Ukraine is attracting Islamic State militants seeking asylum after losing territories in Syria and Iraq. The country is a good place to hide and wait until you have the opportunity to return safely to your home in the European Union or elsewhere in the former Soviet Union. Polish journalist Pawel Pieniazek, who covered the war with the Islamic State in Syria and investigated the impact of terrorists in Afghanistan, and Ukrainian reporter Alyona Savchuk investigated how and why Ukraine has become a haven for some Islamic State militants.

In November 2019, the special services of three states — Ukraine, Georgia, and the United States — detained Caesar Tokhosashvili in Kyiv. His arrest came as a surprise for many reasons. Caesar is a fighter who is considered to be one of the key figures in the Islamic State (considered by most countries to be a terrorist organization), namely the “Deputy Minister of War of the Islamic State”, Abu Omar al-Shishani of Georgia.

Tokhosashvili, also known as Al-Bara al-Shishani, was thought to be dead. In August 2017, he and his family allegedly died in an airstrike in the Syrian province of Deir ez-Zor, which was then part of the diminishing Islamic State. But it was later discovered that his death had been faked in order to divert attention from his escape from Syria.

Tokhosashvili later settled in Bila Tserkva, a town 85 km south of Kyiv with a population of over 200,000 people. With the exception of a beautiful park, this is a typical post-Soviet city—that is to say, there is nothing extraordinary about it. The radicalization of Chechen militants – their transition to Islamic extremism – The proximity to the capital, the low cost of living, and some peace and quiet must have led to the fact that a relatively large number of migrants from around the world, including Muslims, have settled in Bila Tserkva. These factors are likely what attracted Tokhosashvili to the city, too.

“The SBU did not say much about Tokhosashvili, because it was a failure. He was in our territory for a long time without any supervision.”

Caesar probably worked as an unlicensed taxi driver or held a trading post in the market. He moved freely in the area, including in Kyiv. According to the Security Service of Ukraine, whose information is not always reliable, Tokhosashvili remained an active member of the Islamic State during that time. His tasks included recruiting new people, planning attacks, and coordinating the actions of Amniat, the IS security service.

Caesar lived in Ukraine for more than a year with his wife and three children. It is possible that he came to the country with real documents, and most likely, no one would have bothered him if the SBU had not received information about Tokhosashvili from the CIA and the Georgian Interior Ministry. Perhaps that is why the secret service’s great success was not widely publicized in the media, and information about the Georgian, which was published by the SBU, was scanty.

“The SBU did not say much about Tokhosashvili, because it was a failure. He was in our territory for a long time without any supervision. If we had known about him and kept watch, then it would have been a success,” explains SBU Major General Viktor Yagun, former Deputy Chairman of the SBU in 2014-2015.

The detention of such an important member of the Islamic State has led to a search for answers—how did it happen that Islamic State militants chose Ukraine as one of their “recreational bases”?

From the Georgian army to Syria

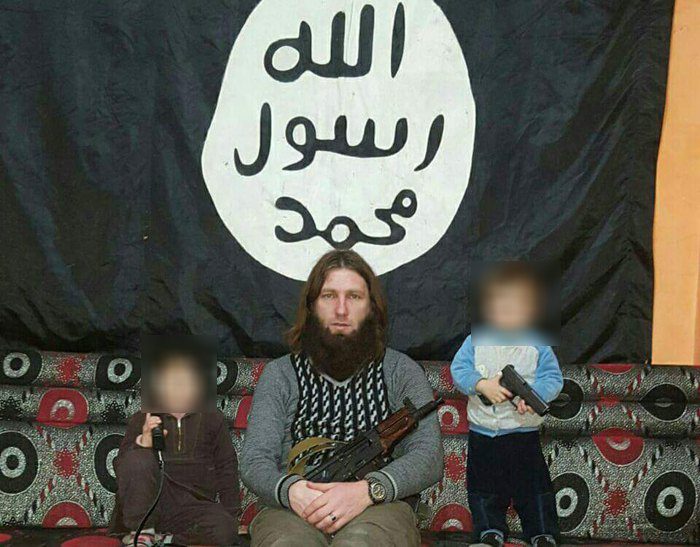

In the extradition photos from Ukraine to Georgia in May 2020, Tokhosashvili has short hair, a shaved mustache, and a short, neatly-trimmed beard. He is wearing a sports suit, sneakers, and a faux leather jacket. He looks older than his 34 years, and certainly much older than in his photos from Syria, published by researcher Joanna Paraschuk in the blog “From Chechnya to Syria”. In one of them, he has a serious face, a long thick beard, and shoulder-length hair against the background of the Islamic State flag. The rifle rests on his feet. Next to him are two of his young sons holding pistols.

