Life and Death in Trostianets’: Without Food or Medicine and a Morgue in the Garage

Trostianets’ in the Sumy region became a base for the Russian armies almost from the first days of the war. It is a transit city through which the aggressor’s armed forces advance from the Russian border toward Kyiv. From here, from the yards of Ukrainians, the Russian army is conducting non-stop shelling. At least three civilians are known dead and three men have disappeared without a trace. Russian forces have taken all city busses, destroyed hearses, appropriated people’s cars and cellphones, and occupied empty homes. Journalist Nadia Shvadchak reports for Zaborona exclusively on what life in Trostianets’ has turned into after three weeks of the war.

“They’re everywhere, the entire square near the train station is full of tanks,” says Pavlo Rozhenko, member of the Trostianets’ city council, “ We had neither light, nor water, nor heat, nor Internet – just gas. Sometimes we had telephone connections. Today I managed to escape from this neighborhood with my family. I can see that, in a day or two, there will be a humanitarian catastrophe in this city.”

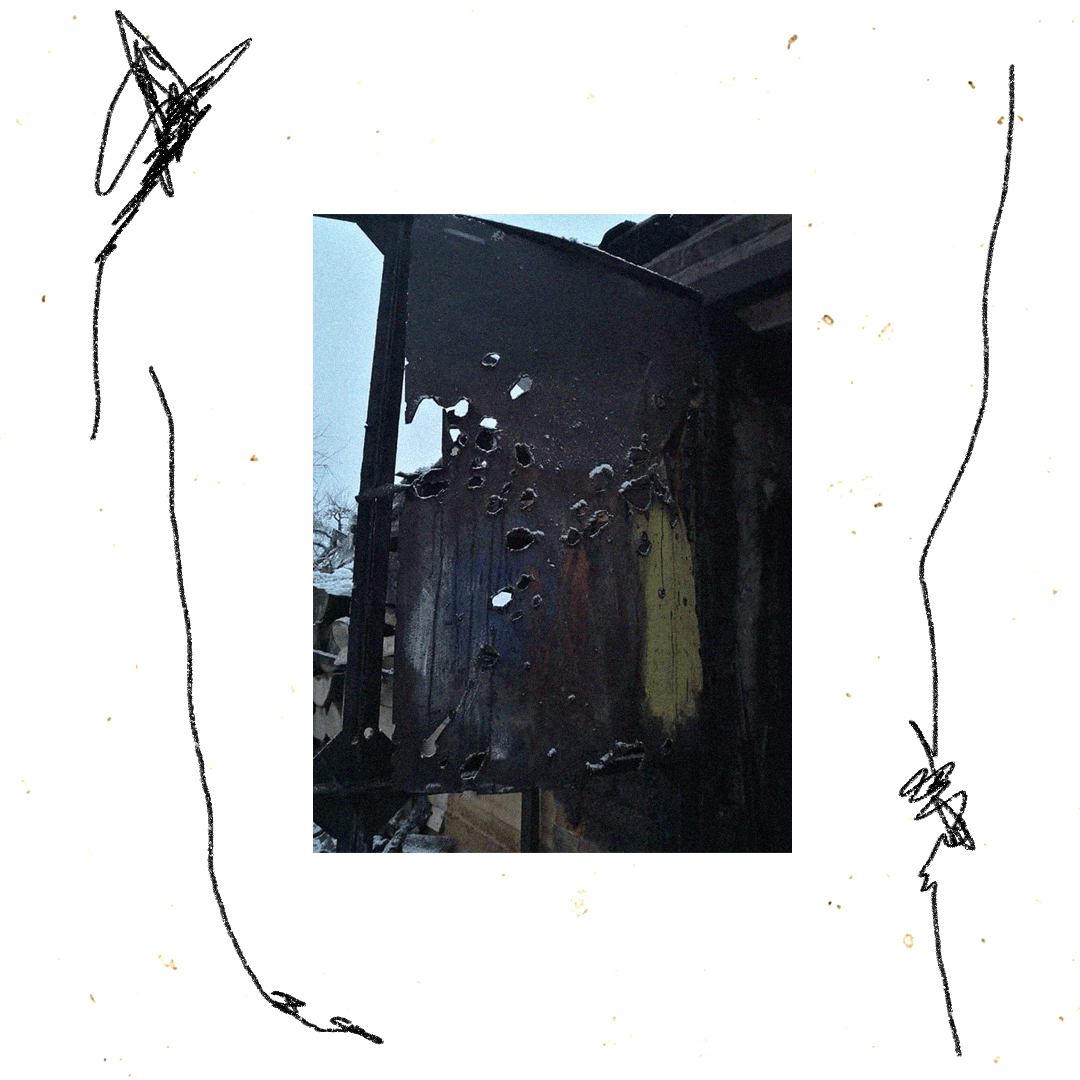

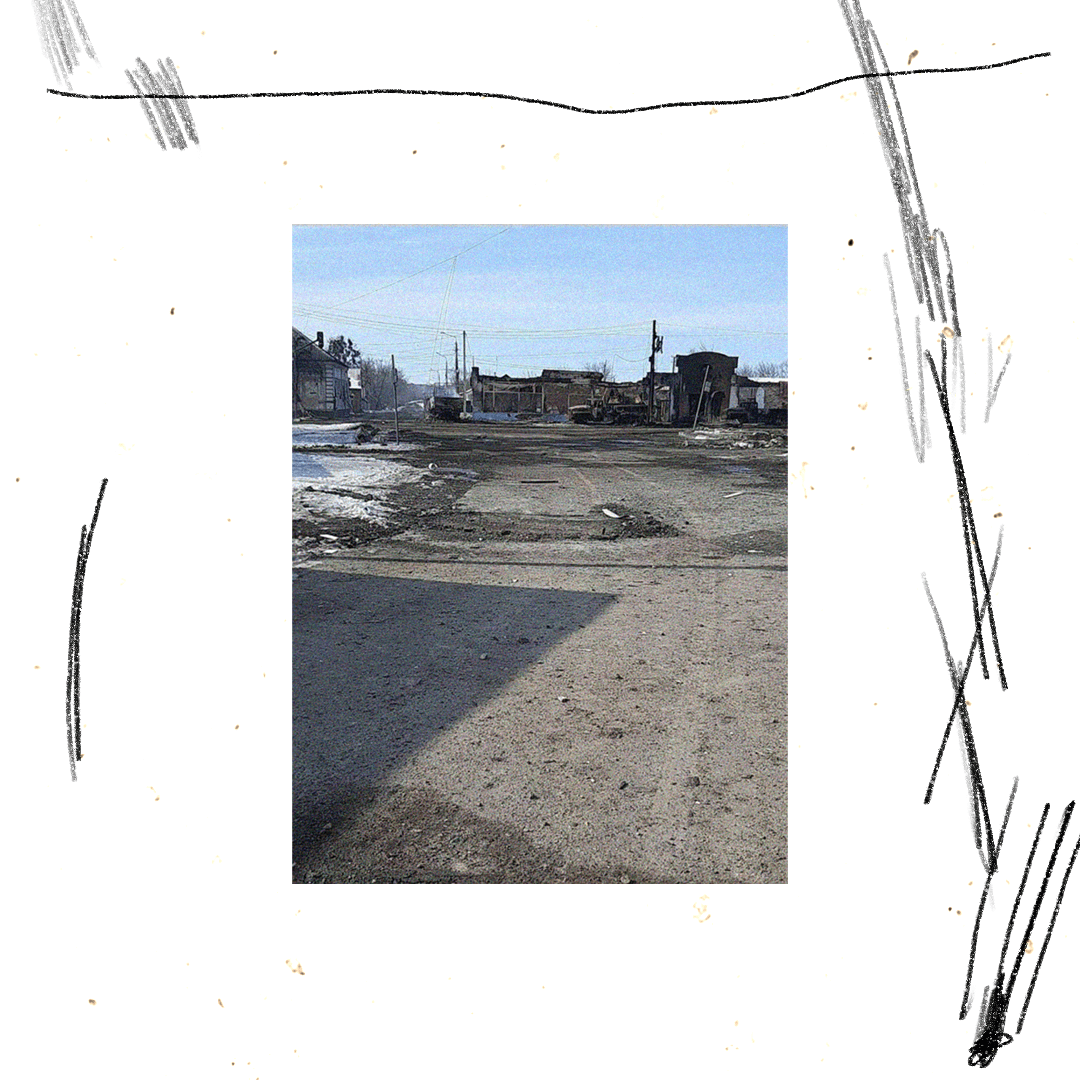

Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo provided by a local resident

