Kharkiv photography is a unique movement in the history of Ukrainian art. Kharkiv authors are better known outside the country, and their cultural heritage has not yet been properly studied and recognized at home. Zaborona editor-in-chief Kateryna Sergatskova attended the opening of the first collective exhibition of representatives of the Kharkiv School of Photography, visited the KhShF Museum under construction and explains why everyone should know about this particular school of photography.

The Kharkiv School of Photography, which was actively developing during the period of stagnation and collapse of the Soviet Union, greatly influenced many important players in contemporary art. The names of the members of the KhShF – such as Boris Mikhailov or Serhiy Bratkov – are known all over the world, and their works are in the collections of the largest art institutions. This spring, experts from the Georges Pompidou Center selected 131 works by authors representing the Kharkiv School of Photography for their collection. In 2022, a large exhibition dedicated to Ukrainian photography will be held in Paris. This will be the first time that the brightest movement of Ukrainian art will be shown to a global audience at this level.

The work of “Rapid Response Group,” the exhibition “The Author in the Game: Kharkiv School of Photography.” Photo: Oleksander Osypov

On May 28, an exhibition entitled “Artist in the Game,” organized by the Museum of the Kharkiv School of Photography, opened at the Yermilov Center, a contemporary art center, in Kharkiv. For the first time, representatives of different generations of the KhShF found themselves in the same space. Nadezhda Bernard-Kovalchuk, the author of the monograph “Kharkiv School of Photography: A Game against the Machine” and co-curator of the exhibition, says that it was important to unite the authors with a common symbolic field and show that the traditions laid down by the School are still alive.

Members of the Kharkiv School of Photography at the opening of the exhibition at the Yermilov Center. Photo: Oleksander Osypov

Also – to declare that this movement has long deserved the attention of Ukrainian researchers and viewers, because its scale, influence and power go far beyond the borders of the country. And yet, the School is barely mentioned in Ukraine itself. In 2013, the Yermilov Center hosted the first retrospective of Boris Mikhailov, the only Ukrainian artist who exhibited at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, for the first time since independence. In 2019, an exhibition dedicated to the Kharkiv School of Photography was held at the Pinchuk Art Center, but it was criticized due to the fact that even half of the participants in the movement were not represented there.

Boris and Vita Mikhailov (center) in the “graduation album” of the “Author in the Game” exhibition. Photo: Oleksander Osypov

Artist in the Game

The Kharkiv School of Photography was founded in 1971 on the basis of the Kharkiv Regional Photo Club, headed by Herman Dryukov. The club operated according to the same rules as throughout the Soviet Union: it united amateur photographers who once a week gathered at the Palace of Trade Unions, discussed each other’s photographs, and sent them to the Soviet Photo magazine. The photographs were to be approved by Soviet propaganda offices and were created in the official style of socialist realism. However, everything changed when Boris Mikhailov, Evheniy Pavlov, Yuri Rupin, Oleh Malevany, Oleksander Suprun and Hennadiy Tubalev met each other at the club’s meetings. They formed the independent group Vremya – and forever changed the rules of the game in both Soviet and contemporary world photography. The basis of their method was the “theory of impact.”

These photographers could spend hours discussing the role of photography, the boundaries of the image, and its impact on the viewer. Over the course of their discussions, they came to a method in which the main thing is to stun, surprise, “hit” the viewer so that they understand something important about the reality in which the image exists. Of course, this approach ran counter to the official aesthetics of socialist realism, which was invented by the Soviet ideological elite to replace reality with ideal images of “victorious socialism.”

Members of the Vremya group constantly experimented with objects of photographic research and formal methods. For example, Mikhailov came up with a method of overlaying pictures, which he called a “sandwich”: in it, two images (for example, a dull cityscape and a naked man) are superimposed on each other to create a new meaning. All members of the group made collages, color photographs and created a series of specific phenomena or events.

When the group broke up, and the photo club was closed due to the photographers ‘radical’ approaches, the second generation of the Kharkiv photography school appeared, which, together with the first, continued these experiments. The “Rapid Response Group”, as they called themselves, emerged during the collapse of the Soviet Union. Boris and Vita Mikhailov, Serhiy Bratkov and Serhiy Solonskiy were part of this second wave. Its main method was performance and artistic provocation. Researcher Nadia Bernard-Kovalchuk says the group worked with both videos and installations, going far beyond photography, but leaving it as the basis.

Triptych “If I were German …” – documentation of a performance organized by the “Rapid Response Group” in 1994. Photo: Oleksander Osypov.

“Three generations of the Kharkiv School of Photography, especially Boris Mikhailov, developed methods that continue to be used to this day,” says Serhiy Lebedinsky, a member of the Shilo group (the third generation of the Kharkiv School of Photography) and founder of the Museum of the Kharkiv School of Photography.