Photo: chechensinsyria.com

Tokhosashvili was born in the Pankisi Valley in Georgia’s mountainous northern region, where mostly Kistin Muslims (Georgian Chechens) live. That’s why the Georgian’s previously mentioned pseudonyms include “al-Shishani”; in Arabic, it means “Chechen”.

The Pankisi Valley was an area of vital importance for militants who took part in the First and Second Chechen Wars at the turn of the 21st century. Supporters of the North Caucasus republics’ independence from Chechnya and Dagestan went there to hide from the Russian secret services. When the Second Chechen War began, Tokhosashvili was 13 years old. It is likely that he was somehow involved in it. It was the radicalization of Chechen militants—their transition to Islamic extremism— that changed Pankisi’s life. Especially the young bones, many of which were admired by the militants.

According to various estimates, the Pankisi Valley is home to around 10,000 people, of whom around 50 to 200 have left for Syria, where a civil war has been raging since 2011, killing hundreds of thousands. The Islamic State in Syria has attracted Muslims from all over the world, including thousands of residents from across the former Soviet Union. It is estimated that 40,000 people came to Syria and Iraq to support the organization. Although many were killed or arrested, large numbers returned home or hid in other countries.

The most famous Pankisi resident who went to Syria was Abu Omar al-Shishani, Tohosashvili’s peer and childhood friend. His real name is Tarkhan Batirashvili. He came from a mixed Christian-Muslim family and converted to Islam later in life. Batirashvili was also, to some extent, associated with the Second Chechen War. After graduating from school, he joined the Georgian army and took part in the Russo-Georgian war in 2008.

Two years later, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and Batirashvili had to leave the service. He later tried to re-enlist but was turned down. The local police wouldn’t hire him either. After that, police officers found an unregistered weapon in Batirashvili’s possession. Sources close to the previous leadership of the interior ministry informed Zaborona that he had been detained because of a conflict with the security services. Batirashvili was eventually imprisoned and served 16 months. At this time, his mother died of cancer. It was in prison that he swore to Allah that he would go to jihad. He reached Syria in 2012.

Companion in arms

Tokhosashvili arrived in Syria either the same year as Batirashvili or the following one. He and Batirashvili served in various jihadist units, which were much more moderate than the Islamic State’s then predecessor, the Islamic State of Iraq. During that time, a Ukrainian man also fought in Syria. Let’s call him Musa.

The man enters a small, relatively empty cafe near the train station in Kyiv. He sits away from other people so that nobody can overhear the conversation. Musa does not keep his life story a secret, but he does not want to attract too much attention. He is a little over fifty—although he says it feels like he has lived several lifetimes in the last five years. His appearance does not significantly differ from anyone else’s. He is of medium height, with a typical physique, and wears inconspicuous-looking clothes. The only noticeable thing, perhaps, is a grey beard that is longer than average. The special services are not interested in Musa, so he moves freely around the city.

His faith was also affected by the Chechen war. When militants were still being treated in the early aughts in one of Ukraine’s cities, Musa met them and, as he puts it, “returned to Islam.” He became interested, read, listened to sermons and watched videos sent to him by his new friends.

“My mother was most frightened then. But I explained that our religion teaches us not to kill or attack, only to defend ourselves. Defend yourself, family, property, religion,” says Musa.

One day he went to Belgium. There, in one of the mosques, he saw a man praying separately from the rest. Musa asked the locals why he was sitting alone. They told Musa that he considered everyone else to be an apostate.

“Later, such people formed the Islamic State troops, and the first thing they did was kill their fellow Muslims,” says Musa. “For them, we are apostates, and this is even worse than Shiites.”

Musa believes that he did not follow in their footsteps because he had good teachers and militants who explained that war was a tool, not a goal. The goal is justice and security. He is convinced that a state based on Islam should not be formed by violence, but when the Muslim community matures.

“Today we are not spiritually ready for this, we lack knowledge,” Musa admits.

He blames communism for everything, which for years did not allow Muslims, like Christians, to profess their faith.

“When communism collapsed, freedom appeared, religion became permissible, but the amount of information available was so great that it burned the processors in people’s heads,” he said.

A mutual friend

Musa fought with Batirashvili and his entourage in a jihadist group. He does not say which one, but most likely the Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar (Army of Migrants and Companions), created in 2012. Most of them were people from the North Caucasus. It was recognized as a terrorist organization, particularly in Canada and the United States.

