Mykola Matsey was my grandfather. He died in 2011, but I still remember well his stories about his youth. My grandfather told me about working in Germany and Siberia, about imprisonment and returning home. Already in adulthood, I recorded our conversations on a dictaphone, which became the basis of this text. Since 1995, my family has been looking for evidence of his stay in Germany to confirm his status as an Ostarbeiter in order to receive compensation from the German government. While collecting evidence, we found several signed archival photos of my grandfather from Germany, as well as correspondence with people from another, Hitler era. Delving into the biography of an ordinary young man gives an idea of the life of millions of people who were sent to forced labor in the Third Reich, and after the victory of the Allied forces — to Siberia.

In 1941, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. 19-year-old Mykola, the eldest of five brothers, was forcibly deported by the Nazis to Germany for forced labor, along with 2 million other people from Ukraine. Matsey was first taken by freight train along with hundreds of other Ostarbeiters to the city of Hildesheim. From there he was sent to work in a sugar factory located seven kilometers away in the village of Dinklar. He worked there from October 1941 to May 1945.

When issuing documents to Ostarbeiters, the German police warned through an interpreter: “Do not let any of you think of running away or stealing something. We have places where you enter through the door and leave through the chimney.”

Work at the factory

The young man had no professional qualifications. The foreman Konrad Garbs, who always called him “Nikolaus, komma her” (“Mykola, come here”), gave him the skills that became his profession for life. Matsey became a gas welder and performed repair work in the shops of a German sugar factory.

