The Dream of White Socks.

Alina Smutko in “Zero Censorship”

Every two weeks Zaborona publishes “Zero Censorship,” a series that highlights the work of a photographer, artist, or collective that either isn’t in tune with popular culture, or has been censored in the news and on social media. In this issue we’re publishing a collection of photos by photographer Alina Smutko.

The Dream of White Socks.

Alina Smutko in “Zero Censorship”

Every two weeks Zaborona publishes “Zero Censorship,” a series that highlights the work of a photographer, artist, or collective that either isn’t in tune with popular culture, or has been censored in the news and on social media. In this issue we’re publishing a collection of photos by photographer Alina Smutko.

Four out of every thousand births in Ukraine are stillbirths. However, says Alina Smutko, that figure isn’t exact, because in post-Soviet countries, it’s still common to “clean up” official statistics:

“A baby who dies during childbirth might be called a ‘miscarriage,’ while a baby less than a week old might be a ‘stillbirth.’ So nobody knows how many pregnancies don’t lead to ‘motherhood,’ said Smutko. “All because, for the first three months of pregnancy, women are alone in their new status: state sources refuse to include them in statistics. Women who’ve lost a child to miscarriage or stillbirth, or even an early abortion, are met with apathy in society. Family and friends don’t discuss the loss of an unborn child with mothers, opting to pretend that nothing happened. Women are also often faced with callous and incompetent medical personnel. Every woman who’s been in this situation has heard something along the lines of “don’t worry, you’ll have another one.”

Alina Smutko’s collection “The dream of white socks” tells the story of six Ukrainian women who have experienced perinatal loss. Each of them is different: one lost a child thirty years ago, one of them quite recently; one of them risked having another child, while others stopped trying for natural motherhood. These women have one thing in common: a desire to help other mothers survive their loss.

Four out of every thousand births in Ukraine are stillbirths. However, says Alina Smutko, that figure isn’t exact, because in post-Soviet countries, it’s still common to “clean up” official statistics:

“A baby who dies during childbirth might be called a ‘miscarriage,’ while a baby less than a week old might be a ‘stillbirth.’ So nobody knows how many pregnancies don’t lead to ‘motherhood,’ said Smutko. “All because, for the first three months of pregnancy, women are alone in their new status: state sources refuse to include them in statistics. Women who’ve lost a child to miscarriage or stillbirth, or even an early abortion, are met with apathy in society. Family and friends don’t discuss the loss of an unborn child with mothers, opting to pretend that nothing happened. Women are also often faced with callous and incompetent medical personnel. Every woman who’s been in this situation has heard something along the lines of “don’t worry, you’ll have another one.”

Alina Smutko’s collection “The dream of white socks” tells the story of six Ukrainian women who have experienced perinatal loss. Each of them is different: one lost a child thirty years ago, one of them quite recently; one of them risked having another child, while others stopped trying for natural motherhood. These women have one thing in common: a desire to help other mothers survive their loss.

Baby Aleksey’s onesie. The boy was born prematurely at 28 weeks and lived a little over a month. Yulia saved a few of his things in memory of him.

Yulia, 36 years old, lost her baby at 48 weeks

“Some people say, ‘I don’t want to ask because I don’t want to remind you.’ Remind me? Seriously? I’m thinking about it 24 hours a day. There’s not a moment when I don’t remember my baby. Even after having two healthy children, I still remember Lyosha every day.”

Baby Yegor’s hat and socks. He was born prematurely at 24 weeks and lived eight days. His mom and dad called him a “little Smurf” because of this blue hat, which they put on him when he was in the ICU. Olga keeps his things in memory of him.

Olga, 33 years old, lost her baby at 24 weeks

“The doctors asked whether we wanted to take the body. Of course, of course we did! They don’t even make such small coffins. They put him in a child’s one, but it swallowed him up, he was so small. I know that in the States you can bury a nine- or ten-week-old, but here he’s not even considered a person before 22 weeks. And they won’t save him. I understand that from a professional perspective it’s probably not possible, but to call a dead child ‘medical waste’ — it’s awful.”

Baby Artyom’s ID tag, which Katya kept in memory of her son. He died soon after being born because of an infection. The parents didn’t share the exact reason. According to his medical record, his “major organs failed.”

Yekaterina, 34 years old, lost her baby at 38-39 weeks

“I didn’t even hear his first cry. I immediately realized they were resuscitating him. They were resuscitating him for a long time. They took me out and he still wasn’t crying. I lay there for a while, still under the drugs they gave me, and only did they bring me a blue tag. That was all I had been waiting for — it meant he was alive. Yes, on oxygen (as they explained later), yes, struggling, but alive. We started in Odessa (in intensive care) for a month. He was on oxygen the whole time. At the beginning of February he was born, and on March first, he died.”

