A year and a half ago, Ukrainian writer Haska Shyyan wrote the novel Behind Their Backs, for which she received the EU Literary Prize. In October, the novel received another award, the Book Pitch-2020 project at the OIFF. After that, she began to be heavily criticized because of the apolitical nature of the main character and the novel’s naturalistic scenes. Exclusively for Zaborona, journalist Maria Blindyuk spoke with Haska Shyyan about patriotism and the sexual revolution and explained why fiction should not meet the reader’s demands, no matter how much we demand it.

A frozen Galician youth

Haska Shyyan grew up in Lviv during the time when Austro-Hungarian mythology was just beginning to be sewn into the city’s mentality. The nineties in Lviv were the time of the Ukrainian rock band “Dead Rooster”, the literary performance group “Bu-Ba-Bu” and the legendary art space “Dzyga” — underground sensations which became massively popular. Everyone wanted to join in on the fun, at least for a little while. At the same time, being creative back then was equal to being poor. This is how many private companies appeared — people started businesses not because they were ambitious but because they were in a chaotic search of income.

“Sometimes I joke that I froze my crazy youth like ovaries and then thawed it”, says Haska. She recalls that she spent her youth in the reality of the conformist and measured Galician system. Together with her sister, she started a small textbook business. She graduated with a degree in classical philology. She had a long relationship with one partner. The only thing that escaped her was an early pregnancy, although it was a fairly recognizable scenario for that generation of women.

The age of twenty-seven marks a turning point in many people’s lives, and Haska’s was no different — she eventually started earning more money, decided to try to study literature, and traveled almost continuously for two or three years. The early aughts were the era of LiveJournal, so Haska began to write what would today be considered a travel blog and tried writing poetry. She was soon asked to translate the Booker Prize-winning author DBC Pierre’s book, Lights Out in Wonderland, a project that helped her overcome imposter syndrome and eventually prompted her to write her debut book.

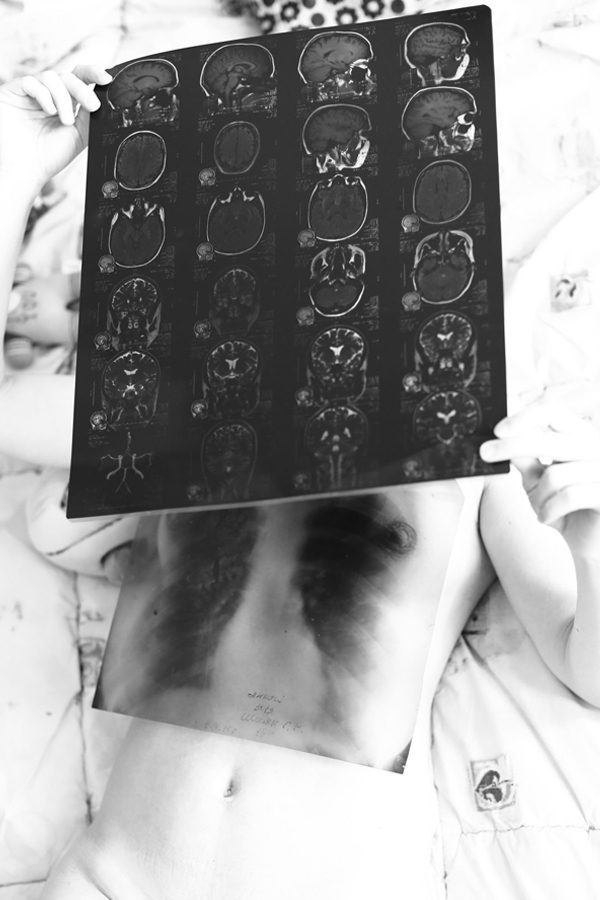

Almost immediately after the translation’s publication, Shyyan learned that she was pregnant. “It was a desirable pregnancy which did not meet all of society’s standards. I had planned to be an independent mother. That was my choice. Then I was thrown into the cocoon of a sedative state where nothing mattered and nothing worried me. When my daughter was 11 months old, my physical and emotional exhaustion landed me in the hospital with meningitis”.

Meningitis literally screws the patient to the bed — you can not raise your head for ten days. To at least have some fun between the daily drip sessions, Haska listened to the neighbors’ conversations from the sterile boxes and imagined stories that later became long posts on Facebook. Coupling them with a file of freaks collected during her CouchSurfing days, an absurd flow of consciousness, and a reflection on neurosis in the spring of 2014, Haska Shyyan published her first novel Hunt, Doctor, Hunt.

Soon the plot of a second novel began to materialize. “I understood that there would be a girl whose boyfriend was going to the army. A woman is not as patriotic as her husband. In this scenario of stagnant relations, a strong external factor appears, shaking everything up. And these two do not know what to do”.

