Architecture researcher Semуn Shirochyn continues a series of materials about cities of energy workers. Due to their youth and the overall homogeneity of buildings, they have never been studied from the point of view of architectural heritage. However, they have special examples of architecture and monumental art, which are worthy of the general public learning about them. We have already talked about the oldest towns near TPSs or HPPs (in particular, Nova Kakhovka), as well as cities built for NPP workers.

The new material is dedicated to Slavutych, the youngest city in Ukraine. It was built after the accident at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant when the Pripyat station built for workers (more about the town — here) was evacuated due to unfitness for living.

After the Chornobyl nuclear power plant accident, the city of Pripyat was evacuated. Still, the work of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant did not stop, and by the end of 1986, the first three power units resumed working. So the USSR authorities faced a non-standard and complex urban planning task: to build a city of nuclear workers in the shortest possible time, not for a new station, but for an already working station.

The territory near the Chornobyl nuclear power plant was in the zone of radioactive damage — therefore, the city had to be built at a safe distance. At the same time, it had to be made just a short distance from the station to make it convenient for employees to get to work.

Initially, the Dnipro coast near the Belarusian border was considered to develop a new city, but due to the complex geology, this idea was abandoned. As a result, the designers stopped at a location 10 kilometers from the banks of the Dnipro. And although this area belongs to the Chernihiv region, the city was subordinated to the Kyiv region, which formed an exclave uncharacteristic of the administrative-territorial system of Ukraine.

Despite the distance of 10 kilometers, the city was named in honor of the Dnipro — Slavutych (the ancient Slavic name of the river). This name has already appeared as a candidate for the name of a new city of energy workers on the Dnipro — in particular, in the 1970s, Energodar could have been called that.