Musa claims that he knew Batirashvili for a long time. However, he notes that it was difficult to talk to him because the Georgian knew very little Russian. Musa was in Syria just as the militants were fiercely debating whether to accept the invitation to join the newly-formed Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria. He decided to leave the country because, as it is said, the militants brought with them all the same problems from home that became even more noticeable during the war, and therefore, even more burdensome. Musa went to Turkey. While he was there, a comrade-in-arms called him and said that one night part of the group had followed Batirashvili and joined the Islamic State.

“They just ran away in the middle of the night, took our things, cars, and weapons, left their positions. They did the wrong thing,” says Musa. “And then they started shooting at their people”.

Among those who followed Batirashvili was a close friend of his, another Ukrainian from Kryvyi Rih.

As for Caesar Tokhosashvili, Musa never heard of him. He learned about his existence only after the Georgian’s arrest.

Photo: SSU Press Service

Ukrainian transit

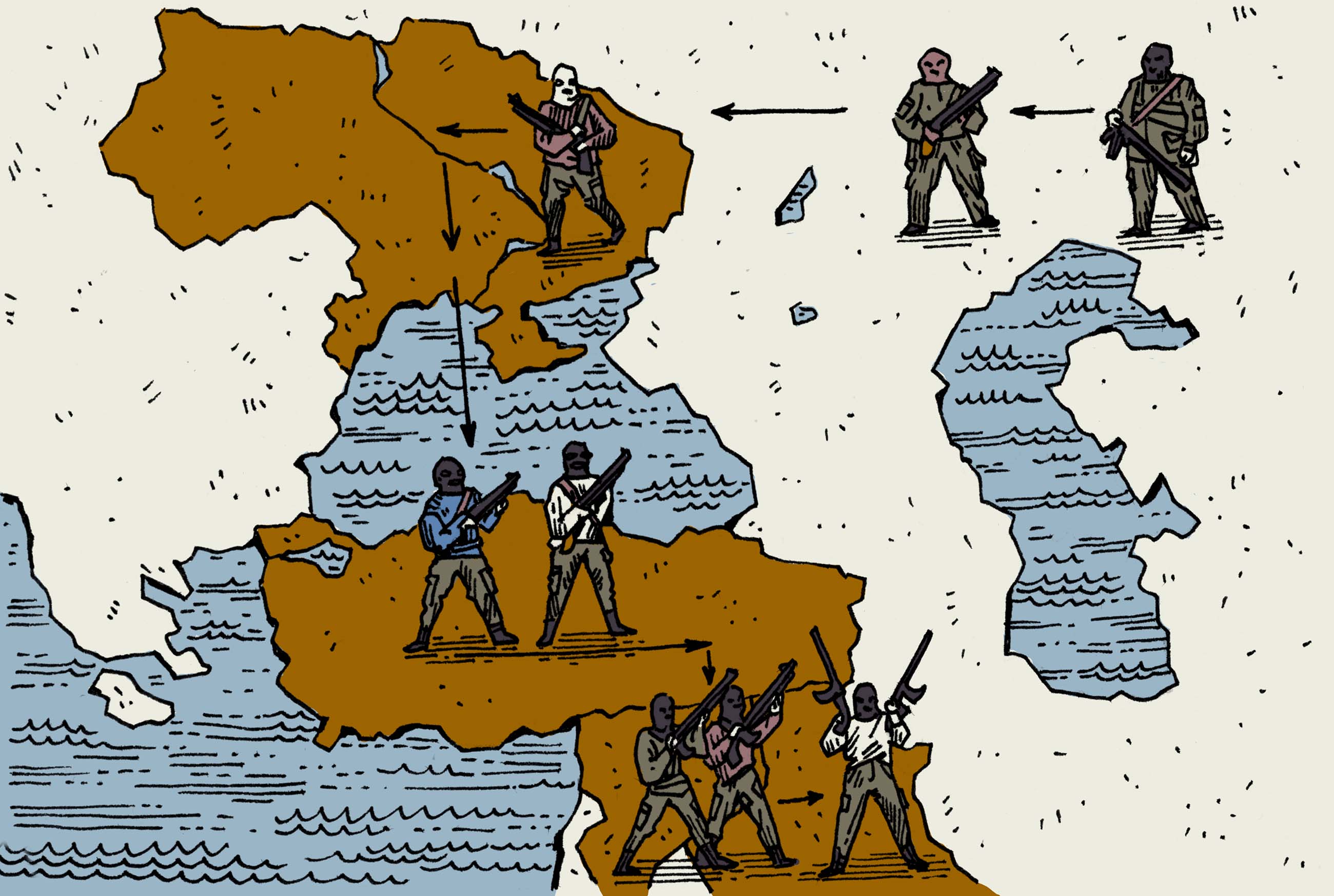

Musa left Turkey and quietly returned to Ukraine. He is not the only one. For years, Ukraine has been an important transit point on the way to and from Syria. The Security Service managed to disrupt several such operations. In July this year, two Azerbaijani citizens were sentenced to 10 years and 3 months in prison in Kharkiv for transporting Islamic State militants from the North and South Caucasus and Central Asian countries via Ukraine to Turkey, and from there to Syria and Iraq. The intensification of jihadists in Syria coincided with the Maidan Revolution, the annexation of Crimea, and the war in Donbas, so Ukraine paid little attention to the militants who were passing through its territory.

It was the same on the way back. Routes leading from Syria to the militants’ countries of origin were gradually blocked. However, Ukraine remains open to them today. There are various possibilities to get here: to fly by plane and pass passport control with real or forged documents or cross the Black Sea illegally by ferry. If a militant is not included in the Interpol database, he can easily enter Ukraine.

It is difficult to talk about this phenomenon’s scale—there is no independent data, only estimations. In 2016, the SBU said it had identified more than 100 people and detained 46 linked to “international terrorist and religious extremist organizations”, as well as 11 “crossing points” of Islamic State militants in Kyiv and Kharkiv. In addition, the SBU blocked two branches of the organization in Dnipro and Kharkiv, which provided material and logistical support to members of the group in Ukraine and helped them travel abroad. The agency also claimed that 443 people associated with the Islamic State were not allowed into Ukraine.

Since then, the SBU has regularly reported the arrests of people involved with ISIS, but this information often turns out to be untrue following verification.

As of 2017, according to Ukrainian media, at least 17 people accused of links to the Islamic State had been detained, including those who allegedly took part in the fighting and were responsible for leading the group. In addition, there are reports that people associated with the jihadist organization are not allowed to enter Ukraine from time to time.

