The Zaborona author Oksana Semenyk lived in Bucha near Kyiv with her partner, photographer Oleksandr Polenko, when Russia started its all-out incursion into Ukraine. Because of the ceaseless shelling, they had no possibility to travel to a safer place. They spent fifteen days in a bomb shelter near a Russian army post. During their final days in the shelter, there was no food, heat, or telephone connection and no one was able to help them evacuate. ZABORONA publishes the journalist´s monologue.

I moved to Bucha in September and Sashko joined me in November. We lived in our apartment, arranging things, buying furniture, combining our books and other possessions. And then came the war. Our building was bombed a number of times. Our balcony was destroyed and windows were blasted out. But we didn’t go out to inspect the damage because anything could happen from minute to minute.

The third balcony from the top was Oksana’s. Photo: Oksana Semenyk

On the first day (Feb. 24), we were still at home and spent the night in our apartment. But we were very close to Hostomel’ [where there was a very fierce battle going on for the airport] and we could hear the loud planes very clearly. We couldn’t sleep normally. Some residents went down to the cellar but the cellars in our town were not fit as shelters – no light, no anything. We decided it was too dangerous a place to stay, that if the building were to collapse, that would be the end. And so we moved to a shelter at a kindergarten. That building had only two stories and a large shelter furnished with chairs and places to sleep. The kindergarten was in the building next to ours which, in times of peace, seemed very close by, but when you are running and dodging bullets, it is very far.

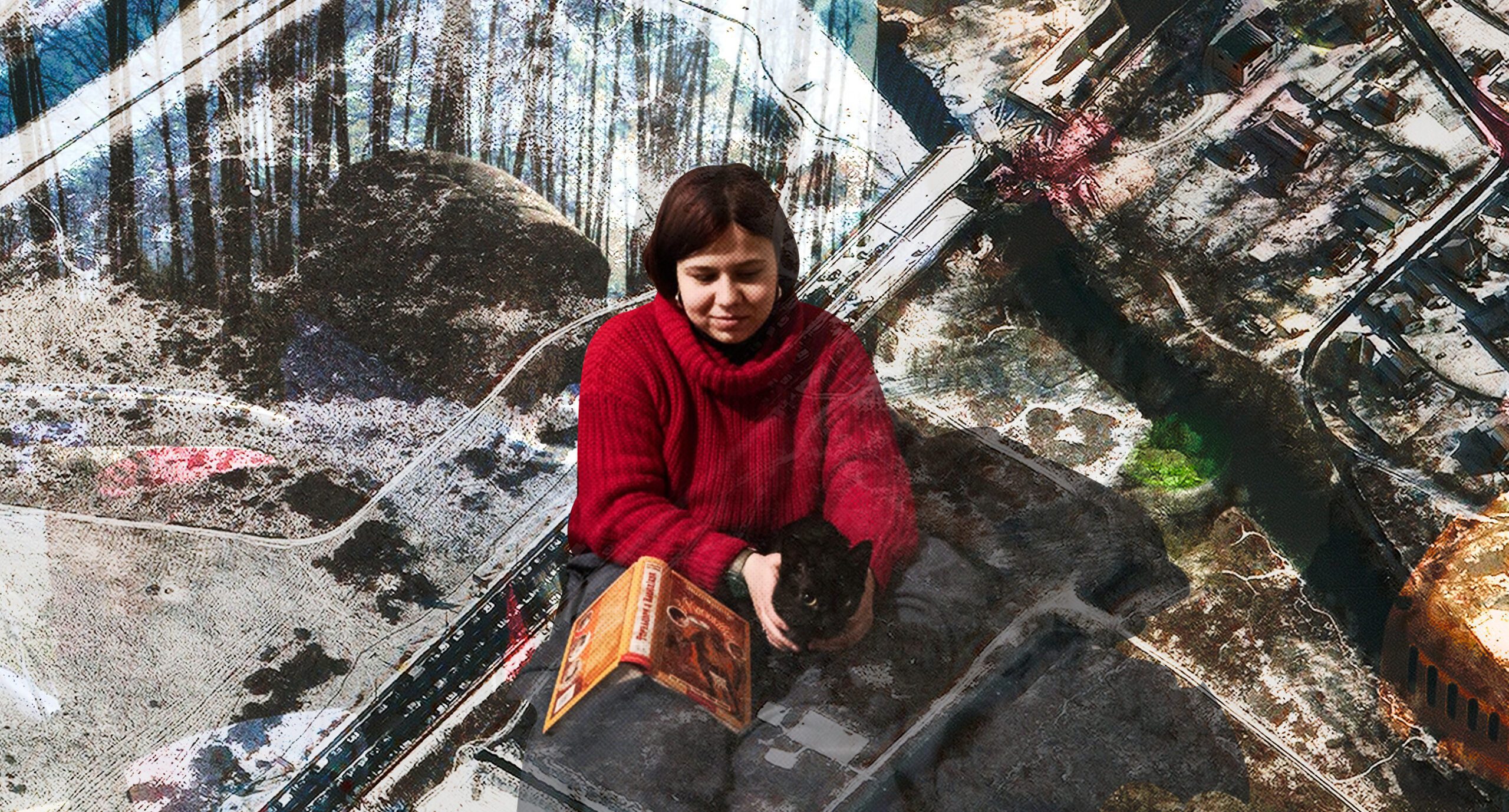

Photo courtesy of Oksana Semenik

We left our apartment for good on the second day. I had prepared an emergency kit on the first day with all medicines that we needed, warm clothing, our documents, toiletry necessities, a book by [the writer Serhiy] Zhadan “The Templars”, and what food was left for us and our cat. We arranged our cat’s things: bowls, its sandbox, everything that was needed. We decided to sleep at the shelter and return to the apartment to bathe and eat. But then the direct bombardment of our area began.

