Khadija and Her Boys.

What It’s Like Searching for Family Lost in the Islamic State

Author: Katerina Sergatskova

Visual concept: Katerina Sergatskova

Sculptor: Tasha Levitskaya

Shooting, processing: Snezhana Khromets

After the defeat of the Islamic State, thousands of people worldwide are trying to locate and bring home their relatives who left for Syria and Iraq a few years ago, joining the most brutal and large-scale terrorist organization in modern history. Kateryna Sergatskova, the editor-in-chief of Zaborona, tried to find Tetiana Kobeleva’s family, who went missing in 2017 in Iraq, and tells what obstacles relatives of the most hated people in the world have to overcome.

Tetiana Kobeleva takes off her glasses and then quickly puts them on again.

“I don’t understand what is written here. Is this what I told you?” she asks me, peering at the page with the statement. Then she grabs hold of a thick folder with papers and nervously pulls out of it requests to Interpol, SBU, the office of the Ombudsman, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and so on. “Is this really necessary? To show them that I have already addressed all of them, but they did not answer…”

October 2020. Tanya and I are sitting in a cafe near the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine. That is to say, I am sitting, and Tanya is continually jumping up from her seat and running off somewhere—this time, it’s for mineral water; earlier, it was for cookies; and after that, for something else. From time to time, she grabs her things: a suitcase on wheels and a bag of documents. Her hands are shaking, but who wouldn’t be nervous in her place? Tanya has been waiting for this moment for almost five years.

After a long silence, the Foreign Ministry started meeting with the women who are seeking the return of their daughters, nieces, and grandchildren from refugee camps and prisons in Syria and Iraq. What were their relatives doing in these countries? They were living under the rule of the so-called Islamic State, considered a terrorist organization by almost every country in the world. Most of their stories are similar. The husband was invited to participate in the “construction of the Caliphate,” and the family followed him. They lived in the Islamic State, there was a war, and things got worse. In early 2019, the head of the organization was crushed, husbands were killed, and thousands of women and children were sent to camps controlled by security officials from different countries and jurisdictions, and now they are begging their relatives to help them get out of there before it’s too late.

Nobody wants to help them. Members of the Islamic State and their families are, frankly speaking, the last people on earth that anyone would like to help. And why? Nobody knows what problems they face. After all, where is Ukraine, and where is the Middle East?

Tetiana Kobeleva also did not know anything about the Islamic State until her daughter and her little son ended up in Iraq.

1. It All Started Earlier…

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Getting to Tanya’s home is not easy: she lives in Saltovka, the largest residential district in Kharkiv and all of Eastern Europe. The Khrushchyovkas (a nickname for the old, Soviet-era residential buildings) have long been subject to demolition and the apartments in them are tiny, like matchboxes.

“I live here with my cat,” says Tanya. “Mostly, I just sleep. I rarely cook. Shuffling around, going to bed, going to work—that’s how my life goes by.”

Outside the window is a gray-blue day. It is said that gray is the color of Kharkiv. Every day Tanya waits for sunset and goes to work in the store. It’s cold in the apartment. The heating system works, but the walls are too thin to keep warm. Tanya has an old computer with a yellowed power supply unit in her tiny, dark bedroom. She walks around the house in warm fleece sportswear. Her gray hair is pulled back in a ponytail, and there are glasses on a chain around her neck.

A few years ago, Tanya lived with her daughter Natasha (whose name has been changed for safety reasons) in a completely different apartment. Life was hard. Tanya earned little money in the store; her daughter was studying at the Academy of Management and worked as a saleswoman. Natasha is my age: this year, she should have turned thirty-two. At the end of 2010, her son Petya (whose name has also been changed) was born, but she had to raise him without a father. Tanya and her daughter did it together. She says that he was her “our boy”, hers and her daughter’s.

Once, says Tanya, a customer, a young Jordanian, came to Natasha’s store. She called him “the student.” The Jordanian had come to Kharkiv to study, like many Arabs, to be a doctor. The “student” started a conversation with Natasha about trivial things. Then she met him again by chance. Then again, and again, and again. The “student” said that this series of meetings was not accidental, and they were destined to be together. He began to look after Natasha and soon moved in with her. They married.

All this developed secretly from Tanya for about six months, until events took a frightening turn. Tanya recalls that at the end of 2013, her daughter called and told her that she wanted to run away.

“He beat her and broke her down her spirit,” says Tanya. “He scared her with a taser. He threatened her, saying ‘We have finances, we have strength’. He said he would pour acid on her face if she tried to leave and didn’t let her work. She was afraid of him, but she only told her friends about it. She probably knew how I would react, that I would do anything to protect my children. So she stayed silent and endured all this.”

Once, says Tanya, he threw a laptop from the eighth floor, which she had presented to her daughter.

“Mom, be thankful that it wasn’t me,” Tanya recalls her daughter’s words.

This made Tanya angry. When she was still a child, her father would beat her. Tanya’s mother died when she was nine, and there was no one to protect her from the tyrant. Then there was her husband, who also tried to harm her, so she divorced him.