At the request of Gazeta Wyborcza for this article, the SBU said that from 2014 to 2020, they were investigating 9 people involved in the Islamic State’s activities, and three more criminal proceedings are currently underway.

Turning a blind eye to threats

The above information refers only to those who were caught. But how many are still at large in Ukraine? According to various sources familiar with the intelligence community and researchers, the number of former Islamic State militants ranges from 50 to several hundred.

Musa believes it’s a lesser value. He says he knows a dozen men and women together who have visited the territory of the “Islamic State” and later returned to Ukraine.

“They returned and kept silent about their experience. Not out of fear—they just don’t want to relive what they went through.”

Photo: Vyacheslav Ratynsky / UNIAN

“One cooks kebabs, the other got married and had children,” he says. “They returned and kept silent about their experience. Not out of fear—they just don’t want to relive what they went through.”

He cannot say with certainty that these people abandoned their radical ideas because they were accustomed to hiding their true beliefs. But he emphasizes that many of those who once joined the Islamic State, including his comrades-in-arms, were ultimately disappointed by it.

Former Deputy Chairman of the Security Service of Ukraine Viktor Yagun agrees with this thesis.

“Many people have passed through the Islamic State. Not all of them wanted to fight or become martyrs, he says. “When they got there and saw the situation with their own eyes, their views changed dramatically.”

However, according to Yagun, there are hundreds of people associated with the organization in Ukraine. Despite recent detentions, jihadists are not the country’s top security priority, which is the war with Russia. It is the main threat to Kyiv.

“Islamic terrorism is not typical for our country. That is why the Ukrainian special services do not focus on it, “Yagun explains. “They act only on the basis of the fact: if another state asks to extradite a person or when information [about the militant] falls into their hands.”

Yagun believes that Ukraine is a recreation center for Islamic State militants, to which they do not intend to cause harm. There are many reasons for this. Ukraine is one of the safest places left for them after Georgia imposed harsh penalties on “terrorist” articles in 2015 and stopped turning a blind eye to those crossing the border, and Turkey began deporting more and more foreigners with questionable reputations. In Ukraine, returning from Syria is not considered a crime, so it is unlikely that militants would be detained.

Besides, a large Muslim community lives in Ukraine. Although its actual size is unknown, there are between 300,000 and two million believers according to various estimates. The most common answer is one million. This is a heterogeneous community, but mostly Russian-speaking, which a huge plus for foreigners from the post-Soviet space, as the different Russian accents do not attract much attention here. At the same time, Ukrainians are relatively tolerant of Muslims. Life is cheap here, and you can see a doctor for much less money than in the European Union. And if the clinic is private, no one will ask where the injury came from, even if it is a gunshot wound.

