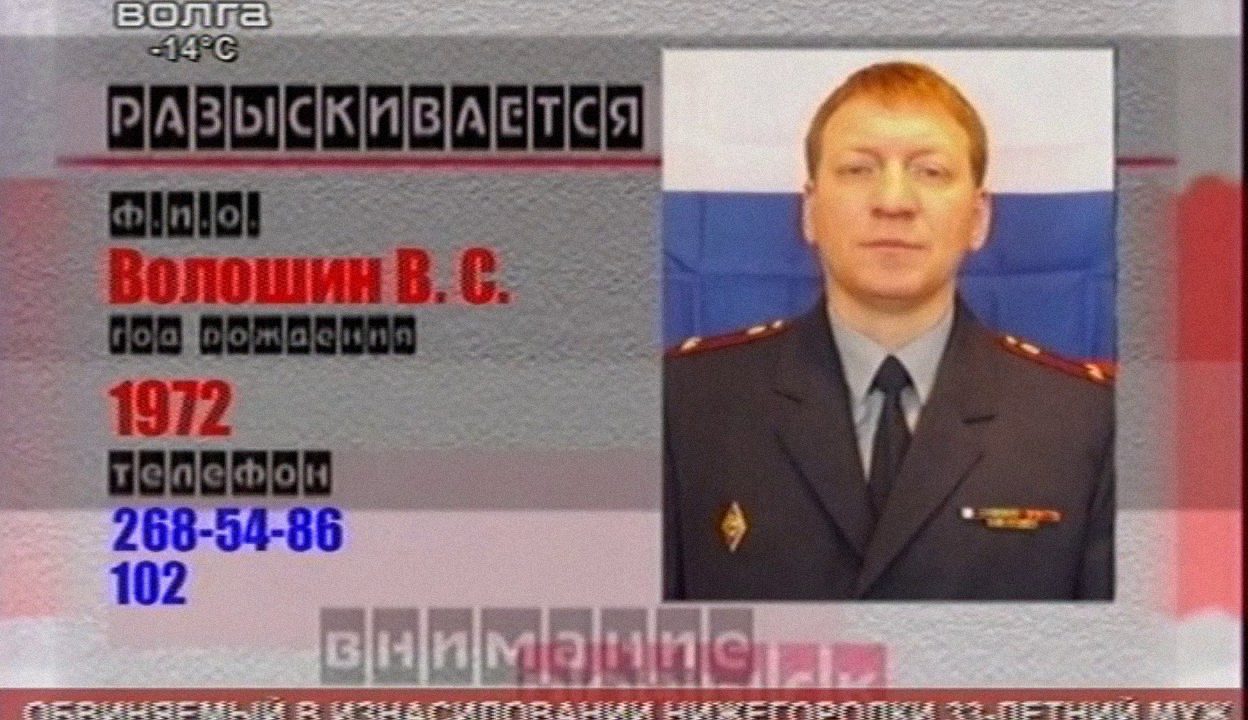

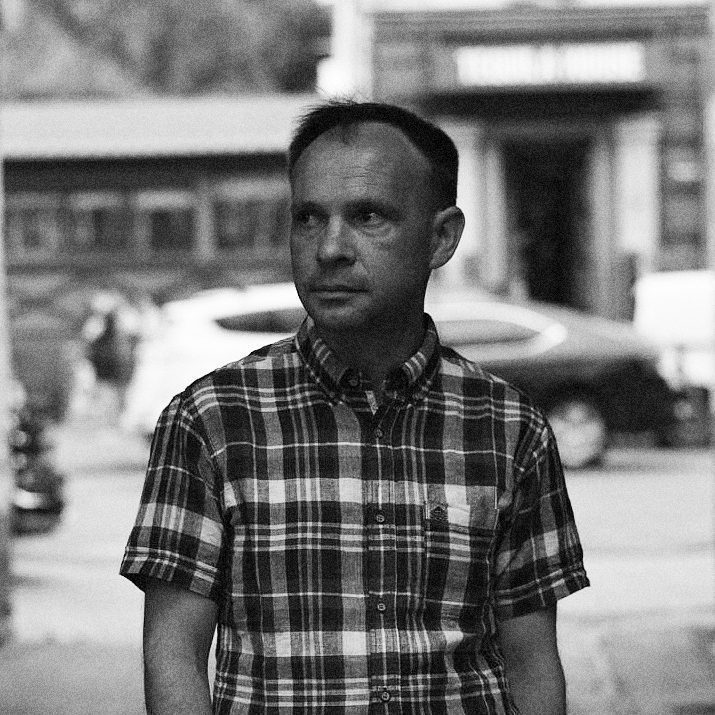

Russian human rights activists, convicts, and their families say that Corrective Colony No. 14 in Nizhegorodskaya Oblast, Russia, is a torture chamber. The man responsible: former colony superintendent Vasily Voloshin. In 2015, he was placed on an international most-wanted list — not for torture, but rather for minor financial crimes: illegally cutting down a forest and theft of prison property. Voloshin first hid in North Cyprus, then moved to Ukraine – where he was arrested. However, Zaborona has discovered that Voloshin was recently released from detention. He now lives in Kyiv and travels around the country at will.

Content Warning: This article contains descriptions of torture and other violence.

Winter, 2014. The prisoners of Russian Corrective Colony No. 14 in Nizhegorodskaya Oblast were preparing for dinner. They stood in the yard and waited to be let into the cafeteria. Suddenly, a group of prisoners emerged from the barracks. They were ‘activists’: an elite group with close ties to the administration. They carried another prisoner, Miraz Javoyan, to the infirmary. Half-conscious and wheezing, Javoyan wore only trousers. The rest of his body was covered in bruises. Worst of all were the bottoms of his feet: they had been beaten with shovel handles.

In the infirmary, the ‘activists’ turned on a video camera and tried to force Javoyan to confess that he had obtained the bruises by ‘falling’. To wake him up, they force-fed him sweetened coffee through a syringe. But he only mumbled disjointedly, and died soon after medics arrived. According to other prisoners, Javoyan had been beaten almost every day.

The order to coax a false confession out of Javoyan with the help of sweetened coffee was given by the colony’s superintendent, Vasily Voloshin. Russian human rights lawyers describe him as the architect of Colony 14’s violent regime, where prisoners were humiliated, beaten, mutilated, and even killed.

Voloshin’s Sons

As superintendent of Corrective Colony No. 14, Voloshin created a system where guards “kept their hands clean”: strict order was maintained by the prisoners themselves. Those chosen by the administration for this privilege were known as ‘activists’ or ‘Voloshin’s sons’. According to other prisoners, the ‘activists’ called Voloshin ‘pakhan’ — a prison slang term meaning ‘crime boss’ or ‘Godfather’.