“I took my daughter to the edge of the city, rented a room, hid out there,” Tanya recalls. “I filed for divorce, went to the courts. During that time, I was also studying, working, and taking my daughter to school.”

But after…

November. In Kharkiv, there is a gray slime underfoot. Tanya runs between work, home, looking after her daughter, taking her grandchild to kindergarten. Hard, but still better than it was. Suddenly, says Tanya, the “student” catches Natasha after class and says: “That’s it, I won’t offend you anymore, I’m sorry, I was wrong.”

“She believed him” laments Tanya. “Our girls always believe such men. And then he moved into her apartment, surveilled her phone, prohibited her from communicating with friends, started taking her child to kindergarten. She insisted that she wanted to get married. She told me that she didn’t want to raise a child alone as I did. She thought that if she listened to him, everything would be fine.“

Natasha with the “student” and her son returned to her room in a communal apartment.

Summer 2014. There is a war in Ukraine. In Kharkiv, this is acutely felt, like nowhere else, for the wounded are brought continuously here from Donbas. Thousands of internally displaced persons and people in military uniforms appear in the city.

Natasha walks with her child in the yard and meets a girl in a hijab, Sabina (whose name has been changed). It turns out that she lives nearby. She was also with a child. They started talking. She said that she had been “in Islam” for seven years. They began to communicate, and Natasha became interested in the “rules of Islam.” Her husband allows her to communicate with this new acquaintance: on the contrary, he says that it is “possible” to speak with her. More than a year has passed like this. They begin to visit each other, spend time together. At some point, says Tanya, Sabina persuades Natasha to rent a separate apartment for herself and her husband, so that there are no extra ears. Sabina introduces her to two men from Azerbaijan and Russia who also live in the neighborhood. Tanya’s daughter does not tell her anything: she learns about all of this from another source or guesses herself.

Tanya is sure that at that time Sabina and those men were part of a group of Islamic State recruiters who were paid for the supply of manpower to Syria. It seems to her that Sabina had added “psychotropic substances” to her daughter’s food, but she has no evidence, only guesses. Her daughter could not, says Tanya, get so quickly hooked in by such people.

She shows me pictures: here’s her daughter performing at a concert in honor of her graduation from college, here she opens the Ice Arena. In the next photo, her daughter is already in a hijab.

“How could she, of her own free will, go to Syria? She’s a smart girl!” Tanya laments.

In the summer of 2015, Sabina invited Natasha to go to Turkey to unwind and get away from the war for a bit. Natasha agreed, and they helped her and her son make passports.

Soon she called her mother and said that she and her son were being taken to the airport in Boryspil. Tanya became wary. The daughter added: “There are many men around.” Those were her words— a lot of men. Her daughter’s tone seemed strange to her. After the call, communication with Natasha was cut off.

2. Everything happens for the first time.

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

A couple of weeks later, Natasha called Tanya from Sabina’s phone and said: “Mom, they are putting us on the bus.” She said that there would be a tour of Turkey. Tanya recalls that her grandson was crying and shouting that he wanted to go home in the background. In response to a question, Natasha suddenly said that she was sick and that someone had “given her a pill.” As Tanya later found out, her daughter was in the first weeks of pregnancy. After that conversation, Natasha disappeared from her radar for three long months.

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant was formed in 2013 from the Iraqi arm of the jihadist organization Al-Qaeda and its Syrian supporters. The terrorists sided with the opposition to the incumbent President of Syria, Bashar al-Assad, who has remained in power since the Arab Spring protests, which began in 2011. At the beginning of 2014, the group started to fight with the Al-Nusra Front and the Free Syrian Army, their former allies, and seize more territories. In the summer of 2014, under the leadership of the Georgian Chechen Tarkhan Batirashvili, known as Abu Umar al-Shishani, it invaded Iraq. It captured the country’s second most important city, Mosul. In the main Sunni mosque, al-Nuri, ISIS head Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi proclaimed the Caliphate. After that, thousands of people from all over the world poured into the territories seized by the organization to live in a world where everything worked according to the “rules of Islam”.

By the summer of 2015, ISIS already controlled 40% of Iraq’s territory and 70% of Syria. By that time, the whole world had already learned how thousands of Christians and Muslims who did not comply with the radical interpretation of Islam’s laws were being executed by the Islamic State.

Before her daughter’s disappearance, Tanya had never heard of the problems in the Middle East and was not aware of the Islamic State’s existence. Soon after her daughter flew “to Turkey”, Tanya ran to the police and reported her missing. The police registered a case of premeditated murder.

Then she ran to the Security Service and Kharkiv Interpol. But she was told that Natasha was an adult girl and she was free to choose where and with whom she went. The relatives of the Jordanian “student” turned to the Turkish police and were convinced there that the couple would not go further than Turkey, and that they were “being watched.” The SBU told Tanya about the Islamic State and the fact that for each person sent to ISIS, the recruiters, most likely, received several thousand dollars. Even for the baby in the womb – so she was told.