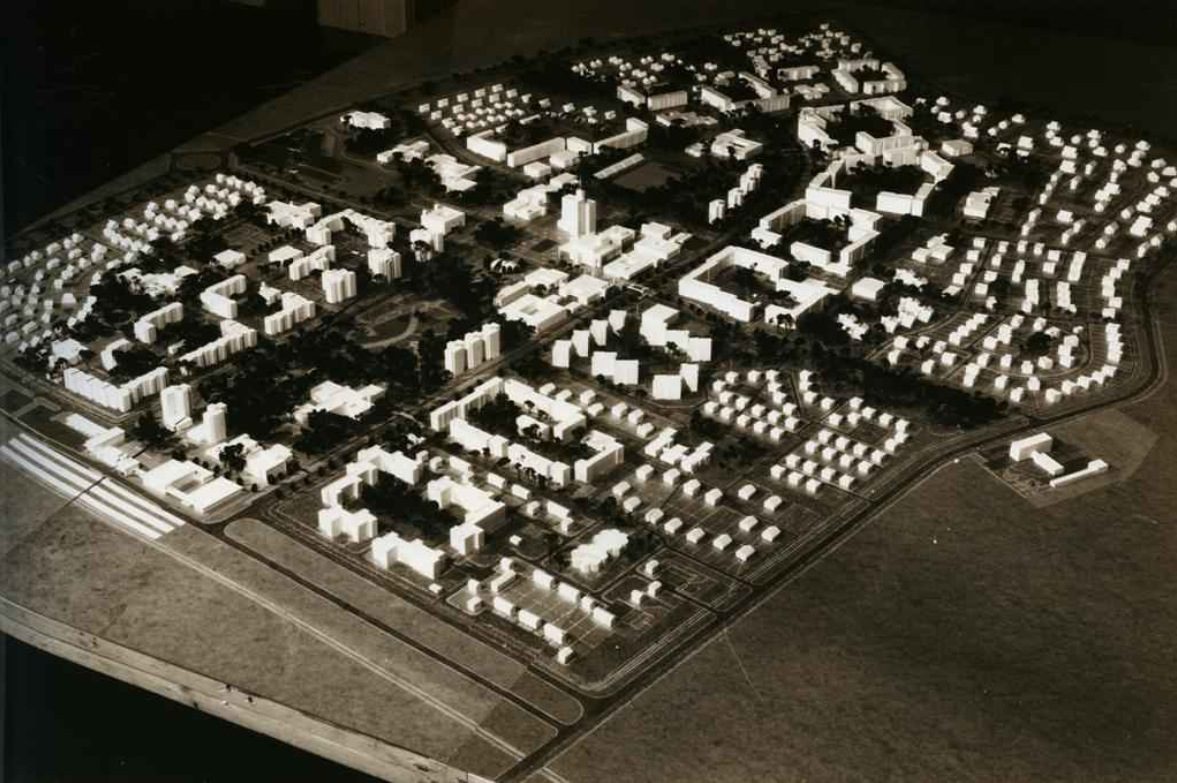

The layout of Slavutych. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

People-centric city

Slavutych significantly differed from previous nuclear power plants, often developed without a master plan. Despite the enormous design speed (it took only 2 months), the city was developed in detail and with great attention to people.

Slavutych was planned as a garden city: public transport was not expected, everything necessary had to be within walking distance, and pedestrians were the center of attention. During the construction, fragments of the coniferous forest, among which the city was built, were preserved — this involved not only the interaction of people with each other but also their interaction with nature.

Since the design was during the Soviet period of perestroika, which brought greater freedom of creativity, the old typical construction methods were combined here with new human-centered ideas. The priority was residents’ comfort, for which the German historian Anna Veronika Wendland called Slavutych “the last urban utopia of the USSR.”

It was facilitated by Slavutych becoming an image project, unlike other nuclear towns. Money was not spared for him — even despite the huge costs associated with the liquidation of the accident at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant. So, here you can see both the shortcomings of Soviet standardization and typification and the advantages of humane urban planning ideas.

Slavutych should have become better than Pripyat since most of the population came from there and suffered the trauma of losing their hometown. Slavutych was supposed to become a better home for them and, at the same time, not remind them of the tragedy.

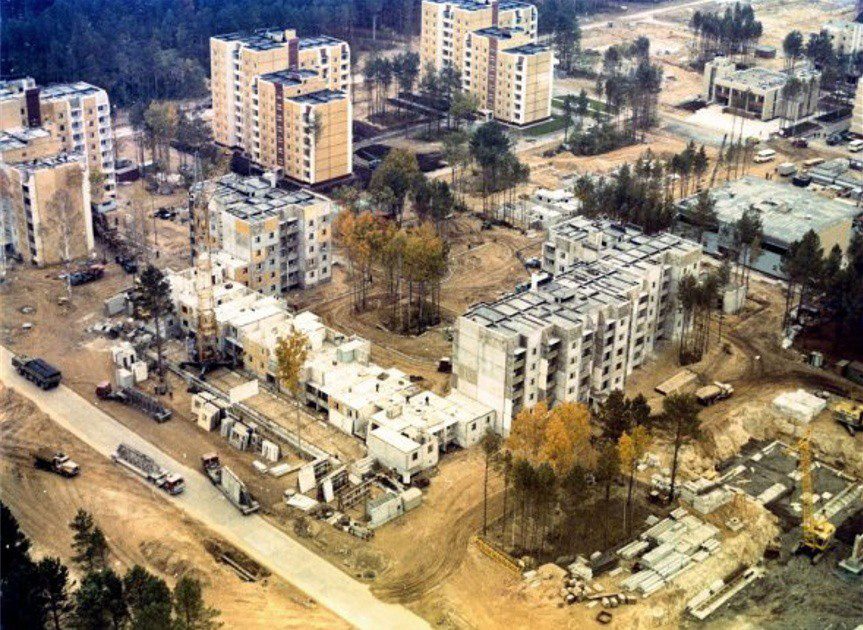

Kyiv block, 1987–1988. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

Riga Block, 1988. Photo courtesy of Semen Shirochyn

City symbols

Slavutych is devoid of both the formality of state symbols characteristic of Soviet cities and the atomic symbolism characteristic of nuclear cities. Unlike Varash, there are no models of atoms or power plants in the city’s public space and city symbols.

Emblem of Slavutych

The heraldry of the city was chosen in 1990 at a competition. A model of the atom symbolized some of the proposed sketches, and some depicted the forest and the Dnipro. Some variants even included the Ukrainian trident. However, the commission chose the version of Trofimov and Kostiantynov: a black bottom, a blue top, and a gold eight-pointed star. It became a new symbol of atomic energy instead of the traditional model of the atom, which subsequently caused associations with the Chornobyl accident.