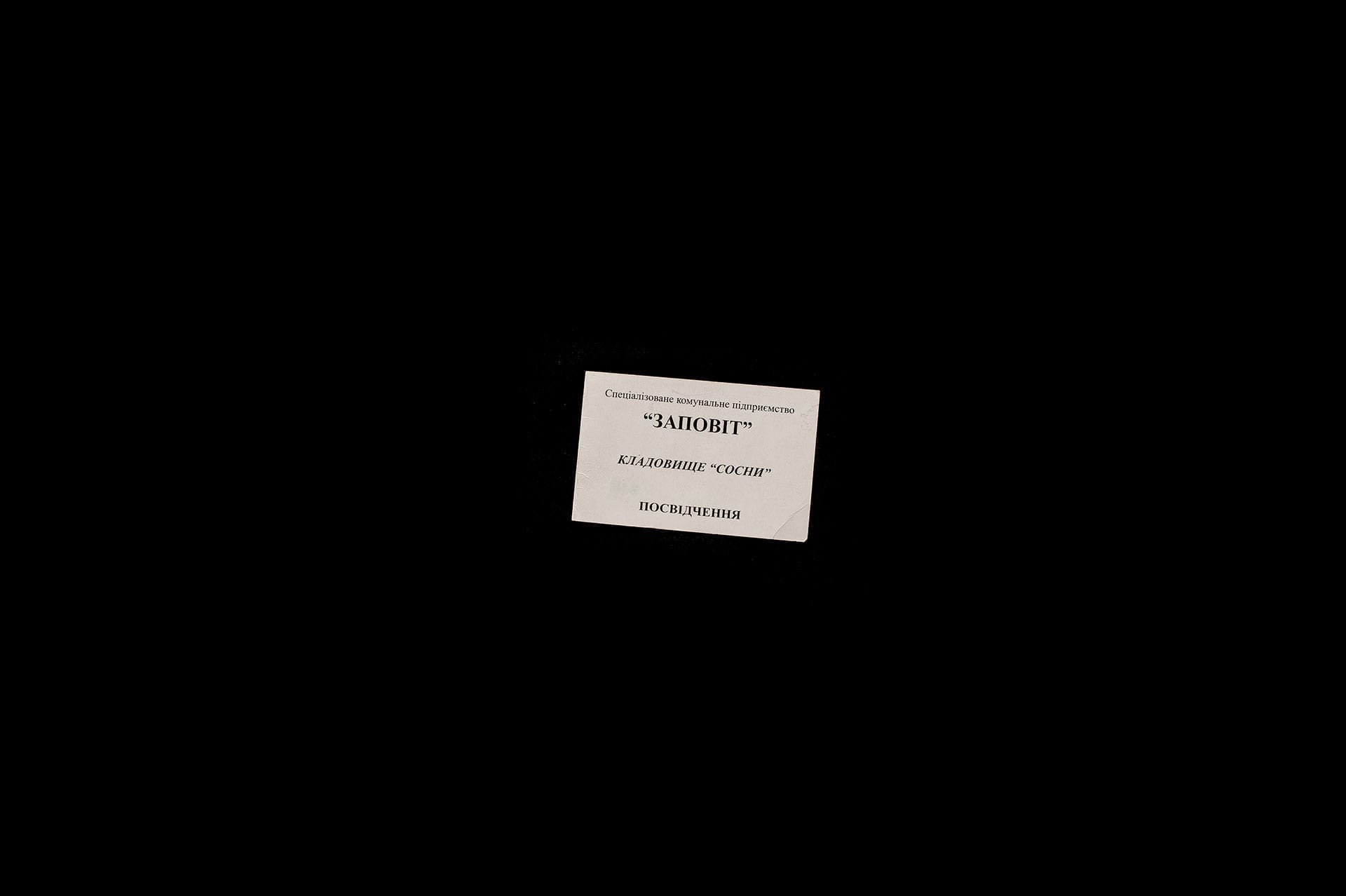

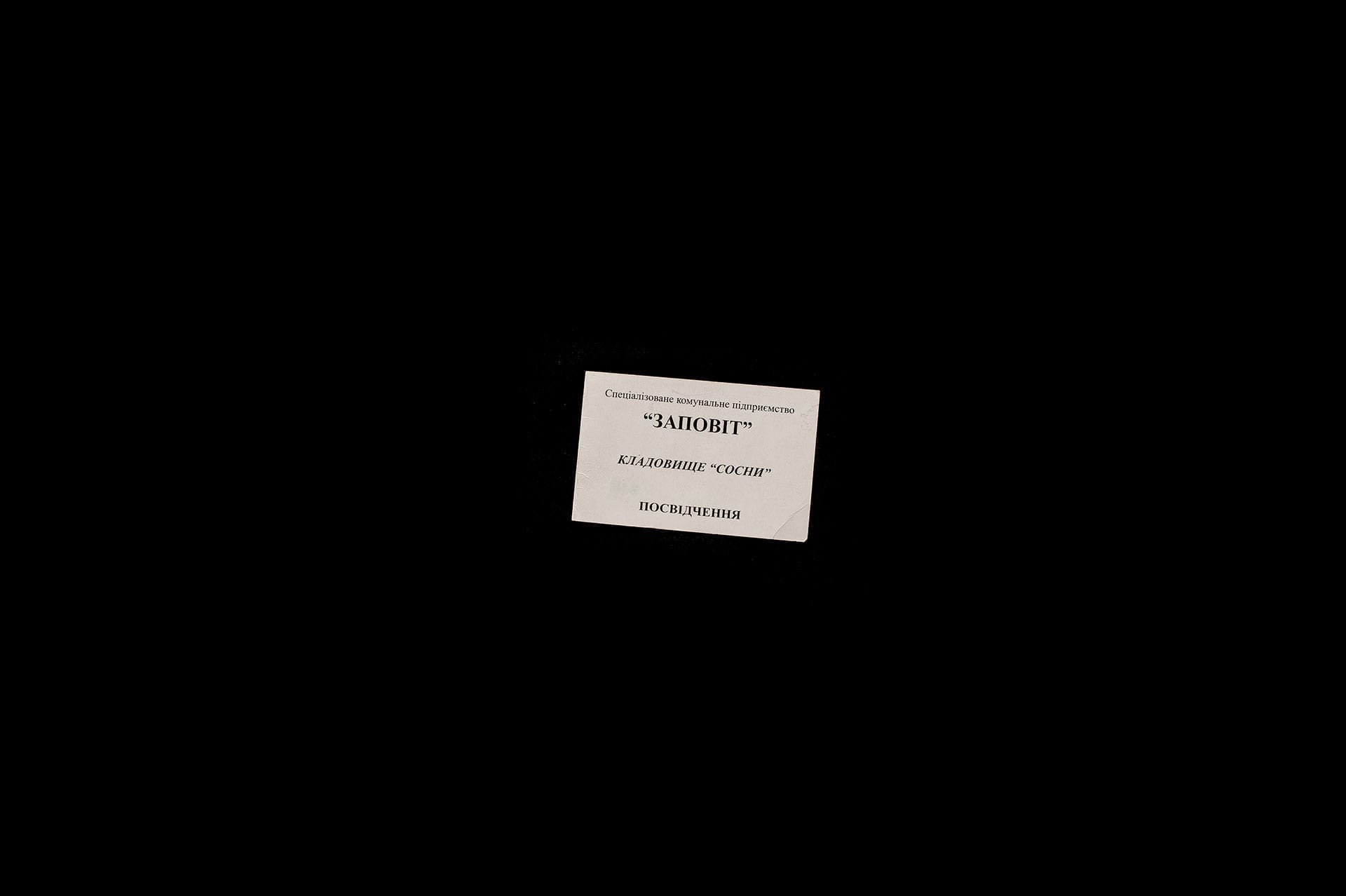

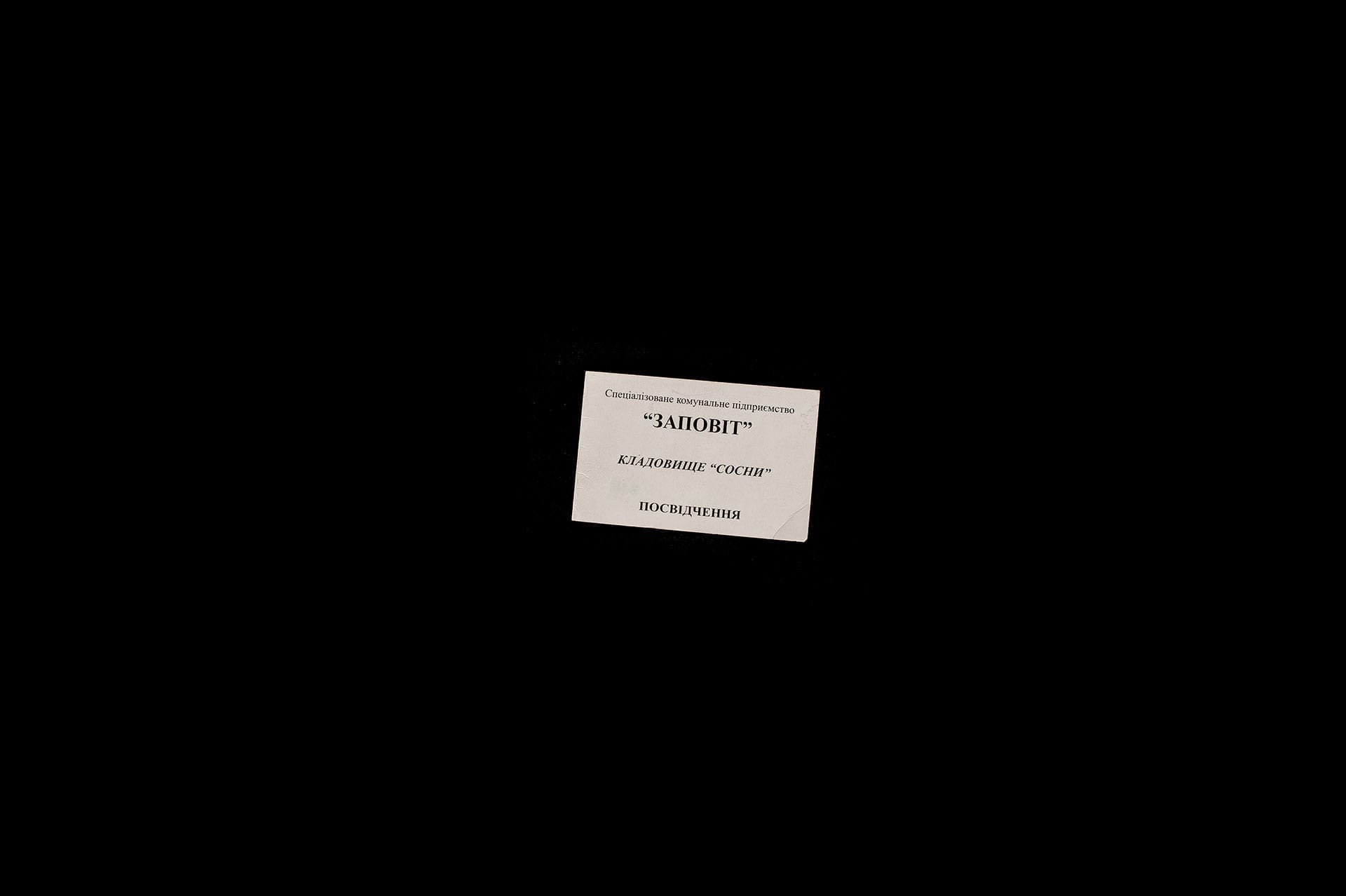

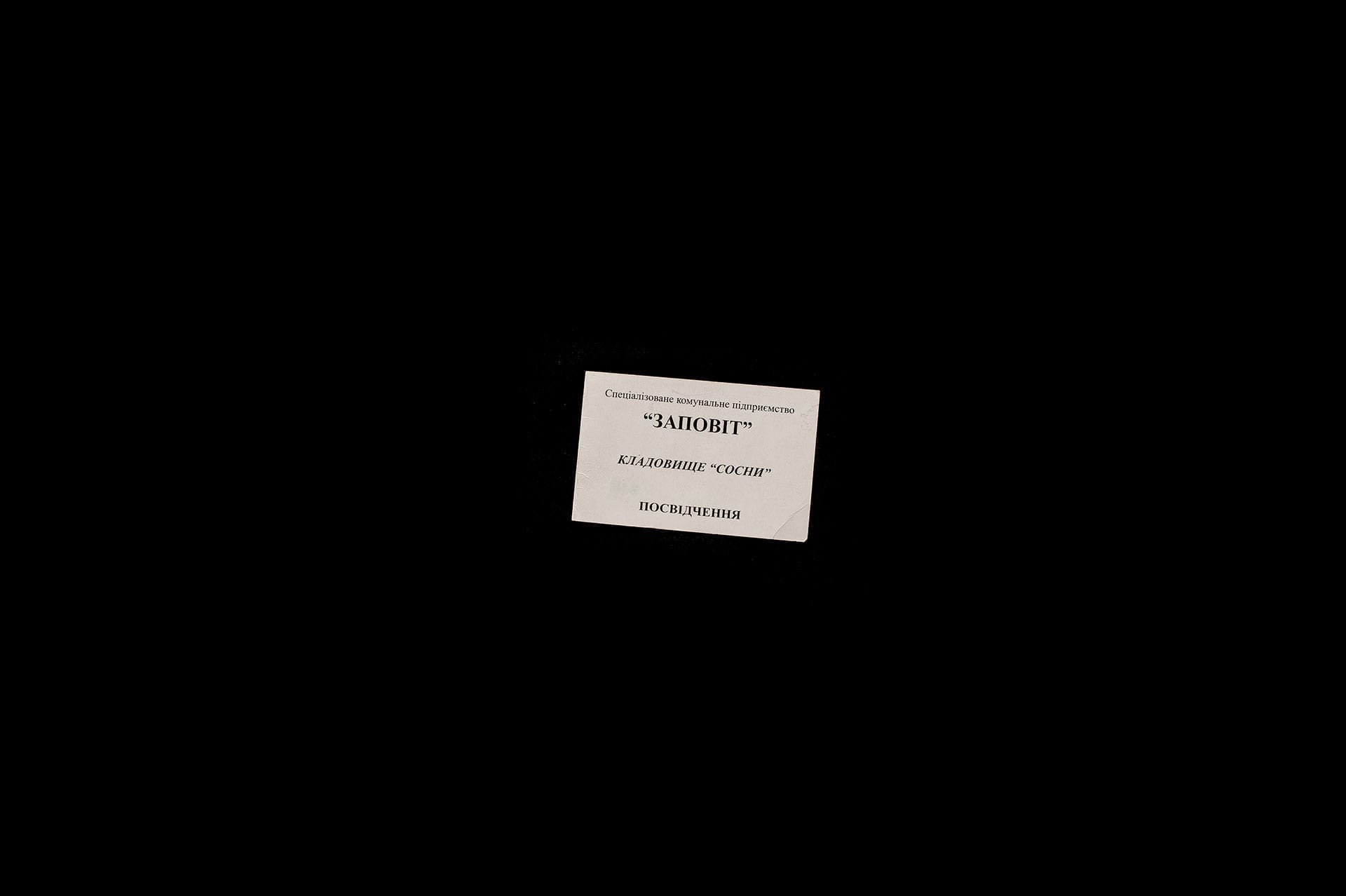

The cemetery certificate with information about the burial of “baby Goncharenko” — Vita, Elena’s stillborn son. It’s almost the only thing that she has left from that time. Her baby died in the womb at the end of the pregnancy. Doctors weren’t able to determine the cause of death — the baby had been completely healthy.