And then…

Tanya’s daughter got back in touch with her in the fall, once again from someone else’s phone. She did not say what happened. She spoke softly and smoothly. Tanya asked her a million questions, but her daughter for some reason did not answer the most important one, that is, where she was. Later, Tanya recalls, she was told that during the “tour of Turkey” Natasha and her son were first taken to Gaziantep, a large city in the south of the country, and from there across the border to Syria. But Syria is big. Where exactly they had settled, she did not know.

For some reason, Natasha always got in touch at night. Tanya thought: well since everyone is asleep, you can finally talk.

“I asked her: what is visible through the window? What country are you in? Are you alone?” Tanya recalls. “And she switched to Islam [quoted the Koran]. I heard a rustle nearby. I told her that I understood everything. There was always someone near her, in control. I told her: we will buy your freedom, no matter the cost, just tell me who to pay.” Once, Tanya recalls, when there was no one around, her daughter told her: “Mom, think about what you are saying: every message here is read, and every conversation is listened to. They cut off people’s heads here, you must understand where I ended up.”

Tanya shows me photographs of her daughter, taken at the end of 2016. A young woman with a friendly smile hugs a thin boy of about seven. She is wearing a black hijab with a bare wall in the background. No details by which one could guess their location. Tanya says that these photos were taken in the basement of the house where her daughter and grandchildren were accommodated when the shelling was going on. The youngest son was almost a year old. “But you can not show them to anyone. They could kill her for it!” she says.

Women living with Islamic State militant families were forbidden to tell their loved ones where they were. Conversations with the “house” were closely followed by the Hizba, the women’s Sharia police. Any attempts to transmit data on whereabouts and complain about living conditions were punishable by prison sentences at best, torture and death at worst. At that time there was already enough evidence of the brutality of the Islamic State militants to understand how serious everything was.

“Sometimes they were taken to the store,” Tanya recalls. “Then my daughter called me and said: if I ever lose touch with you, don’t dial any of these phone numbers. She knew that I would start asking a bunch of questions, and that would make her feel bad. One day they were at the store and I heard that her eldest son was crying. I asked what was the matter, and she said he did not want to be on the street, he wanted to go back to the room. I understood that there were people around with weapons, and he was afraid of them.”

Meanwhile…

Tanya was not the only one. By the summer of 2015, thousands of parents already knew where their children had gone. Botagoz Makhatova, a member of the Kazakh parents’ movement to find and return their children who lived under Islamic State rule, says that in 2013, five parents traveled to Syria to persuade their children to return, but were only able to take their grandchildren who had been born there … They were among the first to try to stop the outflow of citizens into a foreign country at war.

At that time, about two thousand young people left Russia for Syria, mainly from the North Caucasus and Tatarstan Republics. Approximately the same number of people went to fight for the Islamic State and other radical Islamic groups from Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Azerbaijan. In all these countries, closed associations of parents began to form, looking for their relatives in the territories occupied by ISIS. They exchanged experiences and information about where their children might be. The news did not talk about such things. On the contrary, the authorities in most post-Soviet countries issued special laws that prohibited talking openly about things related to the Islamic State. Parents risked ending up behind bars because of the actions of their children.

Tanya did not understand the world in which her daughter found herself. From new acquaintances in online parental support groups, she learned that Natasha was called Khadija, and the eldest son had been converted to Islam. The youngest, a newborn, was also given an Arabic name. Tanya also learned that her daughter and grandchildren were living in Mosul, the Islamic State’s Iraqi capital. It was from there that she contacted her for the last time in February 2017.

3. Witnesses

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

A wide variety of young people were traveling through Turkey to Syria at that time, and their parents, as one says, could not stop them.

Rushena Takhirzhanova is a young Crimean Tatar. She left Kyiv for Turkey and then for Syria when she just turned 18. She says that she followed a Chechen she had met online and could not even imagine what this acquaintance would turn out to be. I exchanged audio messages with her through Facebook Messenger. She is in a women’s prison in Baghdad: an Iraqi court sentenced her to 20 years in prison for participating in the Islamic State. Rushena lived in Mosul, but before the complete defeat of the group, she left for Tall Afar, and in August 2017, surrendered along with other women to the Kurdish Peshmerga army.

The Russian Air Force service spoke about Rushena’s difficult fate in 2018, but I am primarily interested in something else: if she had seen Khadija in Mosul. She confirms that she had seen and even made friends with her.

“The last time we saw her was in a hospital in Mosul,” Rushena says. “It was in February 2017. I came to visit her every day. She had two children, she was a very good girl, cheerful and sociable.”

Rushena talks about Khadija in the past tense: she thinks that she could hardly have survived the bombing.

“It’s unrealistic, the bombing was just too intense,” she says.

The Iraqi authorities, along with coalition forces, responded to ISIS attacks with artillery and aircraft. Hundreds of people died on both sides every day.

In February, the Iraqi army completely liberated the eastern regions of Mosul and launched an attack on the western part of the city. At that time, the military had already regained control over the Mosul airport and the south’s al-Ghazlani military base. At the same time, the center and north of the city remained under the militants’ control. Rushena says that in February, ISIS commanders transported them to a hospital in northern Mosul, thinking that it would be safe there and would not be targeted by an air attack. This was a mistake: as soon as the Iraqi special services learned that ISIS kept families of foreigners in the hospital, they immediately began bombing it.

