In late 2020, the world was shocked when French history teacher Samuel Paty was beheaded right in front of metro passengers. The murderer turned out to be a Chechen citizen who had been granted asylum in France. Since then, dozens of migrants from the North Caucasus who came to Europe to escape Russian Intelligence services have been arrested and are now being threatened with deportation to their homeland, where they would likely face arrest, torture, or extrajudicial execution. Zaborona’s Editor-In-Chief Kateryna Sergatskova spoke with one migrant who was tortured by the Russian authorities — and who now faces deportation to Russia.

One day, in a lesson dedicated to free speech, history teacher Samuel Paty decided to show his students some caricatures of the prophet Muhammed that had previously been published in the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo. Soon after, on October 16, 2020, Paty was attacked by a young man wielding a kitchen knife. The man cried “Allah Akbar” and beheaded Paty. The attacker was later shot and killed by police. He turned out to be an 18-year-old from Chechnya who had been granted political asylum in France in 2008.

French President Emmanuel macron called the murder “an Islamic terrorist attack,” and a wave of Islamophobia swept across the country. Several days after the attack, Mohammed Gadayev, a 36-year-old Chechen asylum-seeker in France, was arrested.

“They told me I was a threat to France,” said Gadayev.

Gadayev and I spoke by telephone; he’s currently located in a Paris detention facility where asylum seekers and undocumented migrants are held. He’s been there since October 2020. The French government is preparing to deport him back to Russia, where he was tortured before escaping in 2010. Gadayev has seven children — most of them are currently with his wife, who is also being threatened with deportation.

Riot police basement

Mohammed Gadayev fought on the side of the Chechen separatists in the Second Chechen War. It’s no surprise, then, that Russian authorities have been pursuing him for almost half of his life.

The Second Chechen War was the first major step taken by Vladimir Putin after becoming president. He threw thousands of Russian soldiers into Chechnya in order to ensure the subjugation of the Chechen Republic, which had declared independence from the federal Russian authorities in 1991, to Moscow. Over the course of the war, the majority of Chechen towns were literally wiped out — tens of thousands of civilians were killed.

Gadayev was first arrested in 2004, that time by Chechens who had defected to the side of the then President of the Chechen Republic, Akhmat Kadyrov. It was a common occurrence during the second military campaign: Chechens who had formerly fought against Russia were enticed or threatened into joining pro-Russian forces earning the nickname “Kadyrovtsy.” They often agreed to cross over due to press both on them and their loved ones. According to Gadayev, it was Kadyrovtsy who assaulted him and demanded that he join their cause. He managed to escape to Kazakhstan, but he was put on Russia’s federal fugitives list, and in 2006 he was deported back to Chechnya.

Gadayev spent almost three years in prison for participating in the war on the separatists’ side. He was released in the middle of October 2009, but on November 1, they arrested him again. He was put in an unofficial prison on a Chechen Special Forces base — ”in the basement,” as he described it. There, his captors beat him with a bat and with a gun handle, chained him to a radiator, and threatened to kill him, “take him to a swamp,” and “bury him.” The torture lasted five months, and none of his relatives knew was he was. Gadayev claims that the main person responsible for his torture was Alikhan Tsakayev, the head of the Chechen Special Forces, who grew up in the same village as Kadyrov.

At one point during his detainment, Gadayev saw three young men brought into the basement, where two of them were subsequently killed. In December 2009, Islam Umarpashayev was brought to the basement. His arrest was the center of a scandal; his father applied to the European Court of Human Rights, and the case was taken up by Igor Kalyapin, the head of the Committee Against Torture. As a result, both Umarpashayev and Gadayev were released.

When Gadayev was leaving the basement, the officers told him that if he told anyone where he had been kept, they would kill his parents. In the spring of 2010, he left Chechnya for Moscow, and from there he went to Poland.

Special witness

In Poland, Gadayev was granted asylum and agreed to become a special witness in the case of Islam Umarpashayev’s torture — ”after all, we were the only two people to get out of the basement alive,” he said. The Committee Against Torture convinced him to testify against the Chechen Special Forces to the Russian investigative committee on European territory. The main suspect in the torture case was Alikhan Tsakayev.