Behind Their Backs

The plot of the novel Behind Their Backs is taken from Ukraine’s current reality. The main character Marta’s boyfriend is mobilized to the combat zone in Donbas. Marta doesn’t understand him. She thinks he could have tried to get out of enlistment so as not to leave her alone. She is offended, sad, angry, masturbating, lost in thought. For the author herself, this is a book about the crisis of relations, searching for an island of security and protection in the world, and liberation. “A person is born to find themselves in certain socio-political circumstances, and they may be comfortable in them or not. It is unrealistic to portray a society without a political context. The world around us is freaky, surreal, and absurd enough as it is. There’s no need to invent dragons and unicorns in it. Hyperrealism is essential to me”.

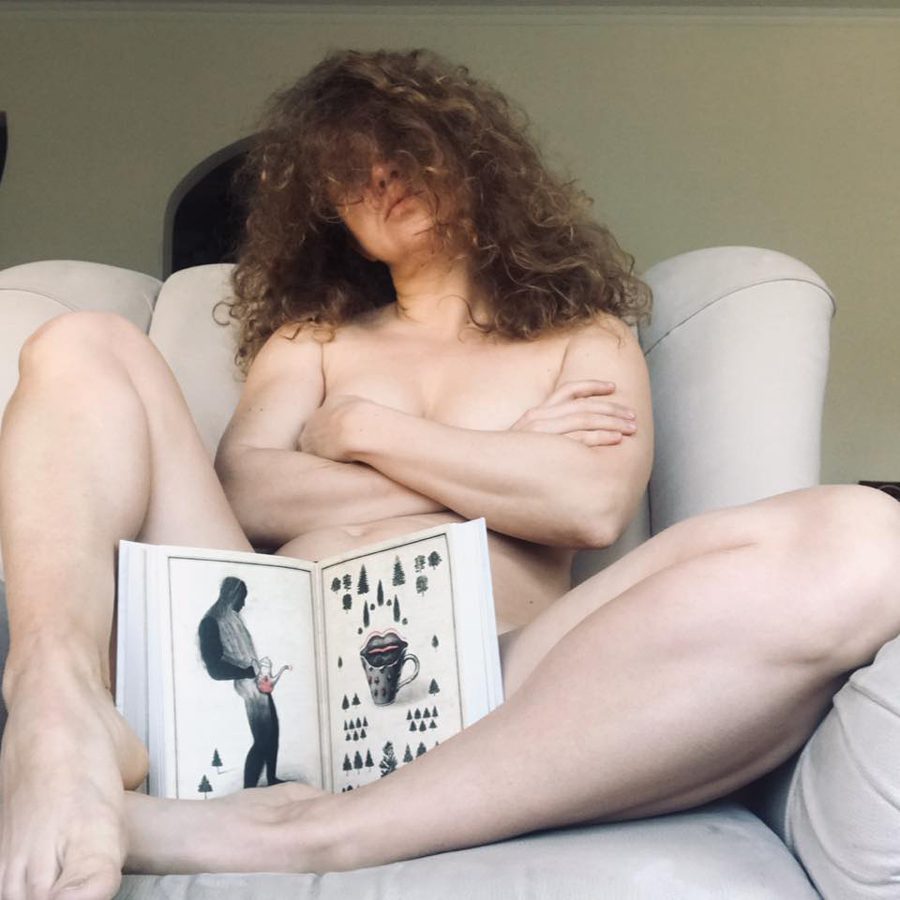

Naturalism occupies an integral part of the novel, as it does in Haska’s work overall. “I love the body and all bodily processes. It’s not just about sexuality”, says the writer. “Death is a sad and painful thing for me, but not ugly. Nothing bodily in me is disgusting. It has been important for me since childhood to know where my liver and spleen are. Usually, when we think of our internal organs, we think of them as hyperbolized”.

This naturalism is often criticized. For example, Dmytro Krapyvenko, a journalist with Ukrainian Week, wrote that a woman’s body was “somewhat invigorating”. He ended his response with a rhetorical question: “Have male authors ever written about the pleasure of scratching their balls and the insidiousness of a hernia or prostatitis?”. Although he is wrong, perhaps not having read Henry Miller, William Burroughs, Taras Prokhasko and Oles Ulyanenko at the very least. There is no ‘correct’ percentage of corporality in the text, no marginal depth of openness in the descriptions; naturalism is one of the ways of translating the world into text, as with impressionism or the absurd.

“A person can read a sex scene and think it’s disgusting. But if they get a chance to talk about it, it will be easier for them, because they read it in a book. There are many books with detailed erotic scenes, and in fact, this detail is needed; not everything can be conveyed through metaphor”.

Haska Shyyan

For Your Money and Ours?!

