Recently, a petition to grant temporary and permanent residence permits to citizens of Belarus and Russia who lived in Ukraine before the war has appeared on the website of the President’s official representative office. This is a reaction to the decision of the State Migration Service to force some Belarusians and Russians to leave the country, which often does not comply with the law. Zaborona spoke with an activist from Belarus who helped clear the debris in Bucha, and a Russian man who has lived in Ukraine since 2005 and refused to pay a bribe to an SMS officer — both of them plan to appeal the Migration Service’s decision. We also spoke with a human rights activist and a lawyer and asked what foreigners should do to stay in Ukraine.

In December 2021, in Soligorsk, Belarus, a precinct officer inspected Karina Potemkina’s room in detail. Potemkina herself was not at home, so the landlady opened the door. The girl realized that the person was from the police when the landlady told her the guest’s words: “Tell her to stop writing about the government.”

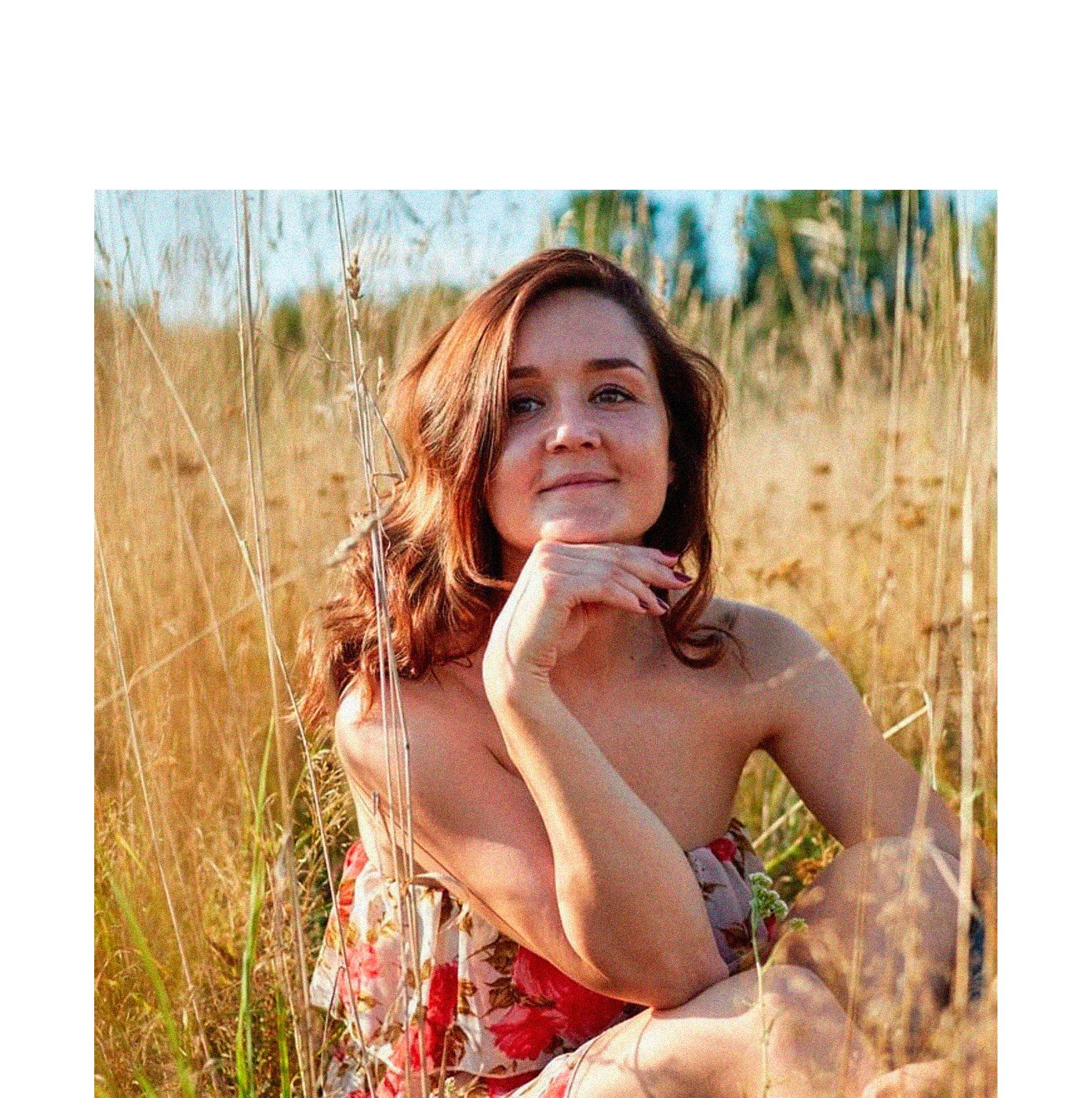

Karina Potemkina. Photo: Facebook

Before that, Potemkina, a furniture sales manager, noticed she had been tailed by policemen. Propaganda media had spread discrediting information about her because of her correspondence with political prisoners, criticism of the authorities on social networks, and participation in rallies. In our conversation, she says that she has to talk about it “in order to maintain communication: in Belarus, half of the country is in jail, and the other half is guarding.”

After the precinct officer’s visit, familiar human rights activists said that Karina has 1-2 days to escape. One of them added: “Throw away the SIM card and run.” Several friends were sure that she might be arrested. Like many Belarusians before her, Potemkina left the country through Russia and then crossed the border with Ukraine on foot. There she was picked up by a driver who was going to Transnistria through Kyiv.

Shortly before the start of the war, Potemkina moved into an apartment in Bucha with seven Belarusians. “In the first month of the war, I saw an announcement that the Bucha City Council was looking for volunteers for the call center. I said I was from Belarus,” says Karina. “We don’t care where you’re from, as long as you’re ready to help,” they answered. Karina received several dozen, and sometimes a hundred calls per day: Ukrainians from Europe called to find out if their relatives were alive, people from Bucha asked about the blackout, and sometimes they asked for psychological help – for example, they said that they were afraid of Kadyrovites. “At night, during the explosions, I came out of the basement to catch the connection to answer the calls.”

-

Illustration: Kateryna Kruglyk / Zaborona