Arguments about the School

“Well, why are we watching other people get drunk?” – asks a girl at the opening of the Artist in the Game exhibition. In front of her is the documentation of the 1996 performance, in which representatives of the first and second generations of the Kharkiv School of Photography participated. In a video filmed by Andrey Avdeenko, colleagues accompany Boris Mikhailov to Germany: the artist left Kharkiv for Berlin, where he lives to this day. Documentation of the actions of the Kharkiv photographers who share the “theory of impact” has become one of the important methods of the Kharkiv photography school. The girl is perplexed. Meanwhile, Andrey Avdeenko is standing a meter away from her.

There is a lot of controversy surrounding the Kharkiv School of Photography. One of the main questions is whether the school was a movement – since it is not an institution. In her monograph, Nadezhda Bernard-Kovalchuk proves that it was. Serhiy Lebedinsky claims that it still exists, since the methods invented by its members continue to be applied, and there is continuity.

There is also another controversy: who should be included in the Kharkiv School of Photography? Some photographers do not call themselves the school’s followers, but researchers rank them as part of the School. Others, on the contrary, consider themselves followers of the School, but doubt their belonging to it – especially when it comes to photographers who have never lived in Kharkiv.

“There are two ways,” says Serhiy Lebedinsky. “You can become a member of the Kharkiv School of Photography either by love or science. If a person declares that he follows the methods of Kharkiv photographers, then he becomes a member of the KhShF ‘by love.’ If a person does not believe that they are a follower of the KhShF, but the researchers know that they were inspired by it and used the same methods, then they are counted as being a follower ‘by science.’”

Lebedinsky resolved this key dispute at the opening of the “Artist in the Game” exhibition by cutting a red ribbon in front of a symbolic object – a school graduation album. In the tradition of Soviet school photography, the curators placed in oval frames the portraits of everyone who is usually considered to be among the three generations of the KhShF: from Boris Mikhailov (first generation) and Serhiy Bratkov (second generation) to the duet of Danil Revkovsky and Andrey Rachinsky (third generation).

Serhiy Lebedinsky cuts the ribbon at the opening of the exhibition in the Yermilov Center. Photo: Oleksander Osypov

The museum-laboratory

Until the mid-2010s, the Kharkiv School of Photography was the focus of a rather narrow circle of cultural experts, researchers, and artists. Archives of Kharkiv photographers were mostly gathering dust at home or in studios, and some series’ by that time had been completely destroyed or lost. At the same time, Boris Mikhailov had become a laureate of some of the most prestigious world awards in art (The Hasselblad Foundation International Award in Photography and Goslarer Kaiserring Award), and his works had been exhibited in major art centers around the world.

The situation began to change when a member of the Shilo group (third generation of the KhShF), photographer Serhiy Lebedinsky, decided to create the Museum of the Kharkiv School of Photography. At first, he says, he had the desire to collect photographs of his colleagues and create their own archive of all the artists of the KhShF.

“I came with this idea to Serhiy Solonsky and offered to buy several photographs from him,” says Serhiy Lebedinsky. “The work lay in the dust for years in his studio, no one was doing anything with them. And I decided that it was necessary to more actively gather all the artists of the Kharkiv school, to promote and show them everywhere – and this requires a foundation. But how can you do this without having a lot of money, and also, so that the artists don’t tell you to go to hell, and that what they’ve entrusted you won’t be lost? ”

This is how the public organization “Museum of the Kharkiv School of Photography” appeared. Its staff included, in addition to Lebedinsky, researchers Nadezhda Bernard-Kovalchuk and Oleksandra Osadchaya.

Left to right: Director of the Yermilov Center Natalia Ivanova, Serhiy Lebedinsky, Nadezhda Bernard-Kovalchuk,

member of the “Shilo” group Vladyslav Krasnoshchek and Oleksandra Osadchaya. Photo: Oleksander Osypov

But the museum could not exist for long without premises. Lebedinsky persuaded his parents to give him part of the brick building of the Manometer factory, which was built at the beginning of the 20th century and served as a railway laboratory. Now this plant produces pressure sensors and belongs to the family of the photographer.

Serhiy and his family are investing their own funds into the renovation of the attic of the building, for an exhibition hall. Part of the office space will be used as a repository for archives, part will be used for an open library, conference room and space for museum researchers. In addition, the plant complex has a hangar and warehouses, which, according to Lebedinsky, will also be subordinated to museum purposes as much as possible.

“The creation of a museum requires too much money we don’t have,” says Lebedinsky. “But little by little, we are doing something on our own. When we finish the museum itself, questions will arise, for example, of the bad road that leads to us, someplace where a visitor could drink coffee, and so on.”

