At the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, a loud conflict occurred between a part of the Ukrainian film community and Ukrainian film director Serhiy Loznytsia: he was expelled from the Ukrainian Film Academy for “cosmopolitanism.” Since then, Loznytsia has released the documentary “The Natural History of Destruction” by W. G. Sebald, which was shown at Cannes in the spring of 2022, and “The Kyiv Trial” about the trial of the Nazis, presented at the Venice Film Festival in September of the same year.

Zaborona’s editor-in-chief Kateryna Sergatskova spoke with the filmmaker about the conflict with the Ukrainian film community, working with propagandist archival footage and how his film about the Russian occupation might look if he edited it from Russian television footage.

Greetings, Serhiy. While preparing for the interview, I thought about the Berlinale [film festival] that just passed, and I didn’t see your films there. Why?

Here you see the badge [points to the chest] is the Berlinale. I was there. I presented a film by [Lithuanian] Arunas Ževryūnos in the Coming of Age program — they did this kind of retrospective program of films from the 1960s, 70s, and 80s by different directors who other contemporary directors represent. [Gevrunos’ film] “The Beauty” (Gražuolė) is a stunning picture. Few people know it outside of Lithuania, but everyone in Lithuania knows it. It is a 1969 film about the tragedy of Lithuania but shot and made through the eyes of a child.

I haven’t made my new film yet. We started filming in Ukraine in August [2022], but so far, it’s one step at a time. I’m not in a hurry.

And what are you filming? Tell me.

I am interested in how people change in this tragic and terrible time. I shoot ordinary life, ordinary things. The war sees through it all. Occasionally, once a month, in different places, we prepare and then shoot. They were in Mykolaiv, Odesa, Poltava, Kharkiv, Kyiv.

A military hospital, for example, is where soldiers are rehabilitated after injuries. The school is how children study and, meanwhile, announced the bombing. RATS — a soldier marries a young, very young girl, and we understand that then he goes to the front. And, of course, farewell to those killed and those who gave their lives for the country.

It will be launched on the [Franco-German] channel ARTE in separate episodes, and there will also be a movie afterward.

Very interesting! Is it a character story or more of a chronicle?

Each episode has its heroes, but there is no through-and-through hero. I shoot the general state of things, but some themes run through this whole picture. Well, you’ll see it later.

Whose hands are you shooting with?

There are operators with whom I work, there are groups.

But you don’t go yourself?