“We were evacuated from there. They took me to Tall Afar, and after that, I did not see Khadija again. But she stayed in Mosul for sure,” Rushena says.

At that time, Khadija’s husband, the Jordanian “student”, had died. He committed a terrorist attack in Iraq in October 2015. Rushena says that after that Khadija was married to a man from Russia as his second wife. What region he was from and what his name was, she does not know.

After…

I am introduced to Fatima, a Chechen woman with a German passport. She does not give her last name so as not to harm her family. Fatima returned from Iraq and has been back in Germany for a couple of years already. It all started in much the same way as the others: her husband said that he would work in Syria for the benefit of the Islamic State, and she decided to go with him. She says that she had no idea how she would live with two small children without a husband. Furthermore, he told her that there it was “like Saudi Arabia or Kuwait, only poorer.” In July 2015, they ended up in Raqqa, and from there, they were transported to Mosul.

When the operation to free Iraq from ISIS began, Fatima and other families started to be transported from place to place. In April 2017, she was settled in an area referred to as Babatob, where she and other Russian-speaking women lived in Mosul under ISIS. This is Bab al-Tawb, a place near the bus station. “Bab” in Arabic means “gate”. The bus station borders on the old town and there is a large bazaar near it. The ISIS wives were taken there on weekends for shopping.

Mosul before destruction, 1932. Photo: American colony photographers / Wikimedia

Mosul before destruction, 1932. Photo: G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection / Wikimedia

“Khadija was preparing food for the children, but they did not have time to bring my things, so I asked her: can you give my children something [to eat], even a cup? She offered noodles,” recalls Fatima. “If you ask me, she’s a very good, respectable woman. I didn’t communicate closely with her, but we sat and talked when there were any questions. She did a lot of work with her eldest son. Even though there was no school, he knew mathematics. She focused all her attention on her children. When other women chatted, gossiped, she was busy with the children.”

Fatima says they were evacuated again a month later. At that time, Khadija’s second husband died, and she once again found herself a widow. Therefore, says Fatima, she was moved to a house for widows, and Fatima was again moved to a “family” house.

The ring around the “Islamic State” was narrowing every day. The Iraqi army fired mortars, and aircraft from the sky hit houses. The key battles were concentrated in the old city, and it became more and more difficult to move around it. Fatima recalls that evacuation from one block to another began to happen almost every day in the summer. Women and children were moved closer and closer to the river since it was more difficult for the army to get there.

“By June we were fully surrounded. The family and the widows were moved to the same house,” says Fatima. “They launched rockets at us; everyone sat in fear. When I entered the house and asked for a place for myself and the children, I was taken to the basement, and there I saw Khadija. She was with her children. They were not wounded.”

A month later, the ring finally closed and the Iraqi army announced victory over the Islamic State in Mosul. Fatima and her children came under an air raid in one of the quarters on the Tigris slope; she miraculously survived and surrendered to the soldiers. She still knows nothing about the fate of her children.