Troch’s suitcase

The museum has already published photo books by Viktor and Serhiy Kochetov, Oleksander Chekmenev and Serhiy Melnychenko, as well as a monograph by Nadezhda Bernard-Kovalchuk. Photo books of other authors from the collection of the museum and the study of archives will be published in the future.

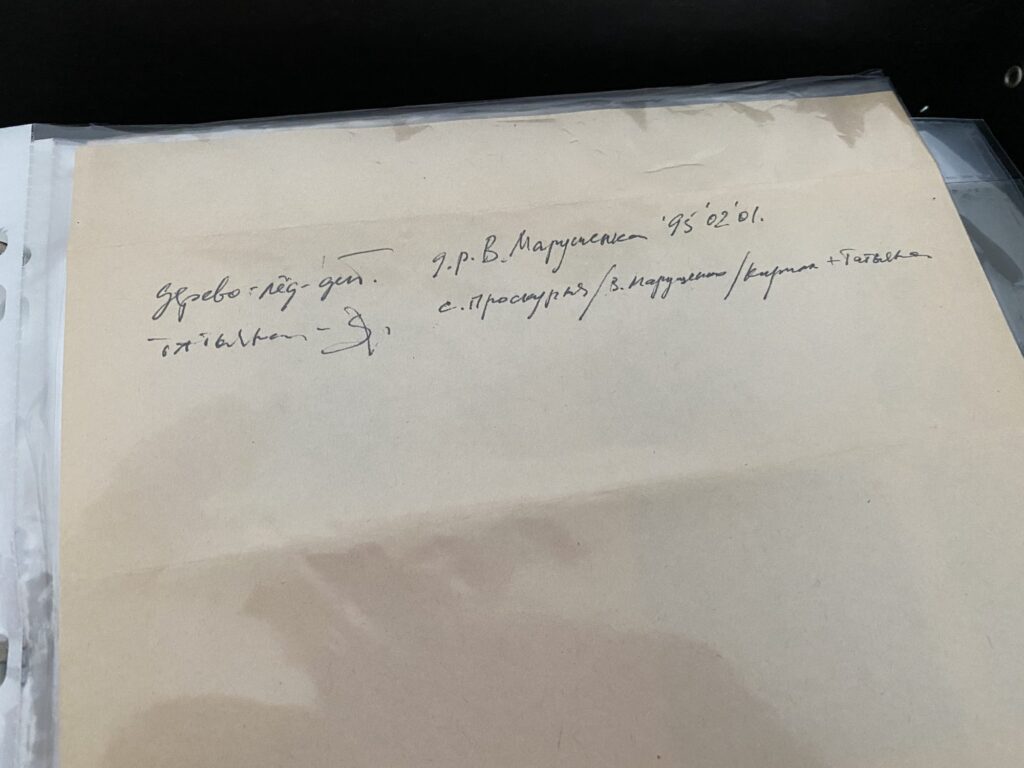

Depository at the Museum of the Kharkiv School of Photography. Photo: Kateryna Sergatskova

Archives are the most interesting thing in the future work of the museum. Recently, with the support of the photographer Chekmenev and cultural manager Iryna Osadchay, the collective was able to receive the famous “Trokh’s suitcase” – the archive of the Kyiv photographer Mykola Trokhymchuk. He was one of the prominent representatives of the Paris Commune artist community, working in the genre of photo collage and staged photography, following the tradition of American photographers Helmut Newton and Peter Joel Witkin.

He died of a heart attack in 2007, leaving behind a huge, chaotic set of footage. Most of these pictures have never been printed. After his death, there was a legend that someone had “Troch’s suitcase” with this archive, which was allegedly lost.

“Now we have this ‘suitcase’,” says Lebedinsky.

Bernard-Kovalchuk considers the current situation to be unique: most of the classics of the Kharkiv school of photography are alive and can talk about what their times were like, how Soviet and post-Soviet reality changed through the prism of their views.

Nadezhda Bernard-Kovalchuk at the opening of the exhibition “Artist in the Game: Kharkiv School of Photography.” Photo: Oleksander Osypov

“As long as it is possible to archive everything and record the voices of the authors, we need to do it as quickly as we can,” she says. “Otherwise, the archives will burn and access to the modern history of our country will be interrupted. Therefore, the museum is private, and we do that because we are personally responsible for the work of these photographers, and understand their value. ”

“Collage panopticon” by Serhiy Solonsky in the repository of the Museum of the Kharkiv School of Photography. Photo: Kateryna Sergatskova

Lebedinsky says that the main goal of the museum is for anyone who comes to Kharkiv to first of all go to see the Kharkiv School of Photography and Boris Mikhailov. “The legacy of the most striking phenomenon in Ukrainian art should be available to everyone,” says the photographer.

Translated by Ismatullo Rahimov from Respond Crisis Translation