Many Ukrainian and foreign media have written about Potemkina’s volunteer assistance. She was one of the most active organizers of debris removal. Karina remembers many residents of Bucha – living and dead – by name and patronymic. One gets the impression that she is familiar with the residents of several streets, and that everyone knows her. For her activities, the woman received recommendations and certificates from the Bucha Council, the Student Society of Lviv Oblast, and the Spivdiya humanitarian aid platform, which cooperates with the President’s Office. But in a few months, Karina will receive another document and a stamp on her passport — both of which will mean that the Belarusian must leave Ukraine.

***

Belarusians have the right to stay in Ukraine for 180 days. If they plan to extend their stay, they should apply to the State Migration Service (SMS) to obtain a temporary (and after three years – permanent) residence permit, or, if the first option is refused, to obtain the status of a political refugee. Belarusians can also receive the status of a person in need of additional protection with the help of the Right to Protection foundation. However, according to Potemkina, it was no longer working when she arrived.

Currently, many Belarusians are faced with the so-called “Trap-22” – a set of rules that contradict each other. During the full-scale war — probably for political reasons — many Belarusians were denied temporary residency. In this case, they have the right to apply for asylum as citizens of a country with an authoritarian regime and repressive social mechanisms. Asylum applications are no longer accepted. In such a case, the guarantor of their rights should be the country of origin – the same one from which they were forced to flee.

Potemkina faced the same problem. She decided to contact the service in the first weeks of her stay in Ukraine, but her acquaintances informed her that the SMS would not deal with her case since she is a citizen of the aggressor country. The war began, the State Migration Service stopped working, and during this time many Belarusians came to the end of their stay in the country.

In a message on social networks dated April 14, the State Migration Service said that citizens of Belarus who did not have time to legalize their stay in Ukraine or did not update their temporary residence permit will not bear administrative responsibility for the inability to extend the period of stay – the service takes into account the suspension of work in the first months of the war.

On June 1, the SMS had begun accepting documents from citizens of Belarus. “I heard that they will start accepting documents. On June 6, I sent a request for the processing status of my documents regarding the legalization of my stay – I did not receive a response,” Potemkina says.

A few days later, she went to the SMS offices at 10 Bohdan Khmelnytskyi Street and 3 Olhynska Street. In one of the departments, an employee took the documents but ignored the package with recommendations and diplomas about volunteering, which testify to Potemkina’s pro-Ukrainian position. The service informed her that she should return in two days regarding some paperwork with her passport and some other papers. Upon returning, Potemkina saw in her passport a stamp on the forced return to the country of origin or any third country before July 15.