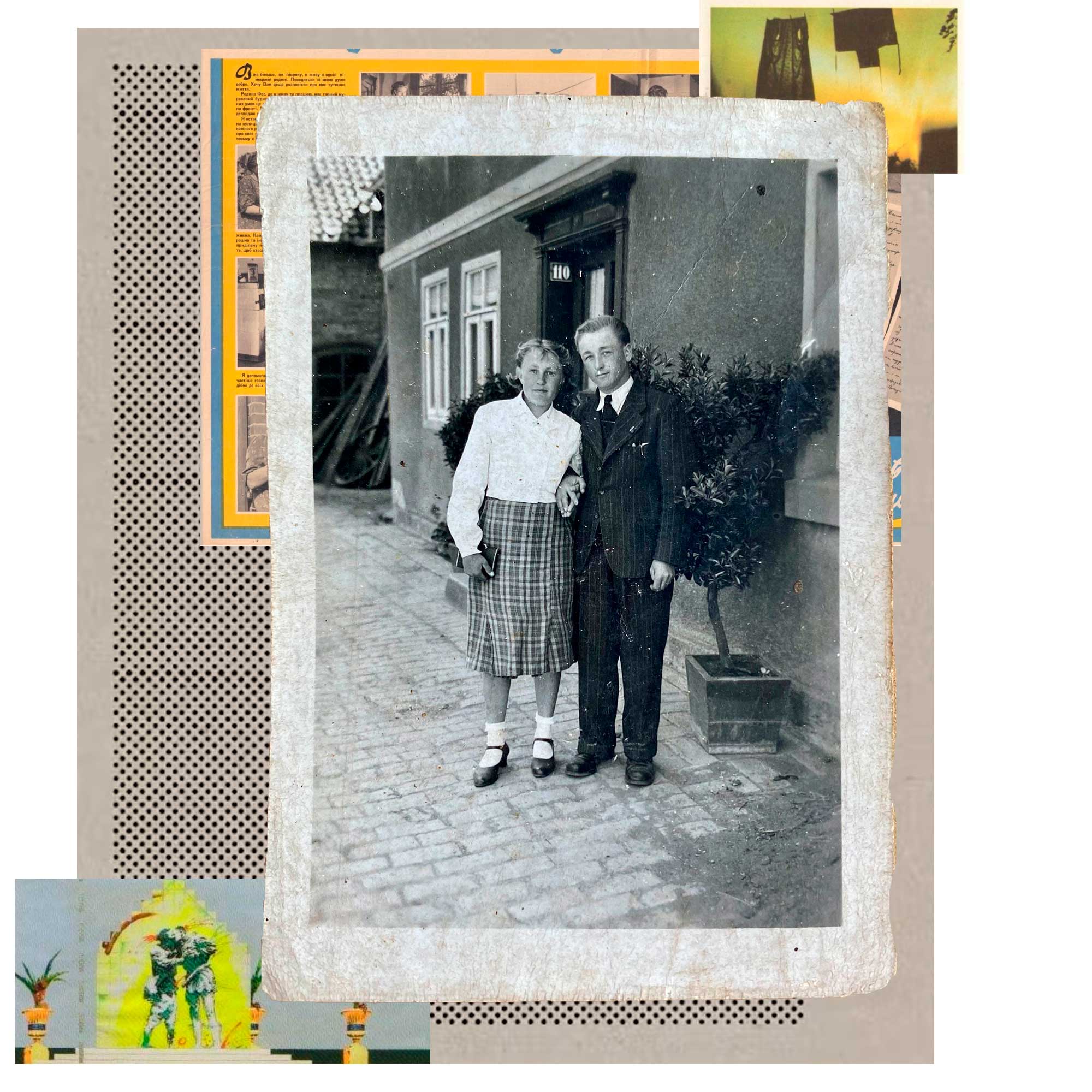

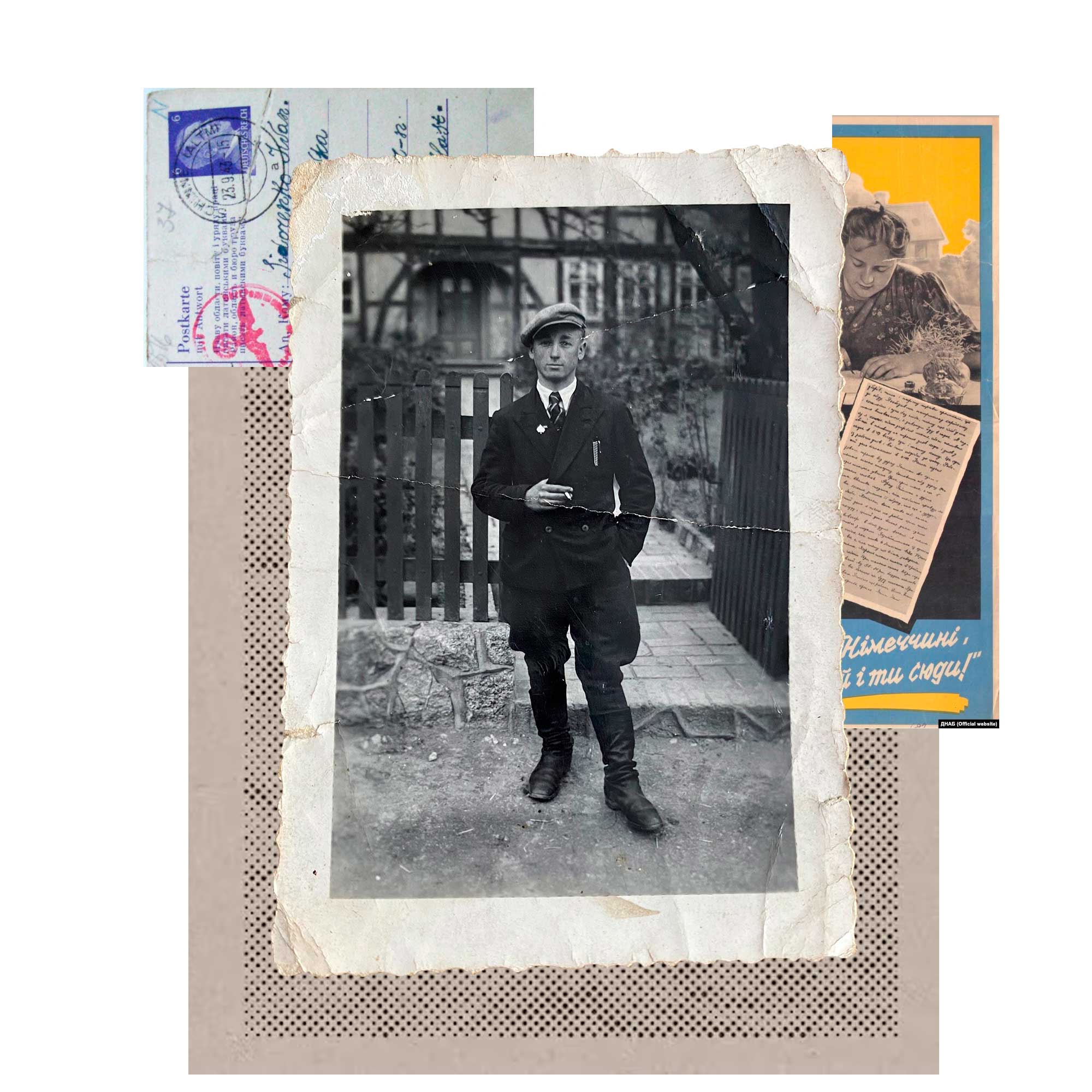

-

Mykola Matsey, Germany, 1942. Photo courtesy of Pavlo Bishko

Mykola’s working day lasted 12 hours, from Monday to Friday. On Saturday, he worked until lunchtime. In Dinklar, Matsey met a policeman, Mr. Hakke. He and his wife lived near the factory, but worked in Hildesheim. “Mr. Hakke knew that I worked at the factory. He called me and asked if I could clean and lubricate his bike,” Mykola recalled.