4. Territory

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

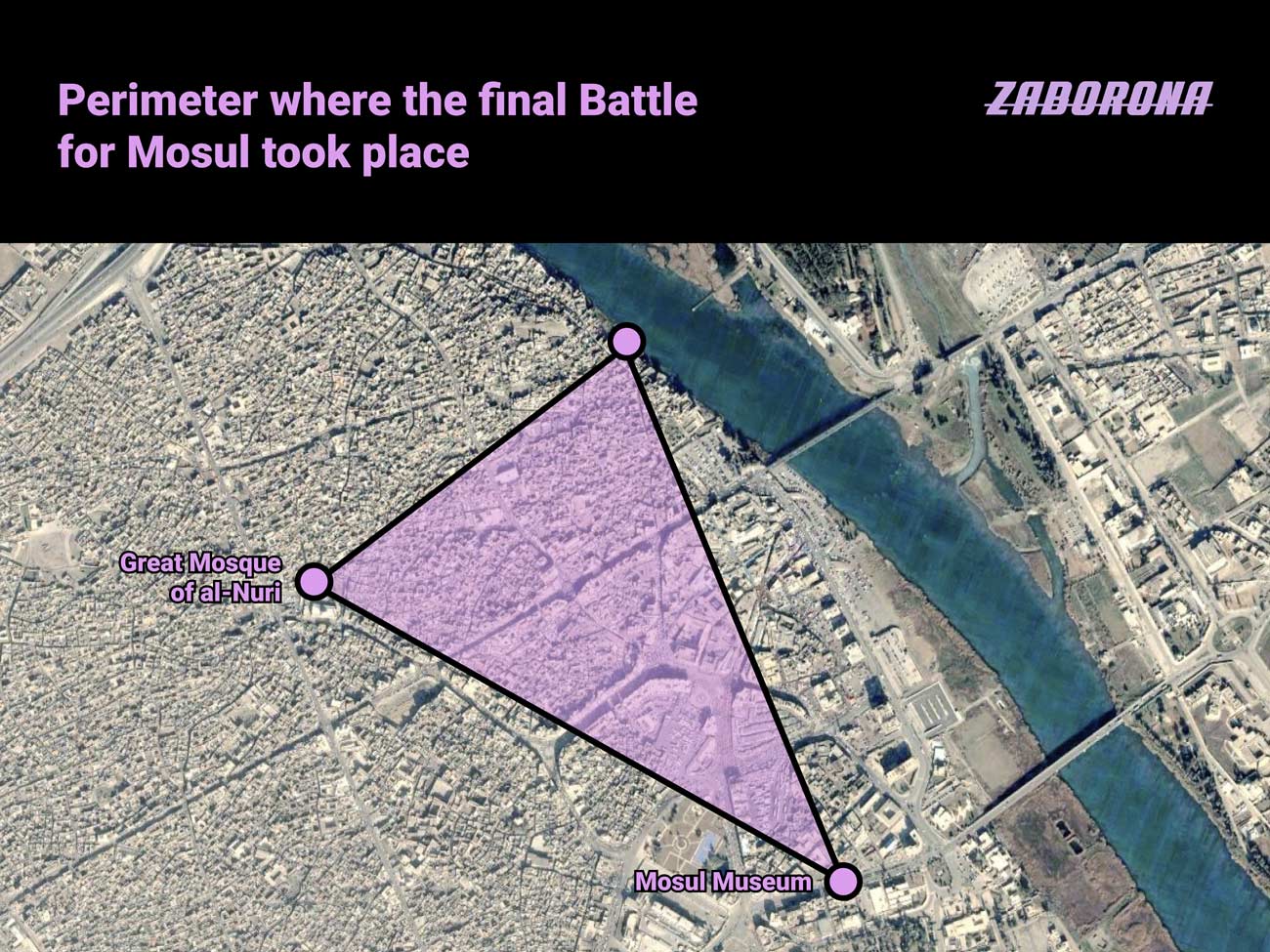

In March 2017, as a reporter for Hromadske, I went to Iraq to see with my own eyes how the fight against the Islamic State was going. One of the critical points for which there were long battles was the Mosul Museum. It kept unique sculptures and archaeological finds from the times of Mesopotamia. When the Islamic State seized Iraq’s northwestern territories, the militants began to destroy these cultural monuments. They turned the museum into a printing press for propaganda newspapers. In March, the museum came under the Iraqi army’s control, but was still fired upon by militants from blocks across the road.

It was only three years later that I learned that Khadija and her boys lived not far from there at that time.

“We were constantly transported in cars,” Fatima recalls of the last months of her life in the old part of Mosul. “Usually, a man came [into the house] and said: get ready, we are evacuating, the Iraqi army is close. And out of fear, we packed up and fled because we were so afraid to see the soldiers. We were told that they were shooting everyone and raping women. ”

By the end of April, the families of the militants were living in the old town. The houses there are closely adjacent to each other, so close that cars cannot pass through the streets, and it is only possible to get around on foot.

“We were told that military equipment would not pass through these narrow streets, so it was safer for us there,” says Fatima. “But instead, they were constantly launching rockets.”

In the last two months, the militants moved along a very narrow perimeter: from one point to another was a 15-20 minute walk. The army gradually drove them to the river.

“In late June, early July, they began to push us deeper,” recalls Fatima. “And at the very end of the special operation, we already occupied the last blocks near the river.”

Meanwhile…

Every day Tanya wakes up with a question: could her daughter and grandchildren have survived?

The maps of the military operation published by the Iraqi authorities and the data of the UN mission show that most of the destruction during the liberation of the old part of Mosul occurred at Bab al-Tawb and at the symbolic center of the old city: the al-Nuri mosque, in which ISIS’ Caliphate was proclaimed in 2014. It was demonstratively destroyed on June 25, about the time when Fatima last saw Khadija. The neighborhoods on the banks of the Tigris were much less damaged.

An-Nuri Mosque in 1932. Photo: American colony photographers / Wikimedia

An-Nuri Mosque in 2018. Photo: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid / Flickr

The militants did not release residents from their neighborhoods under threat of murder. Families of foreigners were of special value to them, so they were constantly moved to the most protected places, but they were forbidden to leave the Islamic State’s territory.

Vera Mironova, a researcher at the International Security Program at the Belfer Center (Harvard Kennedy School), who oversaw the Mosul operation from start to finish and knew in great detail how the fighting took place, says that despite the encirclement, the military provided the militants with a “green corridor” to leave the city. She claims that ISIS has repeatedly taken buses with women and children to Tal Afar, a small town northwest of Mosul, near the border with Syria. This was confirmed to me by one of the women (she asked to remain anonymous), which the militants drove through the “green corridor”.

Those who managed to get to Tal Afar were much more fortunate than those who got to Mosul. At the end of August 2017, the Kurdish Peshmerga liberated part of the city and allowed women and children to surrender. Officially, the Iraqi authorities say that more than 1,400 people have surrendered. Among them were those who had previously lived in Mosul, basically all citizens of the countries of the post-Soviet space. Of the foreigners remaining in Mosul, only a few dozen surrendered.