Yelena, 37 years old, lost her baby at 38-39 weeks

“I immediately signed the document saying that I refused to see my son after his birth. I just can’t imagine it: I couldn’t do that. I was so scared — where do I look at him, how?! It all happened too suddenly. My husband did the burial. I was only able to go to his grave ten years later, after my second son was born. For some reason, it let me go. And I decided to finally visit the grave”

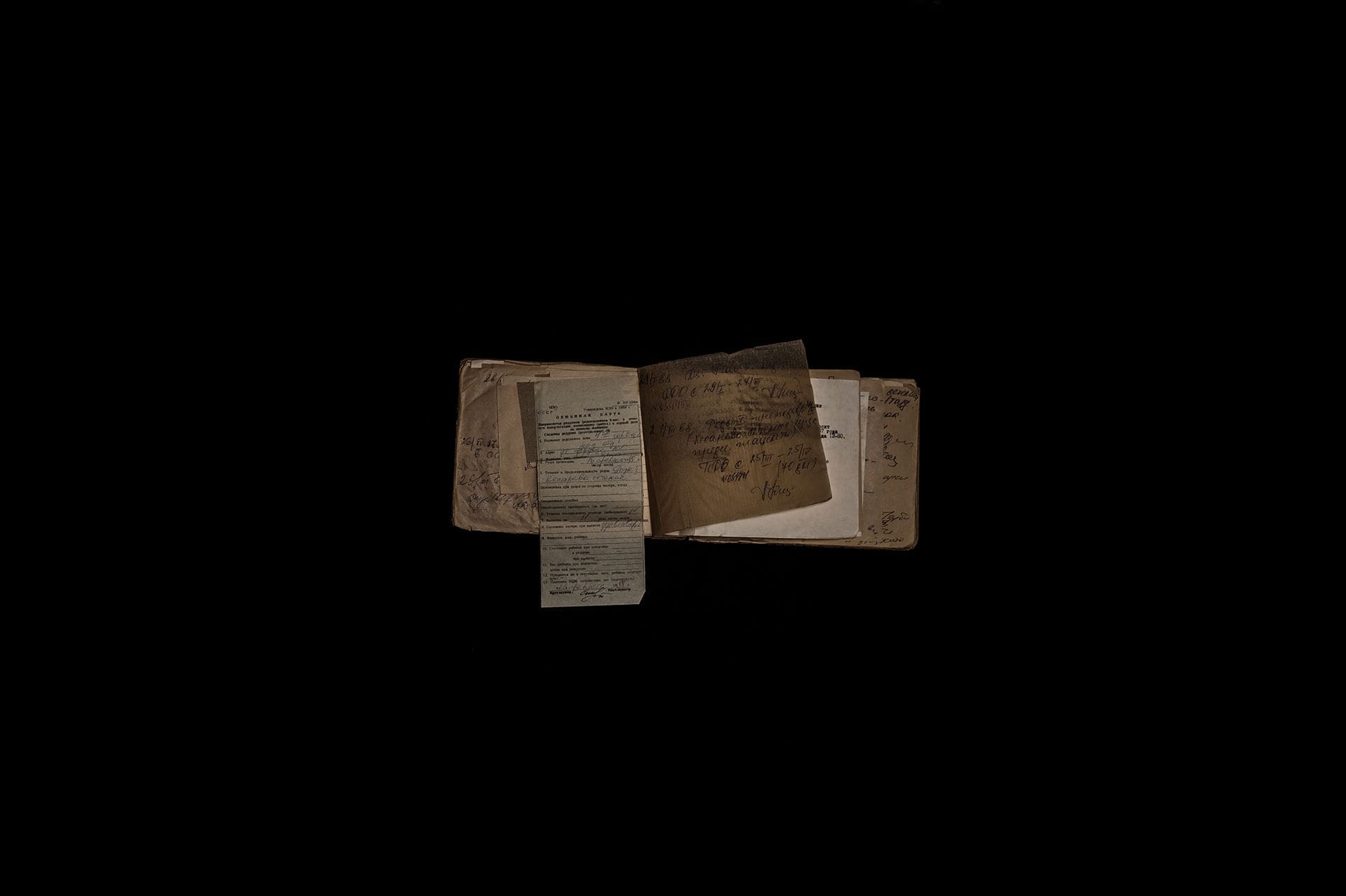

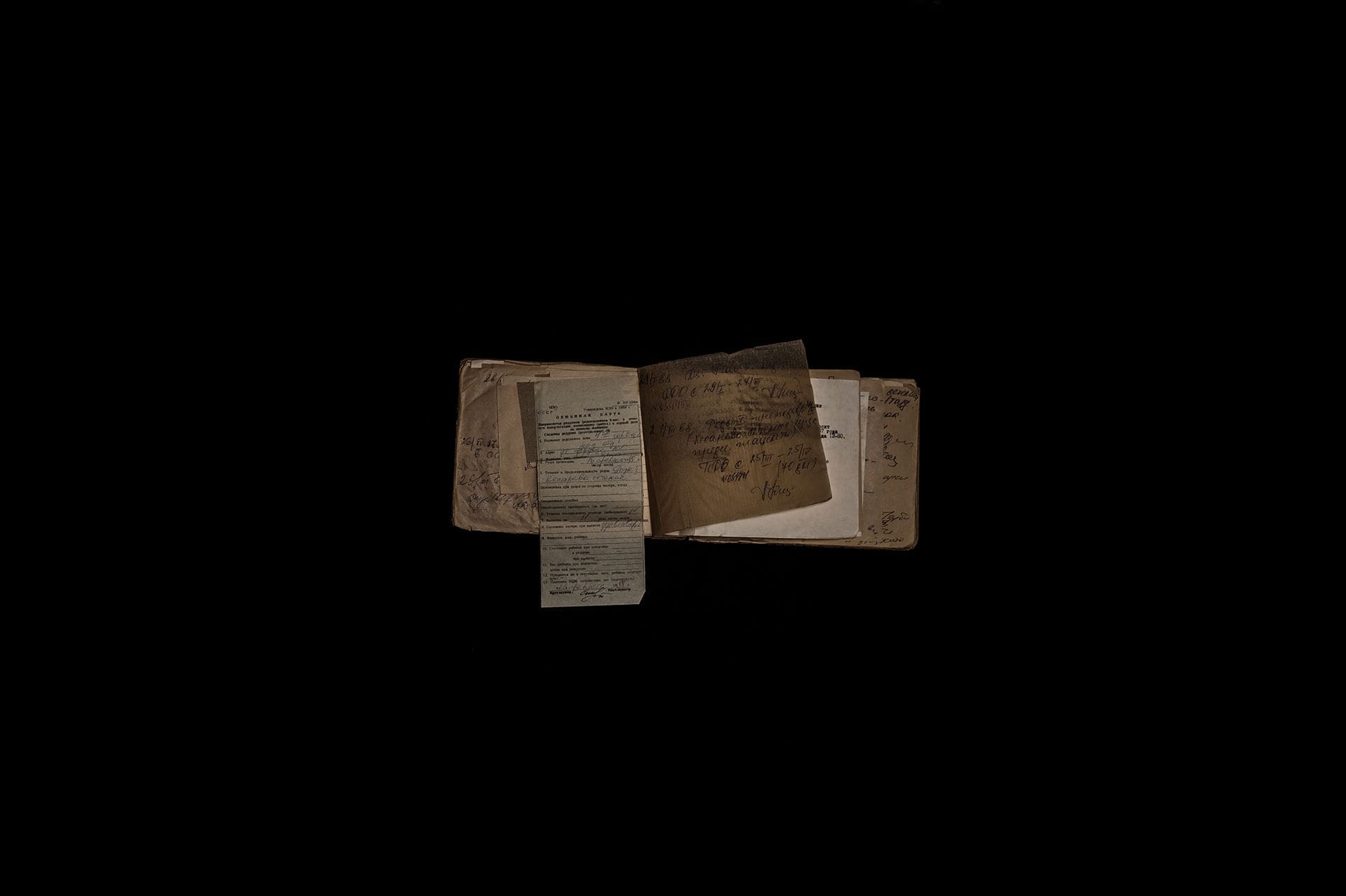