At first, the novel was hardly noticed. At the time when Behind Their Backs was published, Irena Karpa’s book Good Tidings from the Aral Sea came out, selling more because of Karpa’s popular media image. But shortly after its publication, Haska Shyyan’s novel received the European Union Literary Prize. It was the first time a Ukrainian author had received the prestigious award. On a wave of enthusiasm, everyone rushed to read the novel. Many did not like it.

The main character is apolitical. She does not broadcast cheers of patriotic sentiments because she thinks first of herself and not of the country. Moreover, she is skeptical of religion, masculinity, heroism, and traditional family values — basically everything that Ukrainians have been taught to cherish and respect since childhood. Through the prism of Martha’s disbelief, the reader witnesses the residents of today’s Lviv, military volunteers, and users of social networks. They were indignant in different ways; some recognized themselves in the novel and turned to personal insults of the author. Others accused her of slander, but for the most part, they were shocked by the treacherous position of the book, which hasn’t stopped collecting awards.

“We have a wonderful text-illustration about those who are ‘tired of war’, without ever feeling it and especially experiencing it”, wrote Maryna Ryabchenko, a candidate of philological sciences and book reviewer. “In my opinion, this text should offend the women who are waiting for their loved ones to return from the war. The real women who were reduced to the image of a drama-queen-who-does-not-understand-and-who-just-throws-her-man-out-of-her-life”.

Haska Shyyan explains that literary fiction still remains the invention of the author, despite the realism of the image. “It would be hypocritical to say that the main character is completely alien to me and I specifically described her as a greedy, rich, lustful bitch who thinks only of herself. Although I can’t say that Marta is my alter ego or a person who could be close to me. In some ways she is close to me, in some ways she is annoying. But I definitely felt her experience in my own skin”.

Even before the backlash, Haska Shyyan gave an interview, where she expressed that she was ready to defend the need for this book if there was anything against it. In response to speaking about the need for it, since the claims eventually did arise, Haska says, “The task of any work of art is to provoke questions, reflection, and doubt. I am glad that we have passed the phase of Soviet socialist realism, when what was written defined ‘what is good, what is bad’. There is one clear fact in the current political situation, and that is Russian aggression against Ukraine. Everything that happens to human destinies, experiences, and emotions because of that aggression is not black and white, and it is harmful to reduce everything to patriotic narratives”.

In October, the novel Behind Their Backs was selected in Book Pitch during the 11th Odessa International Film Festival. A new wave of backlash against the book began, with some people saying that the “unpatriotic novel” was also being screened for budget money, although this is not the case; the festival only recommends the book for filming.

Behind Their Backs is not the only novel to be nominated for this year’s Book Pitch. It shared the nomination with Daughter, written by the volunteer Tamara Horikha-Zernya. Since both touch on the subject of war (one is deeper and more patriotic, the other is more skeptical and indirect), they are often compared. Some readers claim that in an information war, books with ambiguous positions should be ignored and generally considered ‘dangerous to broadcast to the West’. While readers might share their frustrations in reviews, in the comment section under each post there are also threats against the author, such as “you should be beaten up for what you’ve done”.

Patriotism as a party request

Haska Shyyan explains this indignation with literary fiction as the lingering consequences of the Soviet period: “If in the last century you bought a novel in a bookstore, it was approved and verified. That’s how censorship worked, so people ‘trusted’ books. The text was meant to broadcast the party’s position. This is where this ‘the truth is in literature’ comes from”.

Haska mentions the case of French journalist Pierre Sautreuil. He wrote The Lost Wars of Yuri Bilyaev, a book about a Russian separatist who managed to become a cop, a bandit, and eventually a mercenary in Donbas. The author tried to understand the motivation of a person who goes to kill for other people’s territories. The presentation of the book was announced at the Lviv Book Forum. The organizers were accused of giving a voice to the enemy.

This reaction is common in Ukrainian society, where the war has been going on for seven years. However, Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, a novel about the senselessness of the American army, especially its leadership, was published in 1961— in the aftermath of World War II, during the long Vietnam War, and with the Cold War on the doorstep. Therefore, the idea that in the times of information warfare it is dangerous to talk about societal problems remains somewhat questionable.

Haska says that for her one of the most depressing narratives of the Ukrainian patriotic discourse is the idea of self-sacrifice: “If you live well, you’re not doing something patriotic enough. You stole, sided with the enemies or betrayed the country. To me, a patriot can also be a dude who opened a Ukrainian IT company and hired 100 people”.

When asked if she considers herself a patriot, Haska says that patriotism is a word that many are juggling with. “I am not one of those people who have unconditional love for the place where they were born. However, it is difficult for me to imagine that I would write in any language other than Ukrainian. And I do not think that language can be monopolized only by people of a certain political position. If I had to choose a quote broadcasting my opinion from my book, it would be that patriotism is formed by a cozy childhood”.

Translated by Kate Tsurkan