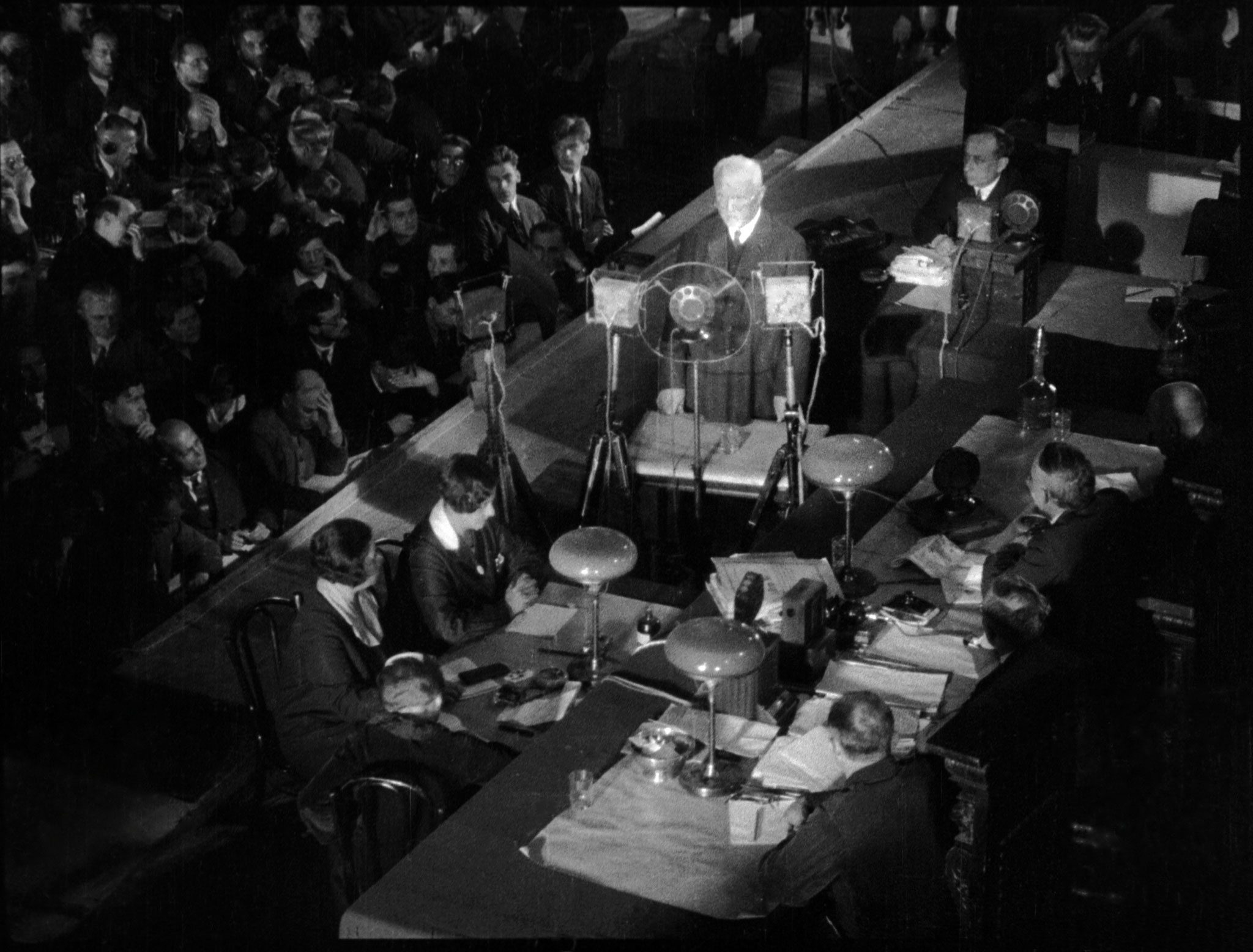

I myself finished two movies last year and presented them in Cannes and Venice. [One of them] is very important. Almost nothing was written about it in Ukraine, or all kinds of abominations were written. The film is called “Kyiv Process.” There are significant testimonies about crimes against citizens who lived in the territory of the former Soviet Union. And not only against Jews but also against Ukrainians and Russians. Moreover, there are a lot of testimonies from those regions where the war is currently going on. It all comes back. The crimes [then] are no different from those happening now — absolutely everything is repeated. Another thing is that the Russians are now acting as Nazis and aggressors.

This picture is very, very important. For example, I had no idea until a certain moment that there was a trial in Kyiv. I knew that this process ended with a public execution on January 28, 1946, but that it was filmed, not even historians knew. The idea [then] was to make a propaganda film, but the film was not made. All the material has been preserved in the Krasnohorsk Archive. It is a treasure. The truth of people’s life and suffering is revealed in the film — something that the authorities would not want to show.

I hope this film reaches Ukraine someday. It seems to me that returning this knowledge and material to the homeland is important.

Producer Maria Shustova, Serhiy Loznytsia, Ilya Khrzhanovskyi and Polish film editor Tomasz Wolski present the film “Kyiv Trial”, presented out of competition as part of the 79th Venice International Film Festival, on September 4, 2022. Photo: Marco BERTORELLO / AFP

Why is this film still not shown? Why are people so critical not only of your films but also of you personally?

You probably know the whole story.

What do you think about it?

What do I think about it? I think the detractors carried out a very clever operation. These two guys had reasons to get revenge on me for different things. One is [founder of the distribution and production film company Arthouse Trafik] Denys Ivanov, who initiated all this. He found this festival in Nantes [the canceled festival of Russian cinema “From Lviv to the Urals,” which was supposed to show films by Loznytsia], which I had no idea about, and checked it all on the Internet, whipped up a lather. Within one day, they quickly made a decision [to exclude Loznytsia from the Ukrainian Film Academy] without even addressing me or giving me the opportunity to talk. All this was done in the very Soviet traditions, with complete disrespect for one’s colleague.

Zaborona turned to Denys Ivanov to comment on the accusations against him.

Denis Ivanov. Photo: Wikimedia

“I found out from Facebook that there was a festival with that name, it was outrageous to me. People asked me why the film “Donbas” is being shown there [the company “Arthouse Traffic” is the Ukrainian distributor of this film]. I contacted the French distributor and asked to remove the film from the screening, to which I was told that the director was very happy to participate in this festival. After that, I raised a scandal. It seemed unethical to me that Serhiy Loznytsia takes part in such a festival — let me remind you, it was in March of last year [at the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine].”

Denys Ivanov made a movie, “Donbas,” with me. I didn’t let him “save” for the producer’s benefit — I made sure that all the money allocated for the film went to film production, so we paid Ukrainian actors the same as the rest (we had actors from Russia and Germany).

This discussion reached the head producer [Heino Deckert], to whom I told (when I had the opportunity) that I would not do the picture otherwise because I would feel highly uncomfortable. I don’t understand why we should pay Ukrainian actors less. Denis Ivanov explained to me that we have such prices. And I don’t care what your prices are. We have a German picture. I made this picture, and I respect the actors endlessly. I believe that everyone should receive the same amount if we have money in the budget. It is the first.

There was a whole series of clashes in which I remained the winner because my argument is very simple: then I don’t work on the picture, we close the project. I constantly had to fight. For example, under conditions for actors in mass scenes, of which we had many.

On the first day, when there were primarily older adults, there were no tents, benches, or tables. They just stood in the corner — such a production. And then there were many different clashes.

I’m just sure that [on the part of Denys Ivanov] it was revenge. He is a very rude person.