“We ran after this worker all over the SMS,” says Karina. “We said: “Take this, take, look at this [documents on volunteering and recommendations of the Bucha Council]. Everything is here. They testify that I am not an enemy of your country. It says here that I am a good person.”

***

Anisia Kazlyuk, a Belarusian activist and human rights defender, has been in Ukraine since August 2021. July 14 is an important date for her. This is the anniversary of the detention by the Belarusian police of employees of the Viasna human rights center, where the girl worked. “I left the country because the investigators were interested in my activities in this organization.”

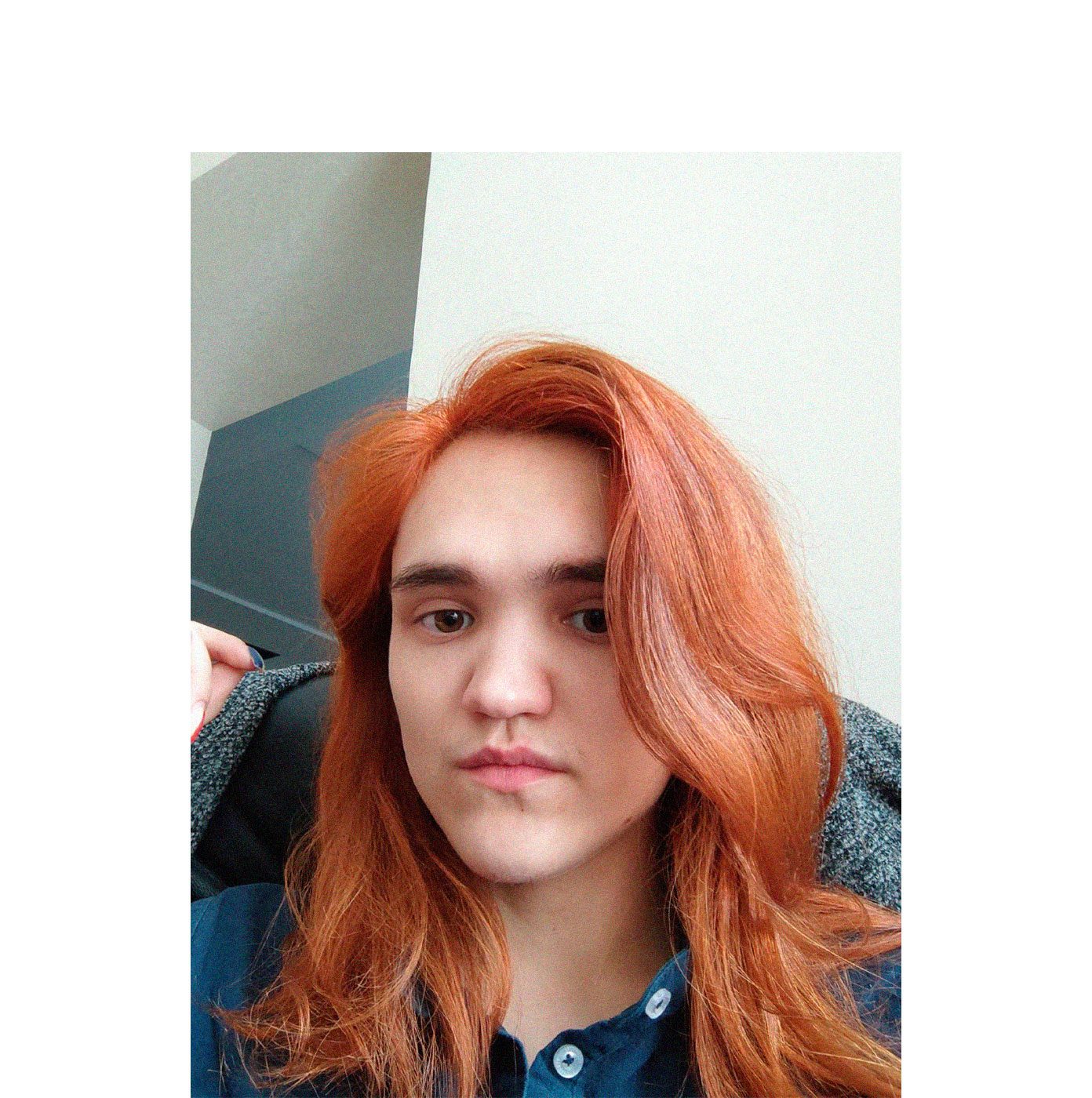

Anisia Kazlyuk. Photo courtesy of Anisia

In January, Kazlyuk collected documents for legalization at the Migration Service. The activist received a passport with an extension of stay until April the day before the war. In March, she again applied to the Migration Service but was informed that due to the lack of access to the registers, documents are currently not accepted from Belarusian and Russian citizens. Then they were not accepted without any reason or references to changes in regulations due to the war.

