DNA is being edited in Ukraine. Zaborona explains what CRISPR is and how it both helps and threatens humanity

Ukraine is one of the most popular countries in the world for eco-fertilization and one of the few countries where it is not forbidden to edit the genetic code. Often these two procedures are done together. Some scientists believe that editing DNA is a good thing, while others worry that technology can be used by dictators to create a “superhuman.” Zaborona explains what CRISPR-cas9 is and why it’s time to start a public debate on the ethics of its use.

How DNA is arranged

There are deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecules in the nucleus of our cells. DNA is a database where our genetic information is stored. This is something like instructions for building our body to the infinitesimal detail. The DNA strand consists of nucleotide units. A gene is a piece of DNA with a specific nucleotide sequence. The set of human genes is a genome consisting of 46 chromosomes. If we imagine that the genome is a very long text, and the nucleotides are letters, then the gene is a small part of the text, a complete statement.

For example, a gene encoding insulin production consists of 60 nucleotide pairs. To take information from the “database”, a special enzyme creates ribonucleic acid (RNA) in the cell nucleus, which copies the necessary genetic “instructions” from DNA. Then the RNA leaves the nucleus, and the synthesis of the necessary proteins begins. Yes, in the simplified version, this is how the key mechanism of our life occurs.

In addition to genes in DNA, there are so-called “non-coding sequences”, which do not contain any instructions or information. Some of them perform various procedural and technical functions, but the role of most of these “statements” remains unknown.

What is CRISPR?

In 1987, Japanese scientists were studying the DNA of Escherichia coli, a common intestinal strain that causes an acute infection. They were surprised to discover a “non-coding sequence” that only humans have. Bacteria usually have a simpler and “laconic” strand of DNA. The detected sequences looked strange — repetitive segments which were separated by different sections. These areas were called spacers.

Spanish scientist Francisco Mohica described these sequences as such: “Short palindrome repetitions, regularly arranged in groups.” It came to be known as CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) was released. In 2002, it was discovered that these “repeats” were accompanied by specific Cas proteins. However, for a long time no one could understand what that meant.

The breakthrough came in 2005, when several laboratories decided to compare the enigmatic CRISPR with already known DNA sequences. It was found to match the DNA of some bacteriophages — viruses that infect bacteria — and that CRISPR is a bacterial immune system with a clear system of teamwork. Spacers in the CRISPR sequence are DNA fragments of viruses familiar to the cell, something like a data folder. When a virus invades, a guide is formed — an RNA molecule that carries in itself information about viruses and, together with Cas proteins, performs the function of finding and destroying them. The Cas-protein carefully “cuts” the DNA sequence of the virus, thus killing two birds with one stone — it destroys the virus and, at the same time, collects new spacers, if necessary. This battle can be endless, however. Viruses mutate, and the CRISPR RNA from proteins can stop recognizing them. In addition, spacers with data on viruses that have not attacked the cell for a long time are subsequently erased from the DNA.

The Cas9 Protein

CRISPR systems are different. In some, stages of the “special operation” are responsible for individual Cas-proteins, which form a complex system. And there is, for example, the Cas9 protein: in this case, all the work is undertaken by one powerful protein. It became the subject of research which by 2012 had shown that the immune mechanism of bacteria could edit the human genome.

The editing happens as follows: in the laboratory, CRISPR RNA is created with the required spacer. The Cas9 protein binds to this RNA, cutting out the necessary (or “problematic”) DNA fragment. And instead of the DNA fragment, the virus can encode any other, such as a defective part of the genome that causes a genetic disease. There are some ways to prompt the body how to “stitch” a strand of DNA without a defect. Our DNA is arranged as such: if it lacks something, it copies it from the next cell, and in the next it is possible to “enclose” what is necessary.

This discovery made it clear that by editing the genome, you can “cut out” many genetic diseases. For example, in May 2020, the American pharmaceutical company Editas Medicine reported that it had used CRISPR / Cas9 to cure a form of congenital blindness. In the past, scientists took human cells and “cut” them with the help of proteins in a test tube, and then returned the altered cells to the body, but in the case of blindness, the solution was injected into the patient’s eye.

However, man has not yet explored the full nature of genes. We do not know what most genes are responsible for, and even if we do, we do not always understand their significance. Some diseases are monogenic, that is, they are caused by a change in only one gene. But the genetic nature of some diseases, such as schizophrenia, is currently unclear, as they can be caused by a complex combination of genes. Suppose one gene, located in the upper layers of the epidermis, is responsible for the fact that the skin of a person is overly sensitive to the sun. At the same time, we do not know what that same gene is responsible for in, say, bone tissue. Trying to rid a person of skin disease could make them unable to walk.

In addition, there is a possibility that Cas9 can cut not only what is needed, but also some similar “sequences”. The problem of unwanted mutations that can occur during the “stitching” of the DNA chain has not been completely resolved.