Illustration: Yehor Hryb / Zaborona

“The activists were assigned concrete tasks. As a rule, they did not take the initiative themselves,” said Sergei Shunin, a lawyer with the Russian human rights organization Committee for the Prevention of Torture.

For prisoners, the ordeal began as soon as they arrived. They were forced to run everywhere with lowered heads and were subject to random beatings. In one room, said Shunin, there was a hook attached to the ceiling where they would hang prisoners like punching bags, head down, and beat them. The ones who were uncowed and showed character received special treatment: they were tied up with tape, beaten with sticks on the soles of their feet, and anally raped with shovel handles, mops, or rubber hoses. In prison slang, this is ‘opustit’, to be lowered, put down. It is considered the worst of all prison humiliations.

Prisoners were driven insane with pointless heavy labor: cleaning the same urinal over and over, scraping ice from the yard with a toothbrush, beating the ground with a heavy log all day to compact soil, carrying water from the first to the second floor only to pour it down the drain, working in teams of ten to haul carts or tractor trailers loaded with sand or rocks around the grounds.

Cases of torture and murder were written off as accidents. Evidence was faked and destroyed. For example, one convict working in the infirmary recalls being ordered by the administration to switch out an x-ray in 2013. The original had shown broken ribs, but the head of the Operational Department, Alexei Nichivoda, told him “not to show the doctors, switch out the x-ray, and bring the original to his office.” The patient died the next day.

Illustration: Yehor Hryb / Zaborona

Another case involved editing (in photoshop) pictures of a deceased inmate, Alexander Kalyakin. Voloshin used the doctored photos to bolster falsified documentation of the man’s cause of death, supposedly in an accident. But when he received his son’s body, Kalyakin’s father noticed numerous wounds, after which he turned to the Committee for the Prevention of Torture.

From 2011 to 2015, human rights activists received 184 complaints from convicts and their relatives. They detail torture, sexual violence, extortion, and psychological warfare at the hands of the ‘activists’, who acted on the orders of Vasili Voloshin or with his direct participation.

The Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia was satisfied with Voloshin’s results. Colony 14 was considered exemplary, “truly disciplined”, a model for others. Meanwhile, rights activists had been receiving messages of violence and torture for years, but had thus far failed to hold anyone to account: prisoners who complained were threatened until they recanted, and prison staff destroyed evidence. One ‘activist’ recounts an episode where, after yet another death, Voloshin watched video recordings of the battered prisoner’s last hours and then destroyed them.

Relatives of prisoners who suffered at Voloshin’s hands, alongside the Committee for the Prevention of Torture, even created a website to present the facts about his time in the colony and offer a reward for information leading to his location.

“That’s not even half of what they say about him.”

Vasily Voloshin is himself from Ukraine. He was born in the village Kuhaivtsi, ninety kilometers from Khmelnytskyi, a regional capital in the western half of central Ukraine. In 1989, he left, ending up thousands of miles away on a collective farm in Primorsky Krai, where he worked for about a month. The next year, he was drafted into the army.

Few people are left in Voloshin’s hometown who remember him as a young man. An elderly couple, living not far from the Voloshin family home, had little to say: yes, there was such a man, he left long ago. Why did he leave? Don’t know, don’t remember. They dismissed a version of the story where Voloshin, having created a scandal at home, was then obliged to run to the other end of the USSR. The Voloshin they recall was upright and hardworking. No one had ever said a bad word against him.

“I’m not going to tell you anything because I’m afraid,” said another neighbor of the Voloshins’. “We don’t talk about him here. Some are scared, some don’t know anything. Although people say lots of things among themselves, and I’ve read some stuff on the internet [about the accusations against him].”

Vasily’s mother, Maria Voloshyna, still lives in Kuhaivtsi, in a small home with a garden. She answered questions reluctantly. Voloshin, in her telling, was a good son who left to serve in the army. He then worked as a “lieutenant in a prison” and retired [Voloshin is now 49]. His bosses, she claimed, had wanted him to stay on.

“Do you know what crimes he is accused of?” I asked Maria.

“I know, of course I know. Bullshit — they’ll say anything. And that’s not even half of what they say about him.”

“What about torture? Have you heard anything? That people died because of him?”

“I don’t know. That didn’t happen, can’t have happened. If it had, they would have put him in jail. It’s not like he’s hiding in my pocket. He’s a free man. They say all sorts of bullshit. It’s all nonsense. They accuse him of murder. But if he were a murderer, he would be in jail.”

Maria declined to talk further, slamming the gate and retreating into the yard.

A criminal case for backgammon

While Voloshin was in charge of the colony, human rights activists continued to receive complaints until the Federal Penitentiary Service could no longer ignore them. Two criminal cases concerning the violent deaths of inmates were opened in fall 2015. Further cases were opened concerning extortion and rape.

Illustration: Yehor Hryb / Zaborona

Voloshin himself was removed from his position, and a criminal case was later opened — not for torture, but rather minor financial crimes. The warden was accused of “property theft and misuse of official powers.” According to investigators, he ordered prisoners to make furniture and other wooden objects for him: couches, armchairs, a child’s bed, backgammon sets, doors, bread boxes, and woodcuts. Voloshin removed these objects from the colony in summer 2015. One other criminal case against the ex-superintendent was opened concerning the illegal logging of 165 trees, “carried out by convicts on the orders of the administration.”

A site visit to the colony discovered a sauna and recreation area, neither of which were mentioned in official records, as well as forbidden computers, CDs, laptops, DVD players, and other devices. In the yard, there were unregistered knives, sticks with sharpened metal ends, and a barbecue with skewers.

When charges were announced, Voloshin fled to North Cyprus. Russia does not recognize the Turkish Republic of North Cyprus; consequently, there is no extradition treaty between them. Voloshin was placed on an international wanted list.

Screenshot from YouTube / Ivan Zhylcov

According to Sergei Shunin from the Committee for the Prevention of Torture, Voloshin lived reasonably well on Cyprus. He applied for residency, reunited with his wife and two young children, and occupied himself with a business formally registered to a third party. He also allegedly received income from real estates formerly belonging to Colony 14. The properties had been reregistered to Voloshin by loyal real estate agencies. Rights activists learned of this from the scheme’s victims, who were forced to give up their homes or move to more modest apartments.