Kazlyuk is now actively monitoring cases of forced return of Belarusians. According to her, many Belarusians found the same stamp on their passports. And on July 1, employees of the Migration Service reported that foreigners must pay a fine for overstaying, which contradicts the service’s announcement from April, according to which the agency removes administrative responsibility from them.

After paying the fine, the SMS collects the documents, after which it returns the stamped passports. “The migration services operate according to pre-war rules,” explains Kazlyuk. “The overstay requires a stamp, which indicates the need to leave Ukraine.” Potemkina cites the example of Denys Dashchinsky, one of the 43 Belarusians who have been forced to leave Ukraine since the beginning of the year because of a stamp: “The border guards informed him that the stamp is equivalent to deportation. You can try to return in 90 days. It is not a fact that they will let you in.”

Anisia says that in her human rights practice there is already one positive case of prevention of forced return. In order not to receive a stamp, you must come to the Migration Service with a representative of a public organization entered in the register of organizations that can accept foreign volunteers. “You will receive two fines: on the organization for cooperating with an illegal migrant, and on yourself as a person who is in the country illegally.”

But there are cases when a person receives a refusal to extend a residence permit. “Rejection is more often verbal,” says Anisia. “You have to submit a written application for refusal, but sometimes they just don’t want to accept it. Or you should ask for a written answer, which would certify that you were refused to accept the application – this will be a reason to apply to the court.

-

Illustration: Kateryna Kruglyk / Zaborona

According to Kazlyuk’s experience, the only available mechanism that can help Belarusians in case of receiving a stamp is the court. During the hearings, the return process is suspended pending a decision, which can take up to two years, subject to appeals.

Many Belarusians are afraid to go to the Migration Service because they worry that instead of legalization their passports will be stamped. Some are afraid to go to court and leave the country. “Ukrainian lawyers claim that 90% of cases against the Migration Service are won in favor of the applicant,” says Kazlyuk. “But it should be understood that Belarusians do not trust the judicial authorities because of Lukashenko’s destruction of state institutions, and are afraid to turn to them even in Ukraine, where they still work.” The day before the conversation with Anisia, the editor of Zaborona spoke with Potemkina, who, in fact, illustrates Kazlyuk’s comment. Potemkina says she does not want to sue: “Your country is at war. I am ashamed to do this”.

Not all Belarusians dare to speak about oppression in the SMS. But Kazlyuk emphasizes that this should be done, because civil institutions work in Ukraine, and people’s moods and resonance can influence decision-making by the authorities. Anisia also overstayed in Ukraine due to the suspension of the work of the SMS, but she actively wrote about her case on social networks. According to Anisia, her case is perhaps the first in Kyiv when a citizen of Belarus was not stamped and fined for overstaying in the country, due to a great response on social networks.

Anisia adds that for Belarusians, Ukraine is like a breath of fresh air: nightmares stop here, and a police officer does not resemble a terrorist (although it takes time to get used to the fact that he is not going to beat you for rallying with a poster). “But when Belarusians here again face the same kind of repression, it feels like a “hello” from home.”

***

Former President Yanukovych hangs on a rope. In addition to the noose around his neck, there is a sign with the inscription “Butcher” in red letters. A dozen needles are stuck in Putin’s face and head. Next to it is written: “Putin, go back to hell.” Both posters were made by Russian Andrey Sidorkin. The first is to commemorate the death of the Heavenly Hundred, and the second is to condemn Russia’s occupation of Crimea. With them, he went on a picket at the embassies of the Russian Federation in Laos and Vietnam.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruglyk / Zaborona

Jazz musician Sidorkin has been living in Ukraine since 2005. He participated in Euromaidan, donated blood for ATO fighters, and went on humanitarian missions to Donbas. At the beginning of the full-scale war, Sidorkin tried to get into the Territorial Defense and, as he claims, visited the Military Commissariat five times – all times in vain. “I tried to join the ranks of Azov. I walked from the Polytechnic Institute to Svyatoshyn, because the subway was closed,” says Sidorkin. “They promised to call back, but they didn’t. I tried to join the “Sonechko Zakarpattia” battalion. But acquaintances said that because of my passport, the mobility of the group where I could serve would decrease: at every checkpoint, because of my documents, we would be detained for a detailed check – that’s why no one wanted to mobilize me.”