Near the train station, a sign appeared: THIS IS RUSSIA.

The city government is not cooperating with the enemy. But people are complaining that the mayor, Yurii Bova, is not in the city. He answers that everyone is working remotely and to work at the council offices is impossible when they are trying to kill you.

They Shoot without Warning

A woman, walking as quietly as possible, her head lowered, tries to avoid provocation. There are other quiet people walking nearby, some of whom wear white armbands. No one has their hands in their pockets – that is forbidden.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

The woman keeps her head down but sees how much enemy hardware there is everywhere and how much enemy personnel is hiding in the back yards. She hears how, at the checkpoints, her neighbors are told to hand in their cell phones and notebooks.

During the green corridors, people were allowed to move from one part of the city to another. Since the beginning of the war, civilians have had only three opportunities to leave Trostianets’ ( according to official reports, as of March 15, 2,300 people left the city).

Otherwise, it is dangerous to move around in the city. People can not reach their relatives or bury the dead. The city of twenty thousand, dissected by many checkpoints, has turned into a list of threats and bans.

“They don’t let anyone go anywhere, people don’t walk, cars standstill. My father used to live near the train station; four Russians brought him here to me,” says Yurii, a resident, “He left his apartment and started arguing – You broke my windows. I can’t live here in the cold, take me to my son – “They brought him here and told us not to walk outside because there were snipers everywhere. They shoot without warning. They killed a taxi driver. They shot a boy who was walking home just a hundred meters from his house. Both of them lay on the street for three days.”

Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo: Тростянець INFO / Facebook

Both of them lay on the street for three days.

There Is Nothing to Eat. We’re Going Now to Shoot the Dog.

Three volleys, eighteen seconds of a piercing whistle. A man covers his head with his arms and counts. He’s standing in his own yard. Above him, a bright blue sky, at his feet, the dusk-covered snowy earth.

“Every day I go to work at the veterinary clinic, “ he says into the phone, “Rockets fly above my head. What can I do? I squat down and pray to God that I don’t get hit.”

The man passes a crater five meters wide and half a meter deep. This is a “GRAD”. He looks at the broken windows of the veterinary clinic. These are automatic queues.

The man counts again. In the seventeen days of the war, seven patients have come to him without animals. He treated splinters, sewed us wounds, and injected antibiotics. “What have we lived to see,” he says, “a vet treating people. Four people have come to me to out their pets down because they have nothing to feed them with.” He sent them away four times, “ Wait, maybe this will end soon.”

A man stands in his yard and says into his phone, “ This is a nightmare here. People are starving. One got a gun. I ask them, “What is that for?” They say, “We’re going to shoot the dog. To eat.”

The wind and explosions howl and a tank drives by the man.

“I have supplies for a month or two. Afterward, maybe I’ll take a gun and go shooting dogs to somehow survive.”

Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo: Тростянець INFO / Facebook

Our Own and Foreign Marauders

“Everything has been looted, nothing works.”

“There is no food. Starvation. People are willing to buy just anything for horrendous sums.”

“We caused our own deficit.”

“We’re ashamed of our own people.”

Residents of Trostianets’ repeat the same sequence of events: first the invaders came and looted the stores. Then our own people came and finished it off. Stores and pharmacies are not working (here and there leftover medicines are being sold off).

“I understand a package of noodles or some canned food, but five boxes [100 pieces] of chocolate or five boxes [180 pieces] of candy bars for one snout?” writes a store owner in her local Facebook group,” and some were even dragging three boxes! And boxes of dish-washing liquid? And why steal a microwave? There’s no electricity anyway! What were you planning to do with nails, building levels, and screwdrivers?”