In a conversation with Zaborona, Denys Ivanov said that the situation described by Loznitsa during the film “Donbas,” filmed in 2018, did not correspond to reality. Still, he did not deny that there were conflicts or disputes, “as it always happens in the film production process,” but noted that they “saved a relationship” with the director after filming. Ivanov also said that filming “Donbas” in no way relates to the conflict that occurred during the full-scale invasion. Denys Ivanov said the open antagonism began when Serhiy Loznytsia started cooperating with the Babyn Yar Memorial Center. “It was a worldview conflict,” Ivanov explained.

A frame from the film “Donbas”. Photo: PYRAMIDE FILMS

Denis Ivanov is one person. And who is the second?

Pylyp Illienko [film producer, former chairman of State Cinema, chairman of the board of the Ukrainian Film Academy from 2020 to 2022].

I can tell you about him separately. In 2018, there was an attempt to allow only films in the Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar languages to be accepted for selection by the Oscar committee (I was a member of it). That is, if you make an utterly Ukrainian film in Yiddish, or Polish, or, God forbid, in Russian, or in Romanian or Hungarian (we have Transcarpathia speaking Hungarian), then this Ukrainian film will not be allowed to be selected by the Oscar committee.

There was a big discussion between the members of the Oscar committee. Of course, I was outraged by this — it is an act of repression on an equal footing in relation to my colleagues. In 2018, this idea did not pass: after all, the majority did not support it. The following year, [members of the Ukrainian Oscar committee] were rotated, and new people appeared there.

And, just like last year, a week before the meeting, there was news that we would accept this norm. No discussion during the year — very Soviet methods. If you do not agree [to accept this norm], no Ukrainian film will be presented at the 2019 Oscars. The storm and discussion started again. As a result, they did get this norm. Myroslav Slaboshpytskyi and I left the Oscar committee as long as this norm exists.

After that — I assume there would be no scandals — they agreed to submit one film from Ukraine to the committee — “Home” [director Nariman Aliyev]. It was filmed in Ukrainian and Crimean Tatar languages, and it’s wonderful. No need to sit down: this is the only movie submitted automatically. It is diplomacy in Ukrainian.

In 2019 [the presidential election], Zelensky won. The following year, other members of the committee and I received a letter: “Dear friends, we have changed the regulations again. We are withdrawing this norm and abandoning it. Now, any films made in any language are worthy of submission to the Oscars. What do you think about that?” Everyone wrote: “We agree, great.” Those who remained silent or fought, with foam in the mouth defending the right to repress all other languages, said: “We agree. Fine”.

It’s one thing to discuss, but for the first time, I see it turn into a serious conflict, which entails specific actions — such as expulsion from the film academy. It is a serious story, in my opinion.

These initiators could have entirely personal reasons. But what is impressive is what concerns the procedure itself [exclusion from the film academy].

Many [foreign] members of academies asked me: “How is it anyway? Did you have any discussion? Was the academy gathering?” No one discussed anything, and it was done on Facebook: No one, of course, approached me to have some discussion (Zoom, not Zoom — whatever) where everyone would express their opinion. It was deflated, like in the Soviet Union.

Everyone [members of other film academies] shrugged their shoulders: how possible? The Lithuanian Academy, for example, if they have such a conflict, meets, discusses, and listens to the opinions of the parties. Where to hurry?

Pylyp Illienko. Photo: Wikimedia

Zaborona asked Pylyp Illienko to comment on the director’s statement.

“I have no personal complaints against [Serhiy Loznytsia] as a person. I had a critical attitude towards his position on the abolition of Russian culture, which I publicly expressed,” he explained.

Regarding the procedure for expulsion from the Ukrainian Film Academy, Pylyp Illienko said that the meeting was not held because the war was going on: “There was a discussion with the members of the board and the supervisory board online, and I appealed [about the expulsion] to them publicly, this was done according to the statute of the Film Academy.” Regarding the organization of the discussion with Loznytsia before his expulsion, Illienko said that “he [Loznytsia] expressed his position publicly, I also expressed my position publicly. He was outside Ukraine then, and I was in Ukraine — how could I communicate with him, except in the format of a public discussion?”

According to Denis Ivanov, a member of the board of the Ukrainian Film Academy, Serhiy Loznytsia was not approached because it was necessary to resolve the issue of his exclusion quickly: “It was March 2022, and there were more important things.” He said the exclusion’s purpose was for the film director to “stop speaking as if for all Ukrainian directors.”

As for me, I have received a significant number of letters from very different people: “What’s the nonsense?” Everyone has seen my films, and everyone has read my interviews. Everyone knows my opinion. On February 26, I posted what I think about this war on Facebook, and you can read everything. Then many different and very famous publications fell on me, and I gave interviews. I considered it my duty to give an interview; I explained that this war has been going on for 8 years, that it will be a very long time, and that it is a disaster. Of course, I defended the position of Ukraine.