The eight-pointed star also had another symbolism — the eight republics that built the city. In some competitive versions of the coat of arms, there were also eight stars, lights, flags, flowers, etc. In one of the versions of the winning project, an image of the Archangel Michael was in the upper part of the emblem as a symbol of Slavutych’s affiliation to the Kyiv region.

As a result, the city’s emblem was approved only on December 17, 1999 — two days after the closure of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant. An eight-pointed star, the upper half of Archangel Michael, and the Dnipro waves were there.

Multicultural quarters

To build the city as soon as possible, the committee built the last all-Union building in the USSR. In the Soviet Union, this practice was where promptness, a significant expenditure budget, and concentration of resources were required. In this way, the construction also acquired a political aspect, confirming the thesis of friendship between nations.

Similarly, for example, Tashkent was rebuilt after the 1966 earthquake. Then a “Ukrainian quarter” appeared in the capital of Uzbekistan with slightly modified houses of the Ukrainian typical series. The concept of a “Ukrainian house” is still preserved in the city, which often appears in advertisements to sell apartments.

Up to 35 organizations from eight republics of the USSR participated in the design of Slavutych. Each project organization represented a specific architectural school and had its characteristics — such urban multiculturalism echoed the pluralism of the perestroika era.

Thirteen residential quarters were built in the city: Baku, Belgorod, Vilnius, Dobryninsky, Yerevan, Kyiv, Nevsky (formerly Leningrad), Moscow, Riga, Tallinn, Tbilisi, Chernihiv, and Pechersk. After the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Moscow quarter was renamed Polisky, Bilhorodsky — Dniprovsky, and Nevsky — Desnyansky.

Each block appears as a specific exhibit in the city-wide composition, which can be read as a catalog and visited as a museum exhibition. The city also has several monumental works of art, and the public buildings in the Republican quarters have specificity in design.

The basis of Slavutych’s buildings is five-story buildings made of block sections. They are primarily ascetic, although architects originally planned to enrich them with monumental art. There are also low-rise buildings (2-3 stories) and private buildings with houses for 1-2 families in the quarters. Some have an unheard-of luxury for a Soviet person — their parking lot in a private facility.

Center

The central part of the city is non-residential; all the main institutions of Slavutych are here. Given the priority of pedestrian accessibility, this space inside is entirely dedicated to pedestrians, although it has roads on the edges.

The center has clear functional zoning. In the southern part, there are now a train station and a bus station, as well as a dilapidated bath and laundry plant and an unfinished hotel, which was supposed to be the largest building in the city. A city park with a preserved fragment of the forest stretches further north. The city civic center of Slavutych almost coincides with the geographical one and is arranged as a district of city institutions.

The central square is built up with typical administrative and commercial buildings. There is a post office and a cinema, a children’s art house and an art school, the city council and the Civil Registry Office of the Department of Justice, a museum, and retail premises. All buildings are mostly veneered with white stone, which gives them a united ensemble look.

In the southeastern part of the square, the department store “Dnipro” was built, which was developed according to a typical project, but with an original clock tower. Nearby is the “Minsk” department store, which was financed by Belarus, which, due to the consequences of the accident at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant, did not participate in the construction of Slavutych. Due to the participation of Belarus in a full-scale war against Ukraine in 2022, the department store received a new name, “Desna.”

Department store “Dnipro”. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

A children’s art school was built behind the city council building in the western part of the central square. Its building contrasts with the primarily laconic facades of the center, as it has a structure with tall columns like an ancient Greek Periptera temple.

It was planned to make a high-rise administrative building in its northern part the main dominant feature of the square. But it was impossible to build, and today the “white angel of Slavutych” monument was erected in this place. In addition, the Palace of Culture for 700 people, the city library, the research institute building, and the memorial to the victims of the accident at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant were never built in the center of the city.

Children’s art school. Photo: Maria Petrova

Kyiv block

The largest quarter in the city occupies the southwestern part of residential buildings. A system of pedestrian paths and promenades is crucial in its structure. Near the sports complex, there is even a small pedestrian square with a stage inside the block.