Fatima says that at the end of July, when the old city was finally surrounded, she was among the few foreign women of the Islamic State who fell into the hands of the authorities alive. They were taken to Baghdad and tried in a local court. Everyone was sentenced to 15-20 years in prison, except for Fatima: she was found guilty only of illegally crossing the Syrian-Iraqi border and was released a year later. The German authorities made efforts to drop the charges against her and return her home.

How many people were killed by the Islamic State in the battles for Mosul is unknown. Vera Mironova says the authorities did not count these losses. She claims that the bodies were taken to the morgue of the city of al-Qayyarah near Mosul, where the air base of the Iraqi army is located. One of the reports from HRW also said that human rights defenders found a mass grave of ISIS supporters killed by Iraqi paramilitary groups in the city.

The problem is also that the Iraqi authorities do not respond to journalistic inquiries and are evasive about the military operation’s results against the Islamic State. And the data that they call often does not correspond to reality. For example, Lieutenant General of the Joint Operations Command Abdul Amir Yarallah told the press that in 11 days of fighting for Tal Afar, the military killed more than 2,000 ISIS fighters and 50 suicide bombers. And the international organization Human Rights Watch has published information that the Kurdish Peshmerga in early September executed more than 400 ISIS members who were caught or surrendered during the fighting in the north of the city. Vera Mironova believes that even these data are far from reality.

If Khadija died, it is almost impossible to find confirmation of this.

But if she survived, where could she have gone?

5. Secret Prisons

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

In October 2020, Tanya and three other women went to a press conference in Kyiv, where she told her story. It was the first time that women trying to get their loved ones back from the camps and prisons in Syria and Iraq had spoken in public. Previously, they silently wrote letters to the Foreign Ministry, the government, and the President’s Office, but this did not work: no one wanted to take on the salvation of the wives and children of terrorists of the most dangerous organization in the world. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs knew about the problem from the very beginning but chose silence. This was repeatedly told to me by the leadership of the ministry themselves.

After the press conference, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs made contact with the women. Fatima Boyko, the leader of a Ukrainian group of relatives of women who want to return home from Syria and Iraq, literally forced officials to tackle the problem. At a closed meeting in the ministry, the women were introduced to the coordinator from the Foreign Ministry and promised that before the New Year, women and children from the Syrian camps of Al-Hol and Roj would be returned. The process had begun.

Tanya felt aloof at this meeting. She was the only one there who for several years had had no connection with her family or even a hint of where to look for them. The ministry told her: write a letter, tell your story, and then we’ll see. She was indignant because she had already written the same thing so many times, but she did. The request was sent to the consular service in Baghdad, and there they promised to send requests to all prisons and orphanages in Iraq.

But there are secret prisons in Iraq where no inquiries will reach.

In November 2020, the UN announced that it counted about 420 secret prisons in Iraq where thousands of people were illegally being detained. The organization drew attention to the fact that the problem has not been solved for years and the situation has become especially aggravated since the defeat of the Islamic State. Many people disappeared during the fighting, and later a ransom was demanded from their relatives for their release.

These disappearances are associated with “popular mobilization” groups or militias: in Arabic they are called al-hashd al-shaabi, or simply Hashd. They are mainly composed of men belonging to the Persian Sistani ethnic group, which associates itself with part of the people of Iran and Afghanistan. Most of them are Shiites, and the fight against the Islamic State and Sunni Muslims for them is “a godly cause.” The Hashd are formally controlled by the Iraqi National Security Adviser and are paid by the state. Officially, there are about 140 thousand members of such groups in the country, and they are virtually uncontrollable.

In the spring of 2017, the human rights organization Human Rights Watch accused Hashd of mass extrajudicial executions. Around the same time, it became known that since 2014, about 4,000 people have disappeared in Iraq: this was linked to secret prisons that Hashd controls. Iraqi parliamentarian Zana Said admitted that there are streets in Baghdad that even MPs would be unwise to walk on, since “the government does not control such streets, and groups of criminals attack citizens, kidnap and kill anyone they want.” And in November 2020, HRW again drew attention to the fact that Hashd is behind most of the country’s disappearances.

Researcher Vera Mironova says that throughout the military operation in Iraq, the presence of Hashd groups became a problem for the regular troops. In the disappearances, human trafficking, and extrajudicial executions of ISIS members and people who were mistaken for enemies, Hashd was mainly to blame. Still, the shadow fell on all the forces of the special operation.

Meanwhile…

Rushena Takhirzhanova, a Ukrainian woman, came to surrender to the authorities in Tal Afar, along with hundreds of other families living under the rule of the Islamic State. The part of the city where they left was under the control of the Kurdish Peshmerga army. Most of the women with children were then handed over to Baghdad’s authorities, but it happened differently with Rushena: she was kidnapped. Rushena and two dozen other women were put on a bus and taken to Bartalla, a small town located between Mosul and Kurdistan’s Erbil. There is a prison for the Hashd group led by Abu Jafar.

