The Monument to Catherine II Will be Dismantled in Odesa. What’s the Best Way to Send the Past to the Cemetery? Daniel Lekhovitser’s Column

The new phase of the war with Russia started the process of Ukrainians revising the memorial policy regarding monuments to Russian and Soviet political and cultural figures. In recent months, Ukrainian society has been arguing about the monument to Empress Catherine II in Odesa — the mayor of the city, Gennady Trukhanov, opposed its dismantling. At the same time, the community pointed to the colonial content of the sculpture. Zaborona’s executive editor Daniel Lekhovitser ponders why the process of historical exorcism began in Ukraine, how it resembles cancel culture, and whether it makes sense to preserve monuments to persona non grata so as not to forget problematic history.

After the Second World War, the phrase “memorial culture” became as common in Germany as today, the term “urban planning” is widespread and democratic. Beyond academia, memorial culture has entered the mainstream. It has become the subject of press coverage, public debate, literature, and the serial industry, and, in more educated circles, a topic of conversation over a pint of beer. If the Cambridge dictionary followed not global trends but the most used words of specific countries, then in post-war Germany, such a word would be Erinnerungskultur — “memorial culture.”

It took the Germans 3-4 generations to develop a system of social agreements about how to treat the National Socialist past: which aspects of it are subject to communicative silence, which are latent oblivion, and which, on the contrary, must be spoken. Since 2014, Ukrainians have been at the beginning of a similar (but different) path. There is a certainty that soon, the phrase “memorial culture” will become an obligatory part of the Ukrainian vocabulary. It is presumptuous to assert that the Ukrainians will be able to master what the Germans have been working on for several decades at an alarming pace. Yes, the world is faster today, but working with the past is old-fashionedly slow and terribly difficult.