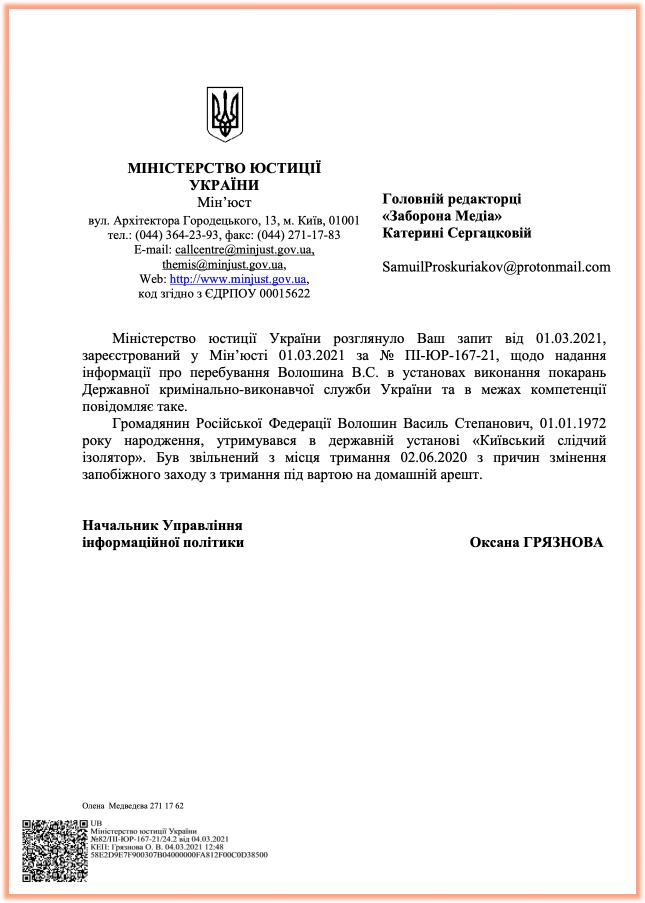

For some reason, Voloshin decided to leave North Cyprus for Ukraine, where he was detained in March 2020 in a joint operation by Interpol, the North Cyprus police, and Ukraine. He was placed in the Lukyanivska pre-trial detention facility and held in unusual comfort, as can be seen in this video about VIP cells in Ukrainian isolation facilities. Voloshin appears at 0:04 and speaks briefly. Justice Ministry officials confirmed to Zaborona that Voloshin was in fact held in the Lukyanivska facility.

Russia demanded the former warden’s extradition. However, as we learned from court documents, Voloshin’s defense claimed that he was being pursued for political reasons. Supposedly, Voloshin had been offered Russian citizenship in 2014, when Russian aggression against Ukraine began. He refused, fell into disgrace, and fled. However, Voloshin already had Russian citizenship when he worked in the colony. A Russian passport confirming citizenship was discovered on his person when he was arrested in Kyiv. This was enough to dissuade the court from accepting his version of events. Sergei Shunin does not discount the possibility that Voloshin arrived in Kyiv specifically in order to change his citizenship. In that case, extradition would no longer have posed a threat.

No house arrest

Voloshin was remanded to house arrest in March, but his term ended in August 2020. Beyond that, silence: no further actions or decisions are recorded in court documents. As far as Zaborona was able to determine, Voloshin now moves freely around the country. At the beginning of April, according to his mother and a neighbor, he visited Kuhaivtsi for a nephew’s funeral. A few days later, according to the same neighbor, the Voloshins left for Khmelnytskyi to attend Vasily’s sister’s wedding. Now, says Maria Voloshyna, her son lives in Kyiv, where he works. She will not specify where. Also in Kyiv are Voloshin’s wife and children.

Lawyer Oleksiy Skorbach told Zaborona that Ukrainian authorities may close the criminal case against Voloshin.

“He is accused not of torture and murder, but rather petty crimes. For that reason it seems likely that, when the statutory period expired, Voloshin was released from house arrest and will almost certainly receive a Ukrainian passport in accordance with Article 8 of the Ukraine Civil Codex, ‘On Ukrainian Citizenship’. His lawyers noted in court that he is by birth Ukrainian, his relatives live here, and he has contacted Ukrainian Migration Services concerning an application for citizenship.”

Oleksiy Skorbach

Zaborona has sent requests for information to the offices of the Prosecutors General of both Ukraine and the Russian Federation in order to clarify whether the statute of limitations regarding Vasily Voloshin’s crimes has truly expired, and on what basis Ukrainian prosecutors refused extradition. We have yet to receive an answer. The Ukrainian Ministry of Internal Affairs refused to provide the requested information, citing the case’s active nature, as well as the law “On the protection of personal data”.

Produced with the support of Russian Language News Exchange

Translated by Hallie Sala from Respond Crisis Translation