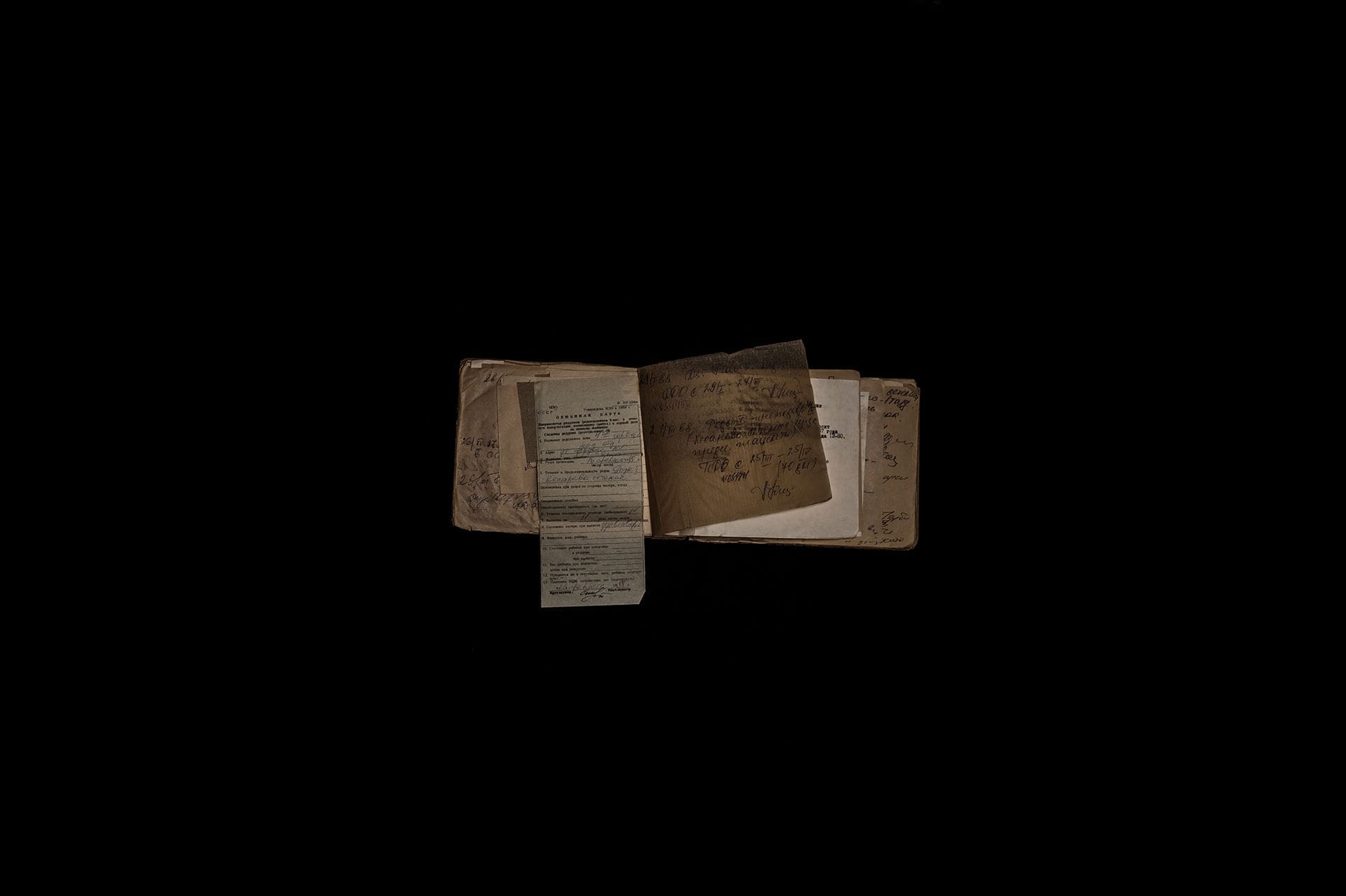

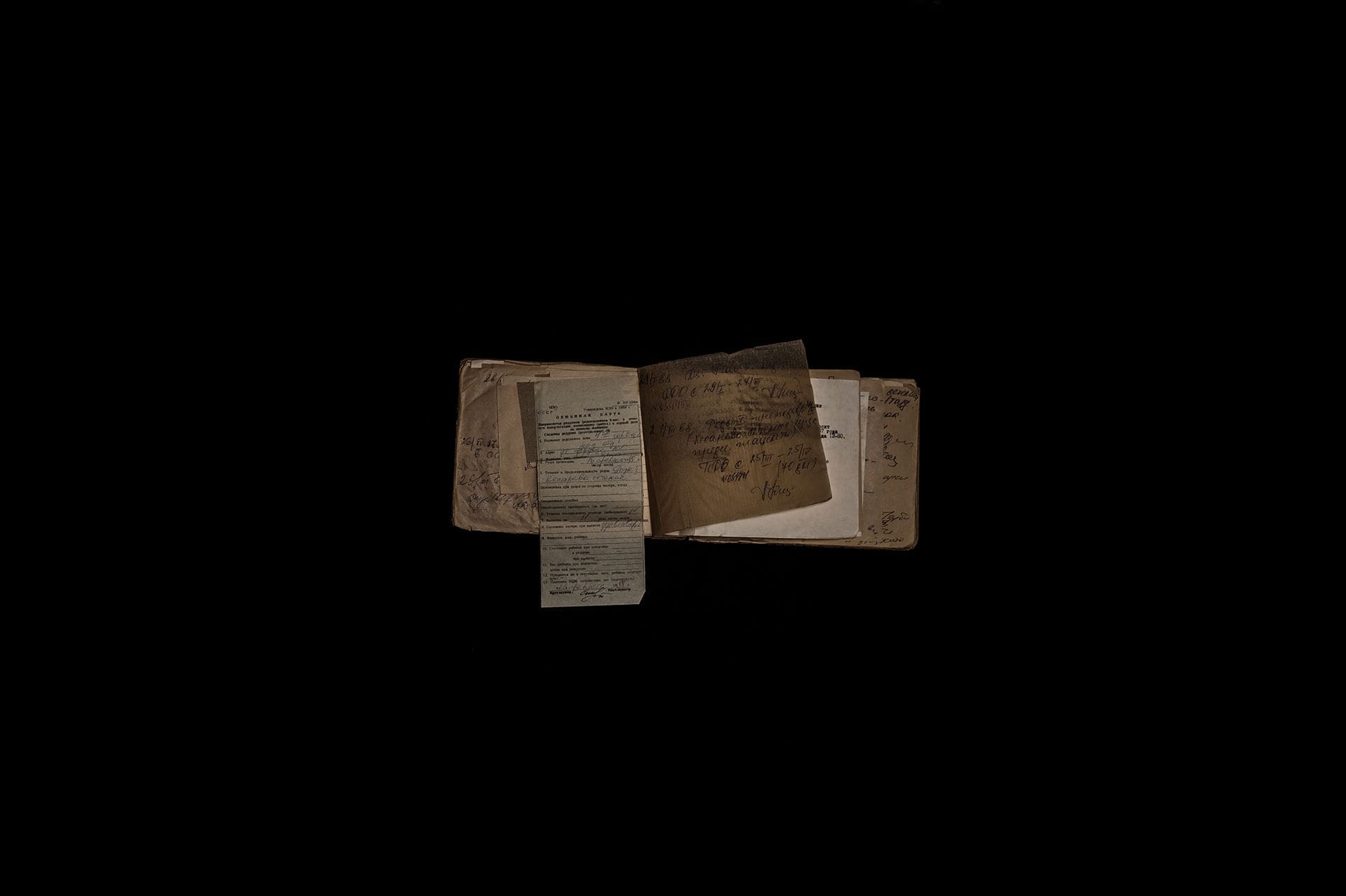

A medical chart and with a discharge slip from the hospital. From this form, Antonina learned that two months earlier she had given birth to a baby girl who weighed 2 kg. Thirty years ago during a premature pregnancy in the seventh month, Antonina lost her child, most likely due to a doctor’s mistake. After surgery, they didn’t show Antonina her baby. Two years later she gave birth to another premature boy.

Antonina, 50 years old, lost her baby at 32 weeks

“After the operation I was moved to the postpartum wing, and then they moved me from the women in labor to the pregnant women. Probably so I wouldn’t see the little babies. My chest was tightly wrapped up. The milk had to be burned because there was nobody to drink it. They held me in the hospital for 11 more days, that was it — time to go. I especially remember one nurse who was constantly saying: ‘what’s there to be upset about? You’ll have a thousand more babies like that, and three thousand abortions after that.’ Yeah, a thousand, I thought, of course.”