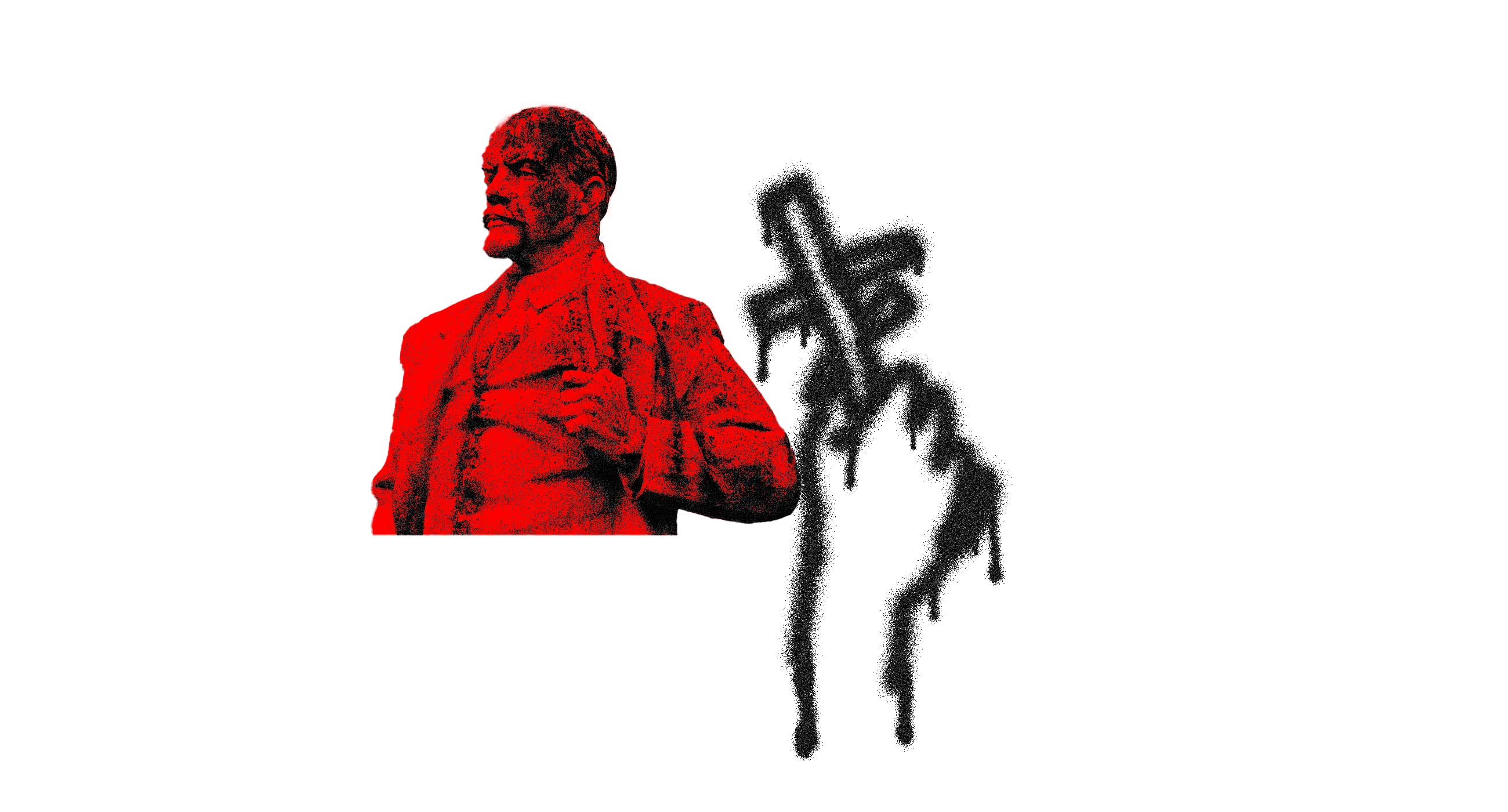

For the last eight years, Ukraine has been experiencing rock fall: dismantling of granite, slate, and bronze. Over the years, cranes have lifted the skins of many Lenins, Dzerzhynskyi, and Soviet soldiers — as if they had held a mock funeral. By the way, the past is so reminiscent of a person who has just died that in Germany, a monument to Lenin was buried in an abandoned Horleben salt mine so that he would not haunt the Berliners like a ghost. In 2022, Empress Catherine II and cultural figures like Pushkin joined this granite political pool. In Ukraine, a process is taking place, which the researcher of memorial culture Aleida Assman calls historical exorcism — a forced attempt to expel the past like a pesky devil. And yet, the past has little resemblance to a demon — a completely different toolkit should be applied to it, not much similar to the Vatican ritual of exorcism. The past planted by the former Russian Empire, no matter how pacifist it sounded during the war, must be reconciled so that it does not haunt the present — because no matter how planted it was, it was a part of unwanted history.

-

Collage: Kateryna Kruglyk / Zaborona

The dismantling of the Catherine II monument in Odesa is fully justified from the anti-colonial and post-communist points of view. Still, it is not the dismantling process that worries, but where the monuments go when they “die” and what (or, more precisely, who) comes into their place. Nietzsche’s phrase that one should carefully approach the past with a sharp knife is significant here. In other words, are we not trying, by dismantling this or that monument, to cancel the period it represents? Isn’t this an attempt to whitewash a tarnished history and then iron it out, full of crinkles and unevenness?

In some ways, historical exorcism can resemble cancel culture — both practices seek to strip the perpetrator of social capital and reputational integrity. However, there is one difference. Cancel culture can be called the modernized practice of being tied to the pole of shame. The object of criticism here does not disappear anywhere — they remain a subject of society’s memory, which allows reputational oppression to continue to be carried out against them. The memorial analog of the cancel culture seems to be more correctly called the culture of prohibition — the prohibition to remember until the memory itself weathers away and turns into oblivion. From the era of the pharaohs, the ancient Greeks, and Romans, the practice of damnatio memoriae spread worldwide — scraping off mentions of the name and destroying busts and sculptures of the guilty ones. But if we are talking about a historical figure whose name is associated with colonialism, war, or repression, wouldn’t it be more appropriate, as the culture of abolition does, to remember these crimes and thereby warn new generations against their repetition? Shame and disgrace, fueling a cancel culture, do not appear to be productive feelings; memorial culture should instead strive for a different set of emotions that a monument with a minus sign would evoke — the desire to prevent the appearance of such a person or event in the future. It requires memory work.

-

Collage: Kateryna Kruglyk / Zaborona

It is important to note that I am not against dismantling itself but simply trying to trace the possible trajectory of the route of the monument to Catherine II. It is customary to believe that the monument, as it were, issues a visa to immortality cast in bronze. In my opinion, the monument is the materiality of the past era, its testimony, and not an exclusive invitation to the club of those who try to avoid oblivion (at least, this is how it is logically viewed from our century). It is clear that the design of the monument and its manufacture cost a lot of money, and until then, it was considered a means of aggrandizement. But if a section of the public now says that the existence of monuments to persona non grata is unacceptable, isn’t the same true of the podcasts and true crime series about serial killers produced at an unprecedented rate today? Such series are needed not only to excite the audience’s imagination but also to understand what kind of darkness was in the skull of a person who killed tens or hundreds of people. In a sense, a monument can and should serve the same purpose. It must be contextualized — add a textual or audio note about Vladimir Lenin’s or Francisco Franco’s crimes.

Probably, its location played a significant role in the dispute about the dismantling of the monument to Catherine II. The monument installed in the center of the city really inspires the idea that this historical figure is fundamental for the self-identification of modern residents of Odesa. Several possible solutions would reduce the monument’s significance but not completely destroy it.

For example, let’s remember the dismantling of the Tallinn monument to the Soviet soldier Alyosha and its relocation to the old cemetery. Such a gesture fulfills three functions: it does not cancel the history of the Soviet occupation of the Baltic states, and at the same time, it reduces the prestige of the monument, which has now been moved to the outskirts of the city. The people of Tallinn say goodbye to the monument, sending it to the symbolic and actual cemetery.

Another farewell to inconvenient monuments took place in Berlin, where a kind of museum of the canceled works in the Spandau fortress. So, in its yard, Lenin, dismantled after the disappearance of East Germany, and Kaiser Friedrich III, who did not live up to the empire’s hopes, live next door. The format of the museum of dismantled monuments seems to be a successful strategy: the museum is not an ethically impeccable institution (it is a product of colonialism, a container of culture and lack of culture if guided by the idea of theft); it preserves the memory of history, even if it is negative.

Historical exorcism is based on the fact that the past must be cast out like a demon. The metaphor of the ghost seems more moderate. You don’t have to fight it — you have to put it to rest and, as is often the case in ghost stories, bury the remains according to all the rules. After all, even murderers and criminals have a tombstone on which the dates of life and death are indicated in addition to their track record.