The high level of corruption in the country also makes for a strong argument. A person who wants to disappear can get almost everything he needs here for the right amount of money.

How to become a citizen?

Legalization and a new identity are the most desirable goals for such people. Since the start of the war in Donbas and the annexation of Crimea, when local units of the State Migration Service fell into Russia’s hands and the groups it supports, and Russian documents were distributed en masse to residents of the peninsula, Ukrainian passports have flooded the market. Blank original records can be purchased and printed so that there are no questions during inspection. Moreover, many Crimean residents who received Russian domestic passports after the annexation sold their Ukrainian ones for pennies. The buyer could paste his photo onto the document and use it to obtain a new passport, claiming that he had “lost” his internal passport and was applying for a new one, which was already fully valid.

The introduction of biometric passports and plastic ID cards has slowed the circulation of old documents but has not stopped it. The information published by the secret services shows that the problem is still relevant. Since 2019, law enforcement officers have identified at least three groups involved in the illegal issuance or forgery of documents. On August 28, 2020, the SBU stated that it had exposed a large channel through which foreigners were issued “high-quality” forged documents necessary for legal residence in Ukraine and travel abroad. The criminal group operated in at least five oblasts. Numerous documents were found in the apartments where the search was conducted, including forged European Union passports.

Photo: Mikhail Markiv / POOL / UNIAN

A Ukrainian lawyer (at his request, we do not give his name) who deals with migrants says that the problem is that the systemic and migration services themselves are involved in illegal activities. Even a real Ukrainian passport can be bought for money. Depending on the case’s complexity and the number of intermediaries involved, the amount ranges from $2,500 to $7,000, the lawyer said. Corruption also makes it easy to take advantage of options such as a sham wedding. They give the right to permanent residence, and eventually, citizenship.

A Ukrainian woman, who wishes to remain anonymous, says she has long been fighting for her husband’s citizenship, who hails from the Middle East. They set a goal to pass the procedure legally, so they had to hire a lawyer. Others in this situation choose a much more expensive but faster way, she said. According to the law, to immediately obtain a permanent residence permit, you must marry a foreigner who already has such a document; if one of the spouses is Ukrainian, they have to wait two years. The legal process requires many documents and some luck to get into the annual quota, but people can do anything without problems for the right amount of money.

“As a result, married men with many children come to Ukraine, get married for a while, and then divorce. After that, they get visas for their real family, bring them here and get all the documents,” she explains.

Home through Poland

Three people connected with the Polish and Ukrainian border services confirm that if the documents are in order, even if they are made improperly, a member of a terrorist organization would not be caught. He could easily get on a plane and go to any country that does not require a visa, including the European Union.

Those who cannot afford to spend thousands of dollars are left with the option of cheaper illegal border crossings. An employee of the Polish Border Guard Service, who agreed to speak anonymously, said that organized groups of smugglers charge between $1,500 and $3,000 for smuggling, a part of that amount going to bribes.

“We are catching ourselves,” because the border guards themselves are involved in smuggling.

“If a border guard takes a bribe, he will go to the right, and people—to the left,” he admits. For his part, former Ukrainian border guard Viktor Lebedenko recalls that the service said, “We are catching ourselves,” because, as he claims, the border guards themselves are involved in smuggling.

An obvious destination for those who want to leave Ukraine is Poland, where after 2014 it was impossible to control all the people who came to the country, which numbered in the hundreds of thousands. Did the jihadists use Poland to hide or as a transit stop? There is no such information because Poland, like Ukraine, does not consider this threat a priority.

“If you came to Poland as a Ukrainian according to Ukrainian documents, it is impossible to check you due to the large number of people,” admits Daniel Botskowski, a professor at the University of Bialystok, who studies national security and religious fundamentalism. “Here you can relax and wait for further instructions. At the same time, there are some of the militants who despaired of the Islamic State and sought a place where they could live peacefully and not be afraid of persecution for their crimes.”

The professor admits that Poland has probably not seriously considered the multitude of ways in which jihadists could enter the country, and now there is potential for the situation to get worse.

“If the threat is not monitored, it can get out of control. We are making the same key mistake that is inherent in intelligence services around the world because we believe that solving this problem is not as important as investing efforts and resources in it,” Botskovsky said.

Therefore, it is only to be expected that more than one former jihadist will be found in such “recreation centers” as Ukraine and possibly also in Poland.

The text was edited by Katerina Sergatskova.