Why didn’t we leave right away? We were new in Bucha and didn’t have any friends there. We didn’t have either a car or a [drivers’] license. For us to get out of Bucha, someone would have to drive into the town and no one was prepared to do that. For the most part, we were told, get out of the city and we will pick you up there.

There was a day when they said Bucha was regained and they hoisted a Ukrainian flag. That was about March 4th. But, in fact, that was untrue and Russian hardware was already entering the city. That was when the most brutal phase began. Fighting was taking place in our own neighborhood; you could hear machine-gun fire and a column of tanks was rumbling down our streets. Afterward [the occupiers] started going through people’s apartments and destroyed the water tower. Water and light disappeared. The Russians started going through houses asking who was where and breaking into *Fora” and another store. They walked through our neighborhood as if they were at home. We stayed in the shelter for three days without light and didn’t open the door for anyone. At that time there was still a telephone connection and the people who had stayed in their homes and didn’t go into shelters called the people in the shelter with us and told them what was happening. They sent us photos of the occupiers sitting on a bench enjoying their beers.

They Boiled Some Oatmeal While There Was Light

There were about thirty people with us in the cellar, many of whom were children. We slept under a fleece blanket in our clothes on an old mattress that we had dragged from home. That was all we had. We used our rucksacks until someone even gave us a pillow.

Photo courtesy of Oksana Semenik

To eat we had Bounty and Snickers candy bars and some baked goods. When there was electricity we cooked some oatmeal. When the light came back on we ate the bread, sandwiches, and sweets that we had brought with us. There wasn’t much food but if we ate just a little we could hold out for a week. We ate twice a day, but not always because we were too nervous and were always nauseated.

We had enough water. On the first day, we filled our bottles from the faucet. It wasn’t drinkable water but that was not important. But when the occupation began [the Russian soldiers] left the private homes and set up a base somewhere so some people started to take water from wells.

We kept track of news as long as there was the Internet – that was all we could do. When we started losing connection but there was still light, I read “The Toreadors of Vasiukivka” [by Vsevolod Nestayko] which really kept my spirits up because it was very funny. Sashko tried to photograph life in the cellar but what can you do when the light goes out? Nothing. You lie there, you sleep. You play with the children and stroke your cat. You think about how soon you can leave the shelter. We listened to the radio “NV”. It turned out that we could listen on the phone although there was no connection and this really saved us.

Plans for the Future

On the third day, Sashko and I decided to get married. On that day we had the chance to leave but we couldn’t. We sat in the cellar not knowing what would happen next. They were shooting right next to us. I asked Sashko – what should we do? He said – Well, we’ll start a family. I said – Now be serious. I was wearing a ring that my godmother had given me on my eighteenth birthday. I said – Take this ring and put it on my ring finger. And so we started to plan our wedding. We decided we wanted to marry on Independence Day at the central registry office and would invite all the people who were worried about us and had asked how we were doing. We just weren’t sure about the witnesses yet.

Фото надане Оксаною Семенік

During the past few days, we had no connection to the outside world. Sometimes the Internet returned and there was news but we couldn’t open the files. Someone wrote – Walk to Irpen’; but there was a Russian post on a parallel street. What could you do? Ask them politely to let you pass through? In the cellar, there was an area representative who was in contact with the local government. They tried to calm us with expressions such as – We are thinking of you – and so on. But we were not in the center where people were being evacuated. We were too far away.

There was very little news available. You didn’t know whether your city was being occupied or whether that was only in your area. Some news got through to us but we didn’t know how to react. We understood that the Ukrainian Armed Forces couldn’t announce where they were in control but that made us nervous because we couldn’t figure out which way to flee.

A Sudden Decision

At one point we got up in the morning, finished our last cigarette, and saw that people were getting ready to walk – and we went with them. This was decided suddenly, in a flash. This was how our conversation went: “Where are we going? “ “What the fuck” So we go.

We tied white armbands onto our sleeves to show that we are civilians and went. The first thing we saw was a building where several apartments had been burned out. We set out in the direction of Irpen’ but a Russian checkpoint turned us back and told us to go in the opposite direction. We went in the direction of Zhytomyr through Stoyanka, Dmytrivka, Kapitanivka and reached Horenychi on foot. We didn’t know where we were going – we just walked. We didn’t know which areas were occupied and which were not. Russians at their posts asked us where we were heading. We answered – Just away from Bucha.

Evacuation from Irpen, March 8, 2022. Photo: Diego Herrera Carcedo / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

A Twenty-Two-Kilometer Walk

We were a column of about two hundred people. Little by little, cars that drove by us picked up women, children, and the elderly. But not all of them stopped. Many cars drove by half empty or filled with possessions and didn’t take anyone. That angered us a lot. Then we walked on the road to Zhytomyr and no one stopped. There you are, barely dragging your feet behind you, carrying your rucksack and holding your cat. We walked for twenty-two kilometers. Ania [Tsyhima, a journalist] picked us up with her car in Horenychi.

While we were walking we weren’t afraid of anything. We didn’t give a shit about the machine guns or the Russians or what they would ask us or what they wanted – whether you’d get hit while walking or not. Explosions somewhere, something on fire. Maybe you’ll sleep in the forest or reach Kyiv on foot. Fuck it all. It was simply impossible to stay where we were. You either had to get out or not know if you ever would.

We’re in a safe place now. It’s hard to get used to being in a normal place and not in a cellar. We feel like we’ll wake up and all of it was a dream and we’ll be back in the cellar.

Photo courtesy of Oksana Semenik