Andrey Sydorkin takes part in the action “Russian intellectuals donate blood to the Ukrainian military”. Photo courtesy of Andrey

For the first ten years of his stay in Ukraine, until 2014, Sidorkin went to Gomel once every three months to update his status of stay – this is called a visa run. After the war in Donbas, this was no longer possible. Sidorkin lived on a temporary residence permit due to his marriage. Having been married for two years, he received a permanent residence permit. But he lost it together with his wallet in a supermarket – the musician believes that the things were stolen.

At the beginning of April, the man went to renew his passport – before that, the Migration Service did not work. “There, I had a 10-minute interview with an employee of the SBU, who emphasized that my case would be dealt with harshly.” In three weeks, Sidorkin received a verbal refusal to stay. On June 4, he received a decision to cancel his emigration permit and passport.

Sidorkin’s lawyer Artur Skrypnyk reads the header of the document that came to the Russian by mail: “The document is called “Decision on refusal to issue a permanent residence permit.” In the cap, where the name of the body should be, it is indicated: “Administration for Temporary and Permanent Residence of Foreigners and Stateless Persons of the Head Office of Central and Interregional Administration of the State Migration Service of Kyiv and Kyiv Region.”

Skrypnyk adds: “The fact is that there is no such administration. There is such a department. The first thing a civil service employee learns is how to spell the state body’s name; there could be no mistake. Administration and department are different levels of authority. Even the name is illogical: the repetition of the word “administration”. That is, it is an administration under another administration.” Instead of a stamp, there was a facsimile copy. Skrypnyk explains that documents must be stamped. Only legal entities under private law may not use a stamp, but such a document must be certified with a wet stamp.

Skrypnyk says that he tried to appeal against the document, which was called a “refusal” in the Ministry of Internal Affairs. “In fact, in order not to be accused of counterfeiting in the future – and forgery of state forms and documents belongs to this category – they made a quasi-official paper of refusal,” explains the lawyer. “This document is a farce.”

The SBU employee, who remarked that he would deal with Sidorkin’s case “strictly”, tried to find his fault in the fact that the Russian applied for a permanent residence permit after the divorce. “The right to marry includes the right to divorce. Andrey was married for more than the required 2 years. The law does not stipulate that divorce cancels the right to emigration and permanent residence. This is a discretionary decision, a decision at one’s discretion, which has nothing to do with the legal basis,” says the lawyer. In addition, some Belarusians and Russians are forced to leave the country even though they are married to Ukrainian women and men, which is against the law.

Rally in Vientiane, Laos (2014). Photo courtesy of Andrey

Rally in Vientiane, Laos (2014). Photo courtesy of Andrey

Skrypnyk and Sidorkin are sure that the SMS was waiting for a bribe — the amount was announced through third parties. Andrey and his lawyer tried to make an oral administrative appeal against the refusal to stay because of an employee who “didn’t even want to listen.” This employee was a high-ranking official Dmytro Lemesh – a few weeks ago, he was caught taking a bribe.

Skrypnyk explains: if an administrative appeal is not enough, the only way out is to go to court. This is exactly what the lawyer and his client are going to do. “People are intimidated by the courts. But foreigners should understand that the legal base is on their side,” Skrypnyk assures.

It is known in Russia that Sidorkin has a residence permit in Ukraine. If he is forced to return to St. Petersburg, the airport employees will quickly understand where he came from, despite the connecting flight from another country. “With a high probability, I will have a conversation with an FSB employee at the airport, which I will not go through.” Due to his pro-Ukrainian position, Andrey can be convicted under an article about discrediting the Russian army and spreading fakes.

Skrypnyk claims that Andrey’s case is a personal matter for him. “I believe that in the future there will be attempts to squeeze out Belarusians and Russians, but they will be unsuccessful,” the lawyer adds. “I am thinking about how to unite with other lawyers to make a conveyor for appealing similar cases. I would like the court to get the impression that there will be a reaction to each such case.”