“Designer” children

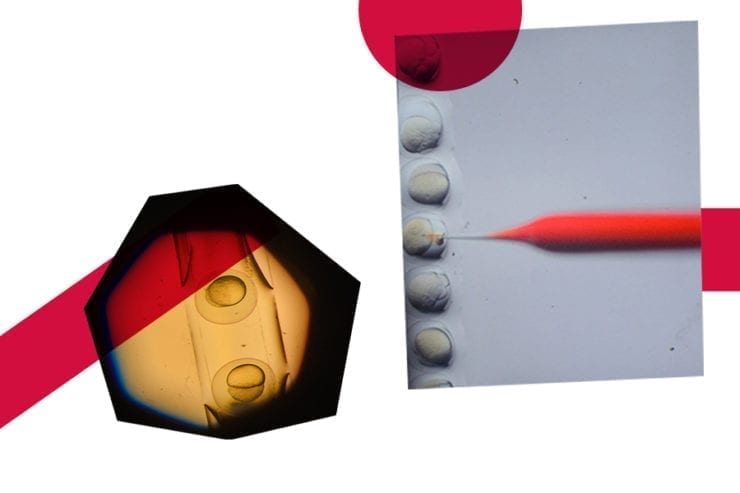

Changes in genes are easiest to carry out in a fertilized egg, when the future person consists of only one cell. The first such experiment was conducted in 2015 in China: with the help of CRISPR / Cas9, researchers tried to cure the egg of a genetic error that caused the disease Beta-thalassemia. They did not dare to do it to a full-fledged person; the experiment was completed at a certain stage of cell development and division. It was not very successful: first, it turned out that only 5–10% of the cells did not contain a defective gene, and secondly, the system made many unplanned changes in the genome. It was necessary to increase accuracy.

Scientists from different countries now claim that they can increase the accuracy of CRISPR and avoid unwanted mutations. Moreover, in addition to Cas9, there are other bacterial proteins that can “cut” DNA. It is known that there are clinics (in most countries they operate underground or semi-legally) that edit DNA in embryos to, for example, have children with certain eye and hair colors.

Embryos have only recently begun to be edited. The most famous story took place in China. In 2018, world-renowned geneticist He Jiankui said that his experiments with CRISPR gave birth to twins with immunity to HIV. However, it turned out that, firstly, no one had given him permission to conduct such experiments. The management of the University of Shenzhen did not know anything about them. Secondly, he had shown false documents to the pregnant women who were part of the study. And thirdly, there is no exact data to prove that the experiment was successful. In December 2019, He Jiankui was imprisoned following an investigation.

Dreams of a superman can become reality

Much less is known about embryo editing procedures in Ukraine. For example, in the summer of 2018, the Nadiya clinic told the American radio station NPR that scientists had managed to create a child with the help of DNA from three different parents for an infertile mother. And from the documentary “Unnatural Selection”, dedicated to DNA editing (released on Netflix in 2019), it became known that this was done using CRISPR. Journalists have also reported that the clinic employs Chinese scientists who are being persecuted by the Chinese authorities for their participation in similar experiments. In an interview, the clinic director Valery Zukin said, “If you can help families have children, then why should it be banned?”

In the West, this issue is accompanied by loud discussions, but in the post-Soviet space, this topic is hardly discussed in public.

“If we intervene [in human DNA] only to prevent hereditary diseases, such as hemophilia, then it is a good thing,” believes Oksana Piven, a senior researcher at the Institute of Molecular Biology and Genetics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. “But if we just want to introduce gene variants that will make a person stronger and program him to become a good astronaut, or something along these lines, then how is this ethical? It limits the equality of all people…”

Meanwhile, politicians in countries with authoritarian regimes are increasingly talking about the use of CRISPR for military purposes.

“A person can create a person with any given characteristics. He can be a genius mathematician, he can be a musician, but he can also be a military man — a man who can fight without fear and pity and compassion, and without pain,” said Russian President Vladimir Putin during the World Festival of Youth and Students in October 2017. At the same time, he said that genome editing is a weapon that is “scarier than an atomic bomb.”

And during a government meeting on the development of genetic technology in Russia, it became known that the Russians have already developed the CRISPR protein Cas13a — it is even cheaper and more accurate than Cas9.

Currently, there is no international document, such as a convention, that could formulate the principles of ethics of gene editing and regulate this process. Cas9 protein is very simple, says geneticist Oksana Piven, and there are no special permits for the purchase of reagents needed for the gene editing procedure in a laboratory. In most countries, this procedure is prohibited by law, but Ukraine and Albania are two countries in Europe where there is no direct ban.

Listen to our podcast about CRISPR: host Roman Stepanovych discusses with scientists how this technology can change our lives, and why there is so much controversy surrounding its ethics.

This story is produced with the support of the Russian Language News Exchange.

Translated by Kate Garcia