“On the Ninth Day, I Dug up the Body. I Took a Risk”. How a Pensioner from Yampil Tried to Bury His Wife with Dignity despite the Shelling

On September 30, the Armed Forces of Ukraine liberated the village of Yampil in the Donetsk region. When Zaborona’s team arrived in Donbas, the military warned us about possible artillery battles near Yampil, despite that there were still people in the village. On October 15, we met an evacuated resident of the village in Lyman — according to his testimony, there was not a single building left in Yampil that was not damaged in one way or another. Zaborona tells the story of the destruction of his life, family, and home.

Volodymyr Petrovych (his last name is withheld for security reasons) is 82 years old. He was born in Karpivka near Kharkiv. The man received a teacher’s degree at Donetsk State University and moved with his wife Valentyna to Yampil, where he was offered the position of director of a village school. In parallel with the directorship, Volodymyr Petrovych taught history and social studies.

When asked about the beginning of the war, the pensioner pondered and clarified which war it was about. He survived the Second World War but admits that the Ukrainian-Russian war is much more terrible.

“I did not think that our fellow Slavs could spread this whole mess like that. My daughter offered to go to a safe place, but I thought that I have a farm here, my own house, which we bought with my wife for our own money. I did not want to leave it all,” the man recalls.

There have been no battles near Yampil since 2014. After the full-scale invasion, the war came to the village in early March. At first, residents heard explosions in neighboring settlements — Lyman and Kreminna. And in the middle of the month, the first Russian missiles fell on Yampil.

“On April 30, my house was smashed. My room was destroyed, doors, windows, and the kitchen was bombed. Life began to break down. My wife and I held on. We had a summer kitchen, where the roof collapsed a bit. We repaired it and lived there,” says Volodymyr Petrovych.

-

Yampil village, 26 October 2022. Photo: DIMITAR DILKOFF/AFP via Getty Images

On September 10, the man and his wife celebrated her 77th birthday. At that moment, he recalls, the war near the village entered an active phase — Yampil was heavily shelled, and there was not a single house left that was not damaged by rockets and shells. It was dangerous to be on the street — everyone stayed inside their houses.

Cellar, explosion, apple tree

10 days after the first shell hit Volodymyr Petrovych’s yard, the second one came from the direction of Zakitne village, where Russian troops were stationed. Mines filled with sharp bolts rained down on Yampil.

That day, the man went outside the house to work in the garden, and his wife stayed hiding in the cellar. “The cellar was good, made of gypsum block. The wife was sitting on the boards on the third step from the top. The explosion. A column of smoke and dust rose to the sky. I came running, shouting “Valya! Valya!” I looked — the cellar, three meters deep, was damaged as if someone was digging a trench. She, poor thing, her arms, head, and legs were torn off. Her clothes were torn, she was all naked and black. I could not look — imagine, we lived together for 58 years. We have three boys and a daughter”, the man recalls.

After the explosion, Volodymyr found several men who helped him bury his wife. The remains of her body were put in a cloth and buried in the garden under an apple tree.