Matsey repaired the bike and Mr. Hakke liked the work done. In the house where he lived, on the ground floor was his shop, where Mrs. Hakke worked. When Matsey brought the bicycle to the couple, Mr. Hakke was at home, dressed in his uniform and police hat. He invited Mykola into his shop and asked:

– What do you want to buy?

– I have everything, I have bread… “Then he weighed a kilogram of sweets, cookies and gave it all to me,” Matsey said.

-

“Friendly Life in Germany,” 1942. Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo courtesy of Pavlo Bishko, “Light and Shadow” Ukrainian photo art magazine, №1, 1993/Yuriy Afonin

There were many sweets in Hakke’s shop. Sugar beets were brought to the factory by horses, trucks, and tractors. First, the beets were washed with water, cut into strips, and then boiled in boilers. This is how sugar was made.

“It happened that a horse and a bull carried beets from the field in one harness. There was not enough machinery then, horses were mainly used for transportation, but they were also not enough,” Mykola recalled.

According to Matsey’s recollections, Germans in the village worked very unitedly. When it was harvest time, everyone worked. When collecting firewood — all were going to firewood. When a wagon with coal in briquettes arrived, everyone unloaded it together.

-

“Friendly life in Germany”, 1942. Mykola is the second from the left. Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo courtesy of Pavlo Bishko

“Those were difficult times, but I remember with respect these kind people who taught me to work and gave me a profession,” Matsey recalled in 1995 in his letter to the director of the sugar factory (which no longer existed; the letter was sent “blindly”).

You will remember this evening for 45 years

American aircraft intensively bombed Hildesheim, near which the sugar factory was located. Mykola remembered how during the air raid sirens were blaring loudly, and in the city there were signs “Bomben sind schneller, bei Alarm ins Keller” (“Bombs are faster, in case of alarm — to the basement”). During one of the alarms, he barely found a free place in one of the crowded bomb shelters. “And at that time Hitler thought he would conquer the whole of Europe,” he recalled.