Special Forces officers soon began calling Gadayev on Skype to threaten him. In Chechnya, they went to Gadayev’s father and told him they would kill Gadayev if he didn’t stop him. After that, Gadayev went to the prosecutor’s office in Poland and asked to be allowed to testify in the torture case. The result was an unusual procedure that required a Russian investigator to come to Europe to record the testimony. And, according to Igor Kalyapin, because Gadayev had been granted asylum status because he was in hiding from the Russian justice system, it was difficult to convince the prosecutor of the procedure’s necessity. Gadayev would require security during the testimony.

The Polish police determined that there wasn’t sufficient evidence to provide him with security, and the request to allow him to testify was refused.

After that, Gadayev went to France, and in 2014, he requested that the French authorities allow him to testify against Chechen Special Forces. After numerous attempts by human rights defenders, he was finally granted permission. Then-Chief Special Investigator for the North Caucasus Igor Sobol (who was fired in 2019 and it currently tried to regain his position) traveled to France to question Gadayev. It was Gadayev’s testimony that formed the case’s basis — one of Russia’s most high-profile torture cases. However, the investigation never reached the court, and was closed last year, according to Kalyapin.

Gadayev’s story took a strange turn from there. In 2015, soon after the terrorist attack on French magazine Charlie Hebdo, French Special Forces burst into Gadayev’s home and accused him of concealing one of his wife’s relatives who had come to France under a counterfeit visa and been granted asylum. Additionally, he was accused of “being a revolutionary in Chechnya,” which allegedly made him a security threat to France. The French government had obtained the information about Gadaev being a dangerous “Islamist” and “terrorist” from their colleagues in the Russian FSB.

Then, on a trip to Poland in 2017, Gadayev was stopped by Polish officials in the airport and offered an ultimatum.

“They wanted me to tell them who was transporting people across the border from Poland to Germany,” said Gadayev. “I told them it didn’t concern me. In retaliation, they opened a case against me for not living in Poland [as refugees are supposed to] and revoked my status.”

The official reason

Gadayev tried to get asylum in France, but the judge refused, since he still had Polish documents — despite the fact that they had been annulled. In 2019, the French authorities suddenly put him on house arrest for violating migration law. The government was simultaneously refusing to give him documents because he already had Polish ones and accusing him of being in France illegally because he didn’t have Polish documents.

“They put Russia as my return country,” Gadayev said. “So I took it to court, and the court decided that I definitely couldn’t be [sent] to Russia. Even the European Court of Human Rights told the authorities that I couldn’t be deported. I applied for asylum again, this time on the basis that France itself had acknowledged the threat and acknowledged that I didn’t have Polish documents. A year and a half had passed already, and they said that I was a threat to France. They had even bought me a ticket to Moscow, but the court interfered in time.”

Igor Kalyapin, the head of the Committee Against Torture, claims that President Ramzan Kadyrov himself has been informed about Umarpashayeva’s case and the role that Gadayev played in testifying against the Chechen Special Forces officers.

“Their issues with Gadayev are on a high level,” said Kalyapin. “I have no doubt that they’ll finish him off if he ends up in Russia.”

A blood feud

In August 2019, Chechen citizen Zelimkhan Khangoshvili was killed in the center of Berlin. He had fought alongside Chechen separatists and was close to the leaders of the Republic of Ichkeria and the underground “Caucasus Emirate.” Khangoshvili lived in Georgia until 2014, when he moved to Ukraine. He escaped several murder attempts, and at the end of 2015, after yet another such attempt, he went to Germany in hopes of getting political asylum. But when Khangoshvili was walking in a park, he was shot by a man on a bicycle. The man was soon detained by German Special Forces, and turned out to be an FSB employee.

After Khangoshvili’s murder, his wife was granted political asylum. His nephews who tried to get asylum in Sweden, however, were deported to Georgia, according to multiple sources who work in an organization involved in their protection.