The only thing I can’t agree with, which is delusional, is the repression of one culture or another because this or that government behaves this way and pursues such an aggressive policy towards anything. It is generally a precedent in world history. Yes, of course, there were excesses during the First and Second World Wars. But why repeat the nonsense that certain governments have done for propaganda purposes? And in general, it is necessary to understand when and where such a concept as culture war appeared. Who used it, for what goals, what is it generally, and does it have any basis?

As a person who creates films from the archives of propaganda filming, you probably have an answer to this question. Or not?

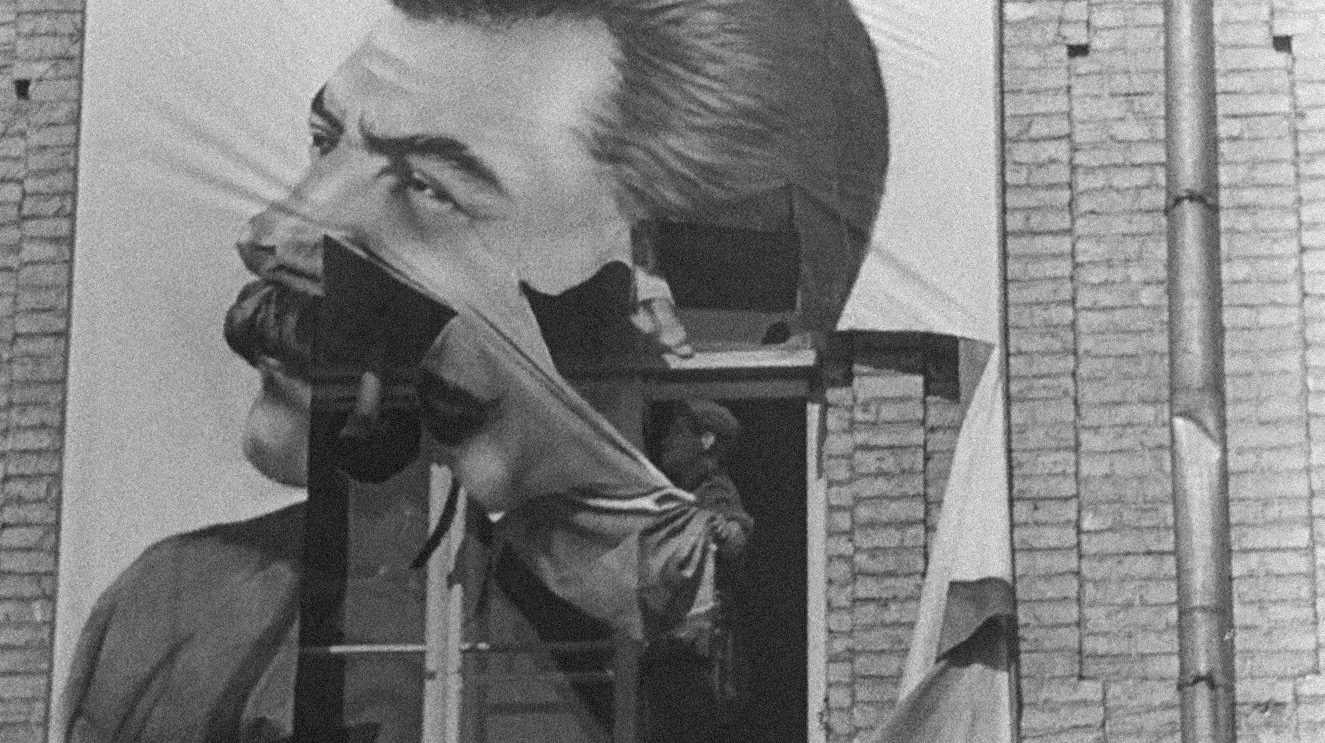

Propaganda shooting… It is a very complex concept. For example, I made a film about Stalin’s funeral. Well, a camera is filming people moving towards the colonnaded hall of the House of Unions. Is this a propaganda shoot or not? It’s just a fact: some stand, some cry, and they carry wreaths. You then make a film with a purpose, and it becomes propaganda.

Or for example, the film “Putin” was made by Vitaly Manskyi (a great director). There is a scene where Putin comes to his teacher – this scene is fictional. There was no such idea in reality — to go to the teacher. This scene moved lots of people. It is propaganda, you know?

In principle, when you start working with the material, you filter out some footage as propaganda. For example, I had material in the “Blockade of Leningrad”: winter, snowstorms, a man walks past the bars of the Winter Garden, and falls — shockingly. Then the next shot takes two, the same thing. It was in life, but why shoot it as a feature film with actors? This shot is hard for me to take.

But there are such frames of symbolic value. For example, some older women drag a coffin along the Neva [river in St. Petersburg], and we see the Peter and Paul Fortress, it’s practically a painting by [Russian painter Vasyl] Perov. They drag the coffin diagonally, and the frame is constructed — certainly, it was shot on purpose. But this is a frame that has a generalizing value. I used it.