-

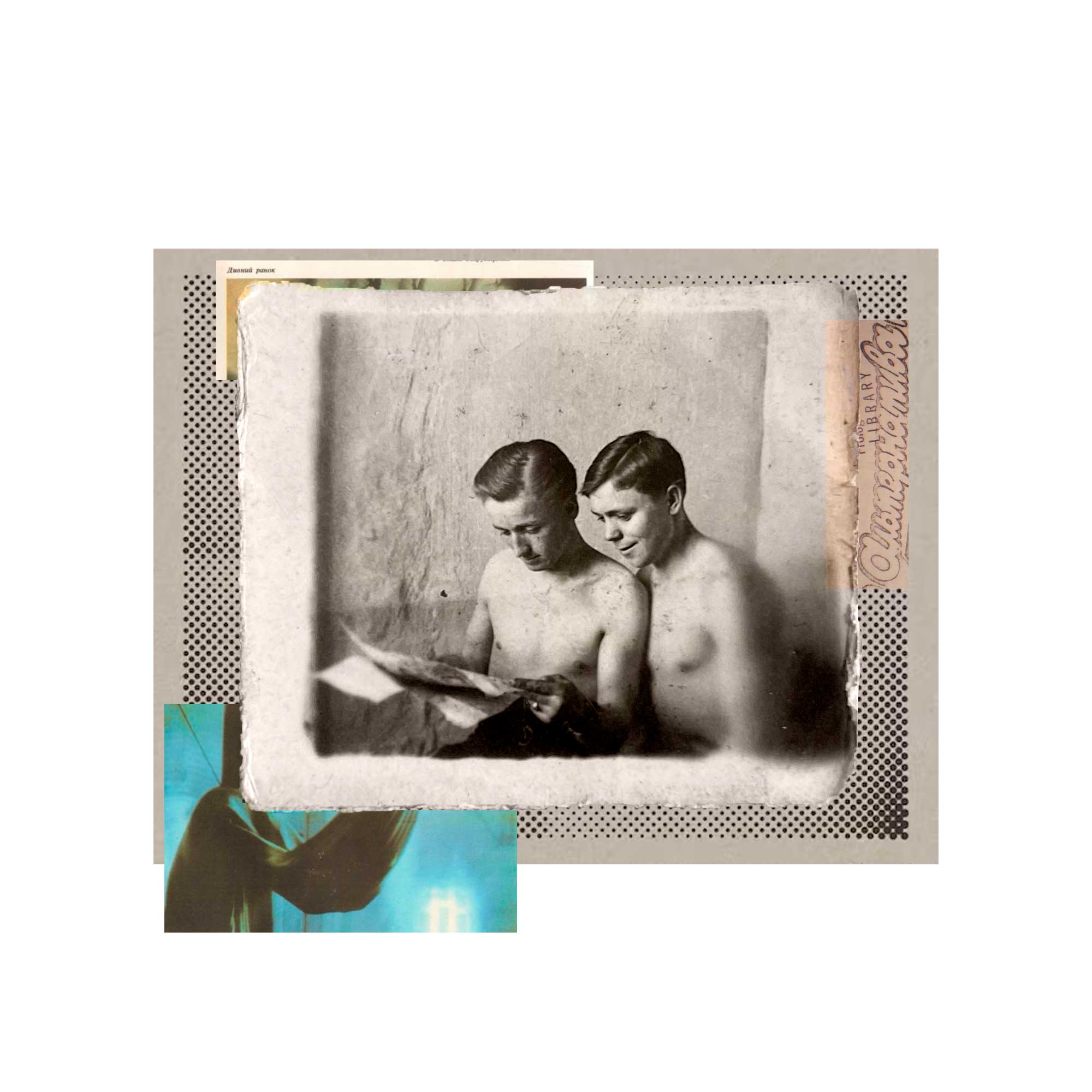

Workers of the sugar factory in the village of Dinklar. Mykola is the third from the right. Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo courtesy of Pavlo Bishko

The train station in Hildesheim, which was similar in architecture and size to the train station in Lviv, was also bombed. When the bomb hit there, the Germans were going to restore the railway station. The freight cars were destroyed or damaged by the bombing. Matsey recalls how the sugar factory workers and the director, Mr. Schaperman, went to clear the track, on which the wagons torn by explosions stood upright. In one of the cars, they stored food for the front. Mykola saw how canned cheese spilled out of it, but none of the Germans dared to take even one.

Near the sugar factory, there was a canteen where Ostarbeiters ate. The food was prepared by a woman (whose name Matsey does not remember) with her daughter Maria. Her mother called her tenderly — Marienchen. All the young workers of the factory liked the blond Maria, 16 years old, who lived in the house opposite the bread shop where the Ostarbeiters received bread. During one of the American bombings of Hildesheim, one bomb fell on Dinklar. Mykola and other Ostarbeiters, together with Maria and her mother, ran into the basement of the boiler room under the chimney. Hiding there, they baked potatoes on the fire. Matsey remembered the story of the baked potatoes. 45 years later, in the 1990s, this story helped him get compensation from Germany (more on that later).

Vacation

In 1943, Mykola received his first leave for one month. He went to the local market in Hildesheim to buy a suitcase.

– Bitte für mich einen Koffer (Please, a suitcase for me).

– Nein, das ist alles für Soldaten (No, suitcases are only for the military).

Mykola offered to pay more, but the seller refused because of the Ukrainian’s origin.

-

“I send you my picture as a souvenir. Matsey Nikolay from the Dinklar sugar factory”. The photo that Mykola sent to his parents. Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo courtesy of Pavlo Bishko

He got a loaf of bread for the journey, cut it into pieces, and smeared it with margarine. He went by train to Poland, and from there — to the Lviv region.

After the vacation, Mykola still returned to work in Germany — he was afraid of arrest and deportation to a concentration camp.

Siberia

On April 19, 1945, Allied troops entered Hildesheim. Matsey recalls how American soldiers treated him with chocolate and invited him to the United States. But Mykola was sent to the town of Parchim, which was under the control of the Red Army. Special services officers had a conversation with each Ostarbeiter. On May 12, the conscription commission at the field military commissariat sent Mykola to the 130th separate work battalion, after which he was sent to the war with Japan.