“They kept us in the house for almost six months and practically did not take us out for a walk,” Rushena says. “I managed to bribe one soldier and get in touch with my family. My mom and sister made a fuss, appealed to the authorities, and I was transferred to a prison in Baghdad. ”

Rushena claims that Abu Jafar intended to sell her and other women in a secret prison into slavery in Iran.

“Iranians came to us and said: choose Iran, this is a good country, also Islamic,” Rushena recalls. “They said they would pick us up in groups of 20 women.”

A person who has researched human trafficking between Hashd groups and Iranian citizens asked me not to be named because he considers this topic dangerous for those who study it from the inside. This source believes that since the military operation against the Islamic State, the Khashd groups have established channels of human trafficking with Iran and Afghanistan. Many women and adolescents who lived under IS and fell into the hands of such groups later ended up in military camps in these countries. It is almost impossible to get them out of there: none of them have documents and no connection to home, and their relatives do not know how to look for them.

6. Emptiness

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Tanya and I are drinking coffee in her kitchenette on the outskirts of Kharkiv. Outside the window are lonely bare poplars; there is a lemon petrified and blue with mildew in a teapot. The table is littered with photographs of children: most of them are photographs of the eldest grandson from birth to the last pictures that Natasha sent at the end of 2016.

“Look, you can see that he has a strained smile here,” Tanya laments. “She told him to smile. And he smiles, but it is clear that it is not a genuine one.”

Tanya drinks a couple of valerian pills and brews herself granulated Nescafe. She will then drink a few more cans of an energy drink.

In the evening Tanya has to go to work. She works the night shift as a cleaning lady in a convenience store. After 12 hours of work, early in the morning, she returns to her tiny cold apartment, goes to bed, and sleeps until evening. Sometimes she spends more than 30 hours on her feet. She never takes a day off: she tries to occupy herself to the fullest, so as not to think about anything. And they pay pennies in the store, so you have to take more shifts in order to earn at least something.

Since her daughter and grandchildren have disappeared, Tanya’s life has become an exhausting, devastating routine. Long searches have led nowhere: there is not even the slightest clue. There are only fading memories and photographs from four years ago.

“I blame myself for not stopping her from leaving,” says Tanya. “I am a bad mother, I had to prevent that man from breaking my daughter’s will. I should have hid her somewhere.”

But still…

In the four years that have passed since Natasha ended up in the Islamic State, Tanya did not receive any sympathy or participation from the people she addressed. The special services have tried continuously to get rid of her, and the government remains silent. Once, she managed to break into the circle of President Volodymyr Zelensky at a meeting with the Kharkiv governor. The meeting was short and fruitless. Tanya says they hinted that the return of loved ones from those regions would cost her “a sum with six zeros.”

“One woman, they say, paid that kind of money, and they helped her to get her relatives out,” says Tanya. “But she sold the apartment for this. And I have nothing to sell.”

Ukraine has never officially recognized that its citizens left to fight for the Islamic State. This topic is a taboo for Ukrainian officials. That is why the Foreign Ministry reacted quickly to the women’s statement at the October press conference: they didn’t want to earn a reputation for being completely indifferent.

But this is not the case everywhere. Kazakhstan is an example for everyone who is faced with the problem of finding and returning relatives from the Islamic State. Thousands of Kazakhs left for Syria and Iraq to fight on the side of the terrorists. Nevertheless, in 2019, the government began to conduct Operation Zhusan to return its citizens from prisons and camps. During the year, more than 600 people were able to return, including 407 children. And at the end of 2019, the special operation “Rusafa” took place, when 14 Kazakh children were returned from a Baghdad prison where their mothers served their sentences.

The leader of the Kazakh group of parents, Botagoz Makhatova, says that at first when it became clear to what extent the war in Syria and Iraq was gaining, everyone was frustrated and did not understand what to do. Her son left for Syria in 2013, had a wife and children there but died three years later during the shelling. She wanted to rescue her daughter-in-law with her grandchildren while they were still alive. Together with other parents, she turned to the Minister of Religious Affairs of Kazakhstan. He agreed to help and organized a series of “round tables” where parents talked about their relatives’ fate and raised the issue with President Nursultan Nazarbayev. He told him that his citizens were in danger and he could leave them there.

Parents, together with government representatives, created a working group: they drew up official letters, return lists, made visual materials in Russian and English to distribute wherever it might be useful. As a result, they were heard: Kazakhstan agreed with Syria on the return of its citizens. Makhatova’s daughter-in-law returned home with her children. After their return, several women were sentenced to prison terms for propaganda, but most of those who returned went through a course of rehabilitation.

“We asked the government to help us and in return promised that we would take responsibility for them until the end of their lives, that they would undergo rehabilitation, and then we would raise them,” says Botagoz Makhatova. “The following rule applies here: if parents do not take on such responsibility, then the state will not take it on either.”

Nevertheless, about a hundred Kazakh families still do not know where their relatives are: the last time their children contacted them from Iraq was in early-mid-2017, around the same time as Tanya’s daughter. Most of them were in Mosul, some in Tal Afar.