“We thought you were giving away the goods,” say those who come to pay for the stolen items.

Cameras were working during the looting.

Many of the looters were regular customers of the store.

Half a Loaf of Bread into Your Hand

“We knew that the war would begin and the looting, too,” says Myroslav Shylo, owner of a restaurant in Trostianets’. His brother owns a store in the same building, “That is why, from the first day of the war, we decided to stay here.”

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

When all the stores had been looted, the brothers decided to bake bread.

“We organized a group of people who cared,” says Myroslav, “ Some brought flour, others yeast. We found an electric oven and volunteers who deliver bread, over fields and forests, to the elderly.”

Myroslav’s team is forty-strong and bread is being produced around the clock. When they have electricity, 1,400 loaves are produced daily. When there are interruptions, only half a loaf is distributed per person. People stand in line from 6 am and the line grows longer every day.

Flour supplies are not yet critical but are approaching that status. It is risky to send a car for supplies and to expect to be let through at an enemy checkpoint is not a real option. Volunteers then carry bags through the city on their backs.

But that isn’t their only job.

Today We’re Transporting Flour, Tomorrow It Will Be Bodies

“Yesterday some people dug a hole in the forest and buried a woman because they have forbidden us to bury people in the cemetery!,” says a local man, “and a neighbor of mine lay in the morgue for five days until volunteers came to take her away. No family, no nothing. They just put her in a pit at the cemetery.”

