The annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas did not cause decisive condemnation actions of the so-called collective West — mild sanctions affected Russian business, but did not contribute to the breakdown of business relations and the boycott of the Russian presence in Europe. In 2022, everything changed: not only Russian diplomats and businessmen but also artists, writers, and cultural figures became unwanted persons. Among them were Russian artists and gallerists who were asked not to participate in the Austrian Vienna Contemporary art fair. This year, the organizers also asked a Russian oligarch to step down as owner and provided more stands for Ukrainian art. You can learn about who currently curates Vienna Contemporary, why Russian gallerists are afraid to speak out against the war, and whether to wait for a boom in Ukrainian art from the article by Zaborona’s editor-in-chief Kateryna Serhatskova.

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, European countries were filled with Russian cultural projects. Troupes of the Bolshoi Theater toured Europe, huge stands of Russian publishing houses stood at book fairs, and Russian artists exhibited in key museums and galleries. Despite the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas, which Russia has been waging through its proxy forces since 2014, the cultural arena remained outside of politics and sanctions. The invasion, which began on February 24, changed everything.

-

Photo: Anatoliy Babiychuk / Zaborona

Since 2012, the Vienna Contemporary International Art Fair, one of the important autumn cultural events in Central and Eastern Europe, has belonged to the Russian multimillionaire, owner of the RDI Group development company, Dmitry Aksenov. In an interview with Russian Forbes in 2019, he explained that he invests in art markets because “people need confidence and orientation in the cloud of informational garbage that surrounds us, and culture acts as a certain beacon that helps to understand what is good, and what’s bad.”

The millionaire also said that he chose Vienna because “the cultural content of this [Eastern European] region is undervalued either economically or culturally for objective reasons: we have been cut off from global evolution for a long time.” But based on how the RDI Group corporation positions itself on its website, investment in art is a tool for creating a positive company brand, including for a successful presence in Western markets.

-

President of Austria (2004-2016) Heinz Fischer and Dmitry Aksenov at the Vienna Contemporary opening in 2014. Photo: Manfred Schmid/Getty Images

But this was not the only reason. Most of the galleries participating in the fair were Russian, and they were often given the best places. While the audience looked at the art, Russian politicians and businessmen discussed matters on the sidelines of art events. According to the fair tradition, Vienna Contemporary was also used by them as a background for business negotiations.

At the beginning of the invasion, his old friend, the director of Vienna Contemporary, Markus Huber, met Dmitry Aksenov in Vienna. He said that the art house can no longer have a Russian millionaire as its owner. In a conversation with Zaborona, Huber said that Aksenov reacted “with understanding”, although he was “frustrated” by what was happening in Ukraine. And so the “de-oligarchization” of Vienna Contemporary began.

“We have always had a commitment to Ukraine,” says Vienna Contemporary director Markus Huber. “Even last year, we thought about excluding sole ownership of the fair and including Austrians as co-owners. And when the war started, we reacted quickly and made a public statement [condemning Russia’s actions], which few cultural institutions in Vienna did.”

-

Markus Huber during the “Ukrainian culture on its way to the EU” panel discussion as part of Vienna Contemporary 2022. Photo: Anatoliy Babiychuk / Zaborona

According to Huber, the management of the art fair had a conversation with the numerous Russian galleries that were previously represented at the event on the topic that they would not be able to participate in the fair this year unless they made a public statement against the attack on Ukraine.

“I know some of them are against the war, but that’s not enough. I turned to them and said that I understand that it is difficult to do in Russia, but it is not difficult to do if you come to Austria,” says the director of the art fair.

Huber adds that none of the Russian gallerists ever made a statement condemning the actions of their own country, however, during the conversations, their curators “spoke more about the problems they face in Russia, and never once mentioned Ukraine.”

At the beginning of the invasion, in February, Yana Barinova, the head of the Kyiv city administration’s culture department, along with her 13-year-old daughter, evacuated from Kyiv due to the danger of the capital being captured by Russian troops. Because of this, the mayor of the city Vitaliy Klitschko fired her — she sued him (and won). Soon she was invited to become the program director of Vienna Contemporary and the ERSTE Foundation artist support fund, which was considering the possibility of the financing part of the art fair’s activities. Together with the director of the fair, Markus Huber, Barinova is supposed to start the process of “restructuring” Vienna Contemporary after the exclusion of the Russian millionaire from the owners.

-

Boris Ondreička (Bratislava), Alexandra Grausam, Yana Barinova, Kateryna Filiuk. Photo:Anatoliy Babiychuk / Zaborona