The battalion had to overcome the way through East Germany, Poland, and Belarus on foot. In addition to personal belongings, Matsey carried a suit purchased in Germany, which he wore only on Sundays. The battalion ate what they took with them in Germany. They usually spent the night in the open air. Once in the forest outside Warsaw Matsey lay down to sleep in a hole: his back was in the hole and his legs were on a hill. It was raining at night. Matsey was soaked, only his legs remained dry.

On September 2, Japan signed the surrender documents, thus ending World War II — Matsey’s battalion no longer had to go to Asia. Mykola was demobilized and sent to work at the Stalin Metallurgical Plant in Magnitogorsk. Through the window of a freight car, he first saw the mountains of the Urals, and beyond them — boundless and deserted spaces. Only on the third day of the train journey, he noticed people outside the window for the first time — a woman with five skeleton-like hungry children. Thus, after bourgeois Germany, he discovered Russia.

Magnitogorsk

Around the metallurgical plant in Magnitogorsk there were prison camps, where Matsey was settled, and then appointed as a gas welder. The plant was so large that Matsey compared it to the area of his native Starosambir district of Lviv region. At all five entrances of the plant, there were women armed with pistols. Lunch in the canteen was under the control of the guards, workers were fed according to coupons. When leaving, it was necessary to give your spoon, otherwise, you were not allowed to return to work.

-

Magnitogorsk, 1946. Photo courtesy of Pavlo Bishko

One of the workers went to order lunch and left the spoon on the table. When he returned, it was gone. Thus, he could neither eat lunch nor continue working.

German prisoners lived in dugouts around the plant. German soldiers asked Mykola about Germany. He told them about the intense bombing.

Matsey put his German suit, which he had carried through East Germany and Poland, in the storage room of the factory. Soon he saw only the broken glass of the cell. Matsey turned to the shop foreman, Mr. Nosak, a tall Ukrainian. He calmly replied to the theft of Mykola’s belongings: “Do not worry, we will soon receive “American gifts”. This was the name given to the belongings of killed prisoners of concentration camps, liberated by American troops.

Four years of hard work as an Ostarbeiter in Germany could not be compared to Soviet prison camp life. The factory was surrounded by tall residential buildings, and the area was polluted with feces due to the lack of toilets. One day Matsey witnessed a crime on the tram he usually took to work. One of the passengers noticed someone trying to pull another passenger’s wallet out of his pocket, so he publicly drew attention to it. When the tram was approaching the stop, the thief, holding a handkerchief with a wrapped razor blade, approached the witness of the theft and with the words “Here, blow your nose!” cut off his nose.

Soon after constant hunger and 40-degree frosts, young Matsey understood for the first time what freedom is.

-

“A souvenir from the Urals sent by Matsey M.”. Magnitogorsk, 1946. Mykola is on the left. Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo courtesy of Pavlo Bishko

Vacation with no return

A year of Matsey’s work in Magnitogorsk has passed. During this time, the plant’s employees received “American gifts”. Mykola received a jacket and pants, as well as a vacation permit. He stood in line for two days to the head of the personnel department to get the leave documents. By passenger train, through Moscow and Kyiv he finally arrived in Lviv region, from which he never returned to Siberia.

In Dobromyl he got a job as a gas welder at a local woodworking plant. Later he was arrested for “desertion”. The court decided not to return Matsey to Siberia, but left him to work at the factory in Dobromyl and ordered him to pay half of his salary to the state for 10 years.

“My four years during the war in Germany were better than one year in Siberia,” Matsey concluded.

Baked potatoes

In the early 2000s, the German government launched a compensation program for forced laborers of the Third Reich. At that time Matsey was already 80 years old. After learning about the possibility of financial compensation, Matsey’s family began to collect evidence of his work at the sugar factory. He lost almost all German certificates and documents in Magnitogorsk. There was no actual legal evidence that would prove the status of an Ostarbeiter.

Mykola’s family applied to the archives of Lviv, Kyiv, and Moscow. But they could not find any records there. The Dinklar archive replied that the sugar factory where Matsey worked no longer exists and that the records of the personnel department during the war were not preserved. The search for evidence reached a dead end.

For many years Matsey lived with pleasant memories of his youth during the war. He often told his children and grandchildren stories from Germany. One of them was about how during another American bombing raid on the vicinity of the sugar factory, he peaked potatoes under the chimney of the boiler room with Maria and the canteen workers.

Matsey’s family described this story in a letter to the Mayor of Dinklar. And also told about how Mykola repaired the bicycle to German policeman Hakke. A few weeks later Matsey received a reply that Maria had been found. She confirmed in writing that she was baking potatoes in the shelter with “Mykola from Ukraine”. The story about baked potatoes provided him with the status of an Ostarbeiter. Based on this evidence, Mykola received compensation in German marks.

