peninsula, a large part of which had received a Russian passport against their will. After the annexation, a total of 47,000 were gradually transferred to Russia. These were people who had been detained after 2014 and had already served a sentence. An ex-employee of a Crimean prison told Zaborona in 2018 that the prisoners were transferred so as to avoid an uprising.

Such practice is prohibited by international law, inasmuch as Crimea is considered temporarily occupied territory. Ukraine does not recognize the issuing of Russian passports in Crimea and considers the prisoners there its own citizens. Russia, on the other hand, considers these prisoners its own citizens, and this is where the legal collision arises. Because of this, the prisoners do not return to Ukraine; since 2014 only 12 people have returned. For reference, all 373 prisoners who wanted to serve their sentence in Ukraine were returned from the self-proclaimed “Luhansk People’s Republic”. A portion of this group has already been released.

HIV

In Adygea, Fedirko met three other Crimeans: Andrey Titkovyy, Roman Zhurabovich, and Valeriy Makarovyy. Everyone except for Titkov had been transferred to Adygea at roughly the same time. Apart from Titkov, they were also all HIV-positive. Moreover, Makarov tells Rustam Matsev that he found out about his illness by chance, in 2017. He went half a year without antiretroviral therapy, since there was no infectious disease doctor in the penal colony.

Fedirko, in his own words, has hepatitis; this is why he was interested in the experience of the HIV-positive inmates. What’s more, he claims not to have received necessary medical care.

“They didn’t take my analyses or anything,” Fedirko says. “ I went to them more than once and said that my stomach was hurting. They didn’t give me any phosphalugel, even though they had it. They’re sort of indifferent”

Roman Zhurabovich is addicted to drugs. His medical card displays a wide range of illnesses: type 3 disability, hepatitis C, and HIV. Zhurabovich was arrested in Simferopol after the annexation in 2015. He was accused of distributing drugs on an “especially large scale”. Zhurabovich and his friends deny this: they say that although he used drugs, he did not sell them since he was not healthy enough. Zhurabovich was diagnosed with HIV in 1993. He has received antiretroviral therapy since 2001.

With regards to drugs, Russian legislation is heavy-handed. Article 282 (the illegal purchase and distribution of drugs) of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation is one of the most popular: one in four prisoners is imprisoned under it. In general, it is the drug users that are punished, not major drug dealers. Also methadone substitution therapy, during which a heroin addict is switched to methadone in order to reduce dependence on opiates, is prohibited in Russia.

Zhurabovich’s lawyers say that at the time of his transfer, there were officially no HIV-positive prisoners in the Adygea penal colony, although in fact there were about 80 people. Additionally, there was no infectious disease doctor in the colony at this time. He didn’t appear until 2018.

“They have therapy today, but not tomorrow,” recalls Fedirko. “That is, they do not consider that a person must receive therapy without interruption. They don’t understand that after every break, they need to change the whole treatment regimen. They hand out therapy as if it were aspirin.”

“They wrote that he [Zhurabovich] was a healthy person,” added Fedirko. “They also wrote that Titkov was healthy. We took him to the hospital because he couldn’t get there on his own – the man has lost thirty kilograms in weight. And they say to him: why did you come? Yesterday you were absolutely fine. “

Therapy without Therapy

Towards the start of 2019 there were 61.5 thousand inmates in Russian prisons. Of those with HIV, less than half received antiretroviral therapy. This is because the therapy is prescribed only to those whose number of CD-4 cells (the lymphocytes which are the first to kill infections and thus maintain immunity) falls below 350. These are outdated rules. The World Health Organization recommends prescribing therapy immediately after the detection of the disease and following any relevant bodily signs. However, most Russian prisons follow the old treatment regimens.

The Federal Penitentiary Service (FPS) of the Russian Federation argued that the number of HIV-positive people in penal colonies is decreasing, just as mortality rates are also decreasing. However, back in March 2016, Russia was the leader among European countries in prison mortality. There is no more recent data on how many people die in Russian penal colonies.

According to the Federal Penitentiary Service, over the last five years 696 people have died from HIV in Russian prisons. But as human rights activist German Urykov explains, most prisoners die not from HIV, but from concomitant diseases. Often the reason for this is lack of proper medical care.

“In some ways the situation is improving, in others it is getting worse,”says Urykov. “We recently managed to push through a new rule that states that a prisoner must be given bed rest when he starts taking antiretroviral therapy. This was necessary because there are different treatment regimens just as there can be different bodily reactions. Not all colonies have changed, of course – in some they have just stayed the same.”

The situation in Adygea is no exception. The fact that HIV-positive prisoners in different regions of Russia do not receive proper treatment was reported, for example, by the Russian branch of “Radio Liberty”. Rustam Matsev says that this is a systemic problem, which arises from both the isolated cases of corruption and greediness, as well as the more general defects in Russian medical care for prisoners. “A visiting commission carried out a large scale check in several regions, including Krasnodar. They checked the medical unit and discovered a lot of legal violations. The authorities themselves, in fact, admitted that this is a systemic problem,” says Matsev.

At the same time, German Urykov explains that generally there are no problems with the availability of therapy. Prisons are often well-stocked with medicine. Problems begin at the first appointment. Urykov says that “treatment regimens change frequently, and this is most likely related to what medicine the prison has purchased rather than [the prisoner’s] health”. “Diagnostics are carried out at the wrong time, for example, and when changing drugs, additional compatibility tests are not performed. As a result, prisoners often stop taking therapy because of side effects.”

The Crimeans

Roman Zhurabovich and Valeriy Makarov continue to serve their sentences in Adygea prison. Lawyers from “Legal Initiative” filed a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights because their clients are not receiving adequate medical care. Matsev is confident the ECHR will satisfy the claim.

Ivan Fedirko, having been freed, does not keep in touch with the other Crimeans. He lives and works near Kharkiv and says that he does not want to return to his old life. He recalls that in the Adygea prison he could not achieve fair treatment for the prisoners who had serious illnesses.

“Information from there [the Adygea penal colony] doesn’t get out, and it doesn’t get in, either. Some poor Tom, Dick, Harry, and a Crimean get sent to jail – who’s gonna stand up for them?”

With the support of Russian Language News Exchange. Translated by Johnny Skilling.