It’s not even crucial whether someone filmed it on purpose or not — it’s important what your opinion is. I made an anti-Soviet picture from these frames. My idea was to take the materials they used to confuse everyone and expose this oppressive propaganda machine’s essence and crimes against childhood and children. They formed and transformed the consciousness of the growing generation — this is the most terrible thing. I made a film about this using such footage. So it’s not such a simple question.

The film “Babyn Yar. “Context” you also made from propaganda footage, but already Nazi footage. It begins with footage of Ukrainians saluting Hitler, marching under Nazi flags with flowers, dancing, and singing. Of course, it’s hard to argue with historical facts caught on camera — that’s what happened in real life. But why did Ukrainians welcome Hitler? Maybe they didn’t want to do it, but they did it because, for example, they understood the consequences.

For example, I am thinking of Russian propaganda footage in the Kherson region, which was under Russian occupation for 9 months. There were shots where pensioners stand in line for a humanitarian worker and happily take her away, as in your film “Babyn Yar. Context” people stand in line for newspapers. And then, after de-occupation, we learn how the Russians tortured people. We see the graves of those who the Russians killed for resisting. And if a film chronicling Russian propaganda were made today, we probably wouldn’t see the actual aggressor behind it either.

The main criticism that sounds in your direction, and I somewhat agree with it, is that the aggressor himself is not visible behind the propaganda footage. Did you think it could be perceived that way because of the lack of real footage, an explanation of what was happening at that moment?

It is impossible to claim its incompleteness to any film at all if it is not an encyclopedia. No movie can exhaust all the stories that explain this or that behavior of people within 2 hours. And in general, it is not the task of the film to explain. The task of the film is to raise questions, to encourage the viewer to look for answers, to impress, but not to explain what happened there. Please search. I’m trying to engage the viewer.

If you are interested, you will go further and start reading why, for example, the arrival of [one of the Nazi leaders] Hans Frank on August 1, 1941, in Lviv, was arranged in such a way. In Kyiv, this was not the case. Why was a [Jewish] pogrom possible in Lviv (there were five of them), but in Kyiv, no matter how hard they tried, there was no pogrom? That is, it was not possible to provoke. These are very interesting questions.

But to answer them, I must devote the entire film to it. It is difficult for me, for example, to introduce an explanation or a voice-over into the movie because I will destroy the very manner of the story, the conventionality of the world of the film.

If you go to Wikipedia or somewhere else, you will find out that in 1939 and even 1941, 60% of Poles, 25% of Jews, and 11-12% of Ukrainians lived in Lviv. Do you understand? As you say, those who go [to greet Hitler] are mostly Ukrainians. But what do we mean when we say “Ukrainians”? Citizens of former Poland occupied by the Soviet Union (to be correct). When Lviv was liberated/occupied (everything depends on the point of view), it was done by the Kraiova Army. There is a shot in the film where red and white flags are hung on a building in Lviv — these are Polish flags. There was hope that Stalin would return Lviv with this part of Galicia to Poland. It is the story.

And if you look at the scene of the pogrom, the people participating were civilians, wearing hats and holding spikes; they had bandages. It was the police, mainly [represented] by members of the OUN. It’s true, and we can’t get away from it. Of course, the pogroms were provoked by the [Wehrmacht counter-intelligence agency] Abwehr. Together with the SS, they did this specifically to promote the idea of mass extermination of Jews. They wanted to show the chaos that would ensue if they did not control the situation. They have long cooperated (some excellent historians have already researched all these materials) with the OUN(b) and OUN(m) organizations. Each had a different attitude to this cooperation, and different German army units cooperated with different teams. It is also a fascinating story.

It was promised to create an independent state under the German protectorate. And on June 30, the creation of this state was announced ahead of any agreements. You know the story. Stetsko headed this state, but the Germans immediately closed this whole story. Stetsko was arrested and sent to Sachsenhausen; Bandera was placed there. And gradually, they pumped the brakes so as not to make noise. Ukrainian nationalists were deceived by both the Abwehr and the SS. They were simply used. And then, when Hans Frank announced on August 1 that this part of Galicia would be under the protectorate of the Polish Governorate, immediately some of the police officers and those who belonged to the OUN went to the forests and began to fight on two fronts: against the Germans and the Soviets. It is a historical truth.

You can read it in several books, but it cannot be shown in a movie. The film is not dedicated to this at all. It is about the extermination of the Jews in this territory. The film is dedicated to this.

So when you watch a movie and say, “That’s how you showed it,” well, I’m sorry, I didn’t show it, I didn’t shoot it, I wasn’t standing there.

Кадр з фільму «Бабин Яр. Контекст». Фото: IMDB

Frames from the film “Babyn Yar. Context”. Photo: ATOMS & VOID

But you made a selection.

Of course, but this is a critical moment — the arrival of Hans Frank in Lviv. It is a very important point. I could [make] a whole film about the relationship of the German authorities with the civilian population and so on. It is a separate topic, and you can watch it.

