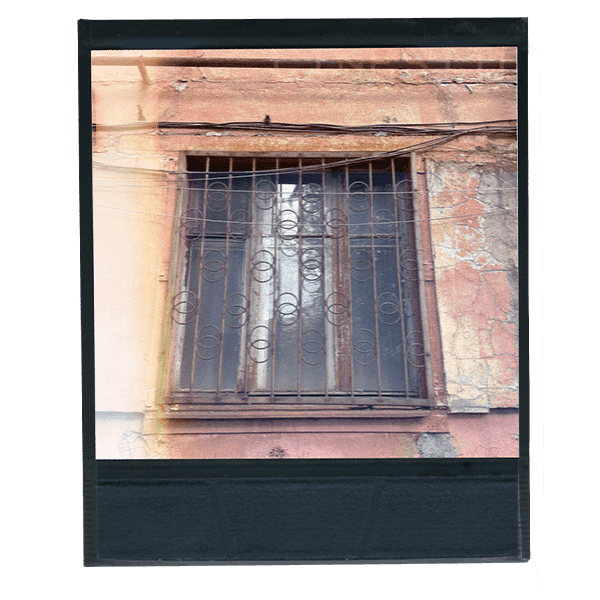

A thing that reminds me that there is no need to recall childhood

I am standing under the window of my childhood home. For the first time since the big war, I am walking on the pavement of my hometown, covered with tobacco-colored dust. I came to Zaporizhzhia for exactly two things: to photograph this window and to go through the belongings of my dead for this project.

As I wander around the courtyard of this pink house (unsurprisingly, it hasn’t changed at all and has never even been painted), the fifth siren wails. The last time I stood here was in the second month of the Covid-19 pandemic, and before that, perhaps, 20 years ago. Our apartment (can it still be called ours?) is located on the first floor. In 2001, when we moved out, it was bought by a woman who died of cancer within a year — her relatives either didn’t know about the apartment, didn’t keep in touch with her, or lived in some distant city; the apartment remained an orphan.

That covid April, I grabbed the window bars for the first time, pulling myself up to the dusty glass. There are things that punch you in the gut harder than a fist: the same white plastic table with an umbrella hole, like in cheap diners of Berdiansk, blue and white tiles, and a two-burner stove — my childhood behind millimeters of glass, like an exhibit in a showcase.

In his novel “Time Shelter”, Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov offers a piece of advice: never return to your childhood home. I don’t know about you, but I agree.