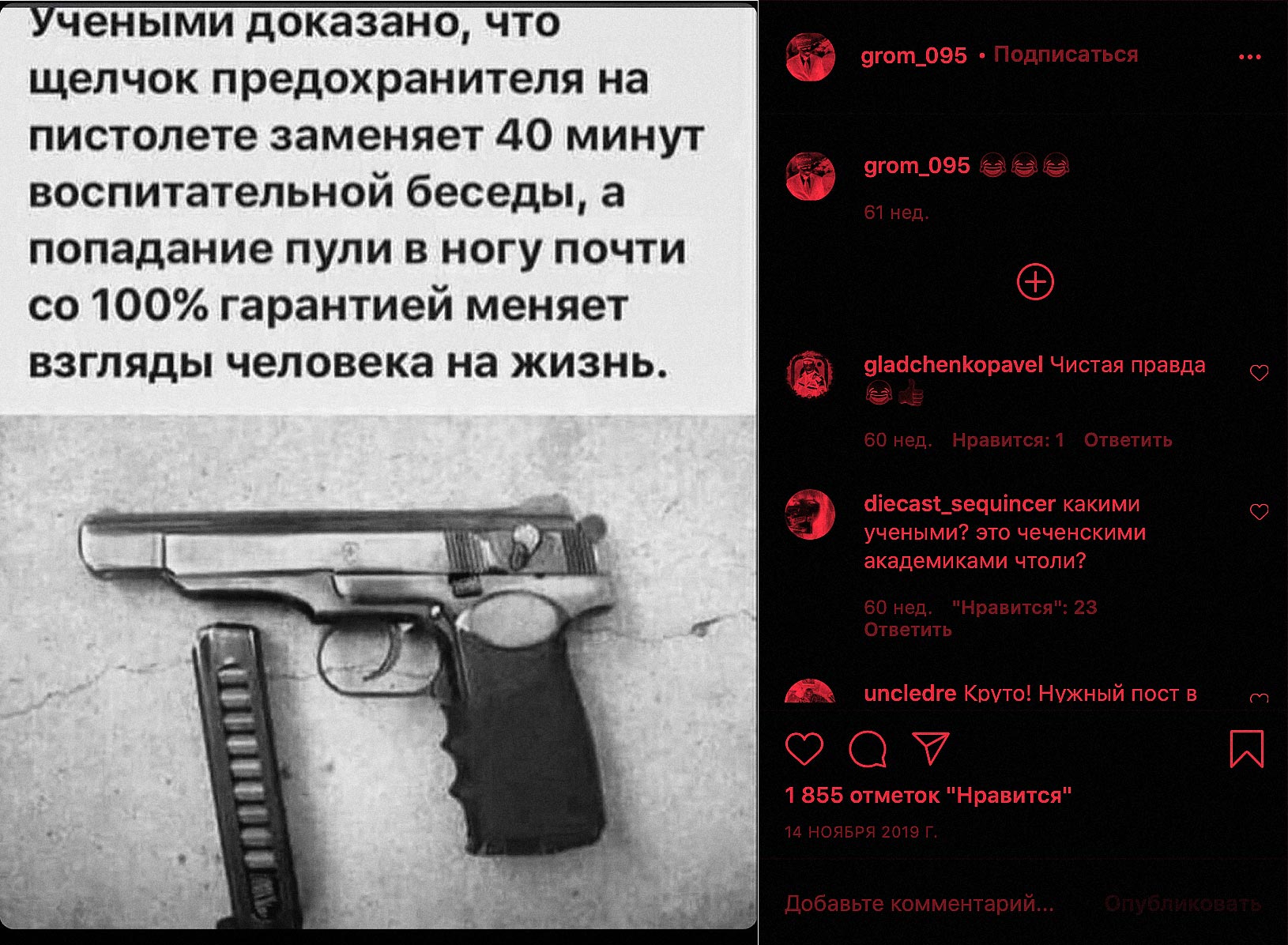

On February 26, 2020, an unknown person broke into Chechen opposition blogger Tumso Abdurakhmanov’s apartment and hit him several times with a hammer while he was asleep. Abdurakhmanov managed to hit his attacker back and call the police. He believes the murder attempt was organized in response to him calling Chechen president Akhmat Kadyrov a traitor to the people. In Russia, a case was opened against Abdurakhmanov for participating in the war in Syria, but the stamps in his passport prove that he was in Kazakhstan at the time.

In July 2020, a Chechen man named Mamikhan Umarov, also known as “Anzor,” was killed in Vienna while waiting to receive asylum. He was active on social media, and often talked about how the Russian authorities were organizing murder attempts against political opponents and former Chechen fighters in Europe.

Nevertheless, in the countries in Europe where the majority of refugees from Chechnya live — France, Germany, Poland, and Austria — there’s not enough data to prove that the Russian government is keeping track of Chechens who don’t support its policies.