You say that this is material filmed for propaganda. No, not all. There is some unique footage that I found that no one knew existed. These are, for example, footage of the first explosions in Kyiv, taken by a German officer. There are many such personnel who were not included in any propaganda at all. These were cuts that were not included in the editing. They were in different archives.

Throughout the [existence of] the Soviet Union, the state controlled any filming. You could shoot with a personal camera in the Soviet Union only starting from the 1960s. Before that, all images were under state control.

Someone says: “This film was financed by such and such a country.” But [Ukrainian director Oleksandr] Dovzhenko made a film financed by the Stalinist regime, which has the blood of millions, tens of millions of people on its hands. Are there problems with Dovzhenko and his film, for example? Are there any complaints against [Ukrainian director] Dzyga Vertov? It is a very strange narrative.

What exactly are you talking about?

For example, there was a film by a Chechen girl, a student of [Russian director Oleksandr] Sokurov at the Berlin festival, or [Russian director] Natalia Meshchaninova at the Rotterdam festival. It is not a film that glorifies Putin’s regime or treats this state in a complimentary way — it is always a protest film.

There is a wave of cancellations of these films. But if we cancel these films, let’s go back to our history and see who made the film [Olexander Dovzhenko] “Earth.” On whose money? At what time? It was 1930, just collectivization. It’s a fantastic movie, but I’m just going with the rhetoric. And what were the next films? “Schors” is a stunning film, “Michurin” is a stunning film, and “Battle for Right Bank Ukraine” is a stunning film. All this was done, in particular, with state money, and at the same time, there is such a dissonance. I question the validity of this rhetoric.

During the times of the Soviet Union, there was an iron curtain, that is, Soviet culture was naturally boycotted in the West.

But it is not so. Pasternak was the first to be published in the West. Solzhenitsyn was published in the West.

They were Soviet dissidents.

Tell me, what kind of dissident was Emil Lotianu, who shot the picture “A Hunting Accident”? This 1978 picture opened the Cannes Film Festival. Was he a dissident? No. There were special relations, but the West had nothing to do with it.

We are now talking about us, about people. And our relationship. First, the media was not so widespread, and we knew nothing about it. Secondly, no one would have had the idea of such a revision — even if they had found out, they would have said “horror.” Now the crimes of the Russian authorities [are committed] by the hands of their fellow citizens, you understand. And these crimes do not become smaller because of this. But I’m talking about our attitude and this idea that suddenly arose — to persecute the culture for it. It, I think, is delusional.

Criminals must be prosecuted. There will be international justice in The Hague, and I would like all the criminals to be punished so that it somehow prejudices crimes in the future. But what does culture have to do with it? I’m only against it.

It is also the attitude towards fellow citizens. Even if 15–20% of the population speak this [Russian] language, it is their culture. Why start a war, including against its own people? All this does not seem very reasonable to me. And in this sense, I cannot love my homeland blindfolded. It does not lead to defeating the enemy. It does not help us; on the contrary, it creates completely different conflicts for those who could become our allies. Why pursue them?

I have a very simple example — the film “The Process” by [Russian documentarian] Askold Kurov about the case of [filmmaker, former Kremlin prisoner Oleg] Sentsov. After the Ukrainian Film Academy and Derzhkino appealed to block Russian films, this film also suffered. It was supposed to be released but was removed from all festivals. Where is the logic here? You beat your friends and allies.

A frame from the movie “Process”. Photo: IMDB

I remember when I was in Berlin at the showing of this movie, where representatives of the German authorities and Ukrainian representatives gathered. Everyone was proud — from the ambassador to the head of State Cinema. And now no one intervened, did not say: “Guys, let’s not engage in madness.” In my opinion, this is treason. Moreover, Askold Kurov took many risks when he made this picture.

It is a good example, but I know that directors like Askold Kurov understand their works’ inappropriateness [could be present at festivals and draw attention to Russian directors at a time when Russia is bombing Ukraine].

I know many [Russian] directors who have always been against this regime — they left the country. They do not have the opportunity to present their picture: festivals hardly accept such. There is no way to get any funding. Put yourself in their shoes. You’ve always been against it, done something important, and were instantly thrown out. They say: “Understand, this is the situation; this is how it should be.” Why is it necessary? I do not understand. Askold Kurov is a very intelligent and delicate person.

Therefore, he understands why this happens.

He understands, but I don’t. For me, this is humiliation and betrayal. That’s why I said what I said. And this was the reason for people who had additional different claims against me to quickly and swiftly, without any discussion, turn the campaign around. They accused me of being a cosmopolitan. Well, that’s idiocy.

You say to yourself that you are a cosmopolitan, right?

And what is wrong with cosmopolitanism, tell me? A cosmopolitan is literally a man of the world. World citizen. Puts the interests of humanity above the interests of a single nation or state. Do you have anything against it? We are the people of the Earth. Socrates was a cosmopolitan, and he expressed this idea. Cosmopolitans were [Russian writer Lev] Tolstoy, [German philosopher Immanuel] Kant, and so on — many people who believed that we needed to move toward uniting the world into a single civilization. Locking everyone in their own space is very strange and dangerous. It is necessary to open up, and it is necessary to exchange.