7. One Boy

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

I show Tanya a photo that I found at a news agency: a boy is squatting against the wall. He looks about seven years old. He looks away, his index finger thoughtfully resting on his chin. On his feet are the wrong size slippers. Around him are dozens of women dressed in black niqabs, completely covering their faces, and many other children of different ages.

This is Tanya’s grandson.

At least he looks exactly like him. The picture was taken on August 30, 2017 in the Al-Ayadiya area in the north of Tal Afar. In this place, more than 1,400 women and children from the Islamic State came to surrender over the course of three days, from August 28 to 30.

Tanya saw this picture before, but, she says, had not paid any attention to it.

“I searched with my heart and thought that he was not mine,” she admits. “I didn’t look at the details.”

I show her the details: here’s a hairline like her grandson’s. Here are the matching earlobes. Here is a curl on the forehead. The same eyes and face shape. The same hollow on the neck. The same height, the same age.

There is also a short video: it shows how a boy, looking at the camera, is chewing something, probably food distributed to children by international volunteers.

“But the little one is not next to him,” says Tanya. “And his mom is not there,” I say. “But at least now we know that your oldest grandson is alive.”

“Now our task,” I say to Tanya, “is to find out where the grandson was sent after Al-Ayadiyya.” Tanya agrees.

“Listen, did I tell you my dream? She says suddenly. “It was so real, colorful, even with smells. Let me tell you about it.”

8. Tanya’s Dream

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets Photo: Snezhana Khromets

Photo: Snezhana Khromets

“I’m standing on a cobblestone road. It’s summer, the weather is warm, trees are green. There are houses, outdoor tables, and plates. There are men and a lot of goods.

I stand there, but I cannot understand where I am, as if suddenly appearing there. And I hear: ‘Young woman, come here, buy something.’ And in my head, I think: ‘Oh, they know Russian. I approach three men and show them a photo. The photo shows my daughter and grandson. I tell them that I have lost my daughter and grandson and ask them if they have any information that might help me. They carefully look at the photograph, then turn away and begin to speak their own language; they no longer understand Russian. And I understand that they know something, but they will not tell me.

And so I walk along this road. It’s a village. On the Internet, I saw houses in Syria and Iraq that are similar; the land is like in the Syrian and Iraqi deserts.

I see my daughter is standing nearby. I tell her that I’ve been looking for them. I ask about my grandson, and she replies that he is eating. I suggest we go home. And we walk back along the coast: the mountain to our right, and the body of water to our left.

And then two huge trucks drive into the water, men with dogs come out of the trucks, dogs on leashes, on chains, are brought in our direction. And out of nowhere, there is a vast number of people. Everyone climbs the mountain, including us. We climb, and the earth is crumbling all around us. I hold onto my grandson, I feel his weight. We’re running, everyone is running, the earth is crumbling, there’s no end to it. Someone falls into the water, splash! And the dogs are on the attack. Again, someone falls, splash, the dogs attack, and the mountain does not end. We are stuck in one place. I can’t hold back or look down. But I see that the dogs are not attacking people. Instead, they are biting off each other’s skin. The water between the shore and the truck turns black and red like bubbling blood. And suddenly, there is silence.

I turn around: there is no one on the mountain: no people, not my daughter, nor my grandson. I look down: there are dogs, men entering trucks, and the water becomes clear again; the banks are not visible. And I hear somewhere there, behind the water: ‘Maaa-maaa …’ I understand that I need to go there. In front of me are some barracks in the desert. Not a single person. Not a single bush. Not a single tree. I understand that I need to get into the first barracks. But this is a protected area. I find the gate and try to make my way quietly. I turn my head, and there is my grandson.

I grab him in my arms, squeeze him. And I understand that I will not be able to look for my daughter further, I need to carry him out. I hold him close, go to the exit, and I have such a feeling that we are strangers. I look into his face: no, it’s my boy. Then I feel it again, the look of a stranger! Later I realized that I would find him, but he had already lived there for so long, seen a lot of things, and he might not remember me anymore.

I take him out. There is a swing nearby, a shop, a sandpit. I put my grandson on the swing. I say, ‘Take a little ride, right now grandma will be back.’ And I myself go to the first barracks, where there are a lot of girls. The beds are clean, and the girls all look similar; one has her hair wrapped in a towel, as if she has just washed her head, and they are talking about something. I go up to the girl and show her a photograph, and that there is already one daughter, without her son. I show it and ask: ‘Have you seen this girl anywhere here?’ The girl looks at the photo and says: ‘She’s here, somewhere!’ And then I wake up.”

“I had this dream a week or two before my daughter was taken out of Ukraine,” says Tanya. “I told her. But she only said: ‘Mom, you always have dreams about something…’”

It is getting dark outside the walls of her tiny apartment on the outskirts of Kharkiv. Tanya finishes her Nescafe glass and begins to collect the photographs with her daughter and grandchildren into a folder. Soon she will go to work.

Tanya looks out the window at the gray-blue sunset. Somewhere in Iraq, her grandson may be watching the sun set in the same way.

If you know anything about the circumstances of the events described in this publication, please contact the editors. Write to us if you can help us in any way in finding Tetiana’s family or if you want to support her.