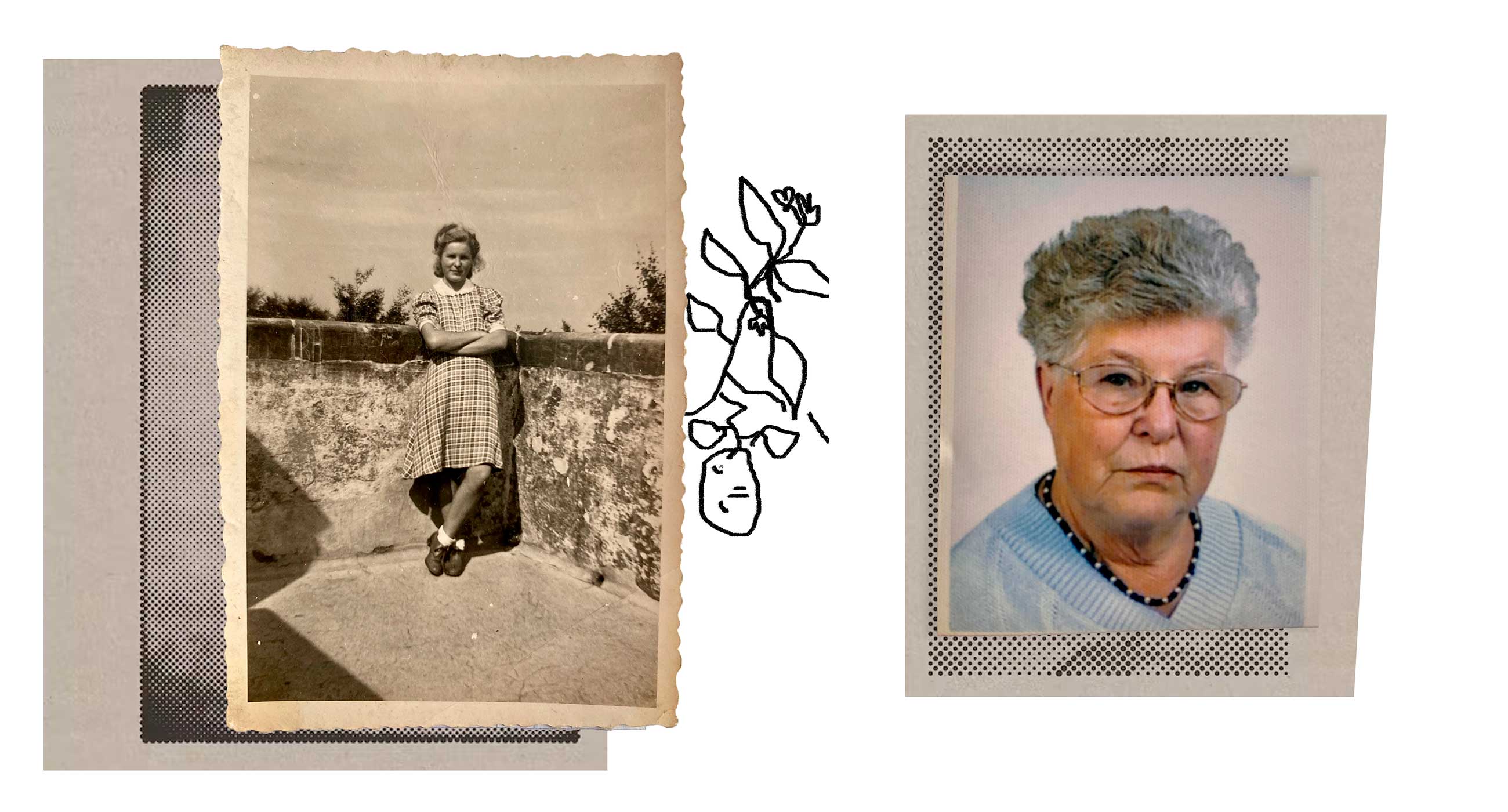

After some time Matsey received a personal letter from Maria. She told him about her family, her marriage to a Polish refugee from Szczecin, and the death of her son. For a good memory, Maria also sent two photos of herself — from 1945 and 2001.

Mykola divided some of the German marks among his children, and kept the rest for himself and his wife “to pay for a monument”.

-

Maria, daughter of a sugar factory canteen cook, 1945 and 2000. Collage: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona. Photo courtesy of Pavlo Bishko