Soon after the Chechen immigrant attacked the teacher, the French government announced their intentions to deport 231 “alleged extremists.” According to the media, the head of the French police department Gérald Darmanin gave this order to local authorities.

According to Alexey Obolenyets, a lawyer at the Swedish human rights organization Vayfont who currently lives in Ukraine and specializes in politically-motivated cases against immigrants from the North Caucasus, more than a thousand deportation cases and several dozen extradition cases related to migrants from the North Caucasus are currently being considered in Europe right now. Fifty people facing deportation from Europe to the North Caucasus have reached out to Vayfond.

“We can talk about hundreds or even thousands of several thousands of people who are facing deportation,” Obolenyets told Zaborona. “This usually happens because Russia either opens cases against these people and demands their extradition, or provides other countries’ intelligence agencies with information about how these people are supposedly security threats.”

According to Obolenyets, another wave of problems for Chechen refugees began in about 2017 — after the Islamic State started losing ground in the Middle East. Authorities in Europe, Turkey, and the Middle East began mass arrests of people who allegedly participated in illegal terrorist actions in Syria and Iraq. But at the same time, according to Obolenyets, “for every Russian who was actually in Syria, there are about five people who weren’t there but were accused of being there by Russia.”

Colonial idea

The Russian government is conducting a preliminary investigation and has initiated thousands of criminal cases against people from the North Caucasus. The majority of the cases are based on the “terrorism” and “extremism” articles of the Criminal Code. According to lawyer Alexey Obolenyets, there are three main reasons.

“Either a person moved to Europe a long time ago and is now trying to obtain legal status, or he already was granted asylum, and he’s being offered cooperation from Russia, including from Chechnya. The person refuses, and he’s put on a ‘Most Wanted’ list — they threaten him with extradition and up to 20 years in prison,” he said. “Or there’s a plan for solving terrorist cases that Russian authorities are carrying out in the North Caucasus. That would be the only way to explain the tightening of punishments, the increase in sentence lengths, and the strengthening of authoritarian power that’s occurred as a result. It’s important to talk separately about critics of the regime, bloggers and human rights activists, and religious leaders. The percentage of them isn’t so high, but it’s their cases that are becoming systemically important; cases against other refugees are lining up around these ones.”

According to Obolenyets, the majority of false accusations against refugees from the North Caucasus are based on witness testimonies. One of his clients, for example, was accused of financing the Islamic State. The client was a refugee in Germany who was contacted by people from Chechnya, lured to South Ossetia (the Georgian Republic currently occupied by Russia), and detained there. After that, he was kept in a detention facility in Grozny, where he confessed to financially supporting the Islamic State and gave the names of 25 accomplices. In court, he claimed that he had been tortured, but he was sentenced to nine years in prison. Additionally, Special Forces opened up cases against each of the people he mentioned, and sent extradition requests to Germany and Ukraine.

“Authorities [of EU countries and Ukraine] respond to these requests,” said Obolenyets. “Meaning that based on false pretenses from Russia, real actions are taken to arrest and extradite people. While most of these people fled Russia for serious reasons, they became victims or witnesses of torture or Special Forces’ crimes.”

For example, in the fall of 2018, Ukraine extradited Timur Tumgoyev, an Ingush refugee who fought for the Ukrainian-Chechen Sheik Mansour Battalion, at Russia’s request. In Russia, a case was opened against him for allegedly participating in military operations in Syria on the side of the Islamic State. It soon came out that while he was in a Russian prison, he was subjected to torture. And in December 2020, the Ukrainian authorities extradited Ingush Ruslan Akiev, a member of the same battalion, to Moldova under a simplified procedure. It was Russia who demanded his extradition.

According to Obolenyets, the purpose of this policy of fabricating criminal cases is “to protect the colonies from leaving their mother country.”

Since the events of 1994 [the beginning of the First Chechen War], after all the bombing of Chechnya, the Caucasus has largely been held by an impressive number of military and police structures,” said Obolenyets. “Actions related to the persecution of natives of the North Caucasus are aimed, among other things, at keeping the territories that can be called post- colonies under their control. It’s the realization of a so-called postcolonial policy, which serves to continue Tsarist Russia’s imperial policy. That’s why people are kept in constant fear. This is one of the methods of psychological destruction that has little to do with the fight against terrorism.”

Translated by Sam Breazeale from Respond Crisis Translation