House slippers that Alyona took with her to the surgery to terminate her ectopic pregnancy. The shirt and shoes are all she has left from that day. On the 12th week of her long-awaited pregnancy, Alyona learned that he would have to get rid of her baby. The location of the fertilized egg wasn’t diagnosed in time, which threatened Alyona’s life and required emergency surgery.

Alyona, 30 years old, lost her baby at 12 weeks

“After the operation, I immediately suggested that we get divorced. He replied that he didn’t take me as his wife to “give me back later,” and we didn’t talk about it again. His relatives insisted that I would have a “difficult period.” But I remember how nobody was in a hurry to make me feel better. Everyone pretended that nothing had happened. She just had surgery, she just got sick.

“Zero Censorship” is a space for open dialogue about difficult and taboo topics like sexuality and bodies, stress and depression, war and identity. We don’t pay royalties, but we help amplify our authors’ voices. Details here.

Translated by Sam Breazeale from Respond Crisis Translation.

Yulia, 36 years old, lost her baby at 48 weeks

“Some people say, ‘I don’t want to ask because I don’t want to remind you.’ Remind me? Seriously? I’m thinking about it 24 hours a day. There’s not a moment when I don’t remember my baby. Even after having two healthy children, I still remember Lyosha every day.”

Baby Aleksey’s onesie. The boy was born prematurely at 28 weeks and lived a little over a month. Yulia saved a few of his things in memory of him.

Olga, 33 years old, lost her baby at 24 weeks

“The doctors asked whether we wanted to take the body. Of course, of course we did! They don’t even make such small coffins. They put him in a child’s one, but it swallowed him up, he was so small. I know that in the States you can bury a nine- or ten-week-old, but here he’s not even considered a person before 22 weeks. And they won’t save him. I understand that from a professional perspective it’s probably not possible, but to call a dead child ‘medical waste’ — it’s awful.”

Baby Yegor’s hat and socks. He was born prematurely at 24 weeks and lived eight days. His mom and dad called him a “little Smurf” because of this blue hat, which they put on him when he was in the ICU. Olga keeps his things in memory of him.

Yekaterina, 34 years old, lost her baby at 38-39 weeks

“I didn’t even hear his first cry. I immediately realized they were resuscitating him. They were resuscitating him for a long time. They took me out and he still wasn’t crying. I lay there for a while, still under the drugs they gave me, and only did they bring me a blue tag. That was all I had been waiting for — it meant he was alive. Yes, on oxygen (as they explained later), yes, struggling, but alive. We started in Odessa (in intensive care) for a month. He was on oxygen the whole time. At the beginning of February he was born, and on March first, he died.”

Baby Artyom’s ID tag, which Katya kept in memory of her son. He died soon after being born because of an infection. The parents didn’t share the exact reason. According to his medical record, his “major organs failed.”

Yelena, 37 years old, lost her baby at 38-39 weeks

“I immediately signed the document saying that I refused to see my son after his birth. I just can’t imagine it: I couldn’t do that. I was so scared — where do I look at him, how?! It all happened too suddenly. My husband did the burial. I was only able to go to his grave ten years later, after my second son was born. For some reason, it let me go. And I decided to finally visit the grave”

The cemetery certificate with information about the burial of “baby Goncharenko” — Vita, Elena’s stillborn son. It’s almost the only thing that she has left from that time. Her baby died in the womb at the end of the pregnancy. Doctors weren’t able to determine the cause of death — the baby had been completely healthy.

Antonina, 50 years old, lost her baby at 32 weeks

“After the operation I was moved to the postpartum wing, and then they moved me from the women in labor to the pregnant women. Probably so I wouldn’t see the little babies. My chest was tightly wrapped up. The milk had to be burned because there was nobody to drink it. They held me in the hospital for 11 more days, that was it — time to go. I especially remember one nurse who was constantly saying: ‘what’s there to be upset about? You’ll have a thousand more babies like that, and three thousand abortions after that.’ Yeah, a thousand, I thought, of course.”

A medical chart and with a discharge slip from the hospital. From this form, Antonina learned that two months earlier she had given birth to a baby girl who weighed 2 kg. Thirty years ago during a premature pregnancy in the seventh month, Antonina lost her child, most likely due to a doctor’s mistake. After surgery, they didn’t show Antonina her baby. Two years later she gave birth to another premature boy.

Alyona, 30 years old, lost her baby at 12 weeks

“After the operation, I immediately suggested that we get divorced. He replied that he didn’t take me as his wife to “give me back later,” and we didn’t talk about it again. His relatives insisted that I would have a “difficult period.” But I remember how nobody was in a hurry to make me feel better. Everyone pretended that nothing had happened. She just had surgery, she just got sick.

House slippers that Alyona took with her to the surgery to terminate her ectopic pregnancy. The shirt and shoes are all she has left from that day. On the 12th week of her long-awaited pregnancy, Alyona learned that he would have to get rid of her baby. The location of the fertilized egg wasn’t diagnosed in time, which threatened Alyona’s life and required emergency surgery.

“Zero Censorship” is a space for open dialogue about difficult and taboo topics like sexuality and bodies, stress and depression, war and identity. We don’t pay royalties, but we help amplify our authors’ voices. Details here.

Translated by Sam Breazeale from Respond Crisis Translation.