-

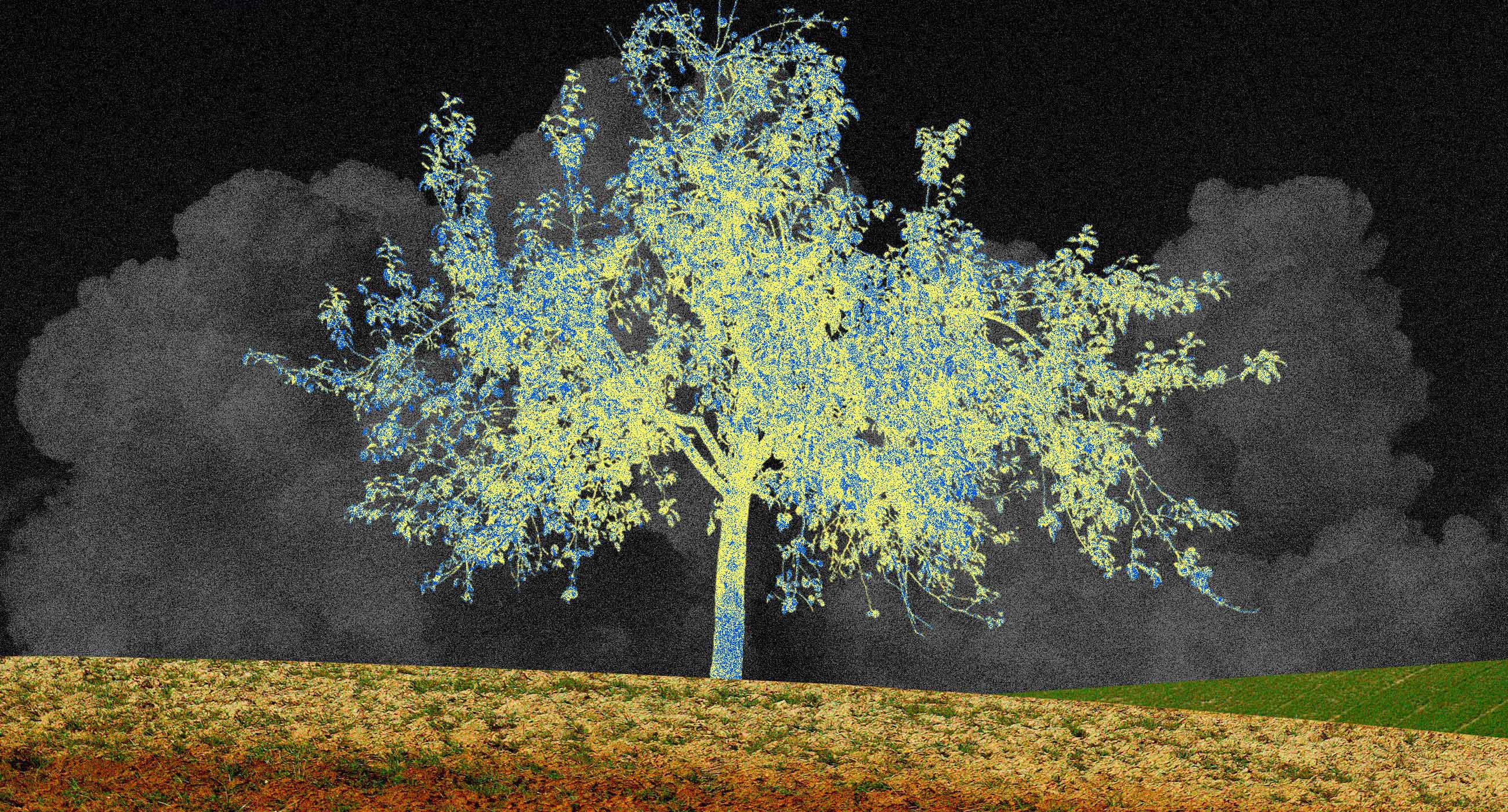

Collage: Maria Petrova / Zaborona

“She lay [in a freshly dug grave] for three days. But I was tormented by the fact that I did not bury her properly. Whomever I asked, I was told: you can’t, you need an examination. I have a car with a trailer, found a coffin, and covered it with fabric. On the ninth day, I dug up the body. I took a risk. I thought soldiers would interfere. No one touched me. I dug a hole in the cemetery near my son’s grave and buried my wife there”, Volodymyr Petrovych says.

“It seemed to me that this tragedy would not touch us. But it did. I never thought that she would be killed first. Poor thing was killed for nothing. She was not evil or aggressive, but she was a patriot. She was a teacher of Ukrainian language and literature”, the pensioner says.

Evacuation

The man did not want to leave Yampil. He took care of dogs and cats — they had to be left with a neighbor. The couple never went to resorts: they invested everything in the household.

“I had a good pension as a teacher, I received six thousand, my wife — four. We did not receive money for six months, we were living on stocks. We had a good garden, we had chickens, and once we had piglets. Everything was fine until they came. And now there is no strength to live there anymore. People fled from cities to villages, and I, you see, made it another way around”, Volodymyr Petrovych explains.

On October 15, in the morning, his former student arrived at the man’s house. It turned out that Volodymyr’s daughter had arranged for her father’s evacuation to Lyman. His entire life fit into a few bags.

-

Collage: Maria Petrova / Zaborona

“I had three closets of clothes. I took a phone, and a collection of watches — my sons brought them from ships’ voyages. You know, everything was important to me: shoes, pants, shirts. I have such a library left there. 720 books. I covered it with film, pressed down with chairs,” he says.

All the couple’s children now live abroad. The sons work as sailors on foreign ships, and the daughter lives in the Czech Republic. From Yampil Volodymyr Petrovych is going to Kramatorsk — his sister lives there. His daughter should come there to pick him up.

“I feel sorry for my wife. She was so radical, precise, correct. 58 years of life, four children — everything fell apart as if it had never been. No house, no wife, no children — nothing. That’s how it is,” he says.

-

Collage: Maria Petrova / Zaborona

This material is produced within the project «EU Emergency Support 4 Civil Society», implemented by ISAR Ednannia with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of “Zaborona Media” and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

The material was created within the framework of the “Life of War” project with the support of the Laboratory of Public Interest Journalism and the Institute for Human Science, Vienna.