I usually have 10 languages on the set when I shoot films. I love it when everyone speaks different languages. I have a cameraman from Romania, a line producer from Latvia, an editor from Lithuania, and lighting people from Germany. What’s wrong with that? The producer is from France, and my assistant is Polish.

It is the friendship of people; this idea of the European Union is wonderful. If you all want the European Union, accept the cosmopolitanism idea. In the Soviet tradition, the word “cosmopolitan” became an insult. First, the Nazis, and then Stalin repeated them. He called the Jews stateless cosmopolitans; this euphemism still works here. It doesn’t concern me, and I’m not Jewish, but it worked out that way.

If we are talking about art, it would be great to enrich the knowledge and achievements of world art and culture of the heads of those who will move and change it in Ukraine. We already, in principle, use everything that previous generations of cinematographers have worked on if we talk about cinema.

You call yourself a Ukrainian director, right?

What does “I call” mean?

Do you exist as a Ukrainian director?

Yes, I have Ukrainian citizenship. I am from Kyiv.

I saw somewhere that you are called a Ukrainian, Belarusian, and Russian director at the same time.

Beautiful and wonderful. But there was a time when there was some kind of victory, and each country tried to attribute it to itself – this is natural.

I was just born in Belarus. I lived there for 6 months because my mother’s parents happened to be there. My grandfather is from Odesa, and my grandmother is from Armavir, a Cossack settlement south of the former Russian Empire.

If you do a DNA test, you will find mixed blood. It’s also a very interesting experience, this idea of cosmopolitanism.

It turns out, on the one hand, my closest relatives are in Sweden and Scotland. On the other hand, (surname and other relatives) are the Balkans, they are Serbs who fled from the Turks. The third relatives are Sarmatians and Scythians, the south of Ukraine they once mastered. And Balts, of course, I have a lot of Baltic blood. And then you ask me: from which tribe am I?

When we talk about belonging to one or another state, this idea appeared in general, maybe 4 centuries ago. Previously, the question was asked: “What is your faith?” The second question was: “Who do you pay taxes to? What king or prince protects you?” States as entities to swear allegiance to in subsequent generations appeared 3-4 centuries ago. This idea is temporary. After some time, I am sure, these states will dissolve as such.

The European Union is such a step towards the dissolution of borders, mutual penetration, and the opportunity to work where it is better for you because the economy and development need it. These territories will move in that direction — I hope the war will not push us too far back.

For example, I was flying to Switzerland, and I managed not to show my passport either there or back. I didn’t have any things, and I was completely calm. It is the feeling that you are in one country – the European Union. It is exactly how Ukraine wants to live — to feel part of a united Europe and not be locked in its own space. Therefore, cosmopolitanism is an essential idea.

You and I started talking about the films you are currently shooting in Ukraine, but you are not physically present there. Do I understand correctly?

No, I haven’t been there yet. After I presented the film [The Kyiv Trial] in Venice, I spent four months working on a play based on Jonathan Littell’s book, The Beggars. The premiere took place in December. I could not devote this time to anything [else] at all.

I haven’t gone to Ukraine yet, because I have a lot of things to do here. And it is still not clear how to get there.

A frame from the film “Kyiv Trial”. Photo: ATOMS & VOID

Are you worried that you might be drafted into the army?

No, I’m not worried. It is the most useless act — I will not benefit except as a part of propaganda.

Then you will not be released.

I don’t know what the situation is. I am not yet 60 years old. But that’s not even the point. These guys [Denis Ivanov and Pylyp Illenko] did such a stupid thing — they created such an image for me in the country that it is complicated to continue. The last thing I read, someone wrote about the films presented at the Oscars from Ukraine. And also this comment about me: this film was presented until the director was disgraced as an agent of Russian influence. It is an absolute lie. And this lie appears in the media in passing, daily. Sure, you can sue, but why all this now? I do not know for what reasons and on what basis these unscrupulous people can spread [such information].

That is, you are worried about your safety, so why are you not going to Ukraine?

I just don’t know how to be in such a situation. It is not only a matter of my safety but also of all those who will be with me.

Actually, my question is more about movies. You act as a director and give a specific framework for those who shoot for you. How do you build trust with those who shoot this material for you? Aren’t you afraid you may not get all the information or an incomplete picture of what is happening? After all, you are not there. Personally, you do not have a connection on the territory with people who are experiencing the war right now.

First of all, I have… The people who are going through the war now, there is a huge number of them here in Europe. And in Berlin, Vilnius, and Warsaw. You just go and hear — mainly, by the way, the Russian language. Then, when you ask, they tell you: “I’m from Luhansk,” “I’m from Donetsk,” “from Mariupol,” “from Kharkiv,” and so on.

Secondly, there are certain shooting methods. I shoot with long shots. It is the kind of camera that watches and is very difficult to fool.

Thirdly, I have already made about a dozen documentaries from the chronicle. And what is being filmed now is a chronicle. Of course, I sit virtually in something that gives an idea of Ukraine around the clock. I’m there.