Residential buildings of the block are panel, from 5 to 9 floors. They form the red line of the quarter. The Kyiv block also has the largest (almost a hundred) sector of two-story houses made of silicate bricks.

Київський квартал. Фото: Семен ШирочинКиївський квартал. Фото: Семен Широчин

Kyiv block. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

Caucasian blocks

There are the blocks of the republics of the Caucasus to the southeast of the center. The southernmost of them is Yerevan, built according to the long-standing architectural tradition of Armenia. One of its characteristic features is the use of tuff in cladding, which can also be seen in Slavutych. In addition to the cladding, Armenian architecture can be seen in the semicircular arches of courtyard passages and red roofs. And the five-story houses have loggias typical of the southern cities of Armenia.

Armenian block. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

Traditional monumental art is also present in this block. There is a fountain with a group of sculptures and a stele with a characteristic Armenian ornament. What’s more, even iron fences and lanterns have an Armenian style. But the most unexpected thing in the block is stationary grills with artistic bas-reliefs inside the yards.

Armenian block. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

Five-story buildings in the nearby Baku block have an oriental look: their facades are decorated with stylized ornaments. There are also three-story buildings with ornamented balcony parapets and a geometric frieze of the attic floor. Public buildings faced with travertine are also interesting, with national patterns in the ornament of the cornice. In particular, the “Ainur” shopping center has a characteristic eastern gallery with stairs.

Five-story buildings in the Tbilisi block are decorated with machicolation on cornices and balconies with decorative cast iron. Two-story houses in the block have underground garages.

Baku block. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

Tbilisi block. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

Former Russian quarters

To the north of the Tbilisi quarter, behind the pedestrian alley and the road leading to the city center, is the former Moscow block, represented by five-, seven- and 12-story buildings (the latter are the tallest in the city).

The former Leningrad quarter represents another architectural school. The center of his composition is not the inner part of the block but its border with the former Belgorod quarter — a pedestrian alley along the fountains and the “Bogatyr” physical culture complex with monumental art on the ancient Russian theme. The “Slovyanka” household building and the “Rus” store also attract attention. The public buildings of the cafe and shop are made of red brick and are stylized according to historical decorative elements.

Belgorod block. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

Baltic blocks

The northwestern part of the city is built up by the Baltic states — Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. Despite Soviet standardization, they had their schools determined by climatic features and historical tradition, as well as the proximity of the Scandinavian countries to their schools of design.

Modern architecture and national traditions are balanced in the northernmost Vilnius block: concrete aesthetics are enlivened by the geometric ornaments of the entrance groups. Cafe “Kaunas” was built as a one-story annex to five-story buildings. The private development has 40 houses per family. Their roof is covered with red tiles, typical for Lithuania.

Vilnius block. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

Riga block is located to the south. The Latvian school of architecture, which has a more significant Scandinavian influence, is represented, in particular, by three-story brick buildings with pitched roofs. The lack of high fences around private houses, characteristic of Ukraine, is also reminiscent of Scandinavia.

In the Tallinn quarter, the building is combined with a forest landscape. Laconic five-story buildings are adjacent to the “Old Tallinn” restaurant and a sports complex. But the most interesting architecture here is the single-story private houses with a low roof made of dark varnished wood, which is typical for Scandinavia.

Tallinn block. Photo: Semen Shirochyn

Slavutych today

On the Ukrainian scale, the city is unique in its accessibility. There are no underpasses, fences between the sidewalk and the road, or fenced yards. The city is entirely pedestrian-friendly and people-friendly. It immediately catches the eyes of Kyivans, who feel like they are in Europe here.

Some people even move here to live: utility services are cheaper, household facilities are no worse, and the quality of life is higher. Residents of Slavutych do not need a car — everywhere can be reached on foot. Here is a humane environment and maximum security. Since the city’s founding, there has not been a single murder in it — even during the war, when Slavutych was under Russian occupation for a short time.

Slavutych is a living city. Despite the Chornobyl nuclear power plant’s closure, the Ukrainian authorities launched several projects that allowed residents to stay at work and not leave the city. Slavutych became the only atomic city in Ukraine (apart from the abandoned Pripyat), which is interesting from a tourist point of view. A cultural component is added to the architectural diversity here — the city authorities pay attention to cultural events, film screenings, and festivals.