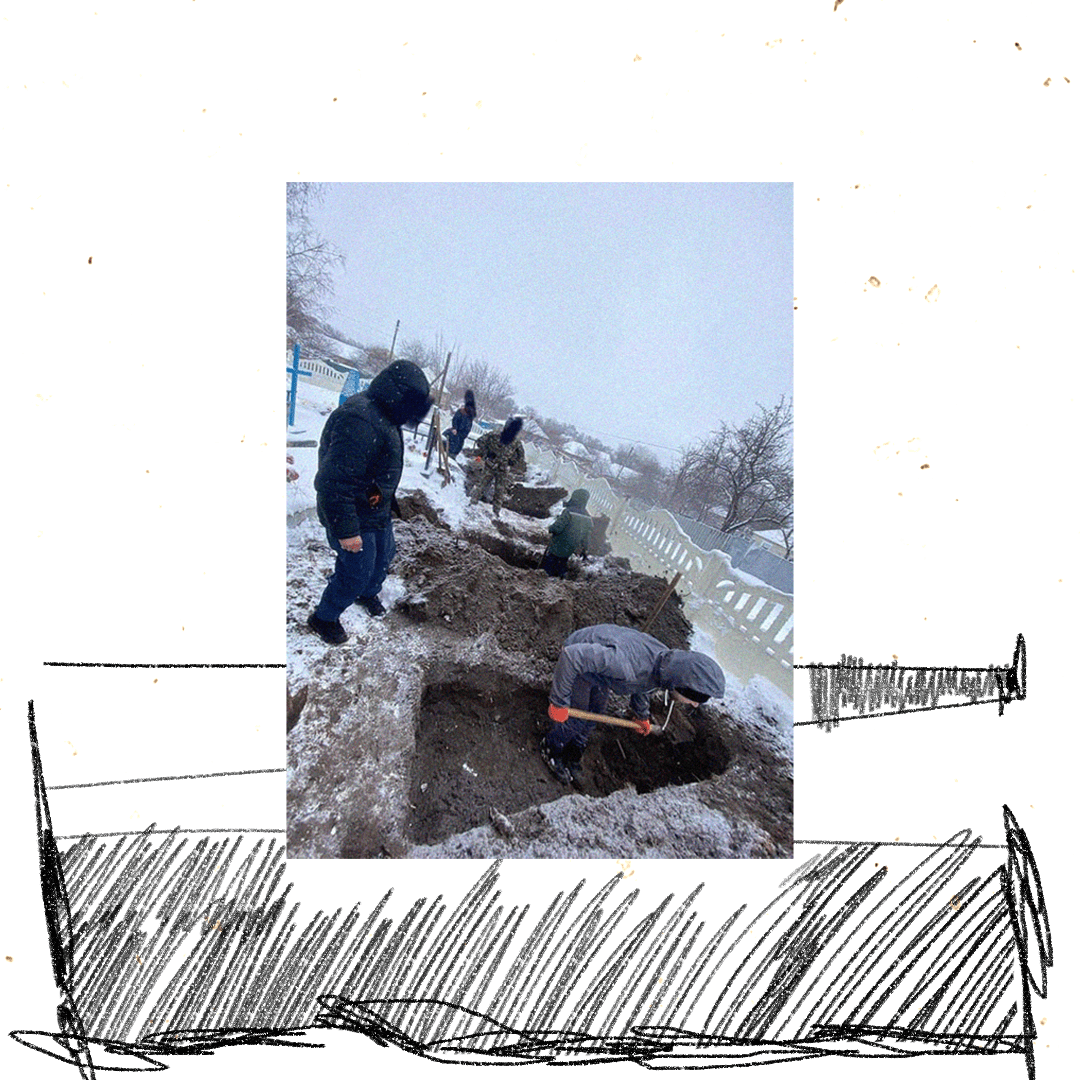

Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo: Тростянець INFO / Facebook

I call a woman who helps with burials in Trostianets’. But she doesn’t want to talk, my questions irritate her. “ I don’t know you,” she says.

She explodes, “Here are your questions! Have we been able to bury everyone? How?! During peacetime, three people died every day. And now three people were killed just at the factory…There were no burials today or yesterday. I look at the list [she sighs]: February 24, four people, February 28, four people, March 4, five, March 6, two, March 7, two, March 8, one, March 10, three, March 11, one. Do we bury only when there’s no shelling? How are we supposed to do that? Is there a planned green corridor? Nothing has been done. I’m waiting for the city council to arrange something. How does a funeral get done? They tell us on what street someone has died. If the Russian army is not there, we pick up the body. If it is there, no one will risk the living for the dead. Do you understand?”

“Today we’re dealing with bread, tomorrow, with bodies, “ says Myroslav Shylo, “ There are many bodies at the morgue and there are about twelve still in their homes. And we only have one car (donated by the city council) which travels at its own risk. And, in general, you know, I’m a musician.”

Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo provided by a local resident

The Way into the Ground

Near the cemetery, there is an enemy checkpoint with one or two tanks, a sniper, or a whole group of the enemy with machine guns. Witness accounts vary. Some say that anyone who approaches is shot. Others say you can get into the cemetery if you ask them.

It seems to be a matter of luck.

Oleh Pavlovych’s body has lain in the garage for ten days. The office of funeral services tells Oleh’s son that it is a great bit of luck. That during the war, there was a case where the female deceased had to lie in her apartment for eight days and there was no air left to breathe. Her son-in-law then put a casket onto a sled and pulled it to the cemetery where they wouldn’t let him in. So he had to carry the body on his shoulder and put it in the casket at home.