This war… It’s a horror that it started. It was clear that it would begin. In 2009, I asked the guys with whom we shot the film “My Happiness” what they would do if Russia attacked. They laughed, perceived it as some kind of nonsense. But it was already clear.

War closes all other possibilities. There remains only the opportunity to fight and nothing else. It is not clear what future this war has. It will last a long time, I can tell you. It just won’t end like that. That’s why I’m not in a hurry either with the film or the filming. Gradually, slowly, this experience accumulates because it requires awareness.

It is unclear what a film about war is, but the movie’s theme is essential. And the most important topic is the price that the country, citizens of the country, pay for their freedom and independence. It is important to understand that freedom and independence are defended only in this way. The price is the highest.

How would you describe this price?

It’s life. People pay with their lives not to be in a totalitarian state and not to return to the Soviet Union. It seems that the most important thing now is to work on what kind of state will be next. It would also be very strange to return to what was before the war.

Have you thought about how you could personally contribute?

I have a profession, I have my opinion and express it. There should be an open, multicultural, multinational state. And then it’s a serious conversation.

If you take the Constitution of Ukraine, you will find three concepts on the very first page, and it is unclear which concept means what. The first concept is the people, the second is the Ukrainian people, and the third is the Ukrainian nation. Implied? It seems to me that starting with the fundamental law is necessary. It should then determine how we see the country.

Different models exist around: there is Germany, there is Norway, there is America, and there is Great Britain. The Constitution states that Ukraine is a social state. There is a welfare state in Germany where you pay tax, which is distributed among others. Everyone should get help if they can’t find themselves — society helps them. Ukraine is not a welfare state. What support do people who have lost their apartments and escaped this hell receive?

As a director, you probably can’t change that. Any ideas?

We are talking to you — maybe someone will hear it. My parents have left [from Ukraine], and I am trying to somehow arrange remotely for them the possibility of receiving a pension in a bank account. It would seem like a simple procedure, but it is impossible to arrange.

I do not understand: during the year of the war, it is not possible to find an opportunity for such people who left? They cannot come, they are over 80 years old. At the same time, “Diia” exists, but it is absolutely impossible to do something. It’s small, but it tells about the attitude toward people.

Will you publish it? After a long period, this is the first interview.

I know.

You ask how this [expulsion from the Ukrainian Film Academy and the accompanying scandal] affected me. On the one hand, not at all — I only had more questions. Everyone is surprised — what kind of delusion? Everyone knows my films very well and does not understand what happened to this academy. I have to explain that this is not the opinion of the Ukrainian authorities. As you know, Volodymyr Zelenskyi spoke on this matter, did not support this decision, and said it was stupid.

But occasionally, some festivals receive retroactively unfriendly letters demanding, for example, not to show the film “Donbas” or “Maidan.” This is absurd.

And they don’t show?

They show, of course. These are films that have been released once again. A significant part of the rental income went to help Ukraine. And then some person appears who represents the state at the “Days of Ukrainian Cinema” at the Cinematheque (a respectable place in Paris) and says: I am unhappy that this film was chosen to open or to be shown at this forum of Ukrainian cinema. After that, the representative of the embassy [of Ukraine in France] is forced to say that this is a private opinion, and both the ambassador [of Ukraine in France] and the president of [Ukraine] like this person’s films.

It hangs like a black cloud. Anyway, I will continue to make films. The whole world continues to consider me a Ukrainian director. I will participate in several almanacs as a representative of Ukraine. Other very famous directors will be there. It [the situation around Loznytsia in Ukraine] is just puzzling. I think it’s stupid. I believe that eventually, everything will settle down somehow.

Even this fact is interesting: in various programs of the Cannes Film Festival over 30 years, there were 13 independent films from Ukraine — 8 of them were mine.

I think no one doubts your talent.

What do they doubt? My decency?

You said it was unclear why there was no discussion about your exclusion. I think that’s exactly what you’re missing.

In this case, it is too late, it is already done. The event happened.

It’s never too late.

We need to restore the status quo and then start the discussion. I am not rushing to the Academy, I do not need it at all, but the discussion will remove many questions because I don’t know how to continue to exist with this. We have reached a dead end.

Still, no world will stop performing [works by Russian composers Dmitri] Shostakovich and [Peter] Tchaikovsky, playing [plays by Russian playwright Anton] Chekhov, showing [films by Russian directors Andrei] Tarkovsky and [Andrii] Zvyagintsev, [Alexander] Sokurov. It will never happen; it’s ridiculous. They have nothing to do with this war at all.

As a scientist, it seems to me that this is a false reference from which false conclusions have been drawn. The one who insists on error will simply come to an absolute dead end. It is better to focus not on clearing the territory but on creating something. Create something that everyone will reach for. Now all the gates are open to creators from Ukraine. Please create. Let people get excited; let millions watch movies. Focus on this and do — prove your ability, talent, and genius in art (in what you do).