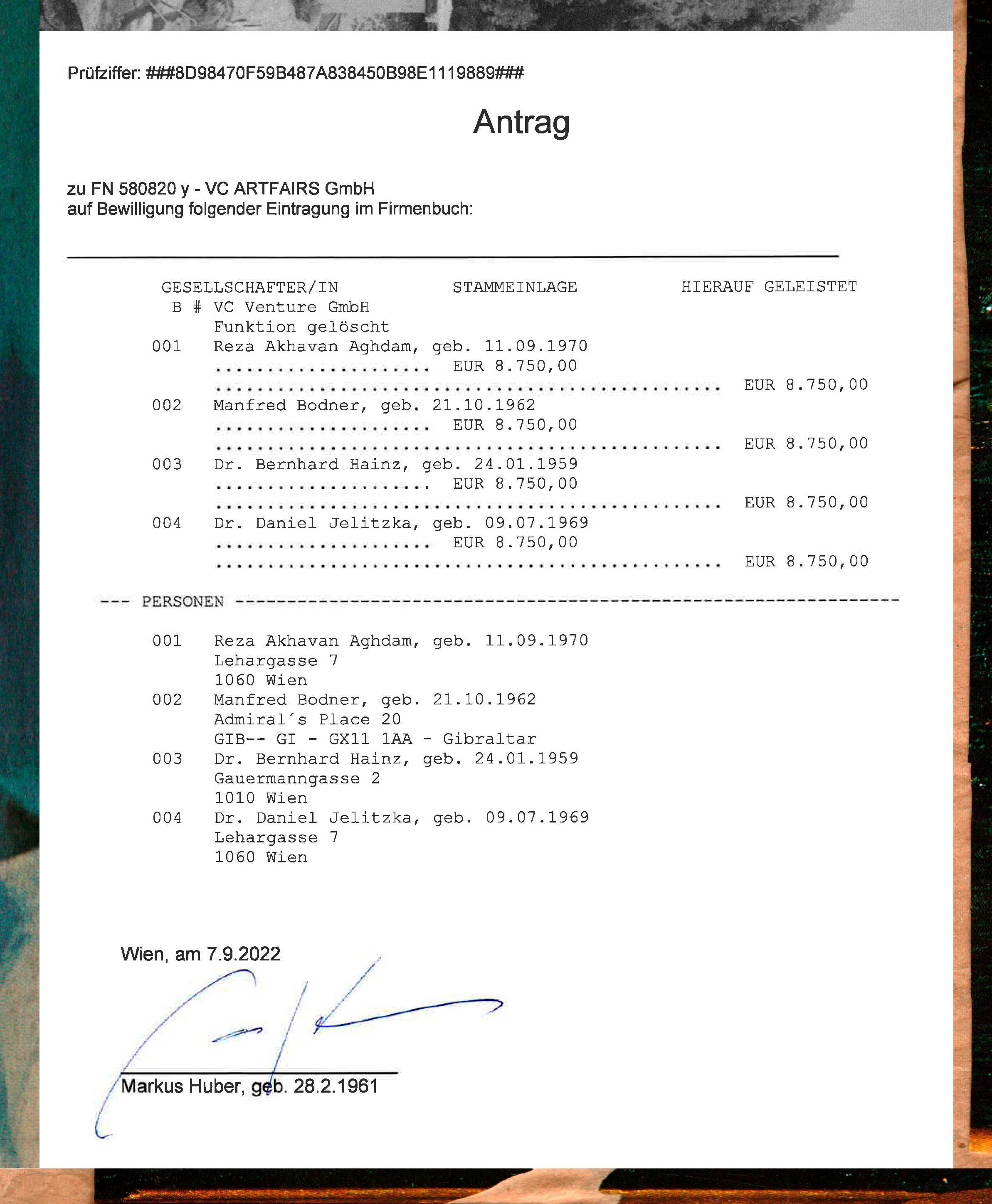

On the eve of the official opening of the art fair, a document appeared, which shows that the new owners of Vienna Contemporary are equally four people, three of whom are businessmen from Vienna, and one is an entrepreneur registered in Gibraltar. Director Markus says he hopes that now “Ukrainian narratives [in Austria] will be heard.”

-

Document with information about the new owners of Vienna Contemporary

“Even I didn’t know that Kazimir Malevich had Ukrainian roots,” says Markus Huber. “Because he was told that he is Russian. But now this [Ukrainian] story must be told.”

In recent months, Ukrainian artists, cultural managers, and diplomats have repeatedly spoken publicly about the need to boycott Russian culture in Europe because of the invasion. Ukrainian film director and critic Oleksiy Radynsky expressed the opinion that “Russian culture deserves more punishment than a boycott — it deserves deconstruction.” Some European politicians do not agree with this, but the presence of Russian, even oppositional, artists and organizations at European events creates tension.

For a long time, Russian culture was fueled by big money from oligarch sponsors, who used their assets to wash away the dirty image behind their capital. Ukrainian cultural manager, curator of the Culturescapes Festival (Switzerland), Kateryna Botanova, in a conversation with Zaborona, says that art in Russia to some extent reflects relations with big capital, unlike Ukrainian art, which, having lost many connections with Moscow after 2014 — and, respectively, with capital, began to develop in a completely different direction. Artists who were cut off from large resources had to focus on making more inventive decisions, focusing on reflecting, understanding the local and global processes in which they found themselves.

-

Minister of Culture and Information Policy of Ukraine Oleksandr Tkachenko during the “Ukrainian culture on its way to the EU” panel discussion as part of Vienna Contemporary 2022. Photo: Anatoliy Babiychuk / Zaborona

-

Markus Huber and Kateryna Botanova during the “Ukrainian culture on its way to the EU” panel discussion as part of Vienna Contemporary 2022. Photo: Anatoliy Babiychuk / Zaborona -

Tania Malyarchuk and Natalia Mykolska during the “Ukrainian culture on its way to the EU” panel discussion. Photo: Anatoliy Babiychuk / Zaborona

“Austria will stand for Ukraine and support Ukrainian culture,” Markus Huber said at the opening of Vienna Contemporary.

For the first time in many years, more Ukrainian artists and cultural figures than Russian ones are represented in Vienna. Pavlo Makov, Anatoliy Belov, Kinder Album, Liya, and Andriy Dostlevy are perhaps new names for many in the European art community. In the coming years, there should be a boom in Ukrainian art and research devoted to Ukrainian culture and Russian cultural colonization policy in Europe, as it happened with the art of the countries of the Balkan Peninsula after the war in Yugoslavia.

“Art market is an amazing tactical construct,” says Vienna Contemporary director Markus Huber. “Marina Abramovic and others became famous when geography [of the Balkans] became a subject of public interest. In this way, the art market capitalizes art. It will be the same with Ukraine.”

The “de-oligarchization” of the Vienna Fair can be a good start to a conversation about the deconstruction of Russian culture.