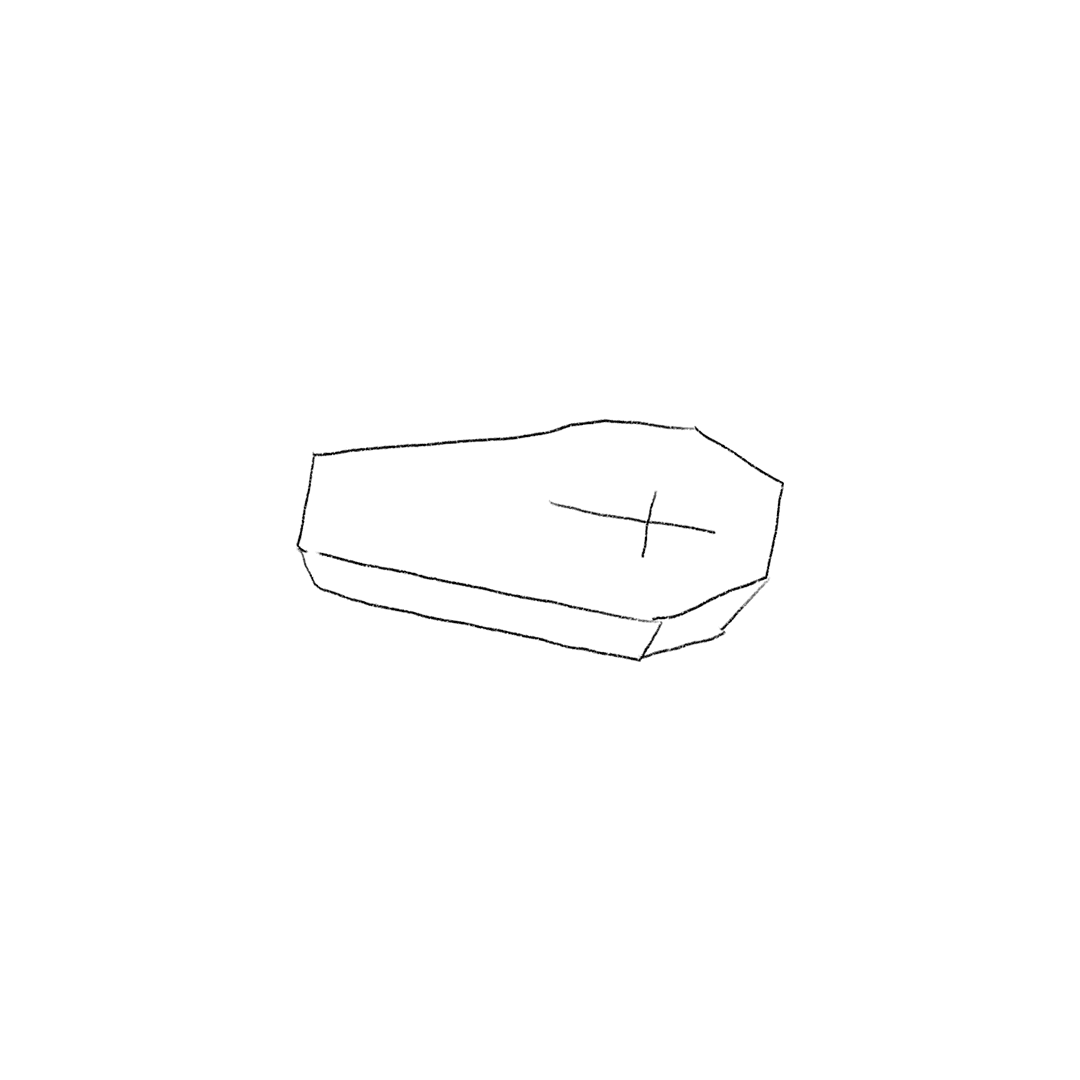

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

Oleh Pavlovych’s body is in a casket. This is also a great bit of luck because when volunteers load bodies into their car, the bodies are not in caskets. That is also how they get buried. “ It’s as if a truck hits a dog that gets buried by the side of the road. A most unpleasant procedure,” says Myroslav Shylo.

Oleh Popovych’s son had to make an effort to put his father’s body into a casket: he had to take his neighbor’s sled, go through ravines, avoid enemy checkpoints, make a hole in the fence to get to the funeral office to pick up the casket (the pickup was pre-arranged), and very quietly get the casket home.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

Now, to get Oleh Popvych’s body into the ground, a hole needs to be dug. His son takes his friends, the sled, and shovels. They head for the cemetery, get in through the hole in the fence, and sneak to his family’s plot.

Then suddenly a soldier with a machine gun is running toward them!

At the moment, they’re not chasing us away,” says Oleh Popovych’s son, “but the coffin has to be transported. That’s complicated because it’s not allowed by car. We can use the sled but the snow has melted on the street and there is no other transport nearby.

“I expect there will be a green corridor to the cemetery,” ponders the soldier. “I can wait a maximum of two days, then I’ll dig a hole somewhere in the yard”